All pretty models are wrong, but some ugly models are useful

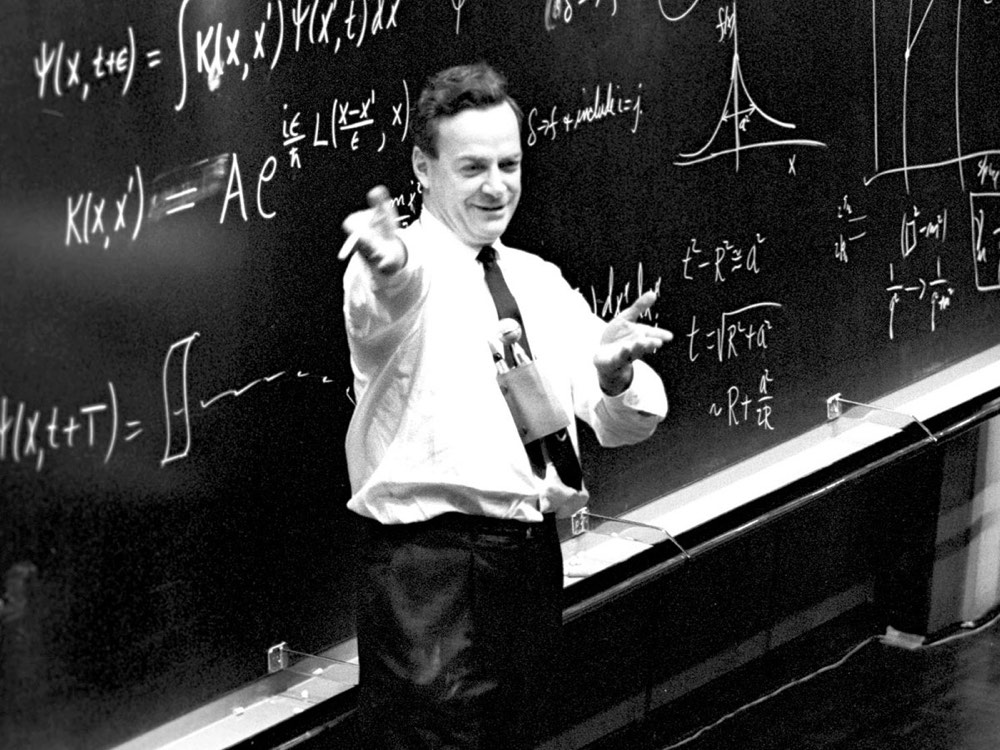

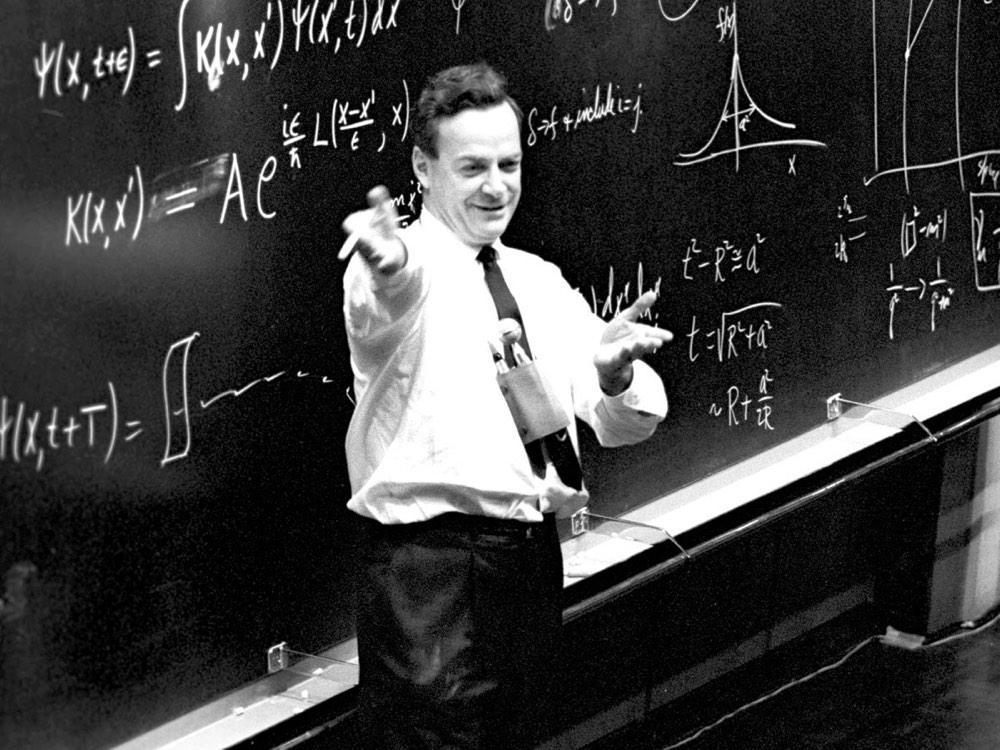

“Study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible!” —Richard Feynman

Wrong, but useful

Contrary to our intuition, a theory of physics can be useful—making accurate predictions—and yet simultaneously incorrect—not accurately describing how the universe actually works.

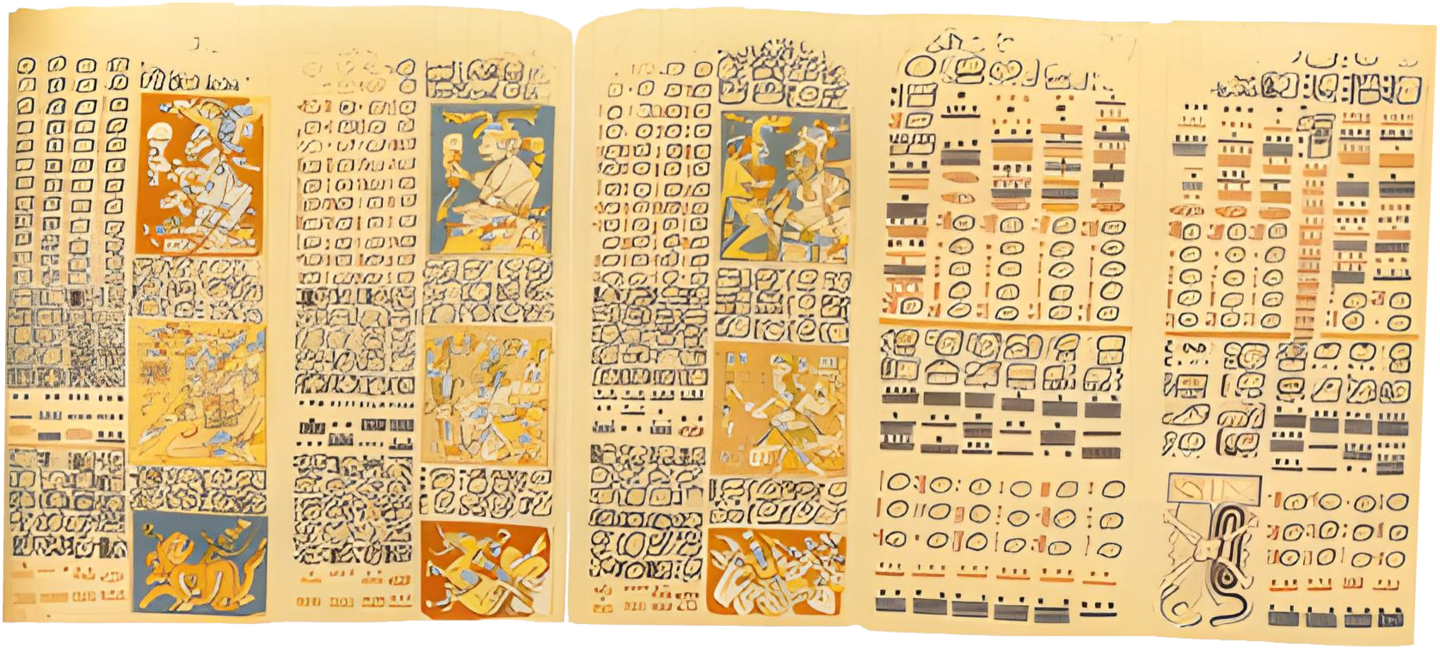

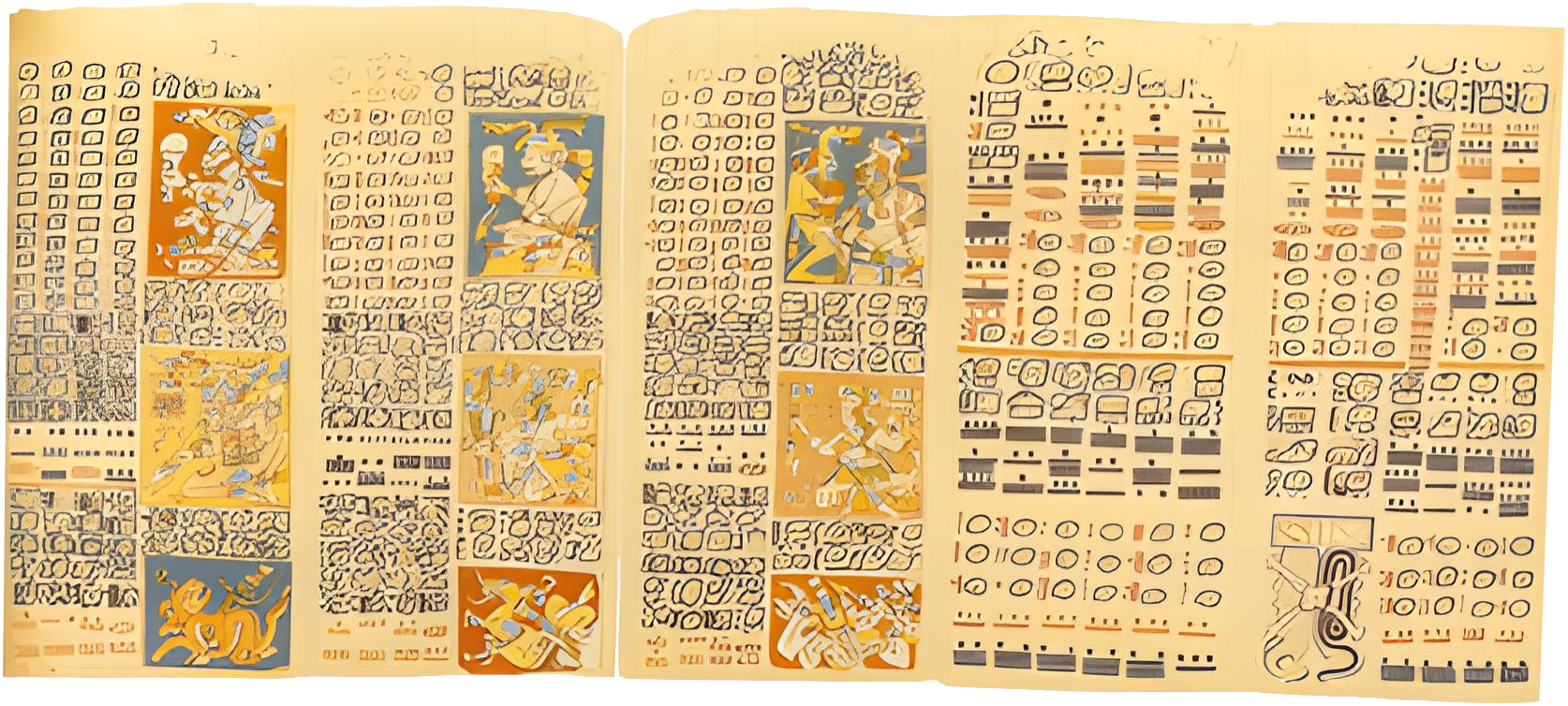

The Mayans’ conception of the Earth, moon, sun, planets, and stars, was as ludicrous as every other ancient civilization, yet their priests routinely predicted the timing of eclipses with impressive accuracy. The priests leveraged this accuracy as evidence that their religion was correct, and that their exalted position in society was justified.

Their religion—and therefore their explanation of how the universe worked—is laughable to the modern reader: The Earth in the center (of course), with thirteen tiers of heaven whirling above and nine levels of underworld threatening from below. Eclipses are not caused by a physical object blocking the light of the sun, but rather spiritual beings temporarily consuming the sun or moon (Figure 1). Even the most fervently religious person today would classify these ideas as fanciful mythology, though the Mayans were no less certain of the veracity of their religion than modern-day humans are of theirs.

Figure 1: Recolorized segment of the Dresden Codex, a Mayan text from around 1200 AD which, among other things, predicts eclipses to within a few days.

Nevertheless, they were careful observers and meticulous calculators. They understood that eclipses happened roughly every 173 days, adjusted by a 405-month cycle and additional smaller corrections. They tracked these cycles and updated their model over the centuries, and as a result their theory yielded accurate predictions, even though the theory’s explanation of why was entirely incorrect.

This is a striking example of the common bromide: All models are wrong, but some models are useful. Their model was wrong in describing the universe, but useful in predicting eclipses.

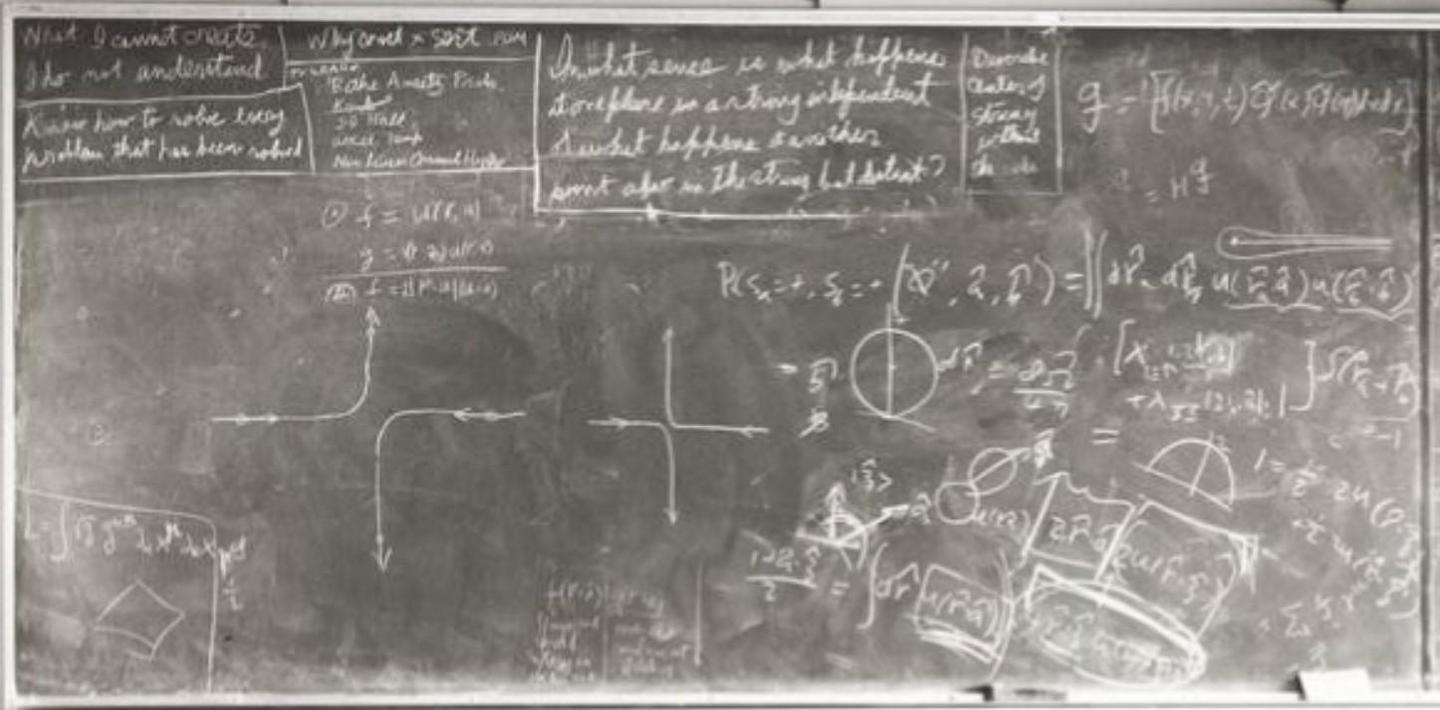

A thousand years later, modern physicists still wrestle with the question of whether their models explain how the universe actually works, or are merely useful. Physicist Richard Feynman illustrated this point using the Mayan example above. Quantum Mechanics (QM) is so weird and counter-intuitive, Feynman says, that “nobody understands quantum mechanics.”1 And this is from someone who won a Nobel Prize for creating an accurate and useful model for how some of it works.2

Feynman (jointly) won the prize for modeling how particles interact with each other. The model sounds as crazy as Mayan mythology: It says that all possible interactions happen simultaneously3 (yes, “everything, all the time”), with every interaction-possibility reinforcing or cancelling-out other possibilities, and with each interaction weighted by the probability of its occurrence. When we make a measurement in the lab, the cosmic dice are thrown, and one of those interactions is observed to have occurred in actual fact.

1 From The Character of Physical Law. This is sometimes erroneous quoted as: “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” That’s a cute paraphrase, but he didn’t postulate that someone would even believe they understood it!

2 Electrons and photons specifically, but it turns out to be the right model for all types of subatomic particles.

3 The precise description is: Sum the probability amplitudes and phases over all paths the particles could have taken, including an infinite hierarchy of virtual particle interactions. I ask the pedantic reader to forgive my evocative simplification.

This, of course, makes no sense. This sounds like Mayan cycles that miraculously spit out the correct answer, not how the universe could really work. Albert Einstein thought as much, famously trolling “God does not play dice with the universe.” To prove his point he, along with Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, described the “ EPR Paradox”—an experiment where the QM model predicts an even more “absurd, impossible” result, therefore (they felt) “proving” that the QM model is a more sophisticated kind of Mayan cycle computation, and might even be downright incorrect. Unfortunately for Einstein, physicists have run the EPR experiment many times in the subsequent decades, and the model-nobody-understands has always been correct in every detail.

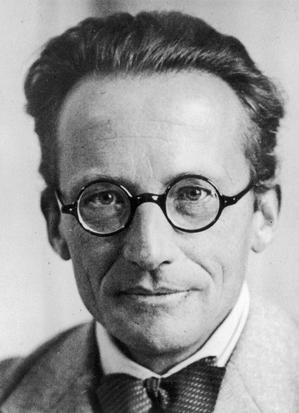

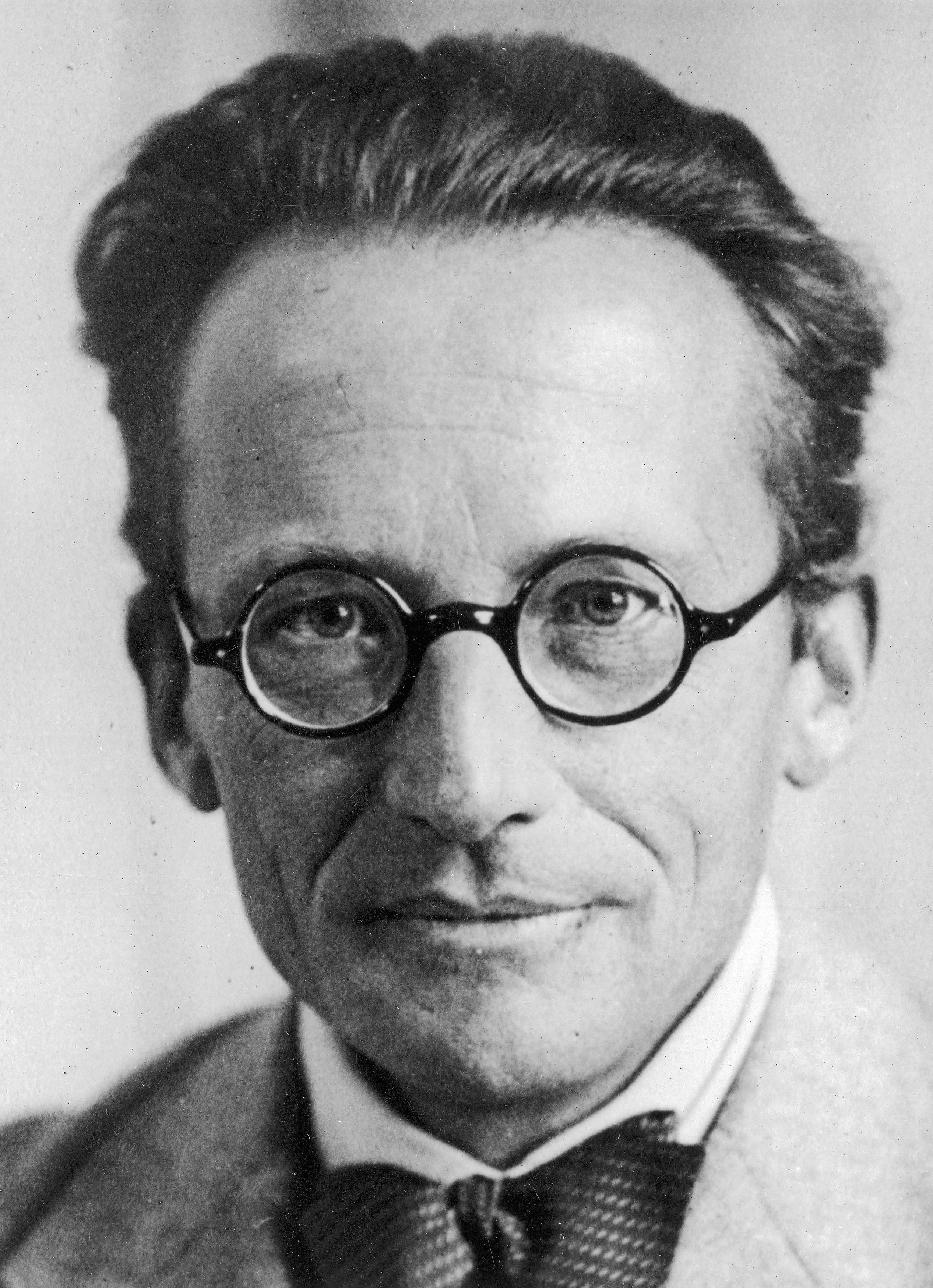

Erwin Schrödinger in 1933

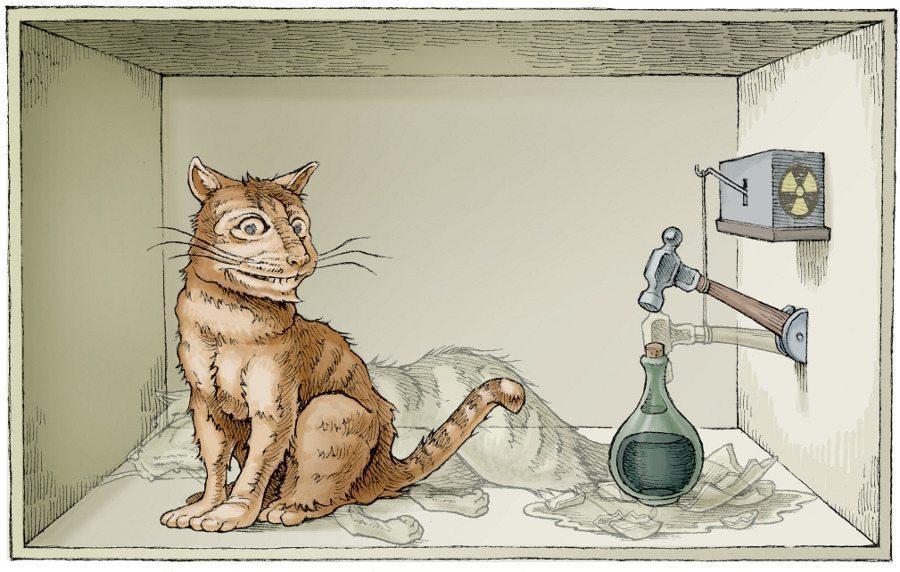

Erwin Schrödinger was also personally entangled with the apparent problem that the QM model was absurd, yet useful. His Schrödinger Equation is the center-piece of QM: It dictates how the entire universe evolves over time. Nearly every QM calculation runs through this equation. And yet, like Einstein, Schrödinger agreed that although the model is successful, its description of how the world works is ludicrous, quipping “I don’t like it, and I’m sorry I ever had anything to do with it.”4 He invented the famous Schrödinger’s Cat (Figure 2) thought-experiment to prove that QM must not be describing how the universe “actually” works, just as Einstein attempted with EPR. And, like Einstein, his attempt failed; physicists have run this experiment dozens of ways over nearly a hundred years, and the model has always been correct.

4 Here “it” refers specifically to the Copenhagen interpretation of the collapse of the wave function when an observer observes it; another facet of QM that obviously makes no sense as soon as you ask “What do you mean by ‘observer’ and why isn’t that just another physical system?”

Figure 2: The QM model says that Schrödinger’s cat is simultaneously alive and dead until you look inside the box; another example of “everything happens, but with probability, resolved when you observe it.” Both the “simultaneously” and “when you observe it” are nonsensical concepts (how does the cat-system “know” that some human-system “observed” it?), yet hundreds of experiments have confirmed the predictions of the model.

Beautiful, but wrong

And so we come to models of companies, markets, and people.

Economics, modeling how companies operate in isolated, simple paradigms (micro) or in bulk (macro). Management theory, modeling how information and control and human behavior flows across organizations. Strategy theory, modeling a company’s most important constraints and levers, strongest capabilities and assets, modeling competitors and the market at large, resulting in the top-level decisions that we hope will bring success. Product Management, modeling customers’ whims, incentives, “pain-points,” “delighters,” “JTBD,” and willingness-to-pay. Startup theory, giving frameworks for methodically transforming an idea into profit while avoiding failure.

All of these models work some of the time. All explain the past retroactively but often fail to predict the future, and thus none are on par with theories of physics, and arguably shouldn’t be called “theories” at all. A company is not an experiment with controlled variables and many trial-runs. Even using the term “expected value” is a fallacy.

Are these models more like the Mayans or more like QM? Are they occasionally useful but not representative of how the world actually works, or do they indeed model how the world operates, where their outputs are incorrect not because they are intrinsically flawed, but because of noisy environments, faulty inputs, missing inputs, or human operators who are more interested in selling consulting services off their own HBR articles and books than they are in acknowledging the limits of our simplistic models in the presence of an irreducibly complex world?

This is partly how I judge frameworks: Does the framework attempt to model the messy real world, or does it seem like a pretty fantasy that looks nice in presentations, HBR articles, and consultants’ sales materials?

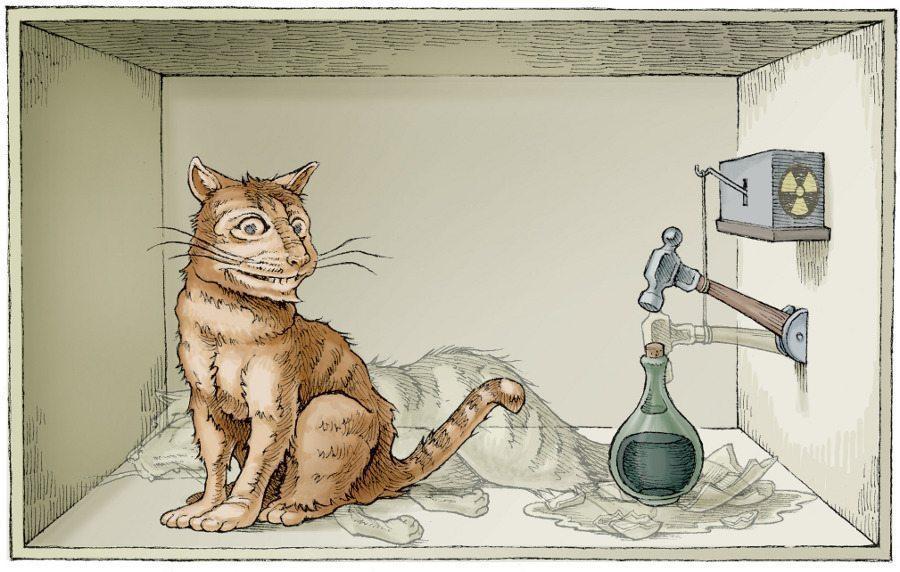

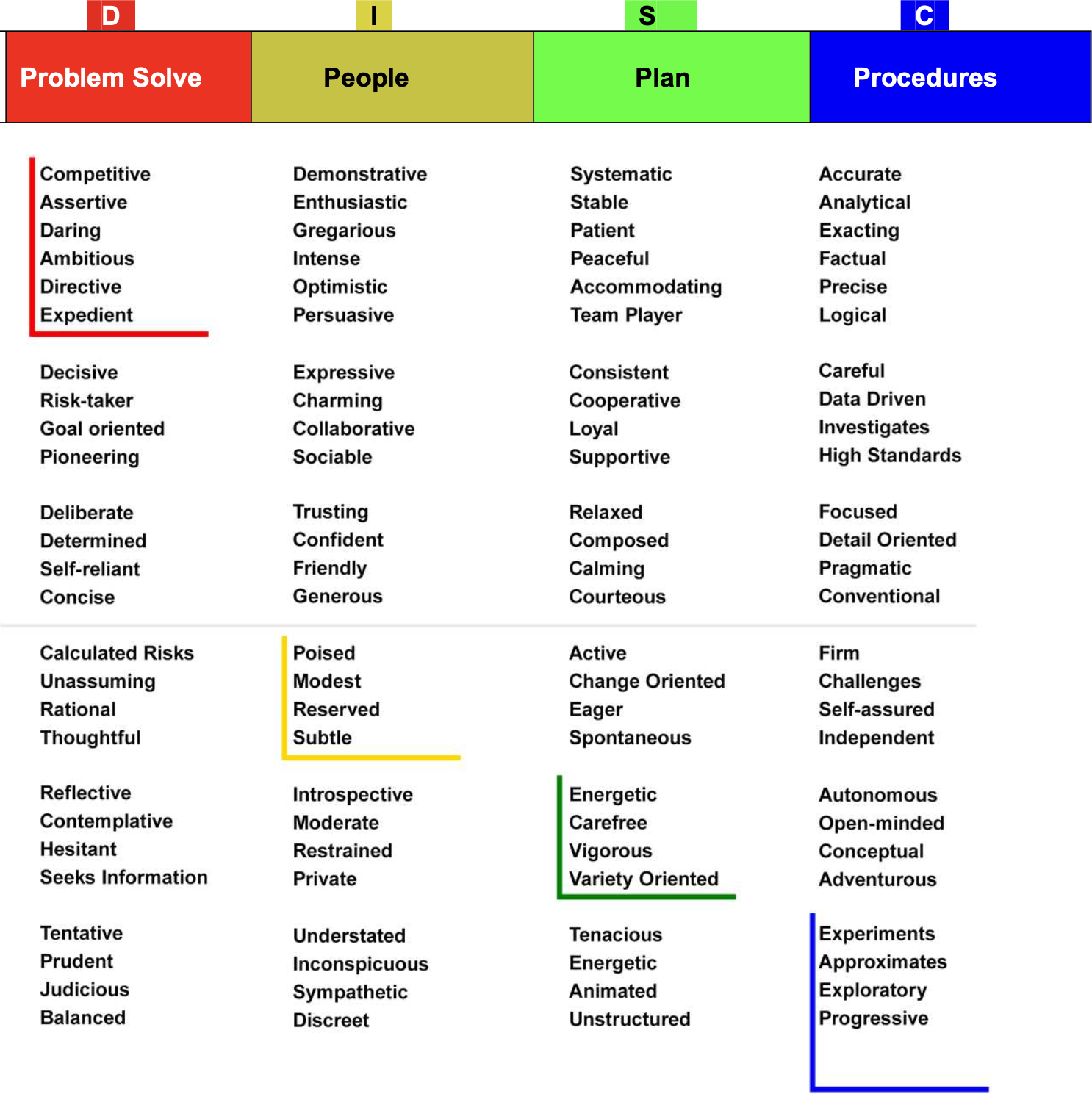

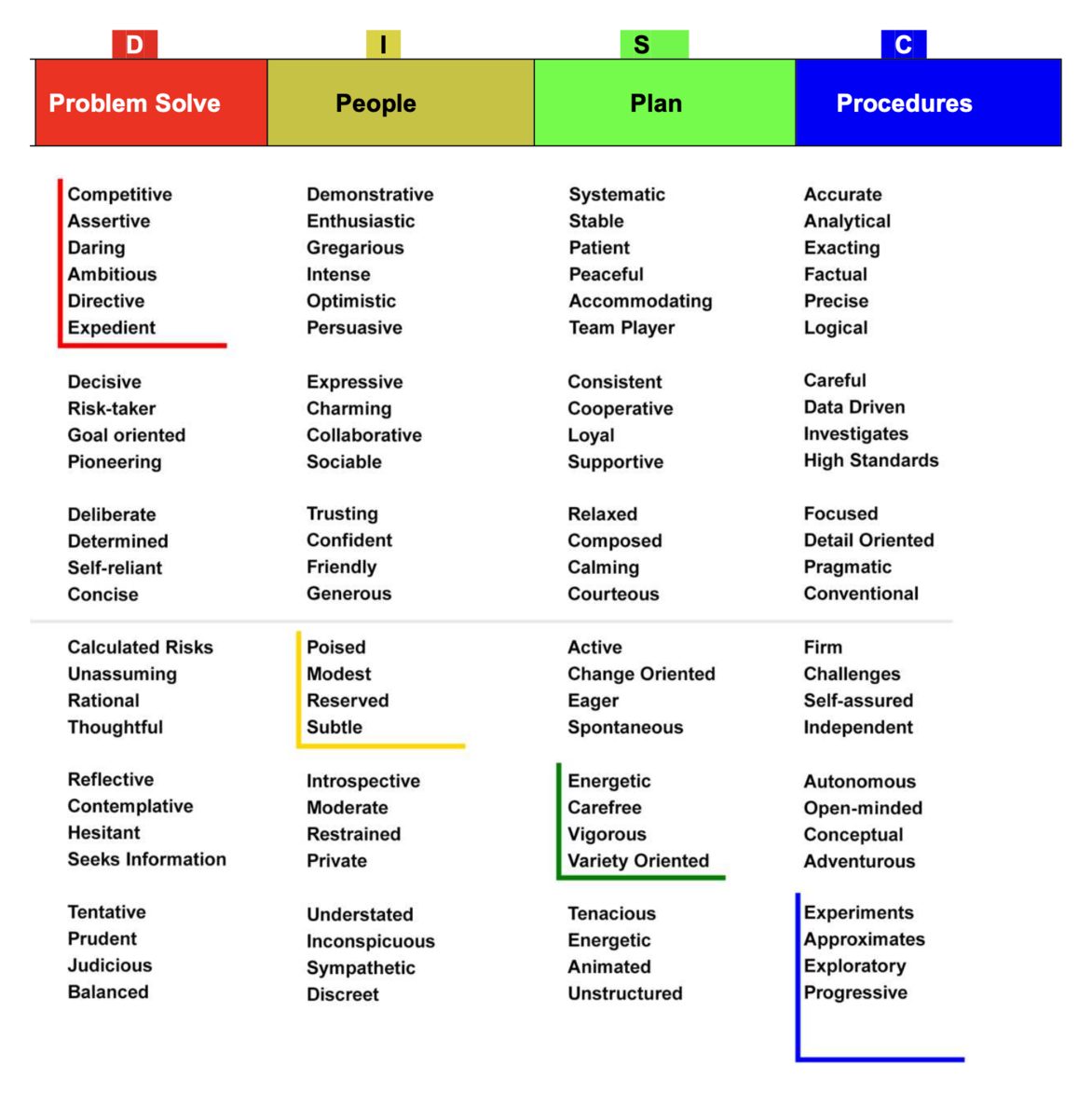

For example, I immediately disbelieve any framework about human beings that comes packaged in a nice, symmetric diagram, with identical quantities of bullets and sub-categories:

Figure 3: The DISC personality assessment

Human beings are more complex than saying “there are four categories, and each of the four have exactly six subcategories of descriptors, and each of those have an identical number of components.” No, that’s never how it is with people. If you had said there are five major categories, and some don’t subdivide, while others are complex, and some are fairly well-understood, while others are still a mystery, I’d believe that you were trying to model reality instead of ensuring some picture had 90° rotational symmetry.

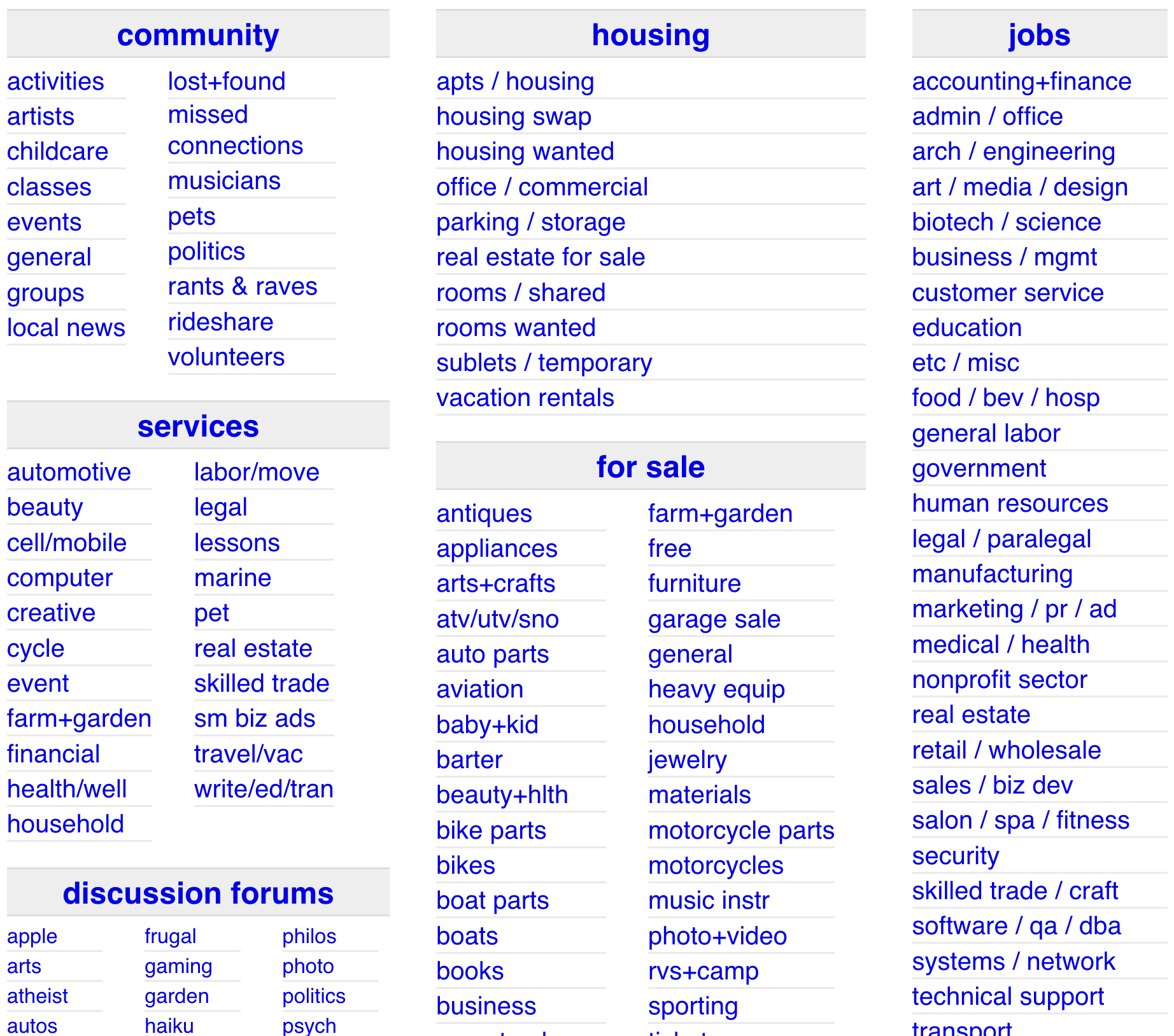

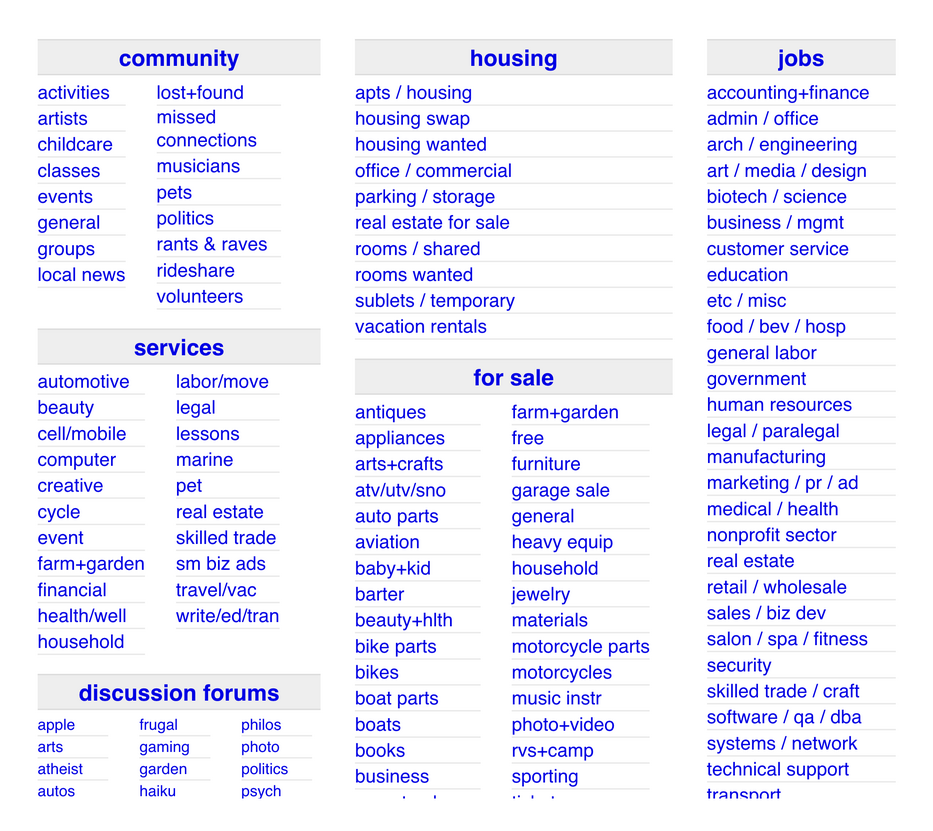

A more accurate model of human activity is seen in Craigslist, where they have “however many” categories containing “however many” subcategories:

Figure 4: Craigslist listings for Austin, TX

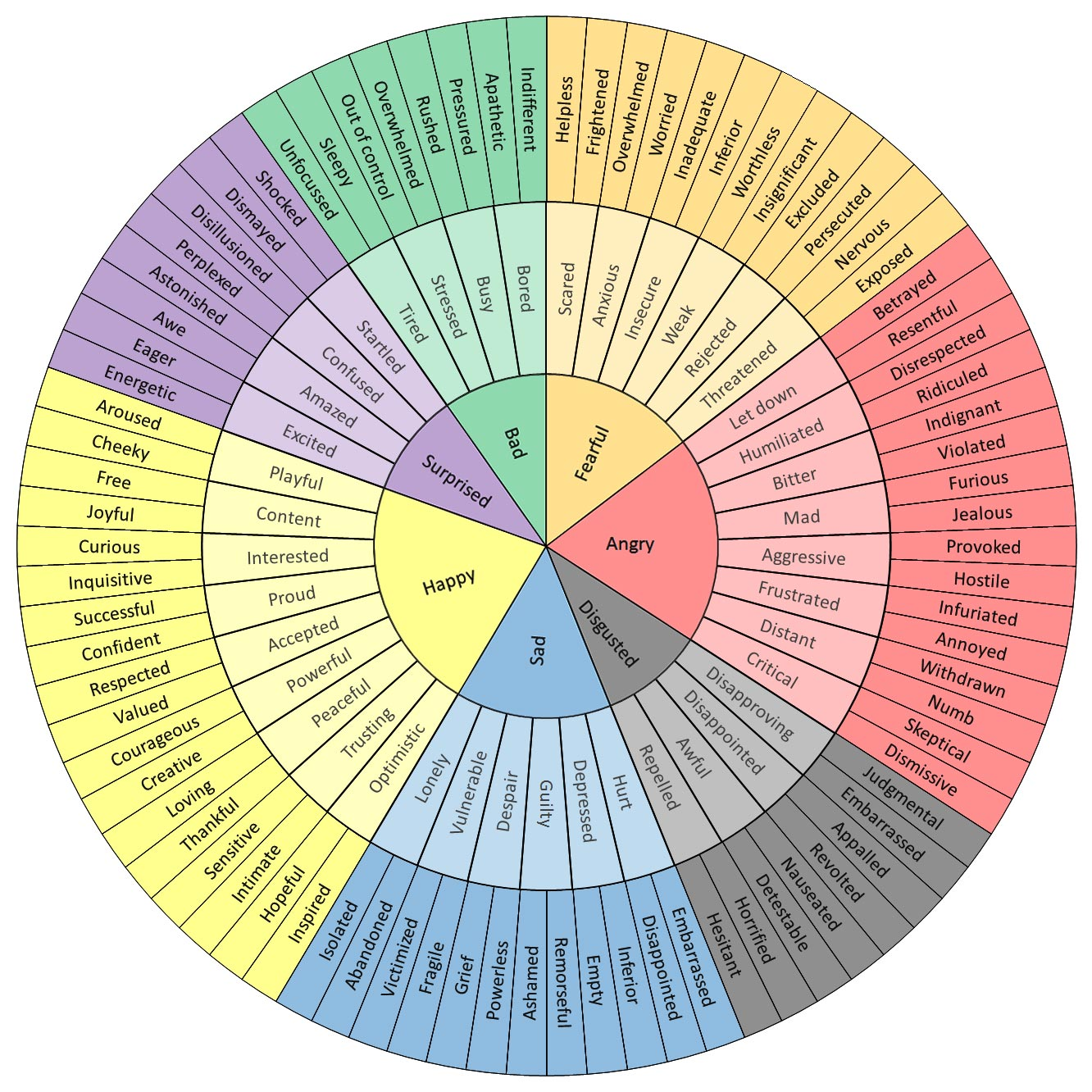

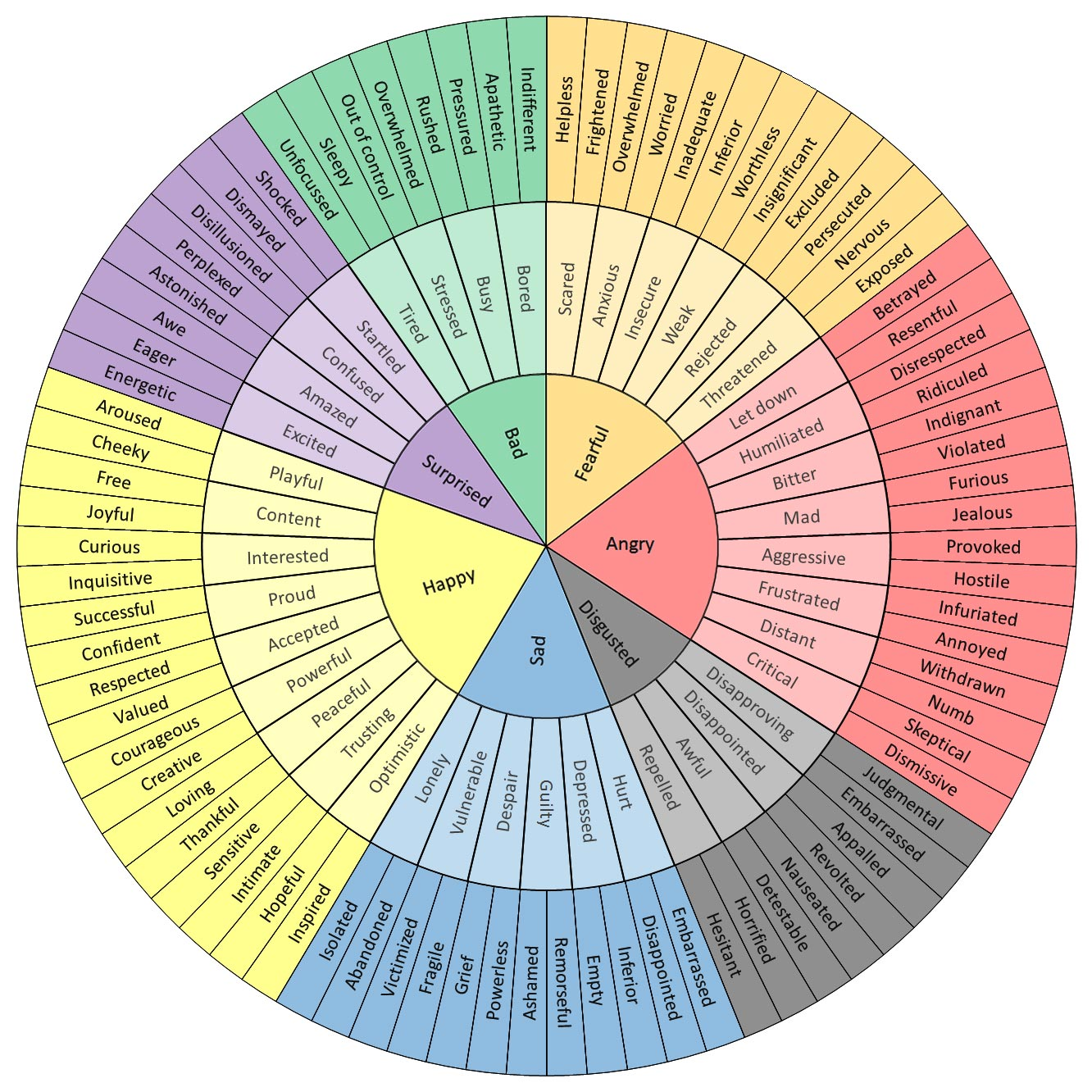

Human emotion had better not be modeled as a perfectly-symmetrical list. In 1980 Dr. Robert Plutchik created a better model, designed to help his patients identify their feelings—quite useful! It is suspicious in that every second-level category contains exactly two third-level emotions, but at least the first-level categories vary in quantity:

Figure 5: “Feelings Wheel”

Plutchik, Robert. “A General Psychoevolutionary Theory of Emotion.” Theories of Emotion, edited by Robert Plutchik and Henry Kellerman, Academic Press, 1980, pp. 3–33.

Another red flag is any list with exactly 10 items. That’s how many fingers we have, not how many things should probably be on that list. Instead, my lists of things like what goes into a great strategy or deciding whether an investment is worthwhile contain however many items make sense. Or in this analysis of why startups fail, the categories and quantity of bullets under each category are imbalanced. Or my system for PMF has steps of varying length and detail, and even gives counter-examples to show how it’s an interesting guide but not a law.

And so on with other models. If you’re modeling human organization, does it reflect the complexity and capriciousness of real humans, the good and bad incentives and emotions, the different personalities and ways those react to the world, or is it modeled as if people are fungible worker-units with predictable responses to stimuli, built by a professor who has never managed a team beyond six sycophantic grad students?

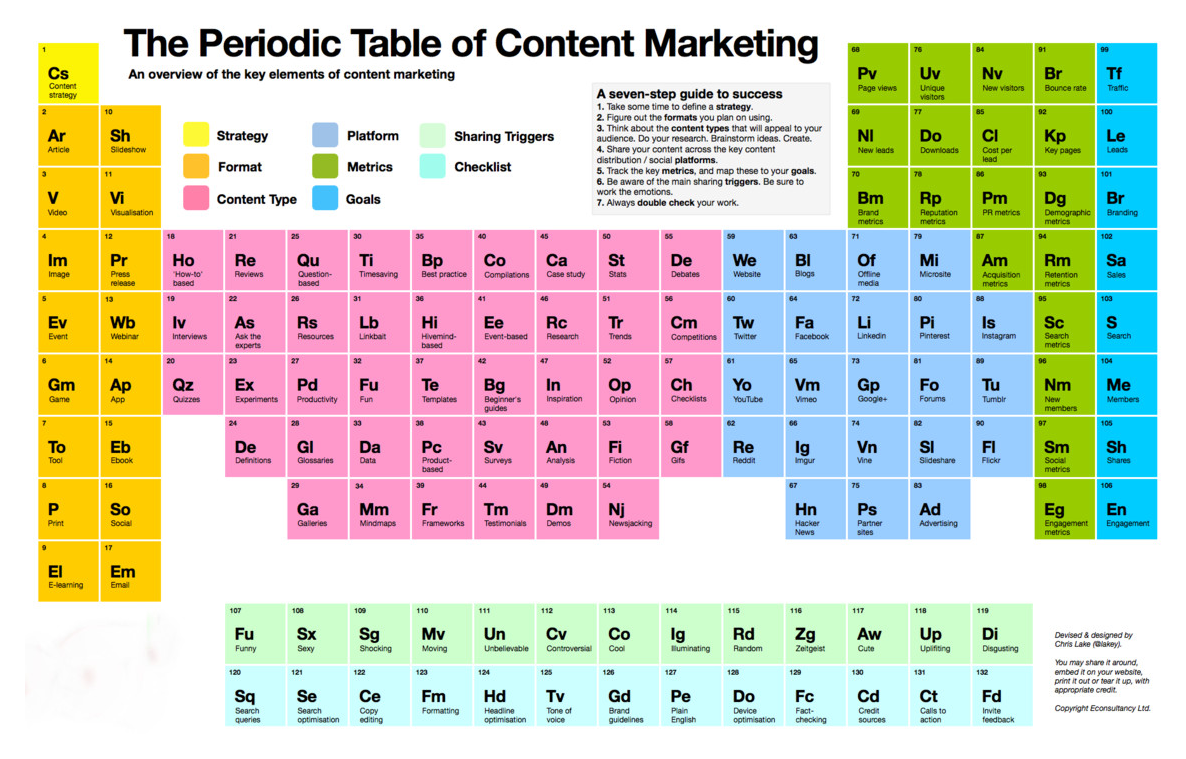

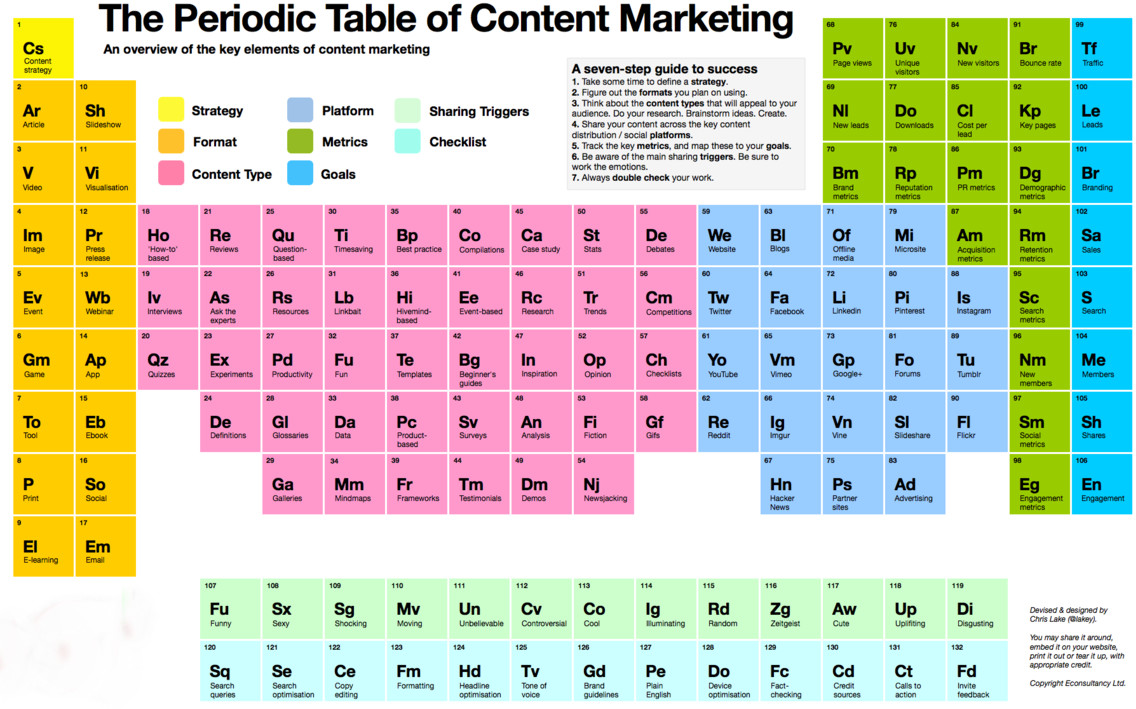

Figure 6: Obviously “marketing” does not have exactly these quantities of these things, that just so happens to perfectly fit the periodic table of elements.

Does the model of strategy fit into 2x2s and symmetric diagrams, with rubric scoring, with the same questions for all companies of all stages in all industries in all markets? Or does it grapple with the complexity of interacting systems of markets, customers, competitors, alternatives, employees, technology, products, and global trends, each of them dynamic, each affecting the others, each unknowable and unquantifiable in some of their most important dimensions?

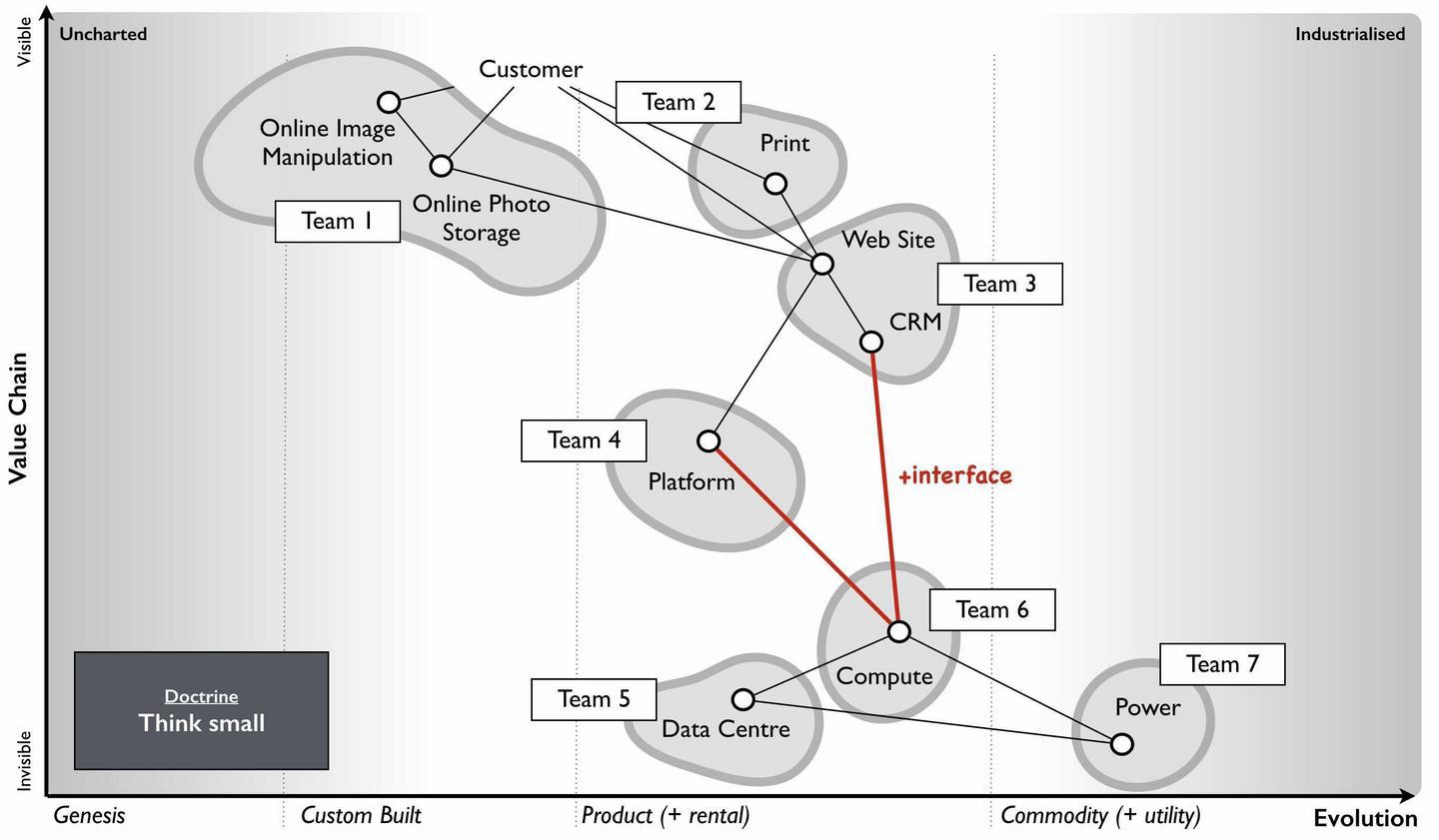

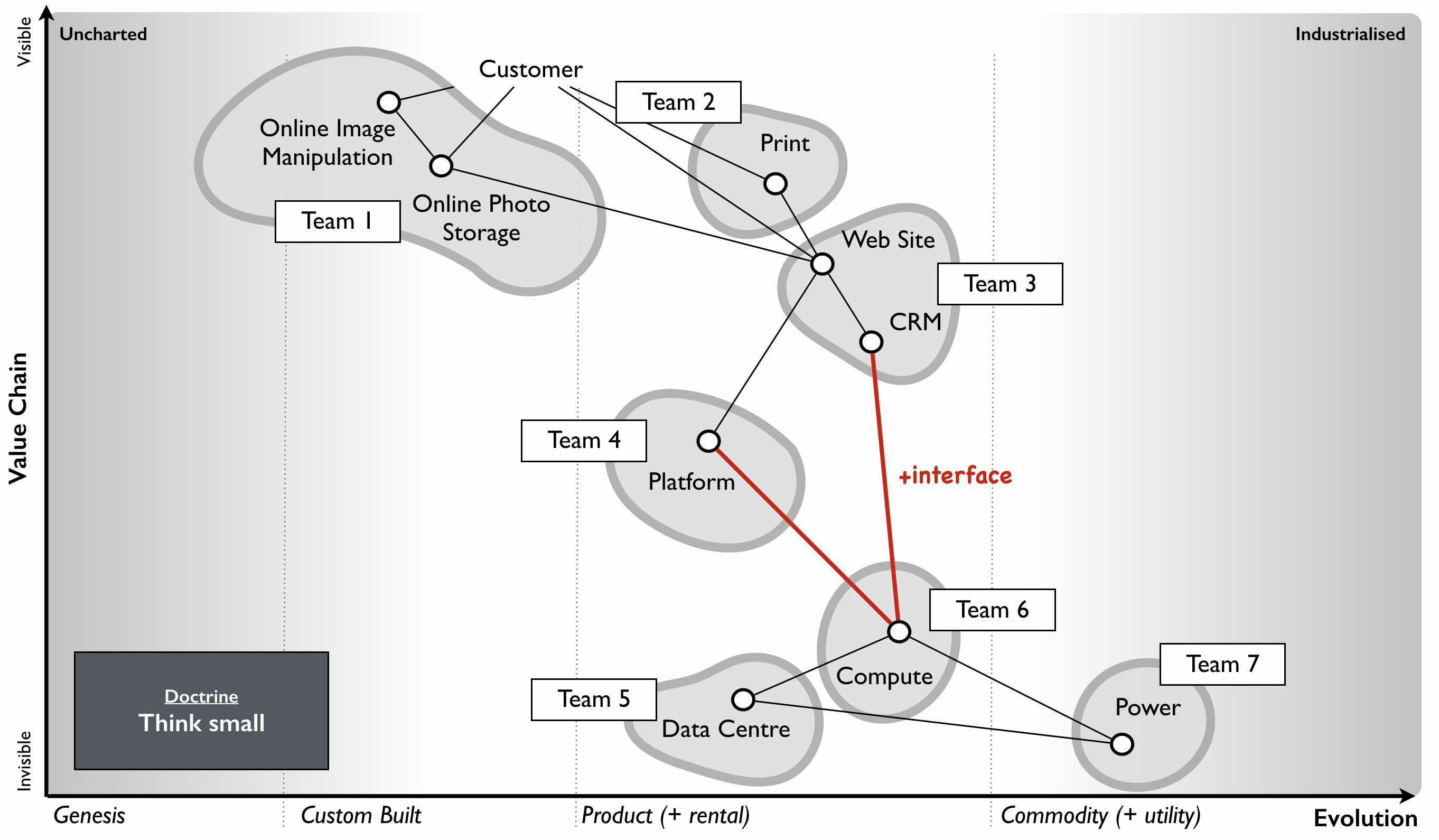

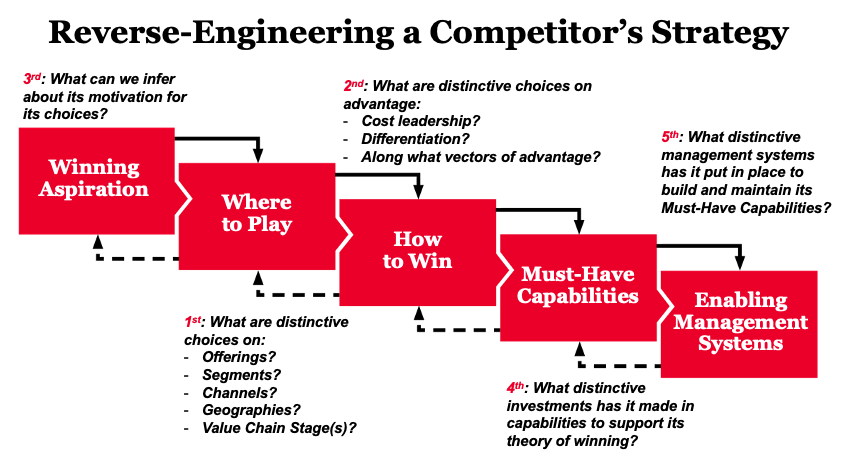

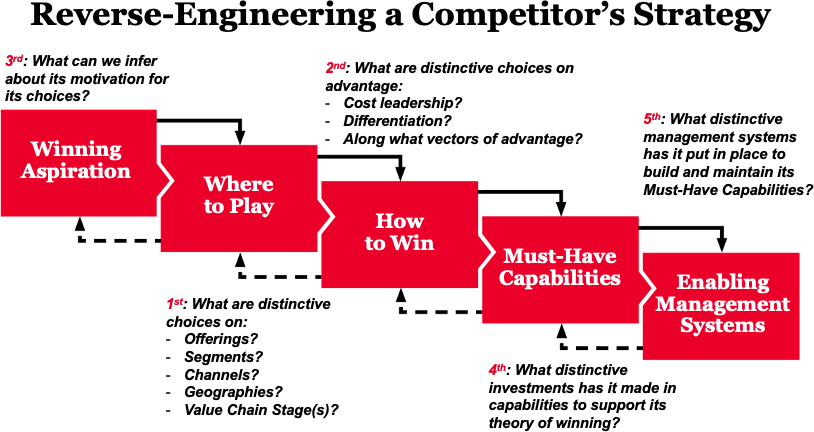

I trust more in diagrams that are imbalanced, asymmetrical, or even ugly, because perhaps they’re primarily interested in modeling the messy truth of the world, like in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7: Wardley diagram, sussing out which activities support growth and differentiation, versus which are necessary but commoditized, so that teams can respond with appropriate investment and action.

Figure 8: Though Roger L. Martin’s slide has “five boxes,” the instructions have “however many questions are useful,” and the order-of-operations is non-linear.

All models are wrong, but some are useful. The most useful are the ones that genuinely attempt to model the real, complex, ugly, asymmetric world, not the ones made to look pretty on brochures for consulting services.

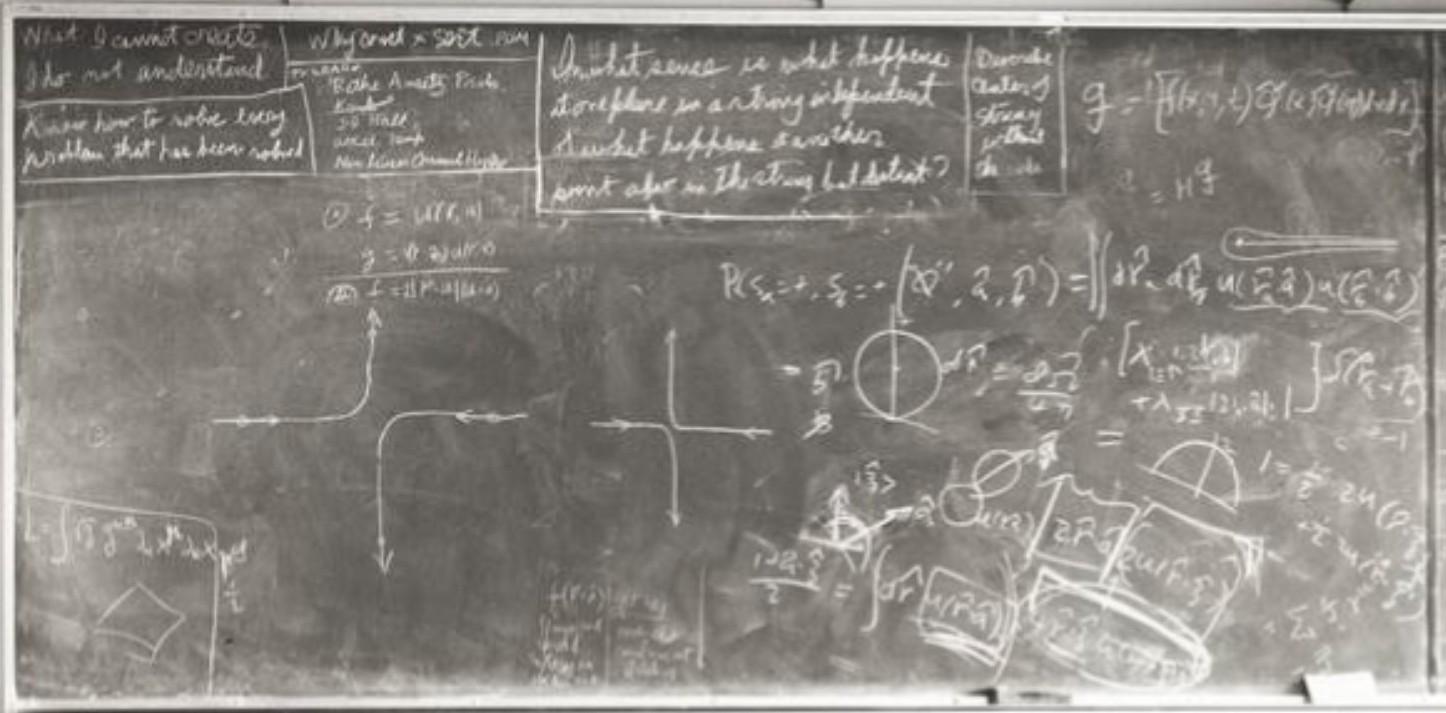

Figure 9: Feynmann’s blackboard when he died. The boxed statements at top-left are:

“What I cannot create, I do not understand” and

“Know how to solve every problem that has been solved”

https://longform.asmartbear.com/models/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF