Pivot Points

Gallup® StrengthsFinder® is one of those registered® trademark® bedazzled® personality tests claiming to be uniquely insightful, honed over decades of scientific validation, in contrast to all those other personality tests who only claim to be data-backed, but are actually horoscopes recast in corporate lingo, that are thinly veiled excuses for consultants to charge you for assessments.

Oh, by the way, your Official® Gallup® StrengthsFinder® Assessment® costs $59.99.

But OK, for years at WP Engine every new employee takes the StrengthsFinder® assessment as they on-board, and they’re treated to their “Top 5 Strengths”. We’ve done it thousands of times, and people like it. I like it too, to be fair. It’s fun to feel important enough to warrant analysis.

My third-strongest strength is “Competitive”, which means what you think it means: I always want to win.1 Specifically, I want to beat other people in order to win.2

1 The part of Capitalism that is good.

2 The part of Capitalism that is bad.

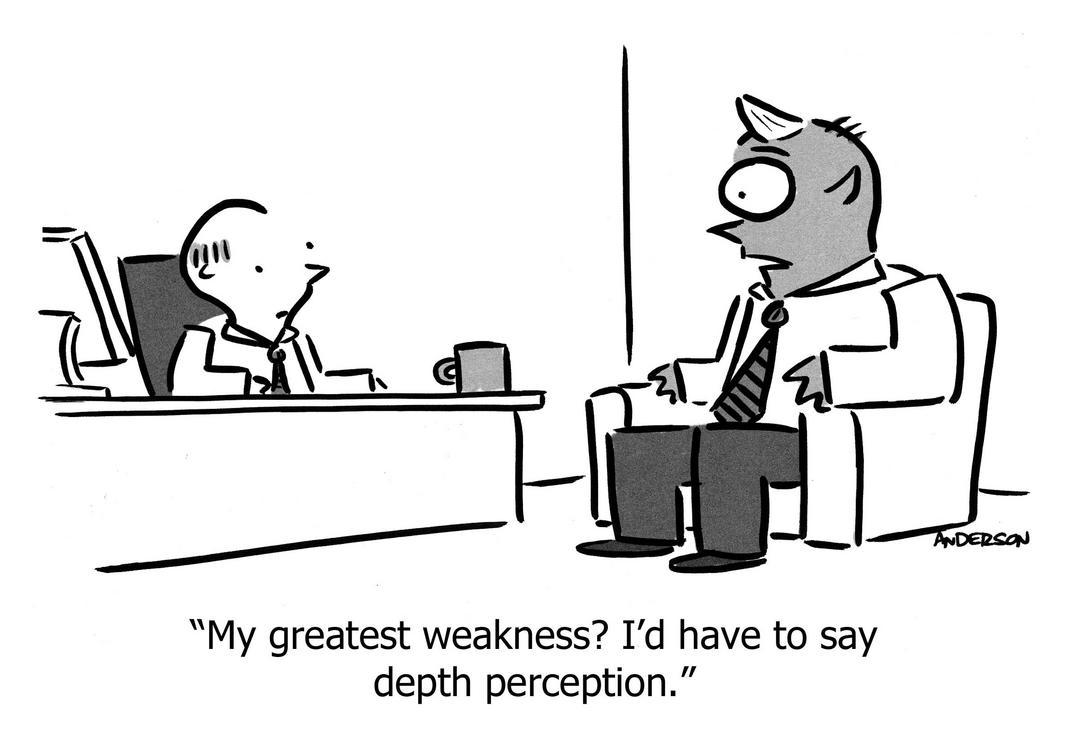

Is “Competitive” a strength though?

Yes, if I’m in a sales call. Yes, if I’m the last interview for a candidate who has other offers. Yes, if the person I’m trying to beat is “my past self,” generating motivation to become a better version of myself without overflowing into feeling that I’m unworthy.

No, if I’m in a team meeting where the goal is to help each other rather than to win the argument. No, if it sucks the joy out of games and hobbies. No, if I base my self-worth on (my false perception of) other people’s accomplishments.

So if it’s unclear whether it’s a “strength,” what is it, exactly?

The right analysis: Pivot Points

“Competitive” is a fact-of-the-matter of my personality. It’s a thing that exists, outside of judgment. I call this non-judgmental fact a Pivot Point because of how you can use them to win at life and business. The rest of this article explains how to do that.

Pivot Points are strengths in some situations, hindrances in others, and irrelevant in still others. This is why I don’t like the ideas of “strengths” and “weaknesses” generally—whether in personality tests or SWOTs or other tools of strategy and planning. Those frameworks imply that we already know the context for evaluation, but often we don’t. Pivot Points are neither intrinsically good nor bad, they just are.

But why the word “Pivot”?

Because you’re “stuck there” like your “pivot foot” in games like basketball and lacrosse and Ultimate Frisbee. Your other foot—and the rest of your body—is free to move anywhere, subject to that constraint. So Pivot Points are the constraints you build around. For example if you hate managing people (Pivot Point), you shouldn’t become a manager, nor should you make a company that will eventually require a team; alternatively, you shouldn’t be the CEO of that company.

The other reason is that Pivot Points can change, but not often, and not capriciously. Sometimes you pick up your foot, run somewhere else, and establish a new pivot; this is investing in a new skill, or learning a new industry, or overcoming something that’s a weakness relative to your goals. Short-term planning should assume Pivot Points are fixed, because in the short term, they are. Long-term planning, especially when deciding where to investing your time and money, can ask: What new Pivot Points do we want?

This also neatly matches the “pivot” concept from Lean Startup: When a company realizes that one aspect of the business is fatally broken, yet other aspects are insightfully correct. You don’t throw everything away; you’re realizing which things are correct or immutable—a.k.a. Pivot Points—and then pivoting the rest of the company around those things.

So let’s see how to find your personal Pivot Points (for your life), as well as those of your company (for strategy), and then how to exploit them to win.

Finding your personal Pivot Points

“Know thyself!”3 We ought to know ourselves, but we’re too close to the problem. You’re biased, you can’t get outside your own head, you have baggage, and few of us are naturally talented at honest introspection.

3 Inscribed at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, independently opined by many people throughout history, Thales gave this as the answer to the question: What is the most difficult thing? When asked what is the easiest thing, he answered: To give advice. Which is what I do in these articles. The truth hurts!

What drives you

These prompts will help you uncover who you are.

- Even when I was a kid, I would ______, and I still find myself drawn to it.

- Lately, I love it whenever ______ (which would surprise my ten-years-ago self).

- If I could go back in time, I would tell myself to worry less about ______ and more about ______.

- When I’m on an extended vacation, I get itchy to ______; I just can’t help it.

- My parents/friends always laugh when I start talking about ______ because I get so excited I can’t stop talking about it.

- My parents always said I would be a ______ because even when I was just six years old…

- Whenever I ______, I get lost in the work, and feel energized (not exhausted!) when the work ends.

- If I could go (back) to college, I would get a degree in ______.

- The last project I really enjoyed, and wish I could keep working on, was ______.

- I was surprised how much my peers praised my work when I ______; maybe I’m better at that than I thought.

- Recently I was totally immersed, engaged, excited, and happy while doing ______.

- I asked a few people who know me, and who I trust to be thoughtful and observant, and they said my special strengths are ______.

What hinders you

Sometimes it’s easier to avoid something you hate, then to construct a situation where you’re constantly doing something you love (always invert):

- When I’m faced with ______ I physically feel the “pit of my stomach” falling.

- The last time I had to ______, I did an embarrassingly minimal job, because I couldn’t bring myself to do better.

- I have an intense dread of any meeting where we ______.

- If my job starts requiring me to ______ with even 10% of my time, I would at least think about changing jobs.

- When I’m faced with ______ I procrastinate so much, I do chores that I dislike and normally avoid.

- If I’m being honest, although I would really love to be great at ______, the fact is I’m just never going to be good at it.

- Whenever I ______ all day long, I know I do great work, but I’m absolutely exhausted; the rest of the night will be vegging out of the sofa with mindless entertainment.

- I know I’m supposed to like / do ______, but the truth is I never get excited about it.

You should be honest, even if you think “society” doesn’t like your answers. There’s nothing wrong with the drive to make money, or to become famous, or to prove a point.

Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen—in short, with the whole top crust of humanity.

—George Orwell, Why I Write

Outside-in

Ask other people about your strengths and weaknesses—yes, that language, because it helps others generate answers, even though you’re going to untwist their observations into non-judgmental Pivot Points. Unfortunately they’re rarely fully honest, even when anonymous.

My favorite reference-check interview question can help. Candidates refer you to friendlies who are primed to say nice things, so there’s no value in their sanitized recommendations. Instead, I ask the following:

What is the ideal scenario, under which this person thrives?

That is: Construct the absolutely perfect set of circumstances—subject matter, goal, team (or lack thereof), direction (or lack thereof), incentives, etc.—where this person absolutely kills it, is efficient, is productive, is extremely happy, and makes everyone around them happy.

The answer generates Pivot Points. If they say “Oh yeah, you need to give them a goal because they want to know what ‘success’ looks like, but then get out of their way because they’re really creative and they explore quickly and you don’t want to squash that,” then you extract Pivot Points like “goal-oriented” and “craves exploration”. That means working in an R&D group might be a bad fit (not goal-oriented), as would working on a mature product (needs execution, not exploration), but an early-stage startup would be great (clear goal, and exploration is mandatory and valued).

Also ask the opposite:

Construct the scenario where they die inside, mess everything up, and piss everyone off.

It’s funny to ask it and easy for them to answer, but doesn’t feel like you’re being negative about the person; after all, we all have a personal hell. More Pivot Points.

Another great question to ask others:

What are my strengths that I’m unaware of because they come so naturally to me? Where I don’t realize other people aren’t like that too?

These are our most natural, powerful Pivot Points, because we can’t help but be great at it, and yet they are special. These constitute your “edge.” Definitionally you can’t see them yourself, because you don’t realize how special they are. Ask others.

It’s not easy to know yourself, and “yourself” changes over time. But it’s worthwhile to identify major Pivot Points, because pivoting around them (or deciding when and where to invest in altering them) is how you construct a fulfilling life.

Now we’ll do this for a product or company.

Finding your Company’s Pivot Points

“Knowing thyself” is hard enough for an individual; collectively we’re even more complex, and each person holds different knowledge about different areas. We can’t ask our team to just “write down what we are like.” Here’s what to do.

Suppose you knew nothing about the inner workings of your business. Pretend you are an outside consultant, hired to reverse-engineer every aspect—not what the people inside the business think it is like, think are its strengths and weaknesses, but what’s actually going on. You’ll be sussing out the decisions that led to their strategy, even if they never consciously made those decisions or wrote down that strategy. You job is to write down “what is.”

You’re allowed to observe behaviors and results, but not allowed to interrogate people to understand why they took those actions. Indeed, it’s important that you don’t interview people, because they will unwittingly rationalize, or even mount a defense. We’re discovering, not judging.

The generative procedure starts with write-storming4 observations about what is special or peculiar about the product and company.

4 Write-storming is brainstorming in which participants write ideas in isolation, then bring them together for deduplication and enhancement. This eliminates the bias towards the fastest, loudest voice, supports people whose brains need more time to ponder, takes advantage of background-processing (i.e. “I thought of something in the shower”), and more fully includes non-native speakers who will be much more precise and compelling when given time to translate. “I was shocked to find there’s not a single published study in which a face-to-face brainstorming group outperforms a [write-storming] group”—Leigh Thompson, Creative Conspiracy. Also, recent research suggests that people are less creative in generating ideas over video-conferencing versus in-person, but there is no such difference in the quality of selecting good ideas from a list. Therefore, the optimal process appears to be write-storming to maximize creativity, then meeting up for synthesizing.

Precipitation

You can’t ask people to list “things about us that are special and important”—it’s too vague, and won’t be comprehensive. Instead use specific, evocative prompts:

- Undeniable comparative strength

- What specific things are customers buying, when they choose us despite our many foibles? What does our company do so well, even the competition admits it during their own sales calls, because otherwise they’d lose credibility? What is our team capable of, that most other teams are not?

(Whether it is difficult for others to copy or not, whether customers or competitors seem to care about it or not.) - Consistent complaint

- What complaints do our customers have, that we’ve heard so many times in so many channels that we don’t even need data to know it is true? On what point does a competitor instantly win, because we have no defense against that claim? What is so problematic that people leave us for this reason alone, even when they’re otherwise happy, even when they rate us 10/10 on NPS and apologize as they cancel?

(Whether it’s smart for us to react or not, whether it’s intrinsic to our product or relative to a competitor.) - Customers advocate for

- When our customers brag about us on social media or in private meetings, when it’s genuine advocacy, what do they highlight? What positives do even disgruntled employees begrudgingly admit on Glassdoor? What concessions do one-star reviewers make?

(Whether we think they’re exaggerating or not, whether it’s what the majority of customers would agree with or not, even if the NPS-0 customers disagree, even if customers in their exit interviews disagree.) - Best customers

- What are the characteristics of our best customers: The ones who pay the most, never call tech support, score 10/10 on NPS, never leave us, upgrade consistently, advocate for us externally. More specifically: What characteristics are prevalent that aren’t shared by other customers?

(Whether that’s a large market or not, whether it’s shared by only 30% of them, so long as it’s shared by <10% of the rest of the population.) - Proud of

- What about our product or team are we especially proud of, whether because we consider it to be great workmanship, or because it reflects “who we are,” or because it was difficult to do, or because it’s just fun? Or the opposite: What do you absolutely hate that some other company does?

(Whether customers agree or not, whether there’s data to support that feeling or not, whether it’s a competitive advantage or not.) - Talking & Walking

- We say we’re great at certain things on our website and sales material. How much of that is true? What else are we great at, that we don’t brag about? We say certain things because we know that our customers desire that quality, and we at aspire to be great at it. Use the Talk/Walk Framework.

(Whether or not this directly harms sales or retention.) - Clear and present existential threats

- What is either happening now, or has at least a 70% chance of happening in the next few years, which would seriously disrupt our business? Something that would dramatically tank sales, where customers might start cancelling in droves, maybe even end the entire business.

(Whether there’s anything we can do about it or not, whether it’s our own fault or not. But hold to the “70%-100% chance” requirement so that there’s few if any; otherwise, every company has twenty theoretical disaster scenarios.) - Structural attributes

- What does our technical architecture or human organizational structure specifically make possible, easy, or natural? Or the opposite: unstable, manual, too difficult, unscalable?

(Whether we think that’s a “good thing” or not, whether competitors are similar in that respect or not.) - Philosophy & Values

- Things you believe in so much, you’ll honor them even if it loses you customers, even if it loses you money, even if it slows you down, even if you have to fire people because of it. Because this is who you are. What do you believe in your gut, about what it means to do great work, what kind of organization you want to build, what impact you want to make in the world. Example: Is “great design” absolutely critical for success, at least the kind of success you want to be a part of, or is “design” overrated, nice-to-have but a functional product and superior sales will beat it every time? Example: Is “ship fast with bugs” the best policy, because you learn the fastest and therefore get to the truth and product/market fit the fastest, or is “ship fewer things with high quality” the best policy, because you win lifelong loyal customers with craftsmanship and care, not by exploiting them as unwitting lab rats?

(Whether lots of other people agree or not, whether there are lots of successful examples to point to or not, whether this is the “in vogue” thing to believe or not.) - Great ideas

- What ideas keep recurring, typically because of an ingrained sense of conviction stemming from one of the areas above, i.e. we would be proud of it, we think it would become a comparative strength, we think customers would become advocates because of it.

(Whether customers are actually asking for it or not, whether or not we have objective evidence that it really is a great idea.)

Condensation

You’ll find this exercise unearths all sorts of things you can act on. For our current purpose, we distill them into fewer, clearer Pivot Points.

You do that with the following workshop:

- Rotate through observations

Go around the room, asking each person for just one of their better observations. We’ll get to all of their ideas, so don’t stress about which one is “best,” just pick a good one.5 Together the group processes one observation at a time. - Clarify

Everyone asks clarifying questions—not arguments—to ensure we understand “what it is.” Boil it down to a few words so it can go on the board (which is a whiteboard, or Miro, or whatever you like). Use one color for the observations. - Convert to Pivot Points

The group asks: What Pivot Point does this translate into? For example, “Customers post screenshots on Twitter of long wait-times in tech support” becomes “Slow tech support.” Or “Customers brag about us by posting side-by-side screenshots of our product next to a competitor” might become “Delightful, remarkable design.” Write the Pivot Points in their own color, and place the observation next to it. Themes will emerge as some Pivot Points will accrete many validating observations. And the other direction: if there are multiple target Pivot Points for a single observation, duplicate the observation card. - Don’t evaluate; don’t act

It’s tempting to jump to a conclusion like “Slow support means we should hire more people,” but fast support might not be of strategic importance, so maybe you should deemphasize support from marketing and sales materials instead of “fixing it.” And even if you decide you do need to fix it, should you really hire more people, or should you instead write better documentation, start using AI support chatbots, switch from tickets to chat, improve the UX of the product to prevent common questions, change what segment of the market you’re marketing to, or what? “Now” is not the time to answer that question. - Merge Pivot Points as you go

It’s better to have fewer, stronger Pivot Points. A smaller set is easier to hold in mind, easier to act on, easier to set in stone. But beware the trap where you make them so general that they cease to be useful. For example, “We love our customers” is too generic. Use the Opposite Test to make sure you haven’t gone over the line. When in doubt, don’t merge; being specific and actionable is more important than quantity. And definitely do not have a target quantity like 3 or 10. There are as many as there are. - Loop until exhaustion

As you repeat the loop around the room, you start to skip people who are out of items, until everyone’s list is exhausted (and so are they).6

5 This is a facilitation trick I learned from Jonathan Slain. It ensures everyone gets time and attention, not dominated by the person who jumped at the chance to go first and unload dozens of items.

6 The process moves slowly at first, as people get used to the system and talk too much about each item. People will look at how many more items remain on their own list, and will worry this will take eight hours to complete. But it never does; you accelerate naturally (or the facilitator can start pressing for brevity), and people realize some of their items aren’t that important relative to what’s already up there, or are duplicative, and suddenly it’s all finished.

The process will throw off lots of ideas, follow-ups, and potential actions. Collect those during the process, and visibly write them down elsewhere so people know their ideas aren’t lost. But stay on-task.

Applying Pivot Points

Great strategy and a fulfilling life starts with honoring Pivot Points as facts-of-the-matter that you construct strategies and careers around. There are articles on this site about how to do that, and there will be more in future.

Here’s some direct ways you can use Pivot Points create better product strategies and a better life:

- How does our current strategy, or a proposed strategy, map to our Pivot Points? Where is it reinforced (therefore we should go deeper) or contradictory (therefore we should pivot)?

- How do we do even more things that leverage multiple Pivot Points? When we do that, not only are we perfectly suited to it, they are automatically differentiating in the competitive market, because others would have trouble copying us, because their Pivot Points are different from ours.

- What changes to our strategy would design around the negative consequences of our Pivot Points, so we’re not in our own way, or playing a game that others are better suited to win?

- Given the Pivot Points we identified, what additional ones must also be true, either as a downstream consequence, or because any self-consistent strategy would have to include them? Add those to the list. Yes this is recursive and it’s turtles all the way down; that’s what a “self-consistent, mutually-reinforcing” strategy looks like.

- Is there a singular concept leveraging/avoiding multiple Pivot Points, around which we could build our entire positioning and strategy?

- What type of customer—demographic, firmographic, job-to-be-done, budget-size, location—would find our Pivot Points refreshing and attractive? Is that our current ICP, or how should we adjust it?

- Are we making promises we can’t keep? Are there promises we should be making because we’ll naturally win there? In short: Does our marketing match our behavior, and what level of the Needs Stack should we be operating at?

- Are there contradictions in our Pivot Points? For example, do we want to deliver “Instant 24/7 support” but also “Can work only 4 hours/day” because of a day job and a family? Some contradictions must be resolved by changing the Pivot Points, but sometimes we can synthesize new ideas that make everything work after all; these are often our most valuable and differentiating ideas. Here’s how to navigate balance vs choice vs synthesis.

- What if one of our Pivot Points are wrong, i.e. it’s not the truth? Can we challenge each one, making sure we know it is true? If it weren’t true, what else would change? Should we actually make that change?

Here are specific examples of how younger startups can defeat large incumbents, when the startup leverages their own Pivot Points while designing around the Pivot Points of the incumbent. And how those same Pivot Points are different with AI.

In my case, being Competitive lends itself to entering a large, existing market with stagnant competitors, with a strategy of “build a 10x better product and then win in marketing and sales.” On the other hand, someone who hates the idea of having to “win” at “sales” could build a niche product, simple enough to explain and advertise that it doesn’t need a sales team, with a brand voice of a one-person boutique that makes a perfect, specialized product and IYKYK. Or someone who loves people (Pivot Point) but hates sales (Pivot Point) could start a consulting company where they forge long-lasting relationships with clients through on-going work like taking over an entire department of the company (e.g. marketing, support, engineering, or finance). All of these are wonderful strategies, so long as they match the founder’s Pivot Points, and the needs of the chosen market.

Some people call Pivot Points “ enabling constraints”. The theory is that constraints helpfully tame complexity, and then increase creativity. Which they do; one might say the definition of “design” is “art + constraint”.

I don’t like the “enabling constraint” phrase, however, because people get hung up on constraint. “Constraint” sounds limiting, and indeed it is, even if it also triggers new and better ideas. It’s not obvious how being “limited” is also “enabling”. Whereas, “Pivot Points” are facts with all manner of consequences, that we should leverage or design around.

Finally, although you can invest to change Pivot Points, beware. Some things might be too difficult to change. Some things might be too expensive to be worth changing. There’s a risk that the change isn’t successful. Change disrupts the organization. Sometimes employees get mad and leave. Sometimes customers get mad and leave. Sometimes people can’t change. Sometimes they shouldn’t.

Change Pivot Points only when the upside is so enormous, that even if you achieve only 30% of the transformation you were hoping for, it was still worthwhile. And don’t do too many at once. Maybe just one, whether for yourself, or the company.

As Tim Ferris describes it, when anyone asks whether they ought to write a book:

If the rewards are 1/4 of what you think they will be, and it takes 2x longer than you think it will take, is it still a no-brainer to do it? Not just “good” but a “no-brainer,” like you almost have to do it?

When you design a life or a strategy around Pivot Points, it’s magical. It means you’re “following your calling.” It means you’ll be more efficient, more effective, produce better quality, compete better against those who don’t share your Pivot Points, and have a lot more fun. It’s fun to do what you’re meant to be doing.

Life is short and companies are difficult. Don’t fight Pivot Points. Embrace them.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/pivot-points/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF