The Startup Drake Equation

Most startups fail, even when the founders are smart, driven, passionate, capable, and are solving a problem that people really would pay to have solved. Why?

We already explored the primary causes of startup failure and how to avoid them. If you know where you’re going to die, don’t go there.

However, all that notwithstanding, failure remains the most common outcome. Perhaps “why do startups fail” is the wrong question—startups fail by default; we don’t need fancy explanations. The question is: Why do they ever survive?

And: Why specifically are they default-dead? Is there something we can learn from that?

The Drake explanation

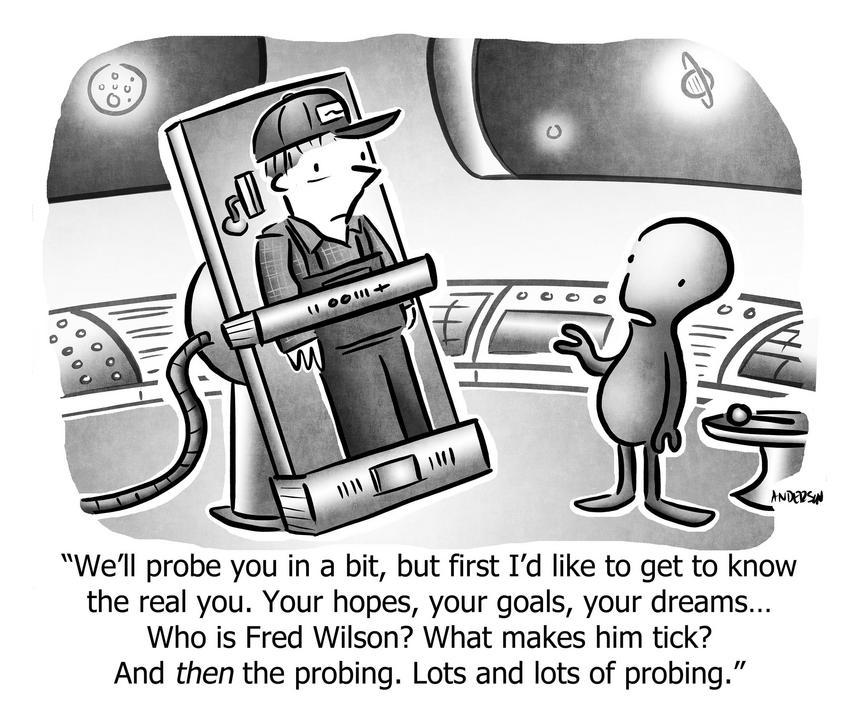

Frank Drake created his eponymous Equation in 1961 to guide discussions at the first meeting of SETI (the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Life). It became a famous a way of estimating how many alien civilizations we should expect to see in the night sky:

Frank Drake, Cornell, 2017

In English: There are billions of stars , some fraction of which have planets

, some fraction of which are habitable

, on which life sometimes forms

, and sometimes becomes intelligent

, and transmits detectable signals into space

, and have been doing so for long enough for us to see it

. So that’s how many aliens civilizations we should see

.

Or in modern Marketing language:

The galaxy produces many warm leads, but every step of the conversion funnel is brutally leaky, so it’s hard to convert to a sale.

Of course the most salient fact about detecting alien civilizations is: We haven’t detected any alien civilizations. Even though our telescopes provide that the first few values of the Drake Equation are astronomically large. So that means one or perhaps all of those conversion steps are vanishingly improbable.

Startups feel like this too. Countless side projects are started each day, some fraction of which are intended to become money-making endeavors. While the success rate isn’t as low as alien civilizations apparently are, perhaps 999 out of 1000 drop off the chain of probabilities—failing to create a venture where the owner quits their day job and brags to outwardly-supportive-but-inwardly-jealous Twitter “followers” about achieving Product/Market Fit.

Startups face a chain of risks, or as I like to say, a chain of “ands”—many things all have to go right. Of course “all things” rarely go right simultaneously; this is why startups typically fail.

The Startup Drake Equation

Here are just some of the factors in the Startup Drake Equation, the failure of any one of which is terminal:

- Product that people (really!) want to pay for

- Able to grab those people’s attention amidst the noisy internet

- Pricing that those people will accept (and substantially greater than costs)

- Competitive and distinctive enough to be chosen

- Able to build the product as promised by the home page

- Sustained value-delivery months and years later, so customers stay and keep paying

- Able to fund the venture, either through early profits or fundraising

- Able to work well with co-founders (or able execute everything alone)

- A repeatable and profitable customer acquisition process

- Able to attract and retain talent

- Able to psychologically handle many years of deep effort, stress, and pain

- Get lucky (capture good luck, dodge bad luck)

It’s easy to find examples of failures due to each factor. The non-technical founder who unsuccessfully outsources the product to a consultant (fails “can build it”). The technical founder who builds forever without validating with customers (fails “product that people want to pay for” and “able to get attention”). The tried-but-not-always-true “I had the problem myself, so I built it” origin story, where not enough other people have the problem and the budget and desire to have it solved. Or it was too hard to push through the pain of iteration and pivoting, and anyway the day job pays well, and there’s a two-year-old at home, so after six months the founder gives up.

The insights of this model are:

- The failure of just one element is fatal, so we should spend more time identifying and then addressing the biggest areas of risk.

- We can analyze and decide strategy in terms of “reducing risk” or “increasing chances” rather than “best ideas” or “unique strategy” or “changing the world”.

What follows is how to use these insights to increase your chance of success.

Completely crush a few areas to overcome risks and weaknesses

No organization is low-risk in all areas. But perhaps some areas can be 100%, or effectively “greater than 100%,” which then makes up for other deficiencies.

For example, a top-1% engineer might satisfy the question of whether we can build it, but “greater” is wrapping a strategy around the founder of a successful open source project backed by a burgeoning community, which then becomes a unique competitive and marketing advantage, which overcomes deficiencies like not having unique features in the product or not having special skills in advertising. Or, teaming up with a successful influencer who already has distribution, is worth giving up 50% of your equity, because it far more than doubles the likelihood of success. Or, being a renowned expert in some market decreases market risk, both because it’s a marketing advantage and because you have insights that others lack.1 Whereas if you’re entering a market you know nothing about, your education might prove fatal.

1 Although be wary; your experience could be blinding you.

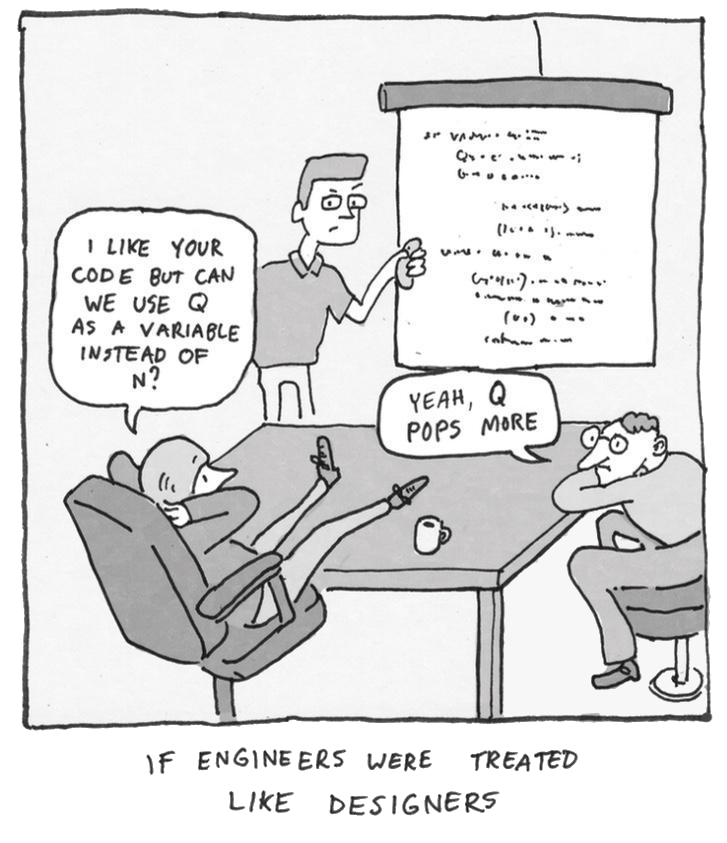

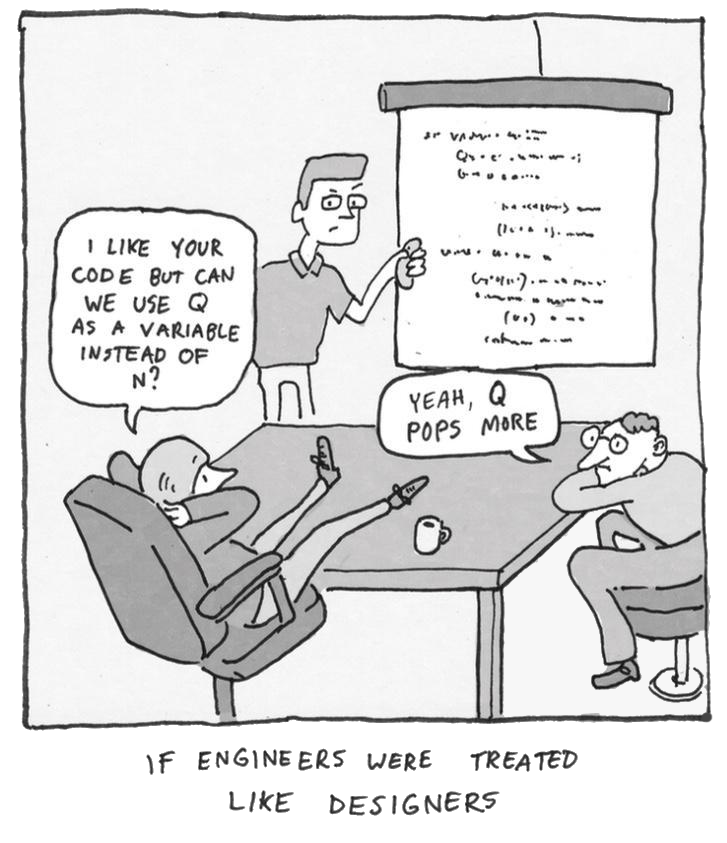

I give several examples of this in The Important Thing. You gain both focus and a higher probability of success when you have a singular winning attribute, even when you’re terrible at everything else. Singular focus and differentiation can overcome deficiencies elsewhere in the Startup Drake Equation:

Even better than “different,” is to be extreme in that difference. Not just a minimal UI, but so minimal it works on the command-line. Not just great design, but so remarkable people buy it only for that, and it’s written up on designer’s blogs. Not just a new algorithm that solves an old problem, but one that uncovers new things that no one else does, even at the expense of missing things that others catch. You can’t do this for all aspects of your product and business—indeed, even a single one is already powerful—but extremity is how you maximize the power of the few things that make you special.

Select the easiest product/market/customer

We typically think about “target market” with a success-oriented question like: “Who would be delighted by this product?” But a risk-oriented version of this question is sometimes easier to answer:

What would be the easiest customer segment for us to target?

Here “easy” doesn’t only mean that you can do it, or that it’s fun, but also that it is profitable. As a negative example, indie hackers2 enjoy selling to their peer indie hackers, but indie hackers have no money and usually go out of business in less than a year, so that’s a terrible segment. Instead, stable small businesses like dentist offices have large budgets, rarely change software, and last for decades; this is a better market.3 Large, growing markets are better still, because “large” means are many niches in which to get started, many adjacencies to expand into later, and incumbents are fighting over new customers, not focussed on new entrants who aren’t big enough yet to be worrisome. Big, growing markets are “easy” in this sense.

2 Found mainly on Twitter but increasingly on Bluesky, the quintessential “indie hacker” is a solo founder, who never wants to hire even one employee, who can build software without assistance, who values freedom, flexibility, and autonomy over maximizing money or traditional prestige. They therefore build simple (but hopefully delightful) products, at low prices, designed to be profitable without scaling.

3 Better for sustainable revenue, but difficult to sell, as dentists are hard to get on the phone, and aren’t usually in the market for new software. Nothing is easy!

Koan #44

The bootstrappers

As an army of 10,000

battles another army of 10,000…

…three bandits sneak into camp,

stealing enough to feed themselves for years.

They are ignored; retaliation is low-ROI.

The other key factor is in the phrase “for us”. Enterprise customers might be willing to pay gobs of money for a decade, but a new company run by a single person will not be able to deliver the complex software, integrations, governance protocols, and professional services that even one Enterprise customer demands, therefore “Enterprise” would be a risky segment choice for them.

You must select low-risk markets that are easy for you to address. You could pick a different word than “easy”—lucrative, growing, profitable—but I like “easy” because it keeps things personal. Do you think it will be easy? If so, you’re wrong—it will be harder than you think, but still possible. Whereas if you already think it will be difficult, it’s also worse than you fear: impossible.

Founding team

When a co-founder is a top-1% engineer, execution risk goes close to zero.4 When a co-founder is a top-1% growth marketer, and if the market exists, getting-attention risk goes to zero.

4 Except in AI, where the normal rules are different, and the world’s best engineers often in fact aren’t making it work.

This is one reason why investors like two founders—“one to build it, one to get rid of it” as we used to say at ITWatchDogs. It’s not just “getting twice the work done,” and not just “someone to commiserate with,” but rather it’s because you might dramatically improve two different variables in the Startup Drake equation. (Two technical co-founders is far less interesting.)

Design out weaknesses

You have weaknesses, which creates risk across the Startup Drake equation. But, you can make choices that slalom around most of your weaknesses, making them irrelevant, rather than forcing you to do the impossible: Become great (or even good-enough) at seven different things.

If you’re creating a startup on the side, while you hold a day job and a two-year-old, then you should serve an audience who doesn’t want tech support, or at least is fine with a 48-hour response-time. That might have implications on how complex the product is, how intuitively it is designed, what customers expect of it, and its price. Rather than seeing those as negative constraints, instead realize that this is a superior strategy and product, because it avoids a weakness (amount and consistency of time-available). Indeed, besides solving for the weakness, there are benefits: Your profit margin is higher (because you don’t have support costs) and you can everywhere in the world (because neither language nor timezones are a barrier) and it will be delightful to use (so the only communication is asynchronous praise on Reddit). This can even be done at scale (GMail, Facebook, Twitter, most hardware products). Suddenly a negative “constraint” looks like an insightful advantage.

Or if you’re a terrible designer like me, it would be high-risk to make a product that must appeal to designers or marketing agencies, i.e. people who value and appreciate great design. You’ll do just fine selling to infrastructure engineers or backend Enterprise systems managers.

Or if you’re terrible at marketing, you could create a collaborative product where people have to invite other people in order to use it. While that mechanism is difficult to get started, it means even poor marketing can result in a growing, healthy company. (It’s funny that a “viral” company is also “healthy.”)

Or if you cannot write code, but you are good at selling yourself and solving a class of valuable problems, you could avoid the world of software (whether as-a-service or not), instead creating a “productized service,” in which you sell services, but fulfill that service at low internal cost (and therefore high profit) thanks to your “secret sauce” internal workflows, spreadsheets, and no-code software, which only has to be good enough for your own employees to use.

By acknowledging your weaknesses as fervently as you’re proud about your strengths, you can increase the chance of success by avoiding them, and embracing the knock-on implications.

I cover this in detail in my article on Pivot Points.

Play asymmetric games

As the old joke goes: “The probability of anything is 50%: Either it happens, or it doesn’t.”

In truth the probability of success is typically unknown—the variables in the Startup Drake Equation don’t have clear values. Although that means there will be failures, it also suggests there will be some successes. If the positive magnitude of the few successes exceed the negative magnitude of the failures, we are a success overall.

After all, in most startups, most things are mostly a disaster most of the time. New people joining the company often say, “Wow, I can’t believe you’re doing ______ and yet you’re still in business!” They aren’t wrong; they’re unwittingly proving that some things can be so powerfully positive, that it overwhelms deficiencies.

Many examples of this appear in the “Asymmetric” section of What makes a strategy great. It’s summarized best by Jeff Bezos, who led a company that never stopped taking asymmetric bets:

“I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon.com. Literally.

But a few big successes compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work.”

—Jeff Bezos, The Guardian, 2014

On a smaller scale, there are marketing efforts with a fixed cost, but also a fixed maximum upside, like advertisement where you pay whether or not someone signs up. Or there are marketing efforts with a fixed cost, that could generate new customers for years to come, as with reputation (social media, community forums) or media (successful SEO).

Or there are markets where there are many different ways to win, many niches to try, many routes to customers, many ways to expand from a successful foothold into a wider space, and markets which are stagnant, perhaps shrinking, where every sale is a hard-scrabble against desperate yet monied incumbents.

Pick games where the downside is 1x but the upside potential is 10x or 100x. Then if the realized benefit is “only” 3x, the game is still a success, and hopefully makes up for other weaknesses.

Attack the high-risk areas first

With complex projects, the Risk-First Heuristic tells us to tackle the high-risk things first.

If you start with low-risk tasks you’ll surely succeed, but the high-risk tasks remain unresolved, and remain high-risk. Nine months later, when you finally tackle the high-risk areas, you might discover the entire venture is unworkable. Even if not fatal, new insights means rework, which indicates you’ve wasted time. It’s smarter to address the risky things first, learn from them, change because of them, and complete the rest of the project informed by them.

The Startup Drake Equation lists potential risk areas. Even after designing our product, market, and strategy to circumvent or remove risks, some high-risk areas will remain. Circle those, and address them first.

So if we’re incorporating AI into the product, make sure that actually works first, in real life, because usually it doesn’t5 (at least not as of this writing, as thousands of self-styled “AI Startups” have discovered). Or if we’re unsure what potential customers would actually pay for (as often they have a problem but don’t want to pay to solve it), we should find that out before writing code. Or if we’ve never marketed a new product before, we should make advertisements and landing pages that lead to a waiting list, to make sure we can garner attention before building something that no one will ever see. Or if we’ve never developed a reputation that enables us to talk to customers, we should do things to create those conversations.

5 As an executive once quipped to me twenty years ago, explaining why a new product line had failed: It was a platform portability problem—we couldn’t port it from PowerPoint to Java.

All startups are risky, and even with this model in hand, most startups will still fail.

But, by clearly articulating the risks, reducing some risks through the founding team and selecting the market and product that is right for us, solving one or two so well that they overwhelm other risks, constructing a strategy that designs around things that would otherwise be weaknesses, and attacking the remaining high-risk areas first, you can dramatically improve the chance of success.

Those aliens are out there! Maybe you’re one of them.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/startup-drake-equation/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF