What makes a strategy great

Strategy is: How we will win.

You can debate the form a strategy should take, whether a four-sentence “master plan” or a few dozen bullets or a six-pager or an eighty-pager or a template like Salesforce’s V2MOM or a Notion template you found on the Internet or answering three questions from a Twitter pundit or some sort of “ Canvas.” Regardless, its job is to communicate “how we will win.”

There are a lot of documents titled “Strategy,” but very little great strategy. The formula for great strategy isn’t decided by the format of the output document.

Greatness needs luck, but it’s never by accident.

—Unknown

For strategy to correctly determine and communicate “how we will win,” it must tackle the reality of complex systems, it must parry the follies while exploiting the strengths of human nature, and it must justify and spell out the decisions which lead to the desired outcome.

Great strategies accomplish this with the following characteristics:

- Simple: Reshapes complexity to be manageable and actionable.

- Candid: Dares to spotlight the most difficult truths.

- Decisive: Asserts clear decisions and accepts their consequences.

- Leveraged: Magnifies strengths into durable competitive advantage.

- Asymmetric: Defeats uncertainty with higher upside than downside.

- Futuristic: Solves for the long-term.

Without these qualities, the so-called “strategy” is at best a plan; at worst, it’s wishful thinking masquerading as “vision.”

Simple

Simple can be harder than complex: You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it’s worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains.

—Steve Jobs

The world is complex, and therefore difficult to reason about. Strategy intentionally omits detail in exchange for clarity. Armed with a simple narrative, mere mortals can achieve understanding, and make every-day decisions that remain aligned to that narrative.

No one reads anything. You’re in the Top 1% just for reading this sentence. No one remembers anything. Certainly not an 86-slide PowerPoint.1 So the strategy has to be simple—even simplistic—to have a chance at being read or remembered.

1 Long supporting documents are useful, because they explain and justify complex topics, inspiring conviction even in people who don’t read it but are impressed by its size. Even the famously pithy Tesla “Master Plan” strategy consisting of just 39 words was preceded by 1200 words of justification.

People are mired in their day to day work; only when the strategy is simple, does it have a chance of being incorporated. Only when the context is over-simplified, having made scrutable the complexity of the real world, can we easily explain “why,” and retell those stories in our weekly meetings and prioritization sessions. Those are the places where strategy lives and breathes, where teams can move quickly, independently, fulfilling their individual missions with a minimum of coordination, yet all supporting a common theory for how we will win, together.

The bigger the project, the more we need a reminder of the goal, and simple things to execute today.

—Warren Buffett, shareholder letter, 1982

If the strategy is simple, it might appear obvious. If it is obvious, it might appear uninsightful. Humans assume that complex puzzles require complex answers, when in fact often the simplest answer is the best answer.2 “Obviousness” is a sign of a strategy that not only is easy to communicate and execute, but also believed.

2 See, for example, the Midwit Fallacy, or how small sets of equations explain a wide range of physical phenomena.

Its job isn’t to be non-obvious, but rather to cleanly specify what is most important. It might be obvious to do X, but Y and Z are also “obvious,” so by selecting X and not Y nor Z, you have created focus, and specified “how to win.”

Simplicity at its worst becomes reductive—overlooking complexity rather than tackling it, resulting in conclusions that, while admittedly simple and clear, are wrong. We cannot pretend that complex problems can always be waved away by simple statements. The process of strategy creation must indeed tackle the complexity of the world, but the output of that process is a document that frees everyone else from having to re-solve every puzzle. Like a street map, we omit detail in exchange for clarity of the most important context and routes. Simplicity that ignores reality is reductive, but simplicity that arises from an exceptional summarization of having already processed the messy, complex world, is elegant.

Characterizing the world in a few, simple, clear assertions, and solving our challenges with a few, clear directives of what we must do, is required for a strategy to be “how we will win.”

Example: The most famous sports coaches seem to credit their success to a few simple principles. They must be simple for a team to remember them, especially when they’re tired and battered near the end of a game, as in this description of the mentor of one of America’s most famous football coaches:

“Blaik’s signature talent was using all this data to create something clean and simple. He had what Lombardi called “the great knack” for knowing what offensive plan to use against what defense, and the “discarding the immaterial and going with the strength.” All the detailed preparations resulted not in a mass of confusing statistics and plans, but in the opposite, paring away the extraneous, reducing and refining until all that was left was what was needed for that game against that team. It’s a lesson Lombardi never forgot.

—David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi, 1999

Candid

See, and don’t be afraid to see what you see.

—Ronald Reagan

Strategy must lay bare the most frightening, embarrassing realities. It must face the truth that we all avoid facing during the struggle of daily work.

If the strategy doesn’t expose—and then solve—the most brutal facts, the strategy is wrong.

In particular, the strategy must diagnose the primary challenges facing the business, even if the facts are so scary that it seems hopeless. Existential threats are the most important to articulate.

Too often a strategy claims “threats” that are lazy, generic, non-actionable pseudo-concerns that nearly every company could claim, like “Google could copy us” or “A new startup could invent a great product and get huge funding” or “A massive security breach could cause half our customers to leave.” Real threats are either happening now or are at least 70% likely to happen. Real threats are specific, ideally backed by data that proves they are happening, e.g. your market is shrinking; a competitor has accelerating market share; cancellation rates prove that even paying customers don’t value the product. Real threats are written in the present tense because they are happening, not hypothetically with “could” or “might.”

When the puzzles are clear, everyone can help solve them. When the puzzles remain hidden, what’s the chance that they’ll be solved by accident?

Average players want to be left alone. Good players want to be coached. Great players want the coach to tell them the truth.

—Nick Saban (won more US national college football titles than any other coach)

If you’re worried someone might leave the company when they hear how scary it is, maybe they should leave the company. These are the challenges we’re facing together; if they’re not willing to solve them, they need to make space for someone who will relish the challenge. Not just for the company’s sake but for their own happiness and fulfillment.

Facing the truth, being specific about current reality and about what needs to be done, is required for a strategy to be “how we will win.”

Example: In a story retold here, originally from Jim Collins’s book Good to Great, A&P and Kroger were successful grocery stores in the 1960s who both possessed the data showing that their business models were becoming obsolete. They each discovered the new, correct business model through real-world experimentation, but only Kroger was willing to face that truth and change their strategy. Despite being half the size of A&P, Kroger increased its value 100-fold, while A&P shrank, then went bankrupt.

Decisive

A strategy asserts a set of justified, self-consistent decisions, such as:

- Which subsets of the market to target

…and conversely which we’ll ignore, even if some of those sign up as customers anyway, and ask for things we’re not going to do, and then cancel in anger - Which customer personas are most important to delight

…and conversely which will dislike our product, causing us no dismay, whose feature-requests we will quickly close as “won’t do” rather than wring our hands at all the features we still need to build - How to position against the competition

…and conversely where the competition will be stronger, unlike those fake-news marketing charts comparing our product with the competition, where only our product scores 100% along every dimension - What we value (e.g. quality, service, speed, design, compatibility, lock-in)

…and conversely what we will give up, e.g. releasing features faster but of lower quality, or being infinitely extensible versus top-to-bottom thoughtful design - What we must (and must not) build, to pay off that positioning and win those customers in that market.

You can do anything, but not everything.

—David Allen

There are both positive and negative second-order consequences of any complex decision. If these aren’t identified—in particular, if the problematic consequences aren’t embraced within the strategy—then it’s not a clear decision. When those consequences inevitably arise, the team must be able to say “we expected that” rather than “we have to address that” or even “this is a signal that the strategy is wrong.”

One decision in every strategy is what market and customer-segment the company will target. Customers outside that target segment will inevitably buy anyway. Then they’ll complain about missing features, awkward UX workflows, missing integrations, high prices, and more. Then you’ll log those complaints into the bug-tracker and product-management Miro boards and start prioritizing, whereas in fact these ideas should be ignored so that the team can focus on winning the target customers. This is difficult to remember when the non-target customers complain on Twitter, supply low NPS scores, drag down your average star-rating on review sites, and cancel at high rates. Only with a strategy that has clearly articulated not only the decisions, but also the negative consequences of those decisions, can everyone stay true to those decisions even when emotions are running high and paying customers are canceling.

A common tactic for avoiding making a decision is to use non-specific language. “We will leverage synergies to create unique solutions” is, in fact, a good thing to do, but it doesn’t specify which synergies to leverage, what is unique about it, or what the unique solution is. Fluffy language is a hallmark of indecisiveness, and therefore of bad strategy. Being specific is good marketing, anyway.

Strategy is a set of interrelated and powerful choices that positions the organization to win.

—Roger Martin

The opposite of the decision must also be a rational choice, made by other successful organizations. For example, deciding to be open source is strategic, because plenty of companies are successful with a closed-source strategy. However, deciding to be “customer-first” is not a serious decision, because successful companies don’t use a “customer-last” strategy. This “Opposite Test” is useful both to form proper strategic decisions, and to form great positioning statements for marketing.

Decisions and consequences must at minimum be self-consistent. If you’ve decided to have a low price, you can’t also have white-glove service. If you’ve decided that everything requires high-quality design, you can’t also release features faster than the competition. Or, perhaps you can creatively build a solution that does say “yes to both” of those things, but only by also accepting additional constraints that resolve the conflict.

Better than “self-consistent” is “mutually-reinforcing.” This means that one decision makes another more powerful, or easier, or less expensive, and vice versa, so that adhering to both makes you far stronger than having only one. For example, deciding to have only a few features, and also amazing design. Normally customers might not put up with less functionality, but if the design experience is exceptional, they might be happy with something that “does only a few things, but so delightfully!” And vice versa: It’s easier to execute on great design when you don’t have to tackle a complex product with tons of use-cases and personas and functionality. At the end of this article, you’ll find a complete, powerful example of mutually-reinforcing decisions creating a durable (60-years!) competitive advantage.

The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.

—Warren Buffett

You know the decisions are strong when they—and their consequences—cause you to say “no” to most things, including things which otherwise sound reasonable. An example of a strategy that makes a decision but also accepts negative consequences can be found at the end of this article about Moats; an example of how to make sales pitches while accepting negative consequences can be found in this article; several examples of how YouTube used a single, strong decision with multiple major downstream consequences are detailed in this article.

When a strategy has articulated clear decisions, including the major consequences, especially accepting the negative consequences, causing us to say “no” to pretty-good ideas in order to make room for the very-best ideas, and to ignore the wishes of paying customers if they’re not the target paying customers, it is truly prescribing “how we will win.”

Example: Craig’s List is classified ads on the Internet. Their strategy includes crisp decisions like valuing consistent user experience more than great design (the website looks like it’s from 1995, because it is), and user-accessibility over monetization (“Craigslist president Jim Buckmaster has stated that creating a superior user experience is more important to the company than making money [ source]”). The strategy is clear and differentiated, which should be seen as a strength, but it has bothered pundits for twenty-five years, who have therefore predicted its demise: “The main obstacle to sustainability and growth at Craigslist is likely the company’s and its founder’s strong principles valuing customer-offering over monetization, trusting consistency over innovation. Although admirable in many ways, the issue is that without innovation, the company’s customer-offering will soon no longer be strong enough to stay relevant, undermining its very well-intended purpose.”— HBS. But crisp decisions make for a great strategy, even if controversial. Despite that well-reasoned death-sentence from HBS, despite others pointing out that dozens of successful companies have made sections of Craig’s List theoretically obsolete, despite data that predicts Craig’s List “demise”, despite protestations that Craig’s List could be a “gold mine of revenue, if only it would abandon its communist manifesto,” (i.e. if only it would abandon its strategy), it continues to be one of the most-visited sites in America, with revenues of $1,000,000,000 in 2020 with a staff of just fifty people, even after twenty-five years of Internet evolution.

Leveraged

Be yourself. Everyone else is taken.

—Oscar Wilde

If Sandra is a great singer, and Peter is a great pianist, then a good idea for a duet would be for Sandra to sing and Peter to play piano. A bad idea would be the other way around. Great strategy leverages the strengths and assets of the organization; a bad strategy asks the organization to win even while acting unnaturally, often under the cover of “overcoming weaknesses.”

“Leverage” means generating a large effect from a relatively small effort, where time and dollars are far more effective than one might expect, because we are riding tailwinds of natural abilities or hard-won assets, rather than fighting a battle against so-called “weaknesses.” You know you’re leveraging strengths when you see other people shake their heads in amazement at how much you accomplished in so little time.

It’s good to leverage strengths. Much literature on strategy dwells on how to create moats—permanent competitive advantages—but so many organizations still aren’t leveraging the straightforward, undifferentiated strengths that they possess. They expend most of their energy shoring up “weaknesses,” which despite their efforts will at best become “less weak,” but never become a strength. Whereas applying that same energy in leveraging their strengths will have a large positive effect. It’s even just more fun to play to your strengths instead of wallowing in weaknesses.

It is of course better when the strength is differentiated from the competition. This is especially obvious in a mature market where everyone is saying the same things on their home page, pricing the same way, and different only in tertiary characteristics. Winning in your own way can defeat “better” competitors.

It’s even better when that differentiation is durable over time. It has never been more difficult to establish a permanent advantage, when all software can be reproduced, all business models can be replicated, and the entire world is both your market and your competitors, which makes it all the more important to decide what one or two moats you will build. The strategy is the place to name those moats.

This companion article on “leverage” provides expanded examples and ideas for all of the above.

Tailoring the decisions for the strengths of this organization, avoiding (rather than reversing) weaknesses, even better when the strength is differentiated, identifying and investing in durable differentiation, so that moats are constructed in the long run, is required for a strategy to be “how we will win.”

Example: Zappos started in 1999—early Internet, no social media, few people with broadband, few people comfortable buying anything online, much less buying shoes, which for 100 years was bought only after first trying them on in person. Zappos started with a differentiated insight (the companion article explains how “insights” can be leverage): That people would actually buy shoes online, under the right circumstances. They built a moat out of a combination of surprising decisions (also explained in the companion article): (a) postage-paid returns even 364 days after purchase, (b) legendary support who did things like buying pizzas for customers, (c) a corporate culture of employee empowerment; it takes that combination of strong, expensive decisions to create the conditions by which people would dare to buy online, thus unlocking an entirely new retail channel. Only by having all three of those components did the moat work; if you don’t empower employees, they can’t order pizza on the spur of the moment; if your return policy isn’t ridiculously generous, people will be too scared to order shoes sight-unseen. Because their vision and decisions were so incredible (literally “not credible”), competitors laughed at them while they enjoyed a constant stream of positive press. The result was the most successful online shoe store for a decade, reaching annual revenues of $1B before its tenth birthday.

Asymmetric

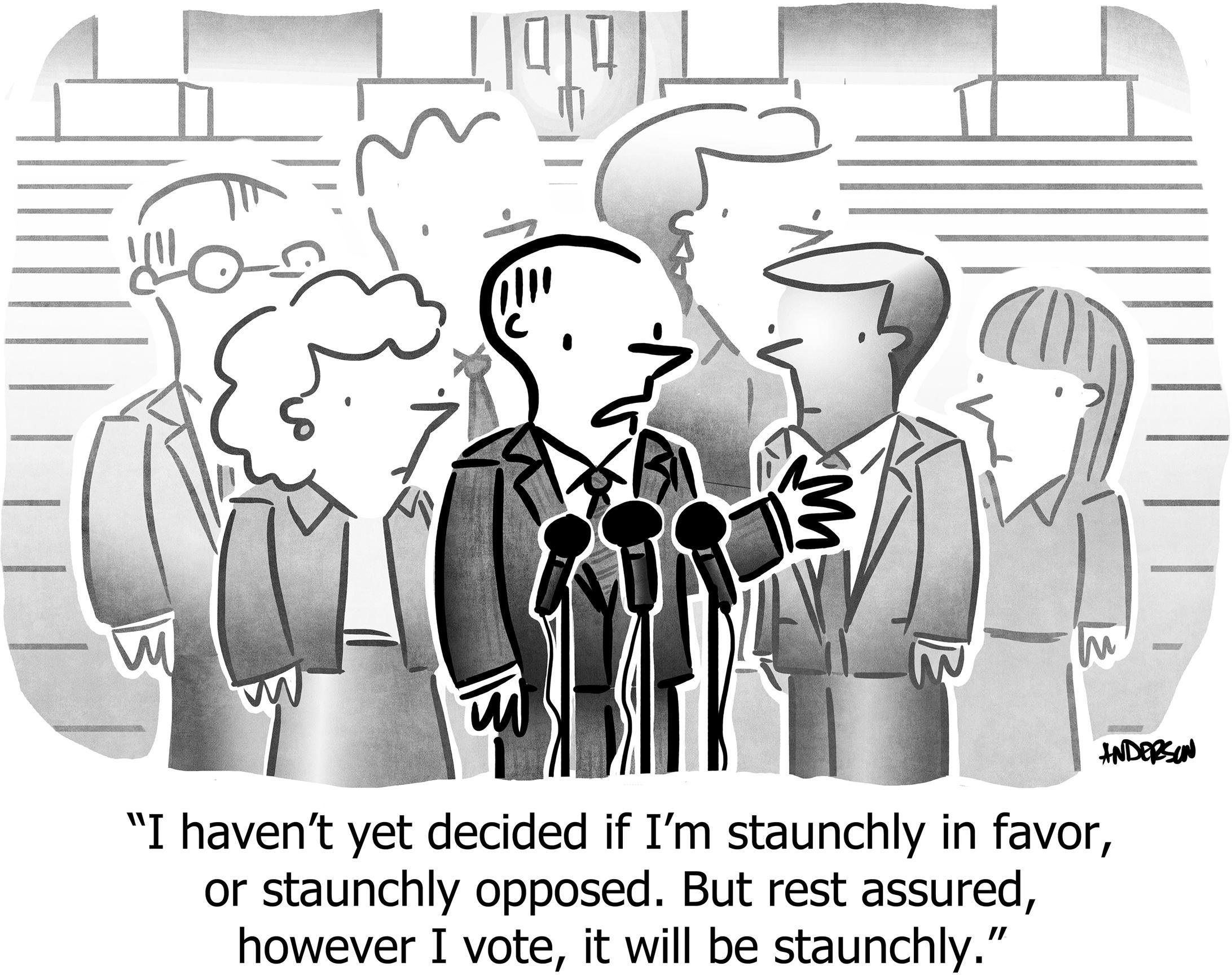

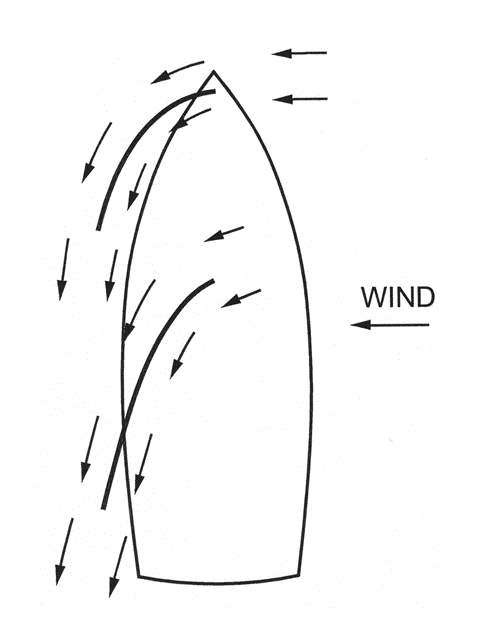

A sailboat always moves forward.

This remarkable fact is due to its asymmetrical shape: it is pointy at the front and flat in the back. This creates resistance to moving backwards, but a natural ease in moving forward. Even when the water is randomly undulating, “backward” forces are muted, while “forward” forces are allowed, so the boat glides forward. Asymmetries can amplify positive effects while muting negative ones, resulting in a net-positive force even under conditions of random inputs.

Great strategies prescribe activities that always move the company forward, despite the inevitable bad luck and setbacks. To do that, the activities must exhibit asymmetry, where the upside vastly exceeds the cost, so that even if you took 2x longer to achieve 50% of what you expected, you still win.

If riskier investments could be counted on to produce higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier.

—Howard Marks

This is the mechanism behind Venture Capital portfolios, which are investments in a slate of early-stage startups. The worst-case outcome for each bet is that they lose 100% of their investment, but in the best case they can gain 10,000%. A few large successes more than make up for the many failures, so the portfolio in total comes out positive. Investors call these “asymmetric bets.” Economists call this “convexity.”

Strategy must create a portfolio of bets having this “VC-like” asymmetric quality, whether for a small startup trying to find product/market fit or a mature company entering new markets. A sign of a bad strategy is when success requires everything to go right. With a set of asymmetric bets, the successes render the failures moot, and so the unpredictable waves crashing into the boat still result in forward motion.

This companion article details strategies that work well in an unpredictable world. One of the few strengths of a new startup is that it can learn faster, react faster, deliver faster; startups are favored when the waters are uncertain.

One form of asymmetric bet is entering a large and growing market. Besides the obvious benefits3 there is the asymmetry of optionality: There are many niches to exploit, many possible ways for a product to deliver value, many marketing and sales channels, and there’s more of all of it every year. Because there are many options to try, there are many ways to succeed; if your first few ideas don’t work, the next one might. By having lots of ways to succeed, you are more likely to find one. Waves on the boat.

3 Potential customers are already spending money, which means budgets are pre-allocated and pricing structures are well-understood, the press is already talking about it, marketing channels already exist, and the “pie” is growing, so even a small slice of the pie automatically grows.

The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.

—Albert Einstein

Another kind of asymmetry is a process that compounds, meaning that the more of it there is, the faster it grows. Things with this characteristic naturally grow larger than anything that grows in a more linear fashion, even if they start out small. Examples are customer retention, customer upgrades, and employee retention. Another example is a growth-vector that is proportional to the size of the current customer base, such as word of mouth referrals and viral products (e.g. once you join a social platform or collaborative online tool, you tend to get other people you know to join as well). Most things that grow non-linearly don’t grow exponentially—that’s normal, and still a great strategy. A common example is a reseller channel, because each reseller could bring you a number of clients over time, so when the number of resellers grows by N, the number of potential customers they bring grows by N ✕ M. For example, Intuit grew Quickbooks by providing software to CPAs that made their life easy, but only if their clients used Quickbooks. The CPAs started requiring their clients to buy Quickbooks, and so a smaller number of CPAs created a much larger number of Quickbooks sales.

In the negative, companies also face asymmetric threats. With ten competitors, only a few need to become break-out winners to pose a significant challenge. Like the famous statement by the IRA after a bombing failed to kill British prime minister Margaret Thatcher: “Today we were unlucky, but remember we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.” A strategy that places a number of asymmetric bets doesn’t need to be lucky always.

Every plan will face challenges, both foreseeable and bad luck. If everything has to go right for the plan to succeed, it won’t succeed. Whether a single investment has asymmetric upside, or a portfolio of bets collectively has large upside, exploiting asymmetries maximizes the chance that the strategy will succeed despite the inevitable travails and uncontrollable luck, and thus is vital to “how we will win.”

Example: Amazon is the cliché example, but only because it’s apropos, even ignoring AWS. Originally a book-seller only, they have never stopped taking bets, whether on adjacent markets (e.g. selling electronics), reselling internal systems (e.g. Amazon warehouses, logistics, robotics, fulfillment, were all broken apart and sold as separate products), or entirely new kinds of product (smart phones, cloud computing). More impressive is when the new bets purposefully disrupted previous businesses; according to early employee Andy Johns ( article, podcast), Bezos was so adamant that the Kindle be successful, despite the fact that it would hurt their physical book business, that he assigned the Kindle project to the executive who was currently over the book business, saying “Effective tomorrow, your job is to kill your old business with a Kindle.” The key thing is: many of these bets failed, and failure was expected. Failure isn’t desirable, but each bet had out-sized potential upside and budget-able downside. Even Kindle was unprofitable for years and the Amazon Fire Phone was an abject failure. Bezos explains in his own words that their strategy is exactly the theory of a portfolio of asymmetric bets with expected failures:

“If you’re going to take bold bets, they’re going to be experiments. And if they’re experiments you don’t know ahead of time if they’re going to work. Experiments are by their very nature prone to failure. But a few big successes compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work.”

“I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon.com. Literally. You have to be super clear about what kind of company you’re trying to build. … We said we were going to take big bets. We said we were going to fail.”

—Jeff Bezos, The Guardian, 2014

Futuristic

The best time to plant a tree is one hundred years ago. The second-best time to plant a tree is today.

—A proverb claimed by many peoples, across thousands of years

“Being agile”4 is a great way to climb the proverbial mountain-shrouded-in-fog. Some paths are the right ones, but backtracking is inevitable; it’s a sign of puzzling-out, not a sign of failure. The job of strategy is to identify which mountain we’re trying to climb in the first place—the puzzle we’re solving for, the opportunity we’re exploiting. If an “agile, self-managed” team climbs the wrong mountain, it was all a waste.

4 Meaning: Don’t pretend you can predict the future, assume the quantity of “things we don’t know” is larger than the quantity “things we do know,” iterate quickly on hypotheses that you proactively attempt to disprove, and adjust in the presence of new information. The team that learns the fastest, wins. The team that spends three months trying predict the future, is now three months behind, and the future still won’t unfold as they predicted.

Strategy looks further into the future than anything else at the company. Therefore, it has the responsibility to take the long view. Which is especially difficult, as the future is unpredictable, and data tells you about the past, but rarely about the future.

If you can solve a problem in a month, you probably should, but that also means it’s not a strategic problem. Anything that can be built in three months, isn’t the way you will have constructed a moat that will take competitors years to overcome. Anything that specifies features or timelines is a roadmap, not a strategy; a strategy specifies market and business outcomes and the primary decisions and secondary consequences. Anything that specifies teams or roles or hiring or processes is an operational plan, not a strategy; a strategy details the outcomes and activities that require the entire company to accomplish together, not what one team needs to accomplish alone.

People naturally get distracted by the immediate, the urgent, the tactical, the “low-hanging fruit.” Strategy is the place where we select the high-hanging fruit, the “important, but not urgent” quadrant of the Eisenhower Matrix. Then executed as the Rocks in your “Rocks, Pebbles, Sand” prioritization framework.

Part of explaining “how to win” is defining what the “winning” state looks like. Often called the “vision statement,” it describes what the world will look like when we’re successful:

| Oxfam | A just world without poverty |

| Habitat for Humanity | A world where everyone has a decent place to live |

| Stripe | Increase the GDP of the Internet |

| Microsoft (years ago) |

A computer on every desk and in every home |

| Tesla (original) |

Create the most compelling car company of the 21st century by driving the world’s transition to electric vehicles |

| WP Engine | Power the freedom to create online |

| YouTube | Give everyone a voice and show them the world |

| GoDaddy | Radically shift the global economy toward independent entrepreneurial ventures |

The Vision statement is often the first sentence the strategy document, but was the last thing crafted by the authors of that document. Only once you fully understand the challenges you face, the main, coherent courses of actions to undertake, and the results you want, can you summarize a clear vision of what the future will be.

Because words like “mission” and “vision”have indefinite meaning and are often misused, I prefer alternate words and intentions, as described in the article just linked.

Strategy is where we specify the most critical long-term challenges facing the company, and the rocks that are the most important things, not to win the battles today, but to determine how we will have won the war three years from now, how we will achieve our vision, how we will win.

Example: After Google purchased YouTube, they set a far-future goal of attaining a billion daily views. This filtered down to everything from demands on technical architecture, to strategic debates such as whether that enormous quantity of views could be achieved by user-generated content alone or whether they needed to license libraries of existing TV shows and movies. At one point they realized that the global Internet network infrastructure did not have enough capacity to stream a billion views per day, so Google invested billions of dollars in fiber and data centers to prevent that from becoming a bottleneck—billion of dollars they would not have spent without a vision of the future that mandated that investment.

Bad Strategy

Tell-tale signs of a strategy that lacks these qualities:

- Not simple

- Pages of detail.5 Slides with more than 20 words. A litany of numbers without a narrative explaining what insights they create. No diagrams “painting the picture,” or diagrams with 20 boxes. Too many points for someone to recall from memory. Important concepts that aren’t summarized by a short phrase that people can use as a daily short-hand.

- Not candid

- Nothing where the future of the company hangs in the balance. Nothing that makes the reader say, “Oh wow, dang, what are we going to do about that!?” Nothing scary that demands action. No serious consequence if the directives aren’t followed. A reader who finishes the document and thinks, “We’re still ignoring the elephant in the room.”

- Not decisive

- No clear decisions that would cause us to “easily say ‘no’” to many otherwise excellent, reasonable ideas. Not obvious what we’re not doing. Non-specific target market (e.g. “for everyone”), target customer (e.g. “any [title]”), target jobs-to-be-done. Directives and headings using the word “and” to expand scope rather than limiting it. No negative-but-accepted consequences of the decisions. Decisions that conflict with each other. Decisions that don’t reinforce each other.

- Not leveraged

- Strategy would apply equally well to a competitor, or even to a business in another industry. Strategy doesn’t call out the special strengths and durable assets of the organization, or doesn’t explain how to apply them to win, especially how it will position against the competition. No obvious moats being constructed. No network of interlocking decisions that together makes the company special. Demanding that the organization overcome more than one or two major deficiencies.

- Not asymmetric

- Potential upsides aren’t at least 10x larger than costs. Linear cost/reward, or risk/reward. Not creating optionality in how each aspect can go right, leading to one thing that absolutely must work. A course of action that requires multiple different, difficult things to simultaneously go right, otherwise the whole strategy fails.

- Not futuristic

- Doesn’t describe a specific future destination of the company or product. A “vision” that describes what the company already does and already is, rather than how things will be different once we successfully execute our strategy. Doesn’t specify which moats are being created, and how. Specifies teams, products, timelines, or features. Deals with temporary challenges that can be solved in a quarter rather than long-term challenges that will take years to fully overcome. Describes how to win this year instead of in three years. Relies primarily on data to predict the future.

- Not strategy (bonus)

- Generic statements that would apply equally to nearly any company, even in a different field (e.g. grow faster, lower attrition, hire the best talent, delight customers, beat the competition). Aspirations about what we wish would happen, without specifying how it will happen. Financial goals rather than how to win competitive markets. Plans that are in someone’s head instead of written down and shared. Written documents that aren’t referenced when creating plans.

5 Detail is great, if it is attached as optional reading, expanding on a summary.

A sailboat always moves forward, but if you don’t decide on a specific destination, it will end up somewhere, but probably not where you wanted to be.

Time to decide how you will win.

Postscript: How do I construct a strategy?

Stay tuned for future articles that lay out a process for constructing a great strategy. Partial answers appear in The roadmap for Product/Market Fit and Excuse me, is there a problem?.

But don’t wait. A mediocre strategy is still better than no strategy.

Further reading

- Article: WTF is Strategy? by Vince Law: Defining the nested concepts of vision, mission, strategy, roadmap, and execution, thereby contextualizing the role of “strategy.”

- Book: Good Strategy, Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt: Doesn’t explain how to construct a strategy, but terrific observations about what good and bad strategy looks like. ( Summary by Jeff Zych)

- Book: Blue Ocean Strategy by W. Chan Kim & Renée Mauborgne: Explains how to construct a strategy that is not only “different from the competition” (i.e. competes better in so-called “red-ocean” force competitive markets) but competes in a wholly different way, creating a new value-proposition, often at higher profit, in so-called “blue oceans” where you’ve defined yourself such that there isn’t any direct competition.

- Article: Gibson Biddle’s multi-part series on how to build a product strategy that converts “how to win” into “what to do”

- Article: Taylor Pearson on optionality, and how to apply the Nassim Taleb quote in practice, even personally.

- Article: Excuse me, is there a problem? on selecting the right “problem to solve” and “for whom” to increase the probability of success.

- Article: Using the Needs Stack for competitive strategy on thinking about customer value, markets, competitors, and disruption.

- Article: When customers are “willing” to pay on how to create strategies that capture and keep customers as your allies, who help you grow and find new customers, rather than forcing them to stay through coercion.

- Journal article: The Design School: Reconsideration of the Basic Premises of Strategic Management by Henry Mintzberg, Strategic Management Journal (1990), with a summary of traditional strategy construction, a critique of its drawbacks, and conditions when it is appropriate.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/great-strategy/

© 2007-2025 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear Simple eReader (Kindle)

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF