Product/Market Fit (PMF): Experience & Data

Every day people debate how to define “Product/Market Fit.”

It’s best to start with the subjective experience, because there is no doubt when you have it. (If you’re not sure whether you have Product/Market Fit, you don’t.)

If every day it’s a struggle to get customers, it’s not working yet.

If every day it’s a struggle to keep up with demand, it’s working.

It is a momentum change from “push” to “pull”—a change from fighting for each customer, one at a time, to a flood of signups that you can’t even explain. It’s a change from “how do we get more customers” to “how do we handle the influx of demand?”

It’s working. Something clicked, like a final puzzle piece snapping into place, a “fit,” and suddenly the floodgates are open.

It’s not all good. The avalanche of customer complaints outstrip your ability to deliver bug fixes and simple enhancements. You feel behind in every department simultaneously; you can’t keep up with the work no matter how “productive” you are. You obviously should hire someone—and this new revenue means you can afford it—but who? Someone just like you, because you can manage them, or someone who complements you, so you can deal with the burgeoning scale? Does it even matter—you don’t have time to interview.

It’s the proverbial “good problem to have,” but it doesn’t feel good in the moment, with a crushing workload and unhappy new customers, and your brand slipping away (“I heard they were good but it took them a day to answer my support question” says the public review). Although of course it is the best problem to have.

You might think all this doesn’t matter—you’re just running your company; who cares how some article defines a term like “Product/Market Fit?” But it does matter, because it determines whether the company is sustainable, and fundamentally changes how you operate each day, how you plan for the future, whether and who you need to hire, and what you need to build, and whether you’re going to start tackling scale.

(P.S. How do you go from idea to this state? This is my PMF system that I used to build a unicorn.)

What does Product/Market Fit look like numerically?

In my experience building several companies myself and angel-investing in dozens of others (with a wide range of outcomes), I define Product/Market Fit as all of the following:

- Easy growth (pull, not push): Growth rate suddenly spikes up, and sustains at the new rate. You often don’t know why.

- High retention: Cancellation under 3%/mo (for B2B) or 5%/mo (for B2C), because if customers are leaving in droves, you are not a “fit.”

- Critical mass: At least $20,000/mo in revenue or increasing WAU’s by at least 200/mo. Everyone can grow 1000% month-of-month when the baseline is 7 customers; the fact that you have only 7 customers means there’s not yet evidence of “fit.”1

1 What if you have a single huge customer? Congratulations, lots of people would love to have a huge customer; great start. That demonstrates you have fit for a single customer, but not for a market; that’s consulting, not product.

What follows are the data to back up this definition, that also matches the lived experience that is the essence of hitting Product/Market Fit: in which life will never be the same again.

The characteristic growth curve of “Product/Market Fit”

Bootstrapped products

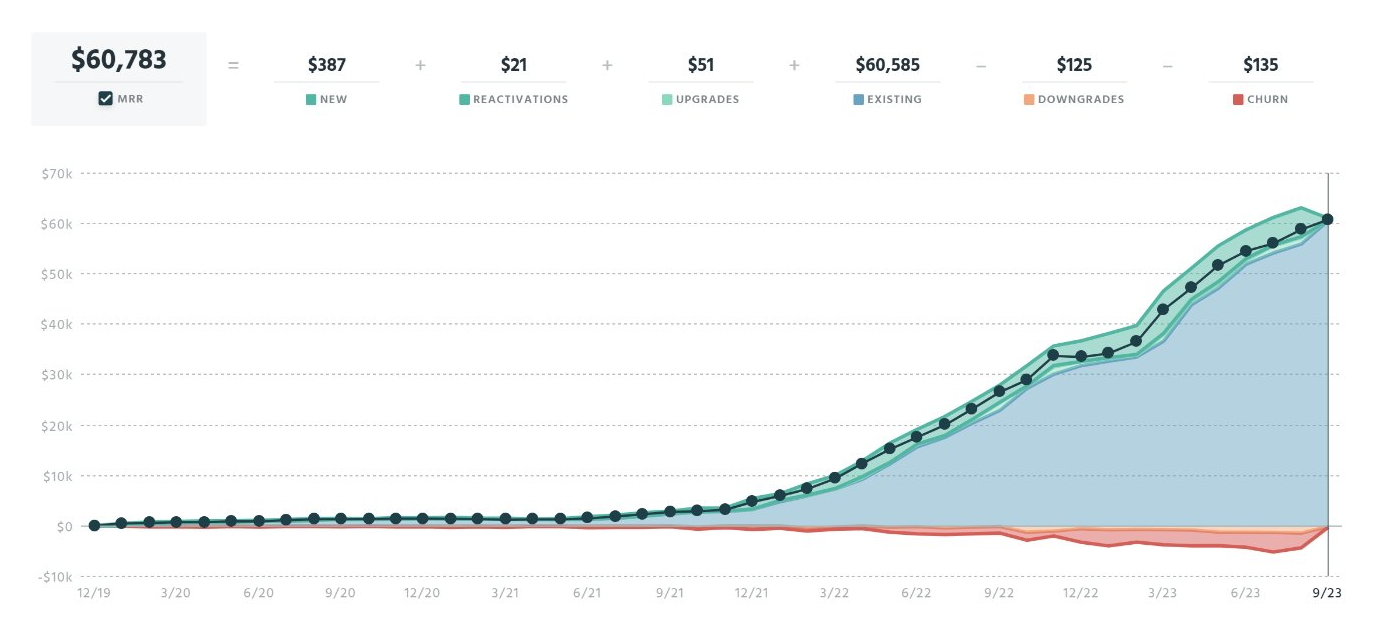

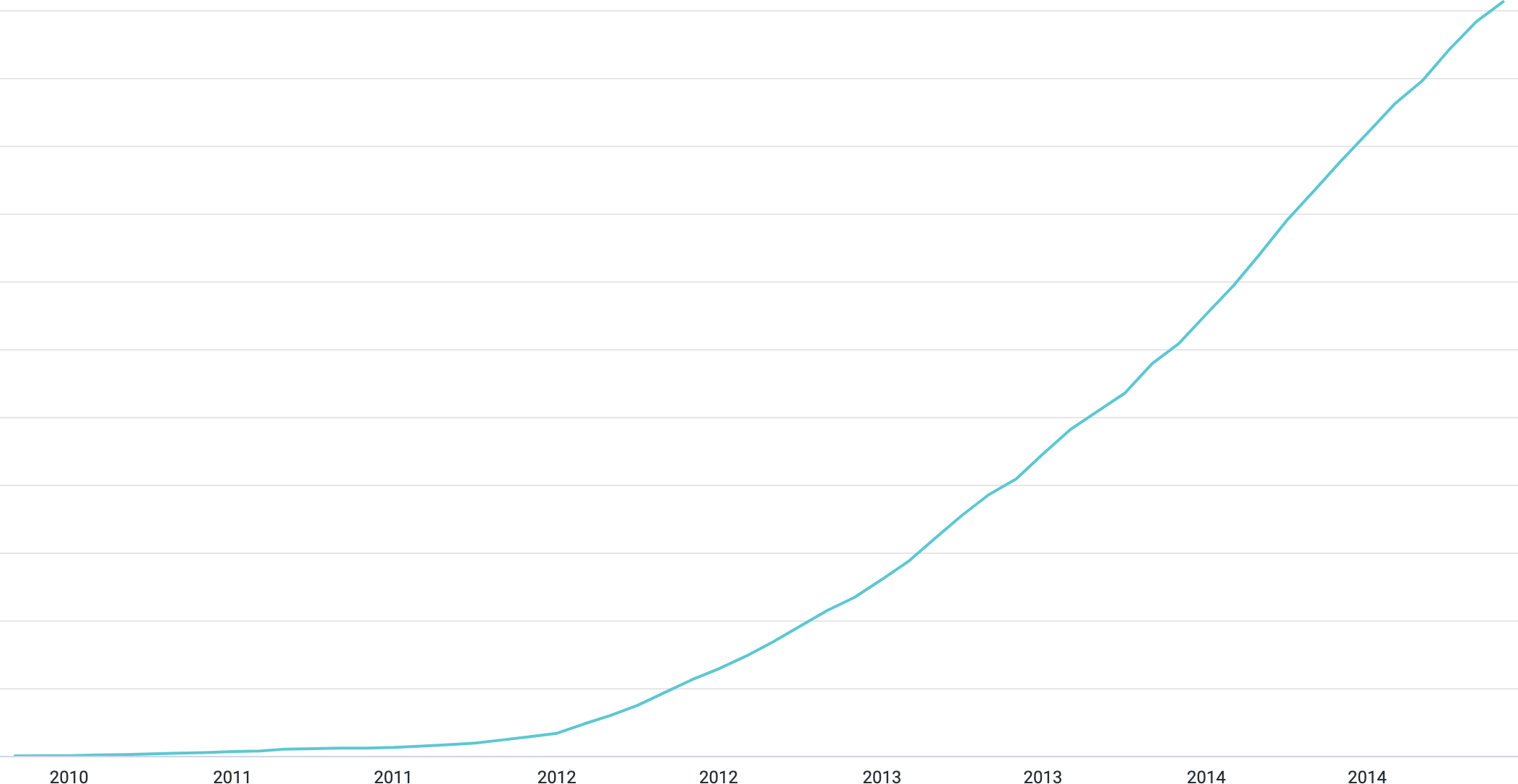

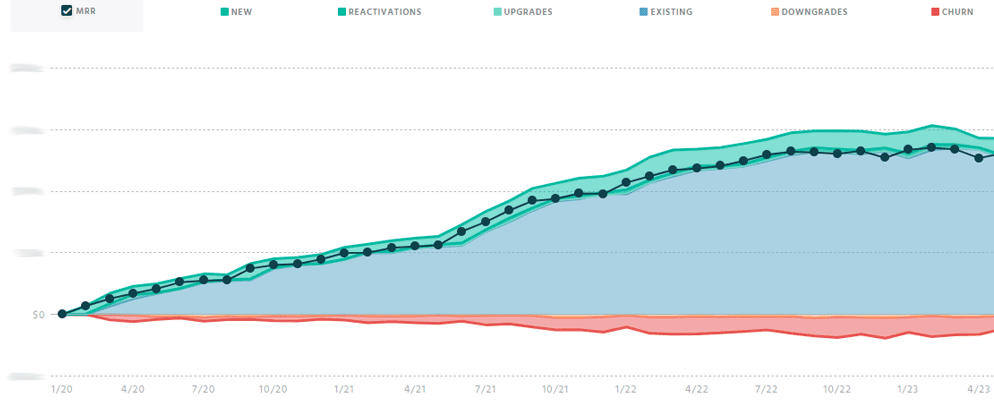

When you see growth charts like Pallyy’s, you can see the exact moment when Product/Market Fit was reached:

Figure 1: Pallyy’s four-year MRR

Successful startups often have a growth curve like Pallyy’s: Revenue growing linearly, slowly, often for about two years, then in a moment—Product/Market Fit—when it suddenly turns upward, and continues growing at that new trajectory.

The new growth is still linear, but dramatically faster. In particular, it is not exponential, though that’s the word people frequently use (this universal fallacy is explained here).

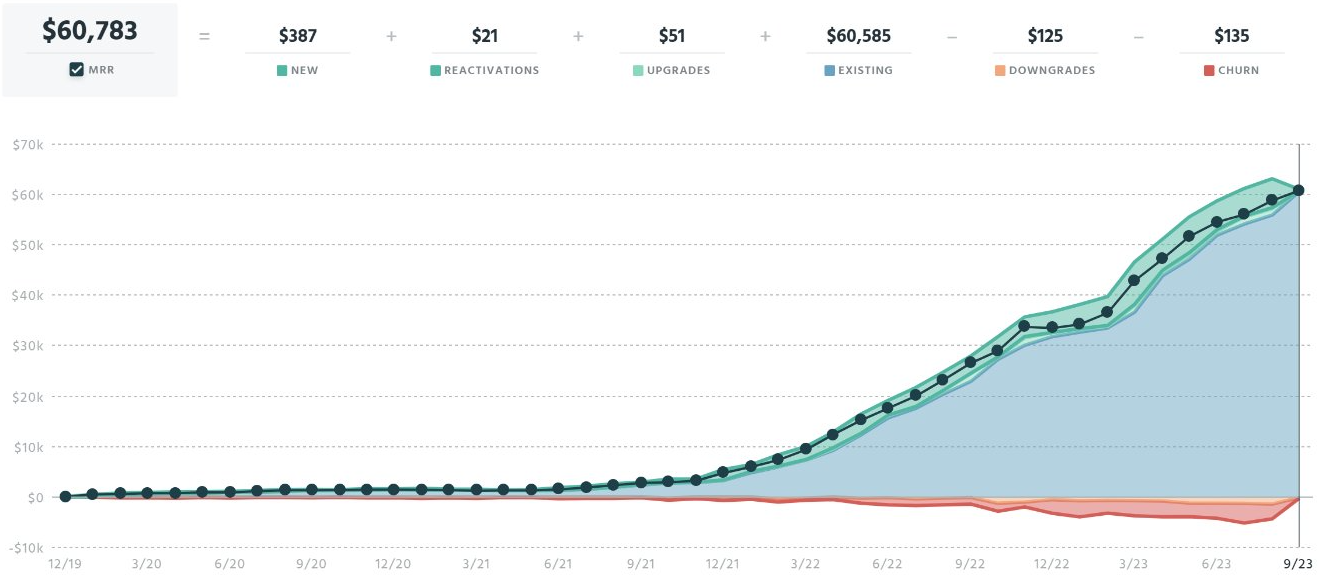

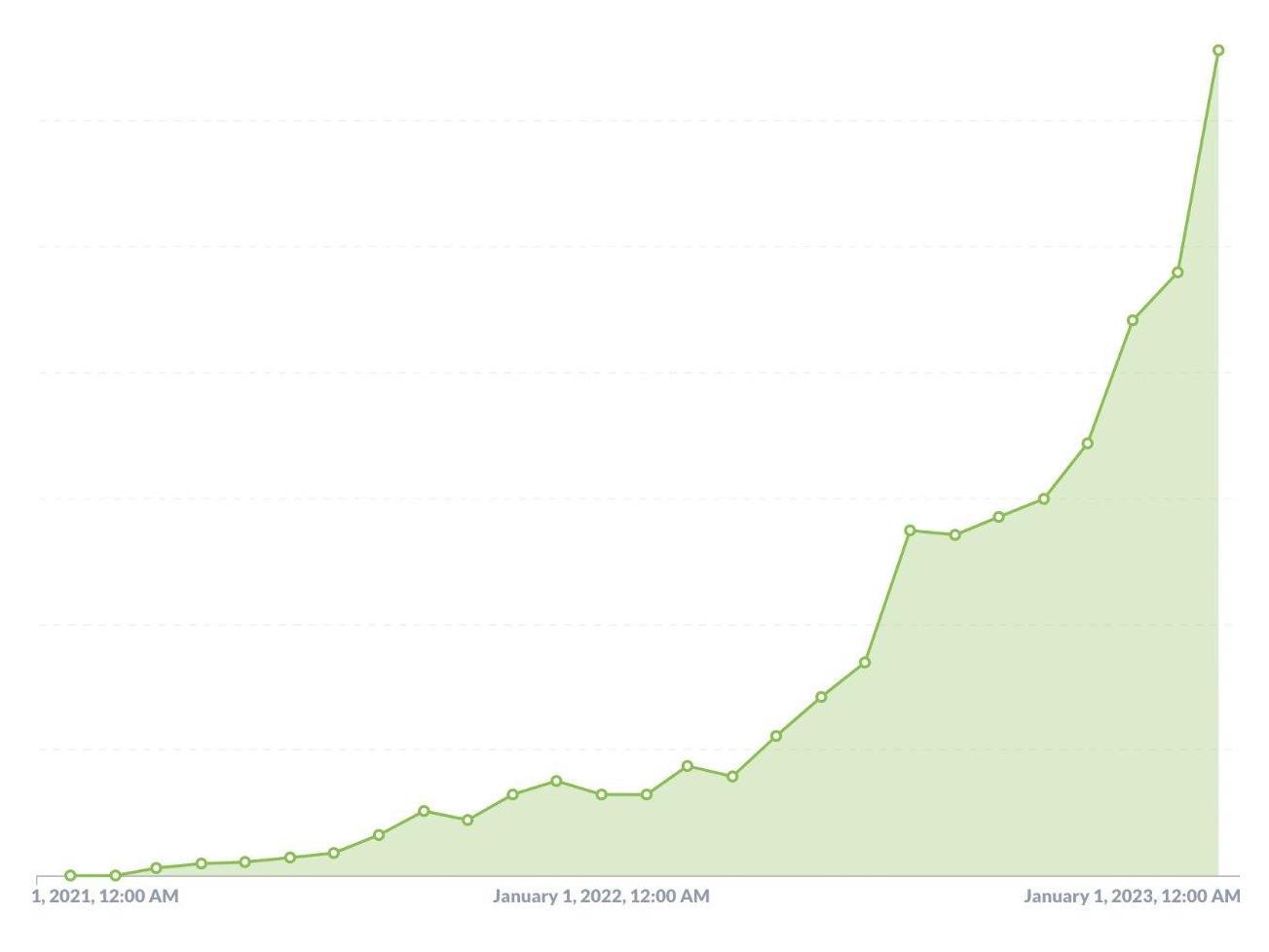

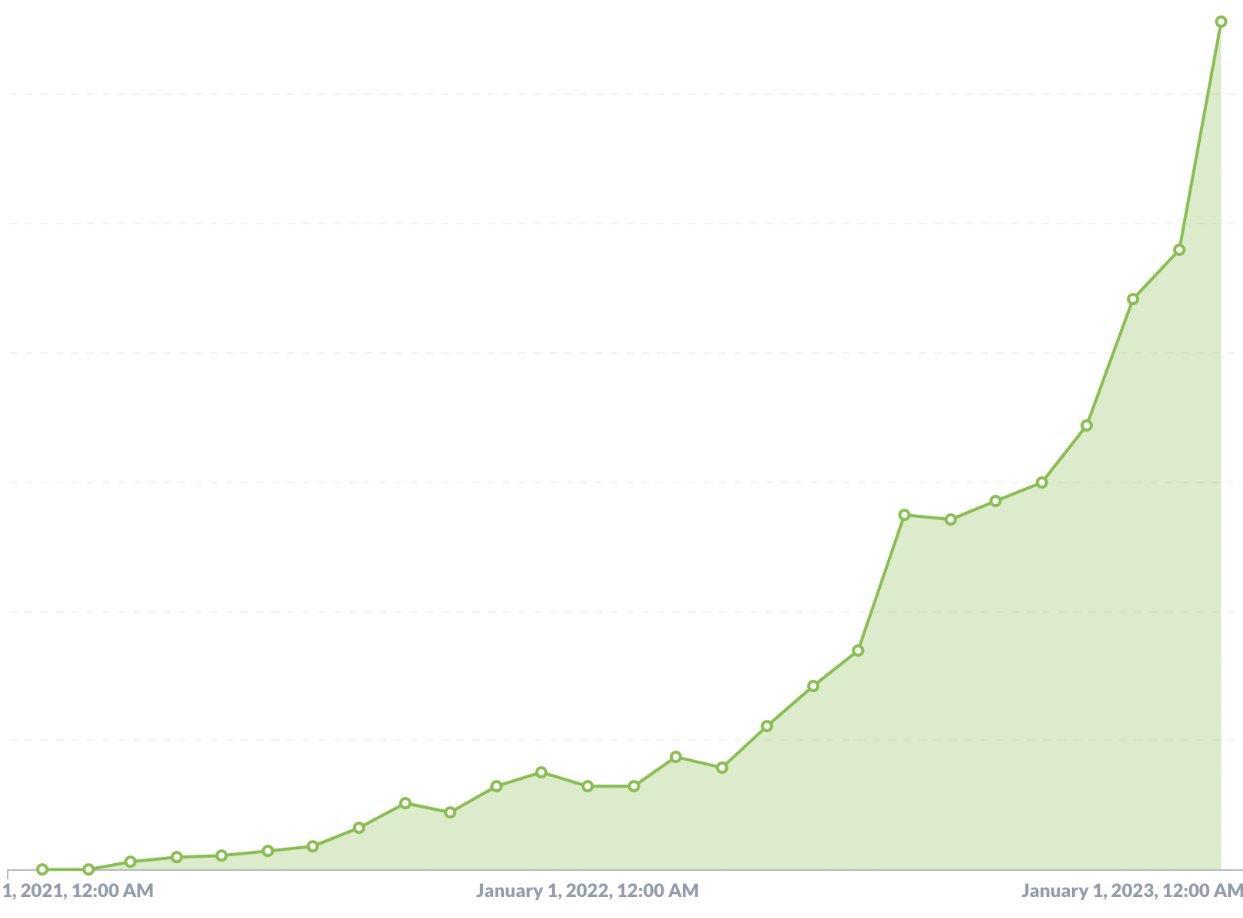

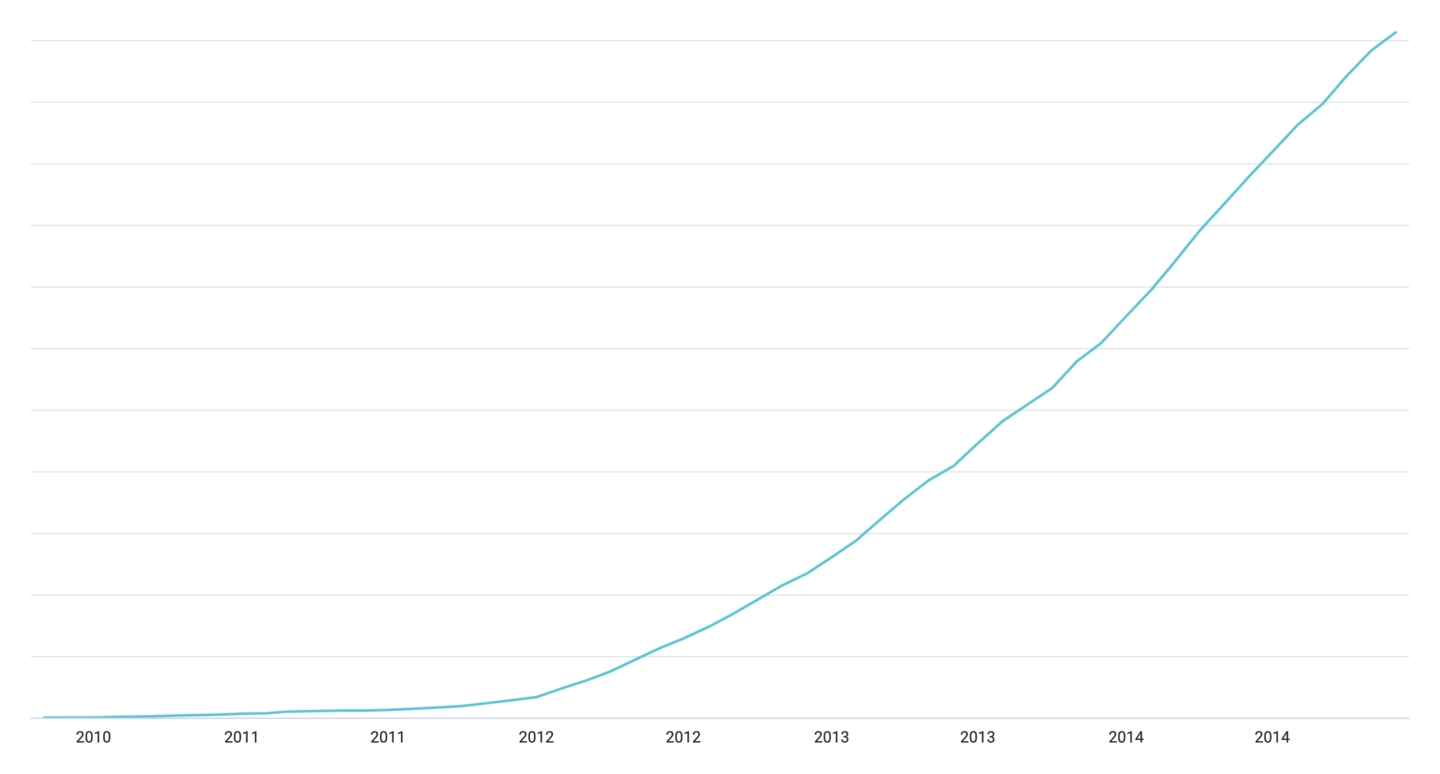

ConvertKit was similar, bumping along for two years before growing quickly but linearly, just like Pallyy:

Figure 2: ConvertKit’s early MRR growth

And then that growth continued linearly, not “exponentially” as many pundits like to say:

Figure 3: ConvertKit’s scale-up MRR growth

You can see the sudden change between “every sale is a struggle” and “the orders just won’t stop coming in.”

ConvertKit founder Nathan Barry famously tells the story of how he personally reached out one by one to his ideal target customers, manually onboarding them to not only get the sale but to get the testimonial.2 It’s a brilliant playbook that others would be wise to copy. It’s also what it means to hard-scrabble for customers, and it’s really obvious when the forces flipping from having to scratch and claw for every dollar of revenue, to the company running away from him.

2 I was one of them; perhaps you’re reading this article because of an email from my newsletter, which is still on ConvertKit.

VC-funded products

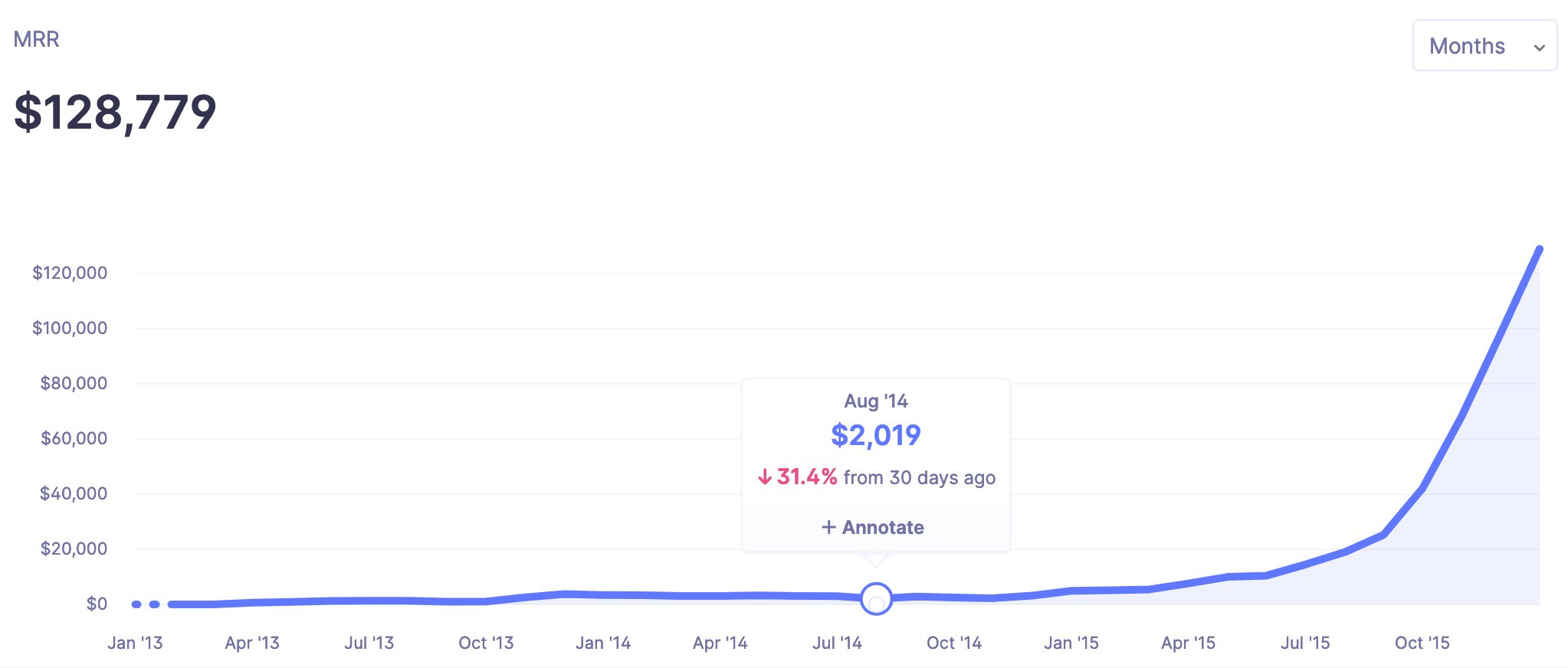

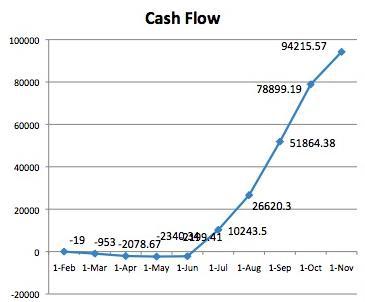

The preceding companies were bootstrapped, but the pattern is the same in the world of venture, because Product/Market Fit is about products and markets and customers and fits, not about funding models. My company WP Engine started 15 years ago self-funded but two years later became VC-funded, eventually raising more than $300M, experiencing hyper-growth3 for a decade, yet it exhibits the same two-year slow-growth preamble to high-growth, and both linear:

3 Often defined as 2T3D, i.e. in successive years after attaining $1M in annual revenue, the company’s revenue triples, triples, doubles, doubles, and doubles, thereby getting close to $100M five years later; WP Engine did that and more, starting with 5x.

Figure 4: WP Engine’s early growth curve

You can’t tell from the chart when we first raised money (it wasn’t January of 2012), nor subsequent rounds, nor the size of the rounds. The shape of growth transcends all of it.

I distinctly remember when we flipped to “Product/Market Fit.” Only five of us, completely sustainable, and suddenly everything changed. We fell behind on our stellar tech support; one of the dangers of bragging about how “the founder does Zendesk tickets” is that process doesn’t scale. We couldn’t keep up with our free white-glove site-migration service for new customers. And then, completely behind on all work, trying to stand up new servers and answer phone calls, knowing we needed to hire, we got even more behind because hiring takes time—finding candidates, interviewing, not wanting to hire the wrong person just because we’re moving fast, and even after we hired, there’s no documentation or training, so we’re just working side by side, hoping folks learn by osmosis, while the team gets even further behind. And customers were complaining on Twitter that our service is going downhill—and worst of all, they were right. They blamed it on us raising money; what they didn’t know is we hadn’t spent a dollar of it yet; in fact our error was not spending the money on hiring ahead of need, to blunt the impact of a growth increase.

We did get back on top of it later in the year, and we’ve won all sorts of awards for our service, maintaining 98% CSAT to this day, because that’s who we are. But that’s not what it felt like in 2012.

The same thing happens to the “cool kids” companies in Y-Combinator:

Figure 5: Anonymous YC company growth chart from YC co-founder Paul Graham

This isn’t a new phenomenon, nor a “SaaS” phenomenon. Peldi Guilizzoni famously shared his (one-time!) revenue for Balsamiq Mockups back in 2008:

Figure 6: Balsamiq Markups one-time (not SaaS!) revenue, 2008

Second products

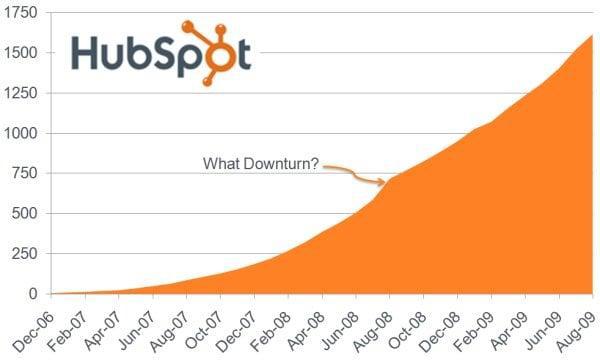

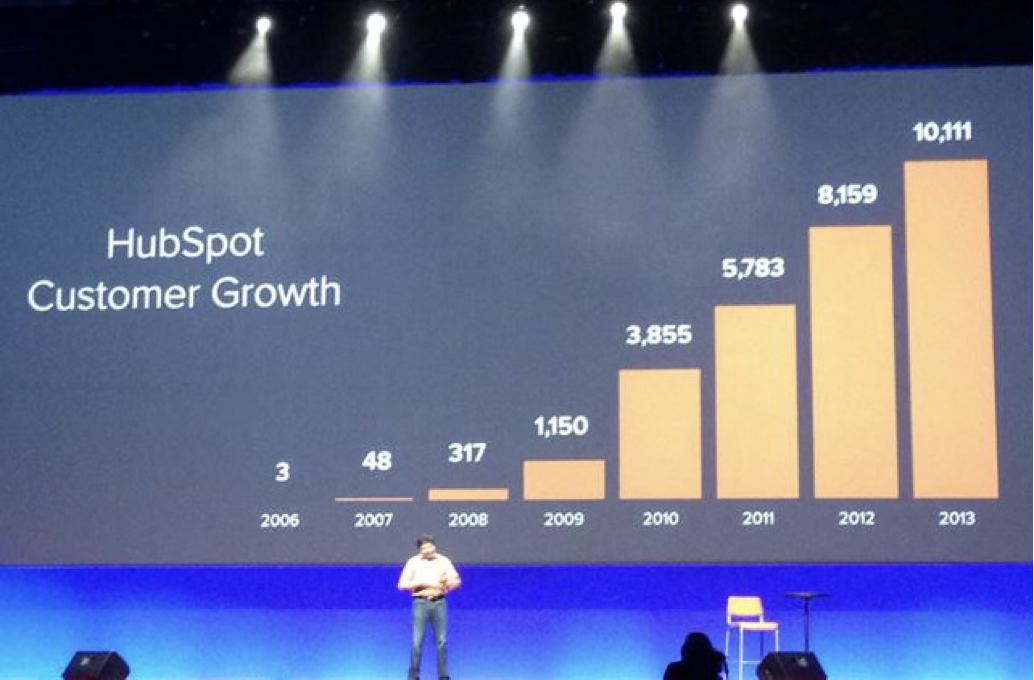

HubSpot is a hyper-growth VC-funded company, now public. Early on, you can see the linear behavior, fairly consistent even through the 2008 recession, as co-founder Dharmesh Shah indicates on a chart from his personal blog:

Figure 7: HubSpot’s early growth curve

And for five years after that point:

Figure 8: HubSpot’s founder Dharmesh Shah showing their slow linear growth rate for three years, then fast for five.

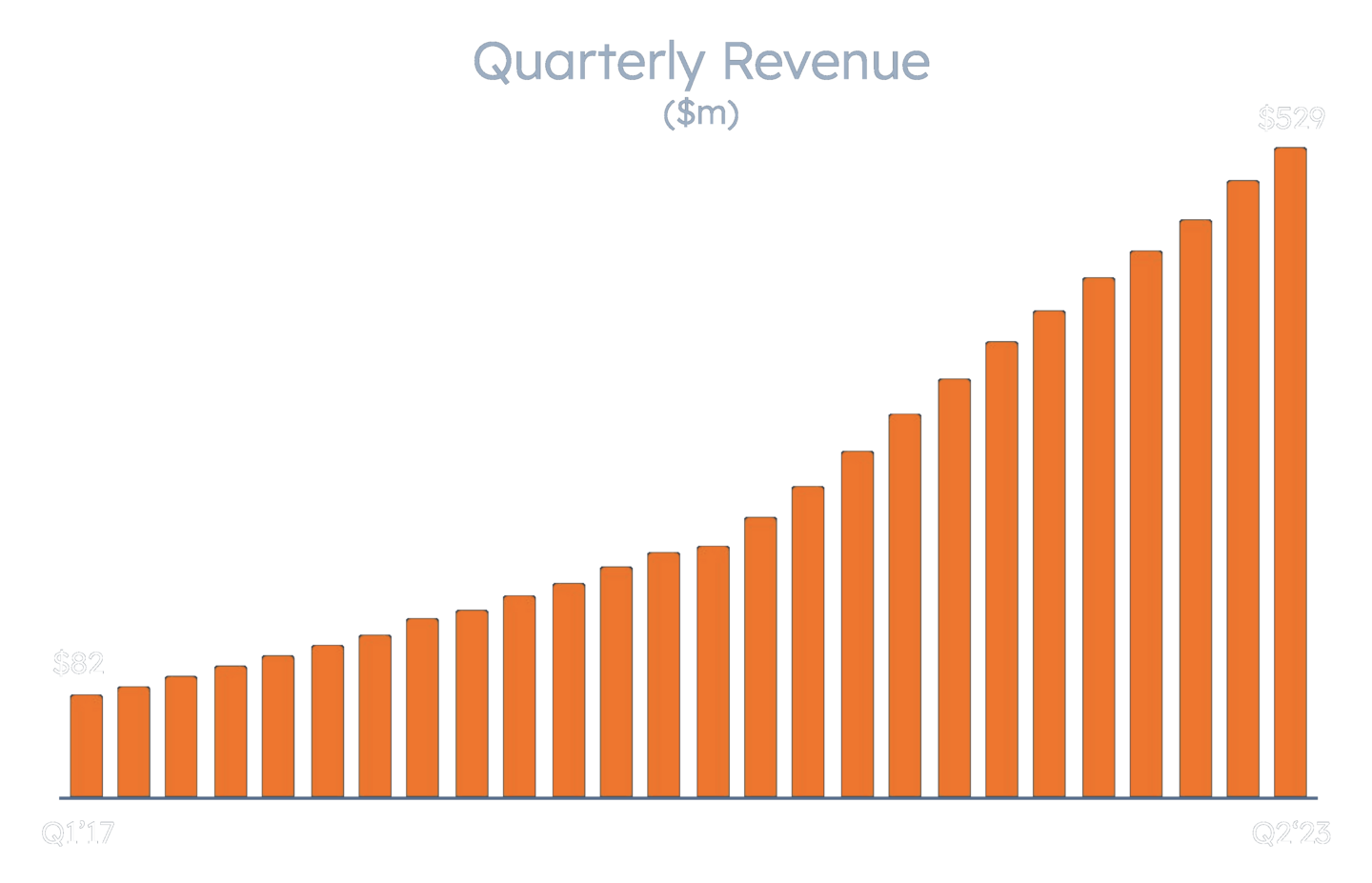

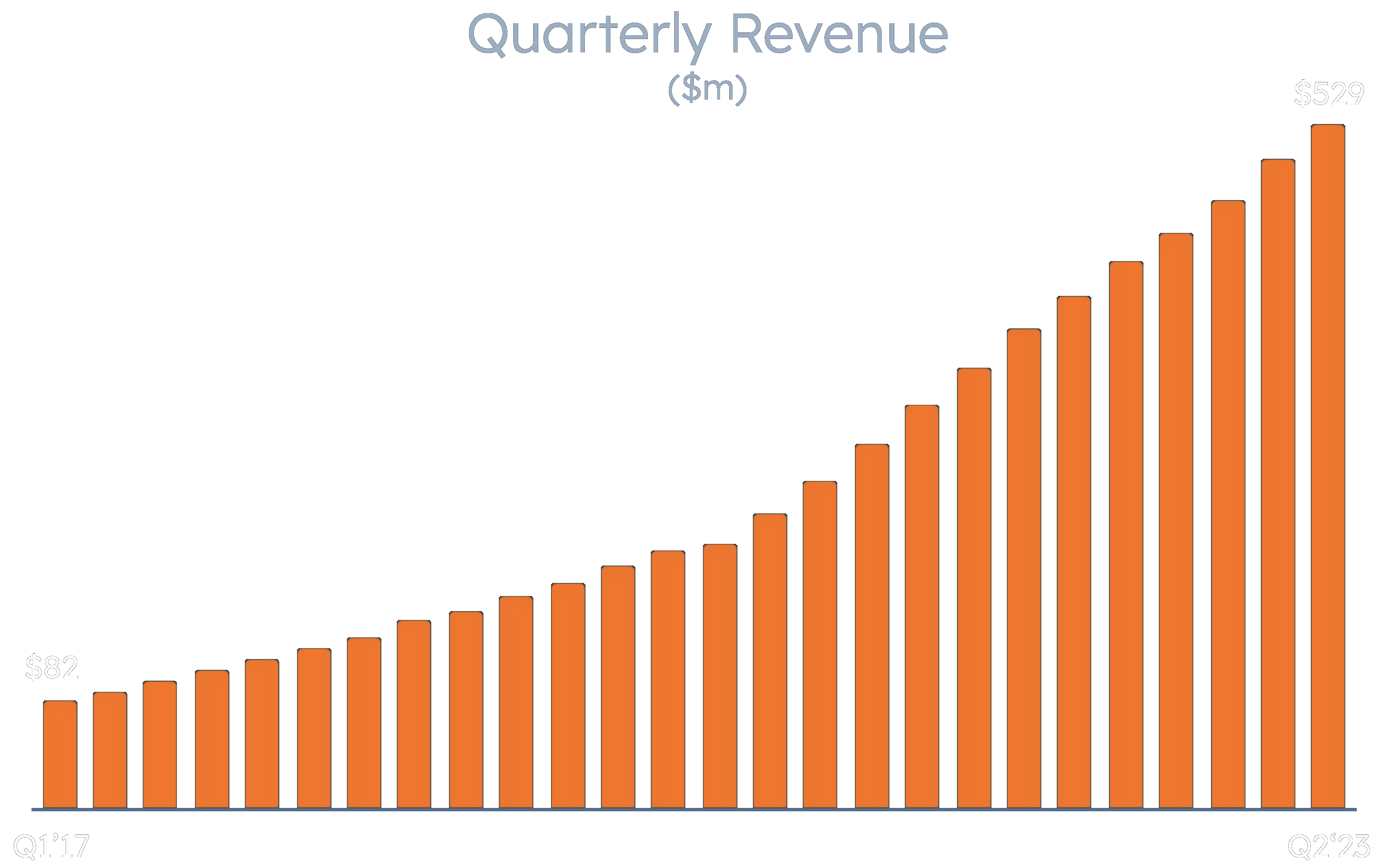

Sometimes there’s another shift in the slope of the line, when the company adds a second successful product, expands to a lucrative new market, or changes its business model. HubSpot, after twelve years of linear growth, changes to a new (but still linear) growth rate around 2021, around the time their second product-line reached its own fit:

Figure 9: HubSpot’s at-scale growth curve, exhibiting a bend, and linear on both sides of the change

Viral products

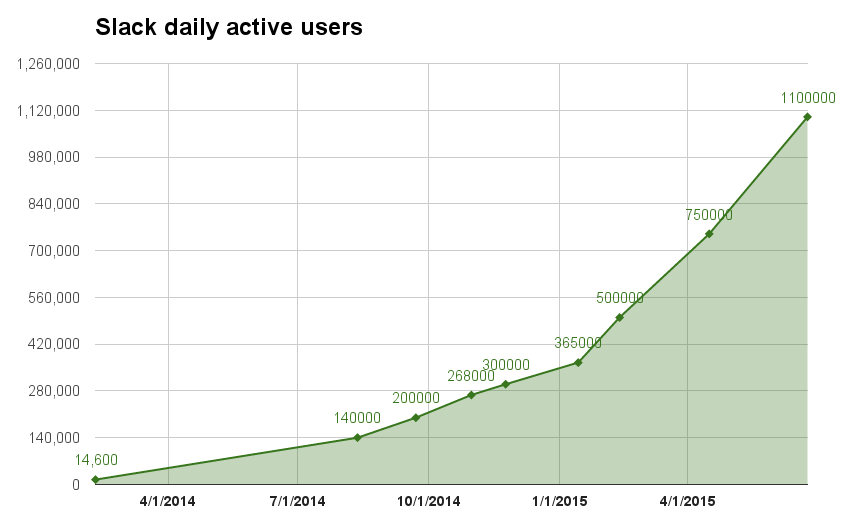

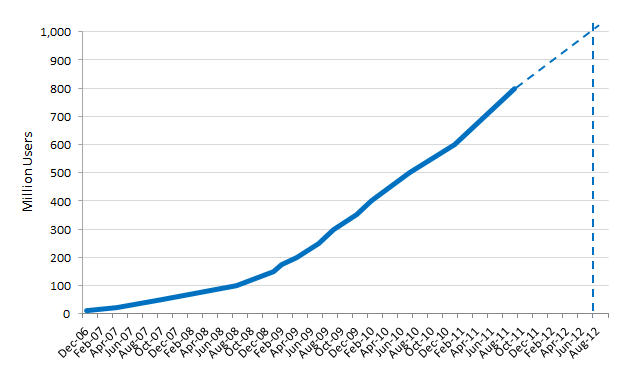

All of the previous examples were of B2B companies without “viral” or “network” effects, which are often associated with so-called “exponential growth.” However, even classic “viral growth” examples like Slack (at the time the fastest-ever-growing B2B company in history) and Facebook (at the time the fastest-ever-growing B2C company in history) did not grow exponentially. Instead, they grew in the same way again: linear, then a sudden change, then still linear but faster. Here’s Slack, which looks exactly like HubSpot:

Figure 10: Slack’s early user growth curve

And Facebook with a material bend in early 2009 (coinciding with the introduction of the “like” button that you could embed on your own website):

Figure 11: Facebook’s early user growth curve

Elsewhere I’ve gone into great detail about why even viral products like Slack and Facebook specifically don’t grow exponentially.

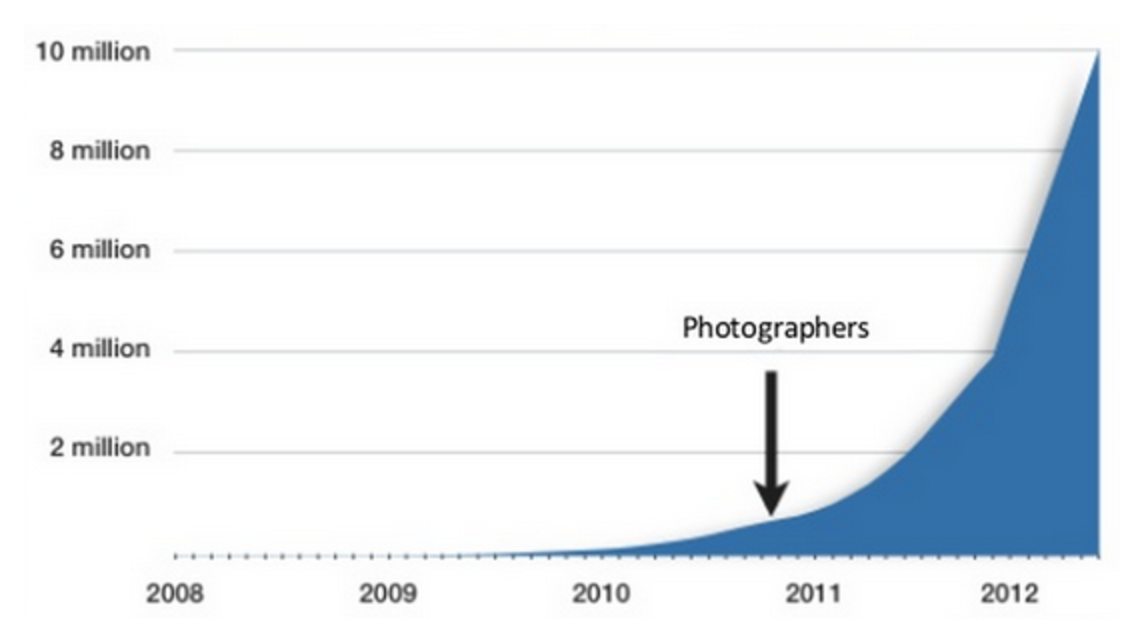

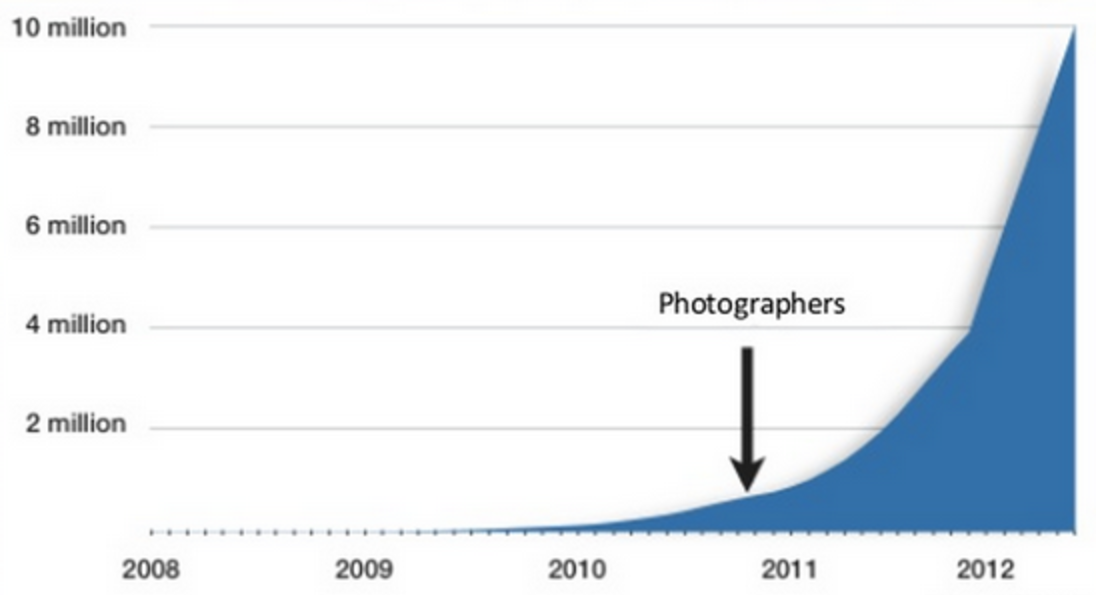

You can also see it in AirBnB with a bend in late 2010, coinciding with the realization that professional photography was the key to “fitting” with customer expectations:

Figure 12: Airbnb’s final piece of the puzzle

Media products

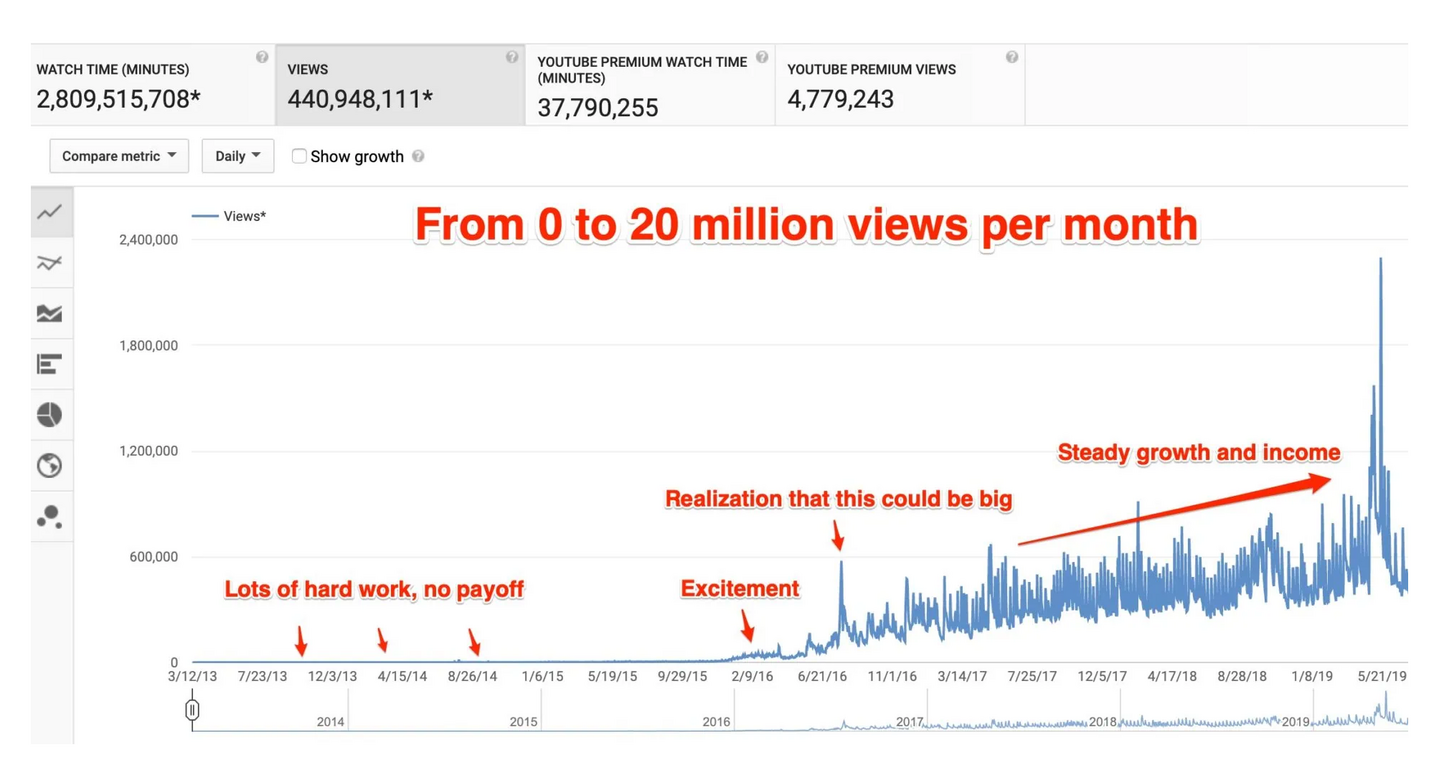

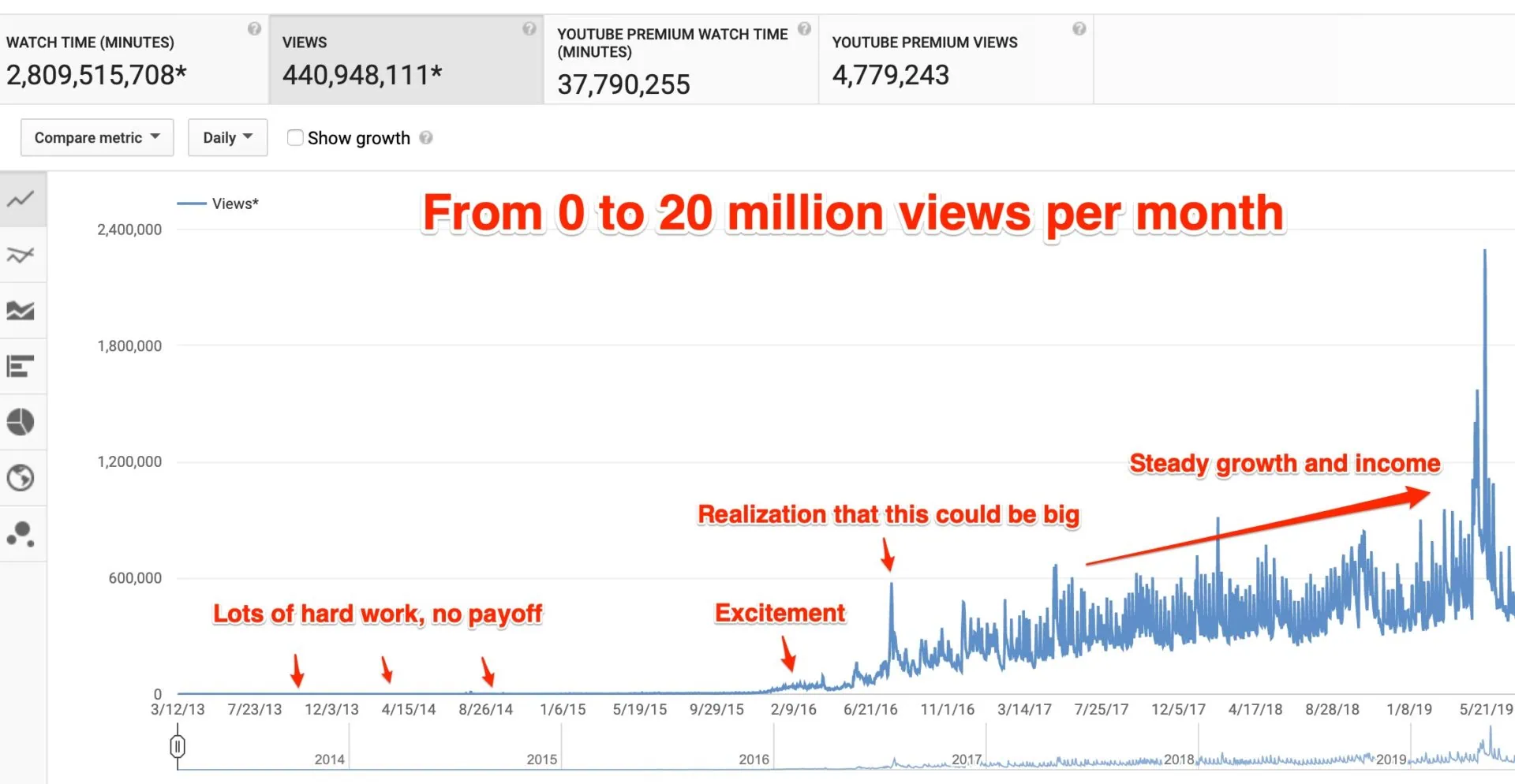

In many ways, media and content is unlike building and selling products. But in growth curves, and this characteristic PMF curve in particular, they are similar. Here’s one for a successful YouTube channel:

Figure 13

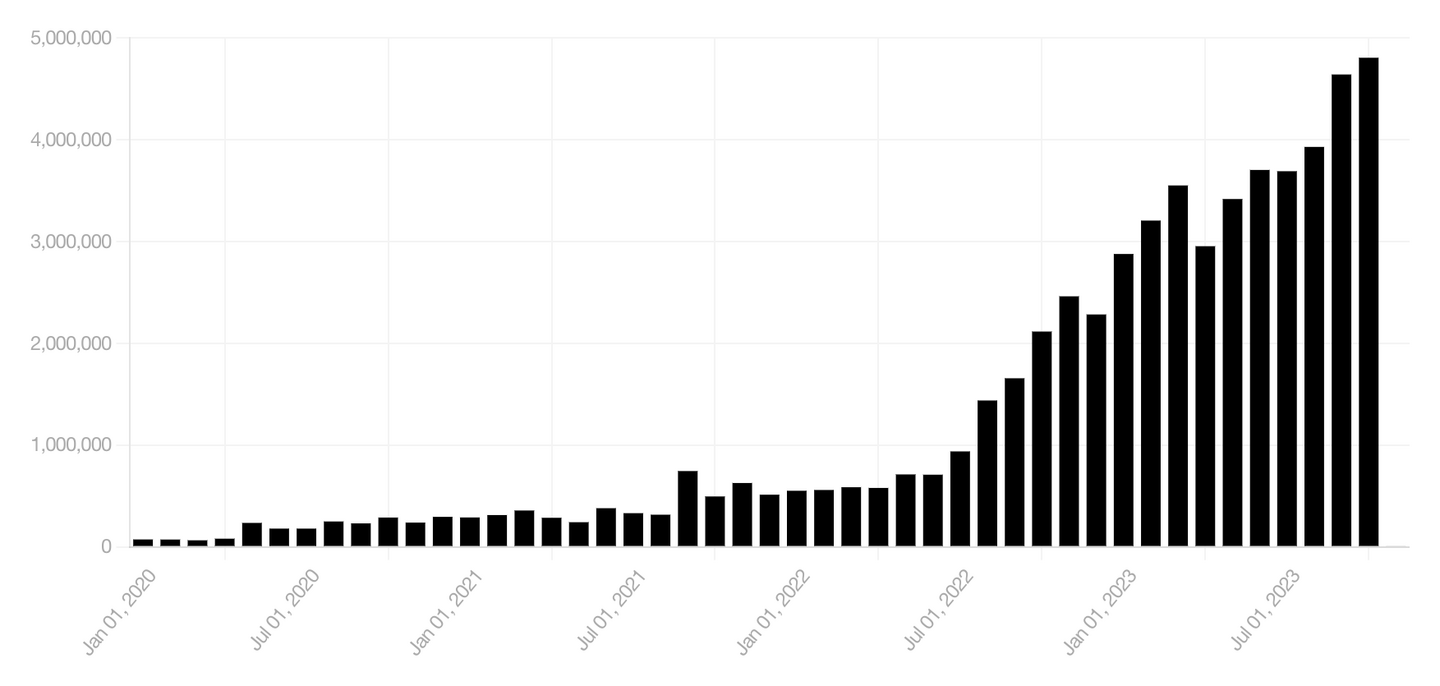

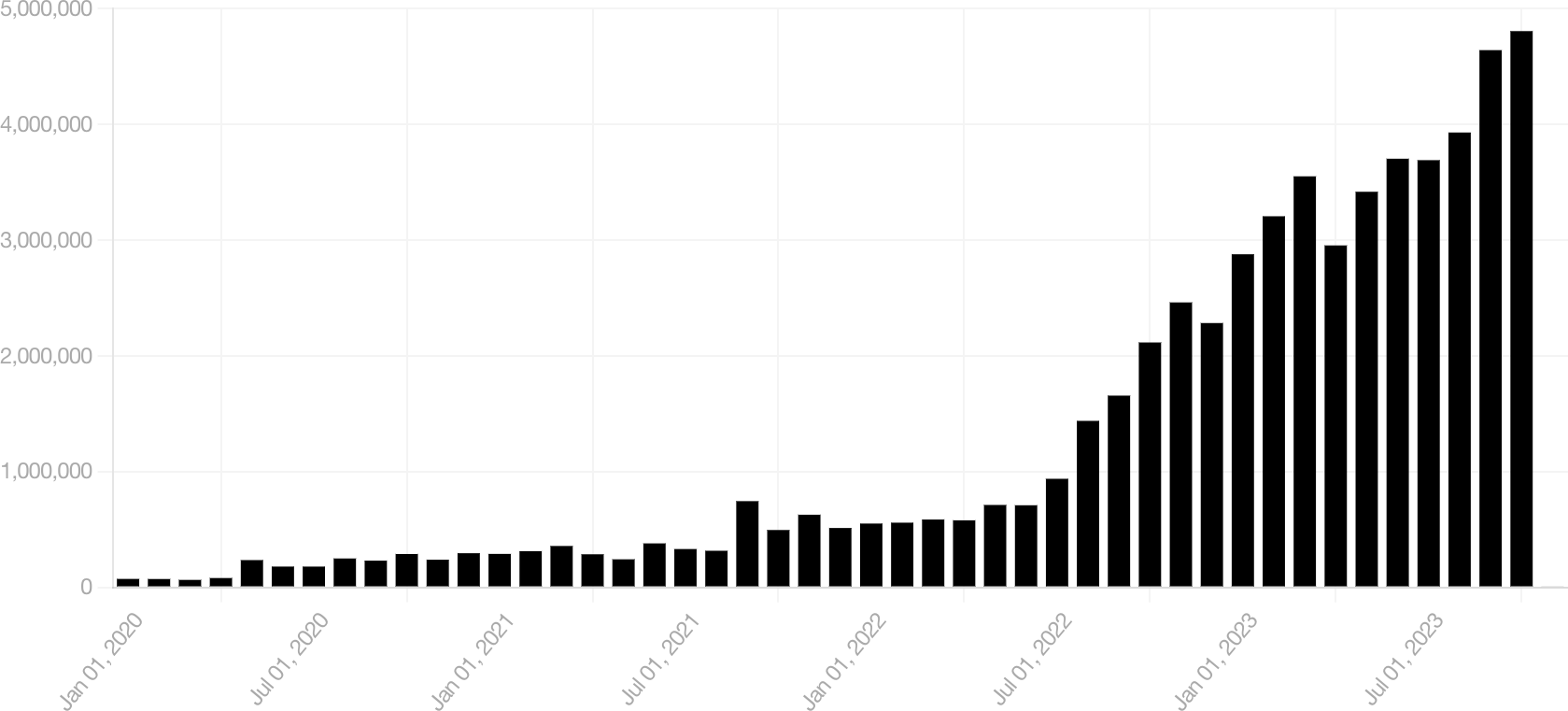

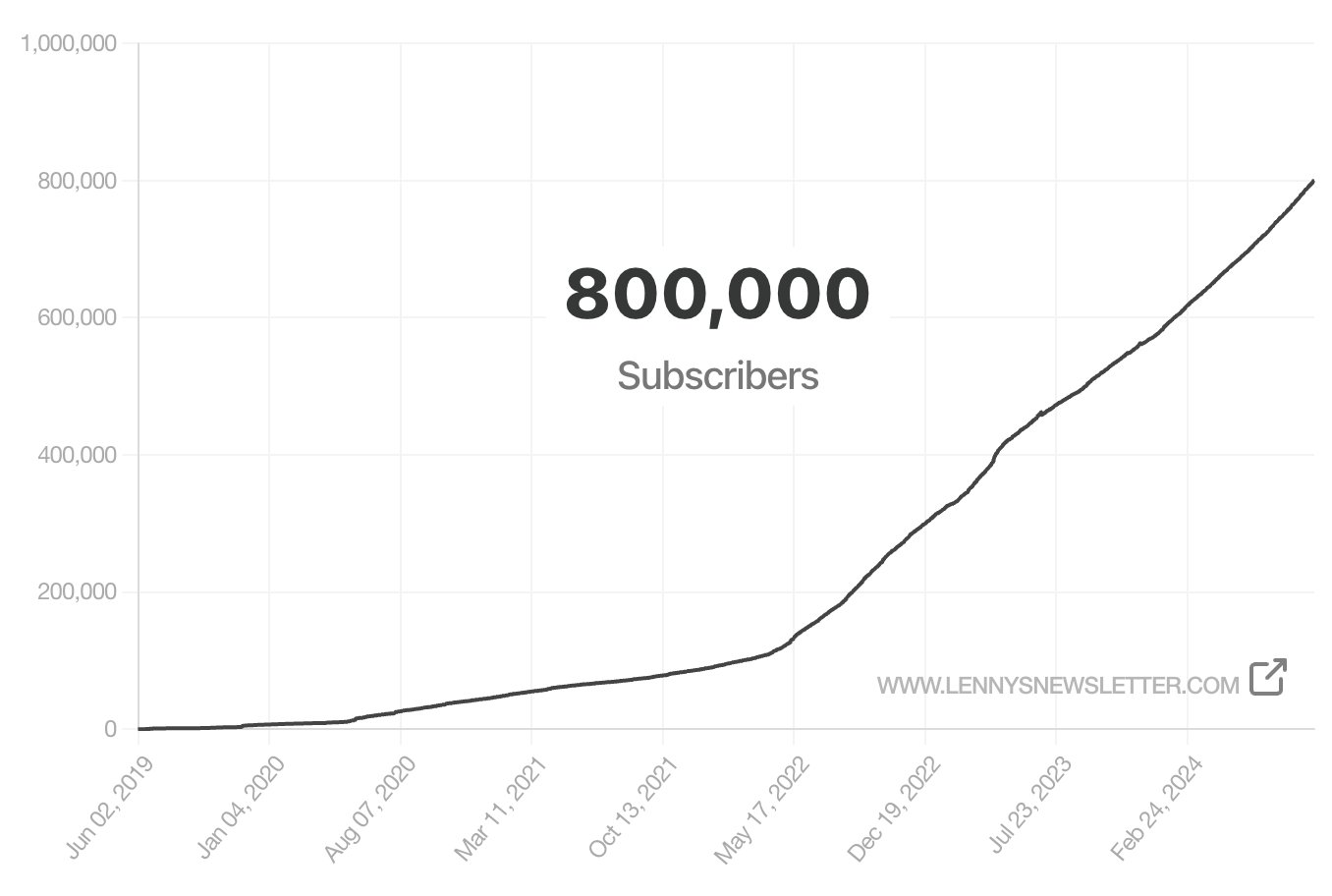

Or email newsletters like Lenny Rachitsky’s:

Figure 14: Lenny’s Newsletter traffic

Oh, and what did Lenny do to cause that sudden growth? You guessed it:

Figure 15

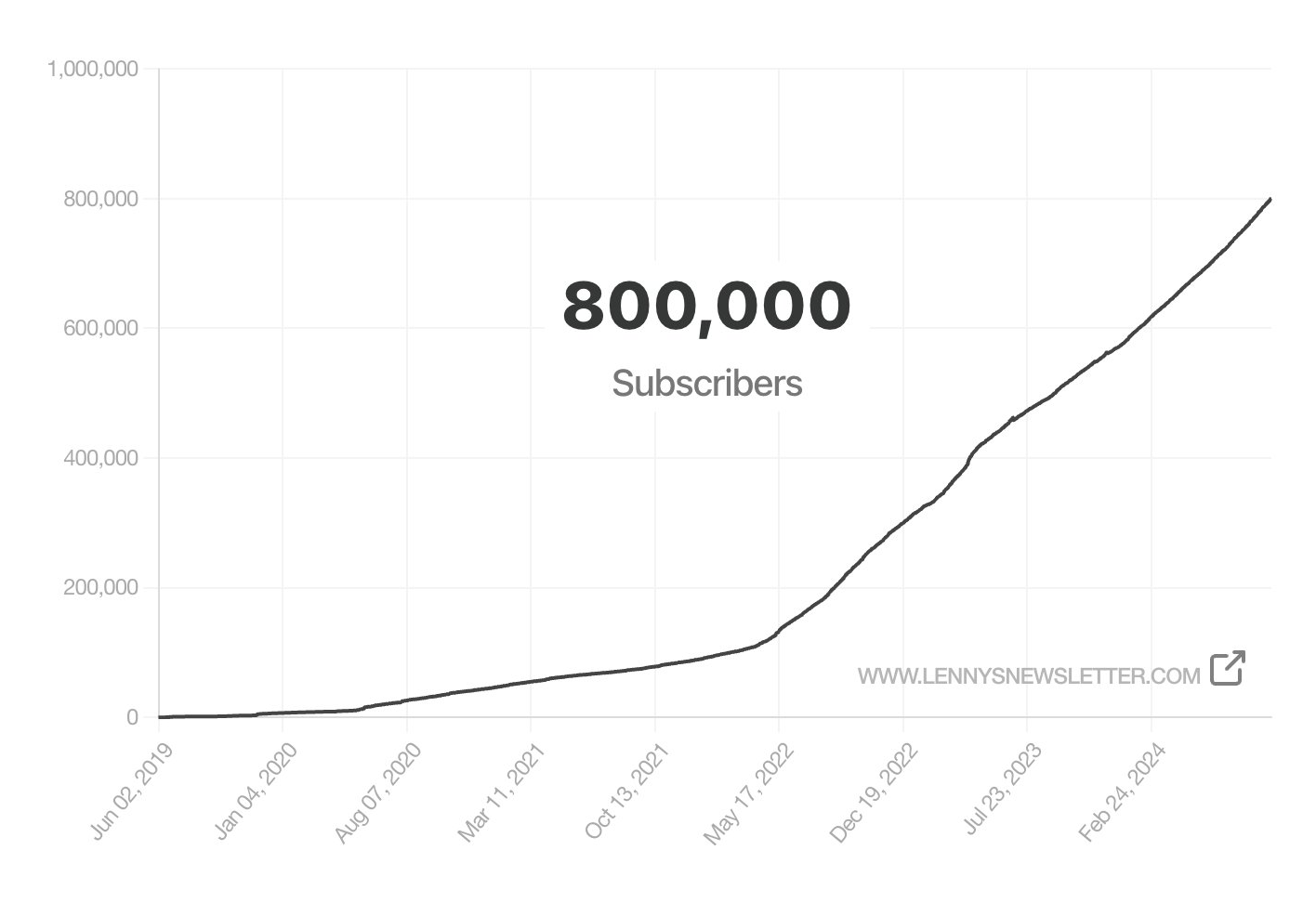

Update: Sept 2024: A year later, Lenny published his subscriber chart, and sure enough the pattern continues:

Figure 16: The first small bend in 2020 resulting in a line with a new slope, then the dramatic bend in May 2022 with nearly perfect linear growth for the next two years.

The bottom line is, these growth curves matching “fit” are common with all business models—B2B and B2C, recurring-revenue or one-time revenue, products or media, self-funded or VC-funded.

High cancellation means there’s no fit

There is one killer metric that will stop growth in its tracks, even with the curves above: Cancellation.

Founders often think cancellation of 5-7% per month is OK so long as they’re getting lots of new customers. But they are mistaken.

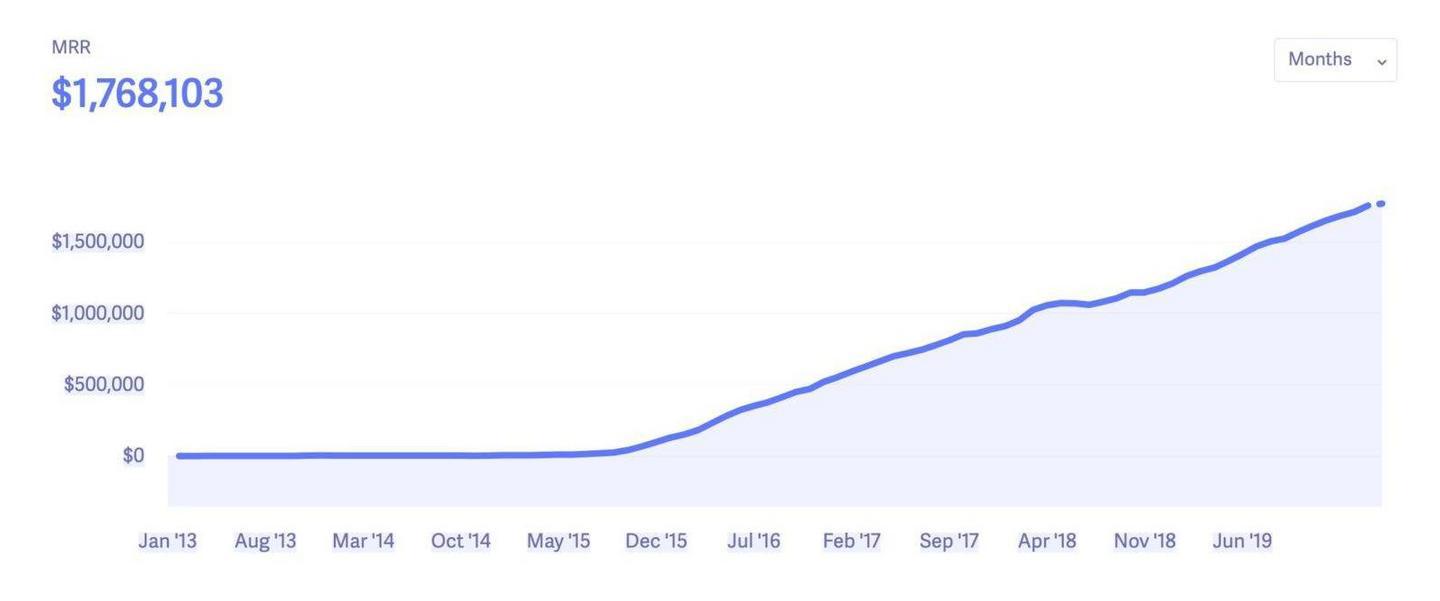

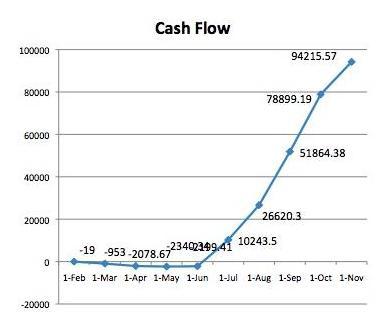

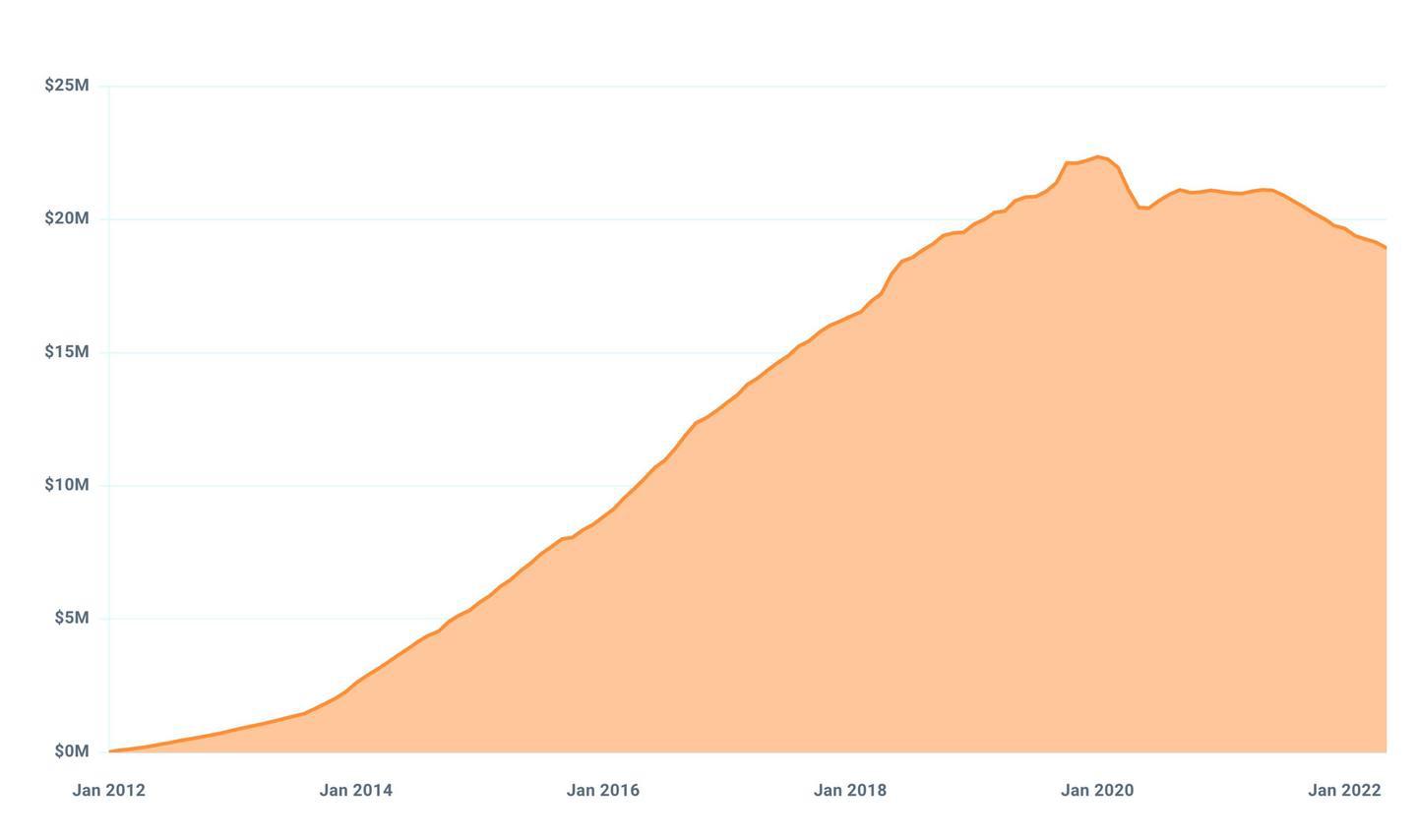

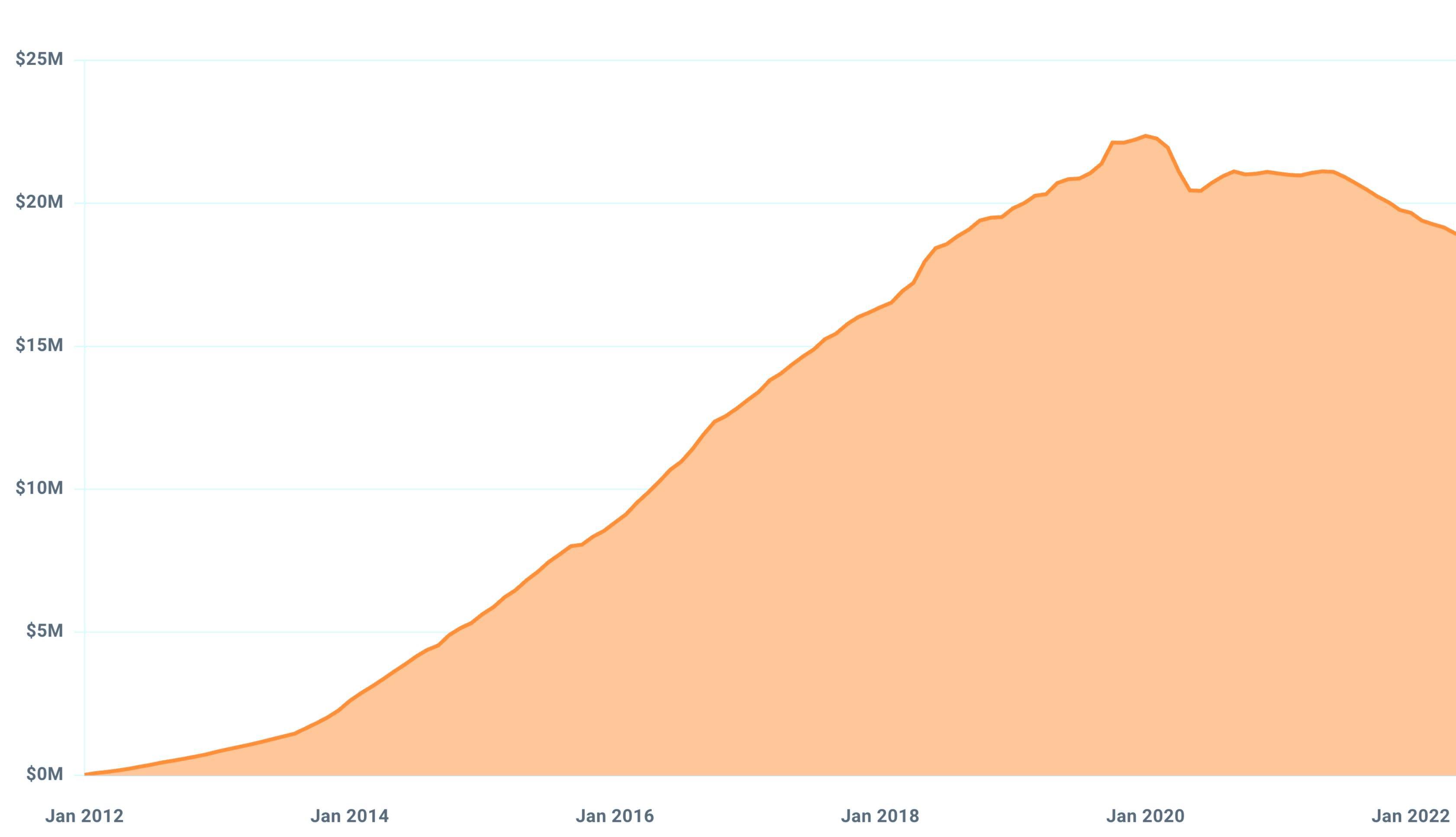

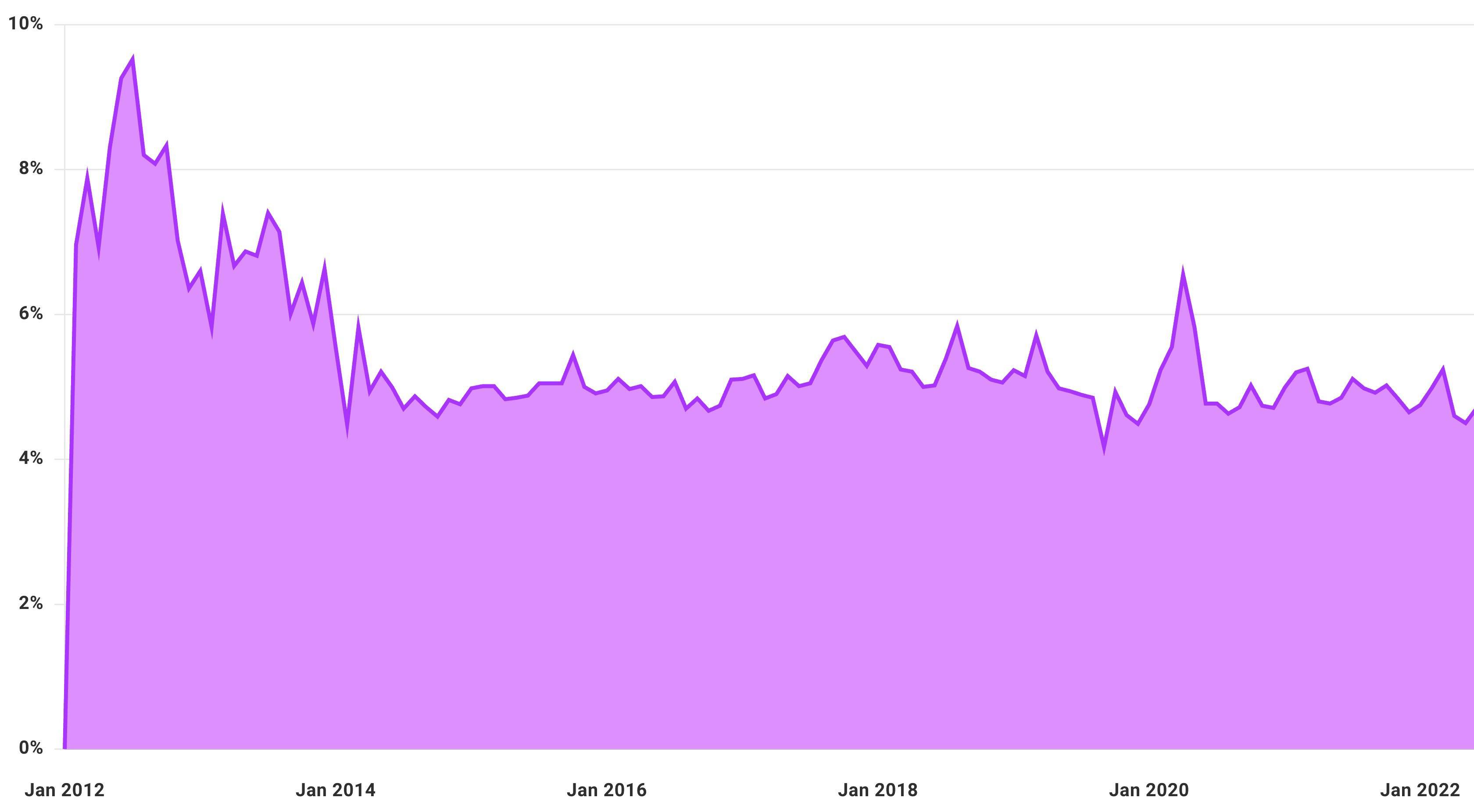

High cancellation puts a ceiling on growth. This is on public display with Buffer, who started with the same sort of linear-change-linear growth curve (2012-2014, then 2014-2020), but then growth leveled off (2020) and never returned (and even shrunk):

Figure 17: Buffer’s ARR

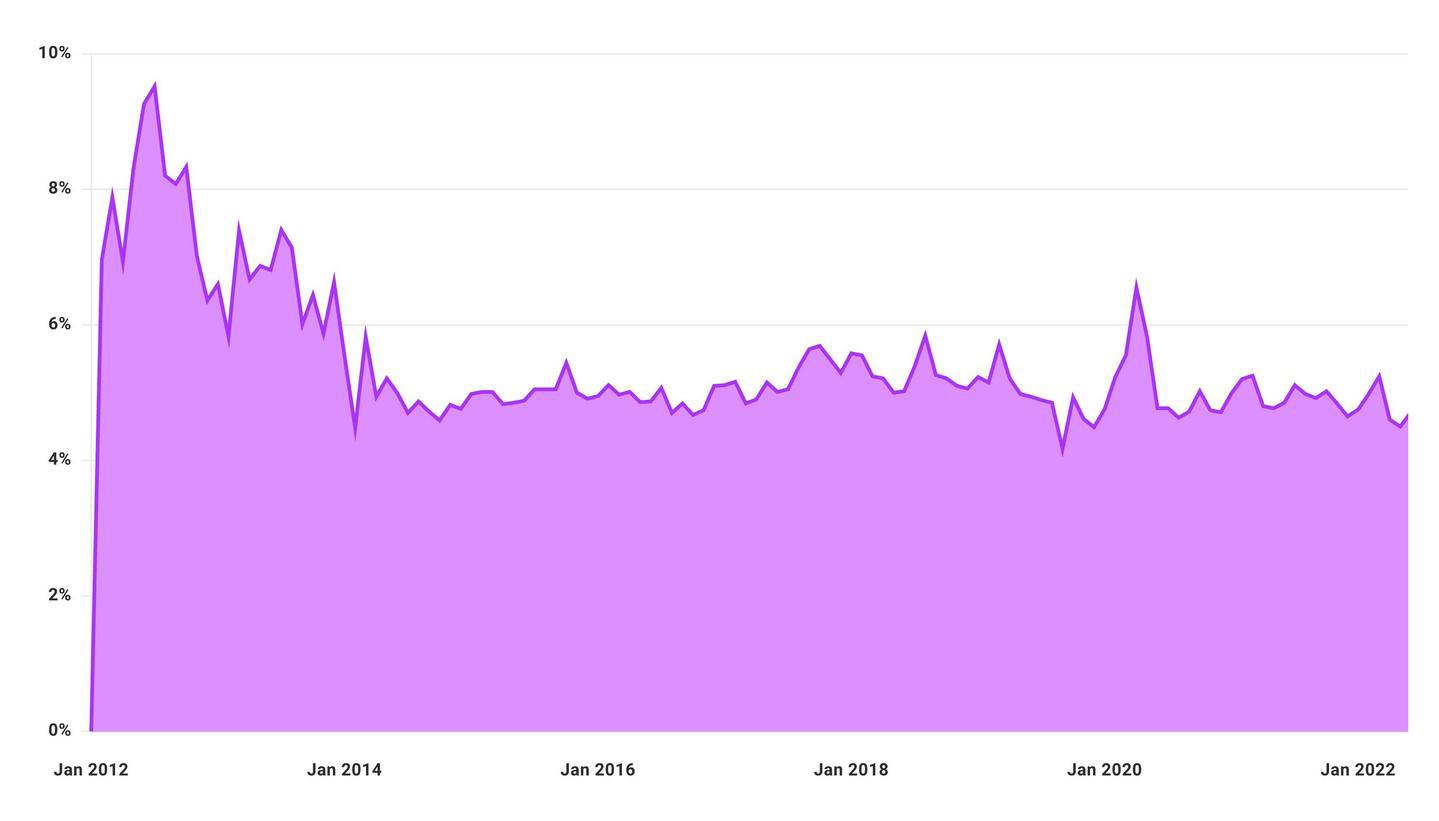

The reason is churn. Note how churn was higher during the slow-growth period of 2012-2014, then reduced to 5%/month, permitting faster growth:

Figure 18: Buffer’s monthly cancellation rate

But 5% is still too high; there’s no way to keep increasing new-customer acquisition to outpace churn, for the simple reason that “5%/mo” definitionally grows in lock-step with your total size, but marketing and sales does not continue to automatically grow just because your company is bigger. So, cancellations always win that race, and at 5%/mo, you top out pretty quickly:

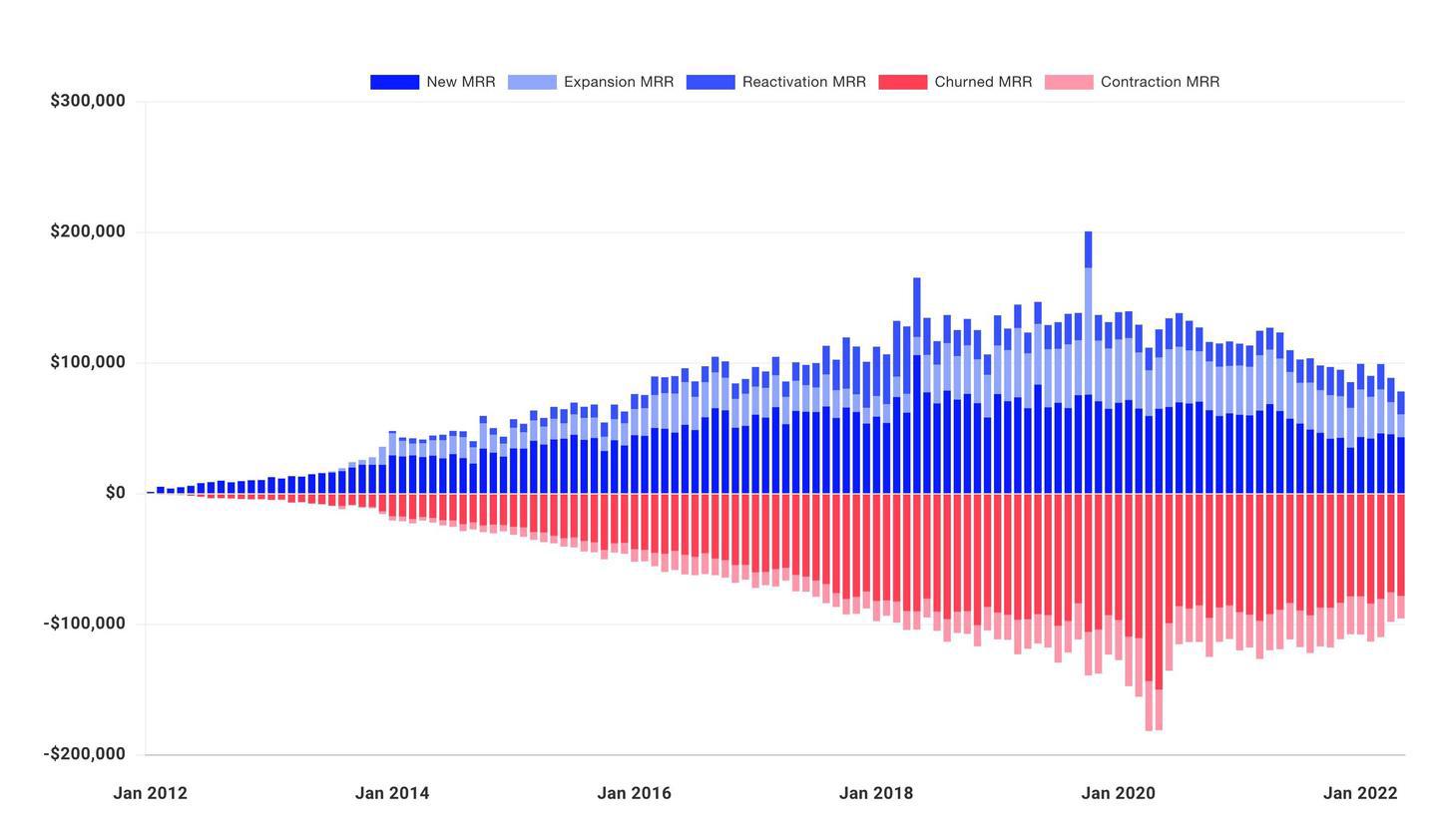

Figure 19: Buffer’s unit economics; new-MRR naturally tops out, whereas cancellation never stops growing in absolute dollars.

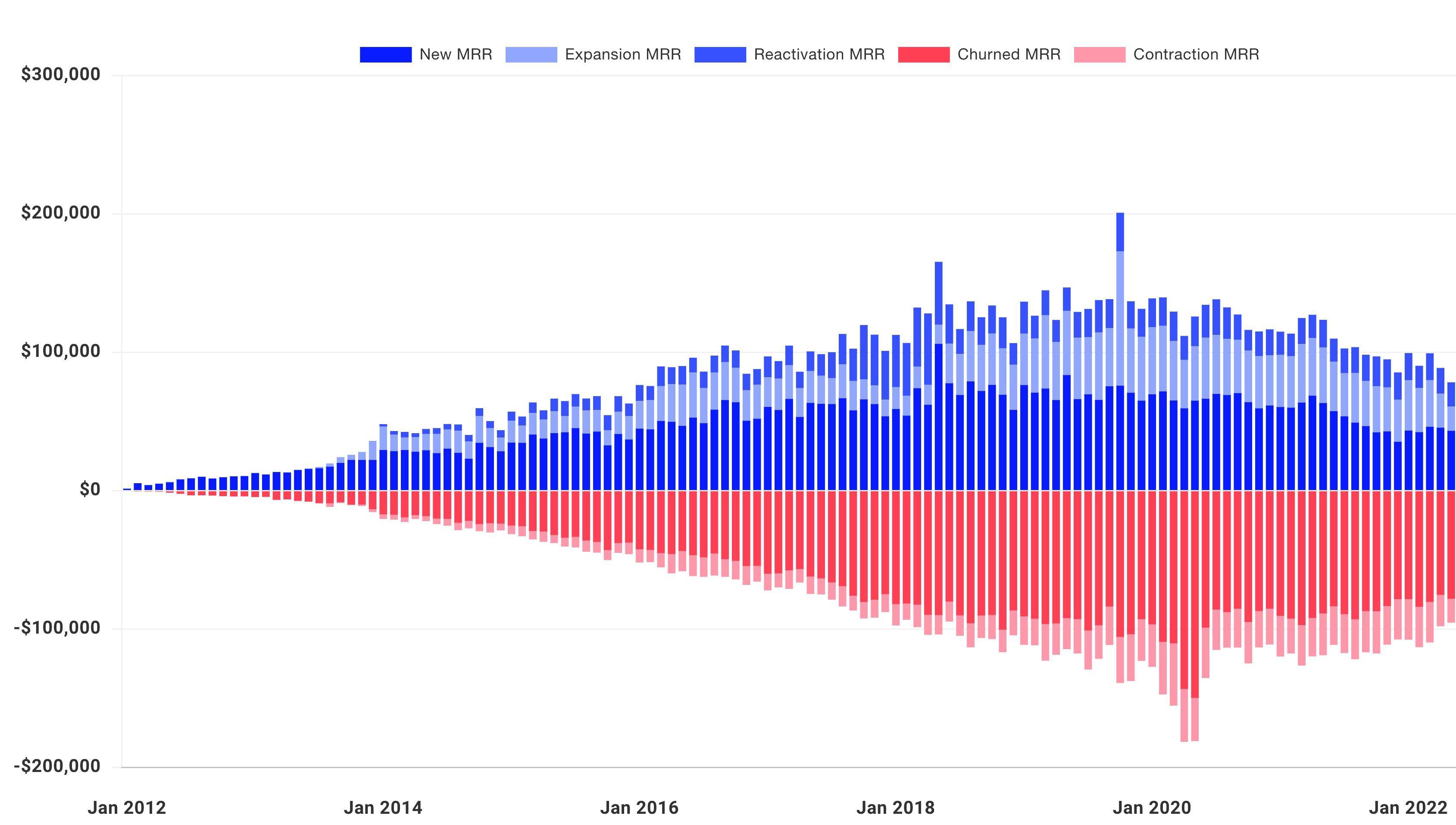

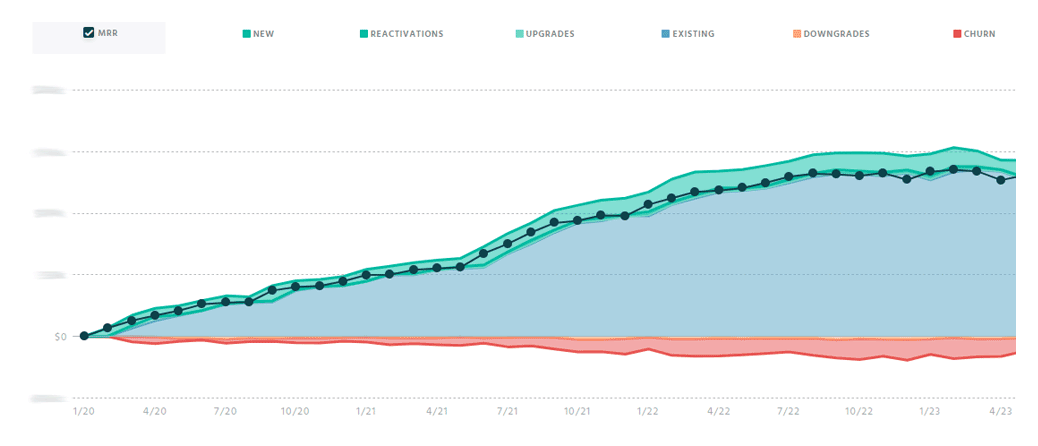

You can see a similar effect at SparkToro, an impressive company that is a testament to founder Rand Fishkin’s vision to build a great company instead of a company that attempts to accelerate growth forever; he explains how SparkToro generates enviable profit, with happy employees, happy customers, and happy investors. So this isn’t an indictment of the company, but it is a demonstration of the growth-destroying power of high cancellation rates:

Figure 20: SparkToro is consistent in adding the same dollars-per-month of new-MRR, but their consistent cancellation rate continues to grow in dollars per month, which means at their current size, cancellation “wins” that race, and growth becomes flat.

It’s not actually about finances; it’s the fact that customers are choosing to leave. The numbers are the objective measure that this is happening, but they’re not the point. The point is that customers don’t want to stay. That means it’s not a fit.

Therefore, both because “lots of customers leaving means it’s not a fit” and because high cancellations means the growth curve will quickly flatten, cancellation higher than 3% for B2B or 5% for B2C indicates a lack of Product/Market Fit.

Easy inbound growth is indeed a sign of fit, but if customers leave in droves, it means the promise was right, the price was right, but the product didn’t deliver, or the customer’s need was too brief to sustain a recurring-revenue business.

Some people call this “a fit, but not sustainable” or “a fit, just with limited upside.” I call it a lack of fit, because if customers are leaving, it’s not a fit.4 Don’t get distracted by dollars. Pay attention to customer behavior.

4 See this amazing five-minute segment from Twitch founder Michael Seibel, describing how his Socialcam app got 60M downloads in 4 months and ranked among the top 5 on the App Store, yet retention was so horrible (almost zero retained users after 10 days) that despite that inconceivable growth, it was not Product/Market Fit.

If your company is growing slowly, that doesn’t mean you failed. It just means you haven’t hit that success curve yet, and haven’t found Product/Market Fit.

Maybe you never will, but you’ll grind out a profitable company anyway. Maybe you never will, and growth is so slow, it’s best to face facts, stop, figure out why it was too hard, and try something else. Or maybe your growth spurt will start today. It’s impossible to know.

Maybe if you follow my roadmap to Product/Market Fit, which I used to build a unicorn, you will succeed. Then again, in that same article I explain that my previous startup used only half of those techniques.

No one knows; that’s life. But now you know what it looks like, when it is truly a fit.

Or that you still have work to do, if you’re not there yet.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/product-market-fit/

© 2007-2025 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear Simple eReader (Kindle)

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF