The “Great” Product Manager, a.k.a. the Impossible Product Manager

What makes a Product Manager great? The prolific Shreyas Doshi1 gives us the list of requirements in a tweet-storm:

1 I highly recommend following @Shreyas, despite the following critique; he is a font of wisdom I have bookmarked and swiped many times.

- Great PMs consistently and singularly improve the company’s trajectory.

- Great PMs are masters of the art of blending quantitative and qualitative inputs, as warranted by each individual situation.

- Great PMs become the worldwide experts in their domain. When new to a domain, great PMs bootstrap this process by seeking the counsel of existing worldwide experts.

- Great PMs are diligent about using a variety of user research methods to inform what product to build in the first place.

- Great PMs also listen to what isn’t said [by customers] and anticipate where the industry overall is headed when developing their product hypothesis.

- Great PMs know that buy-in isn’t enough; you need passion & ownership to build great products. Great PMs facilitate discussions that get the entire team to come up with creative product ideas.

- Great PMs understand task leverage and spend the majority of their time on the highest-leverage tasks for the company.

- Great PMs, in the rare instances of product failure, improve not just their own approach but they also share the lessons learned with the broader company.

- Great PMs are adaptive—they have a wide repertoire [of tools and processes and workflows] that they expertly tweak for each specific team’s needs.

- Great PMs are outstanding problem preventers. Great PMs are discerning about which problems to prevent, which problems to solve, and which problems not to solve.

- Great PMs edit the company’s product ethos—they identify the unintended flaws in the principles, fix the flawed parts—and only then follow & espouse it.

- Great PMs know that career ladders are imperfect proxies: they’re more fixated on tangible competence & impact than on checking off boxes on the ladder.

- Great PMs also learn through work projects, but they learn a lot more about their craft in their personal time because of their curiosity & passion for self-improvement.

- Great PMs ultimately decide what’s best for users & the business.

- Great PMs ensure the product strategy is optimal.

- Great PMs work hard but are rarely overwhelmed.

Haha, that last one is funny. Don’t be overwhelmed, but also “learn a lot more about your craft in your personal time.”

These recitals always include a little “out,” an opportunity for the writer to wriggle out of responsibility for commanding the impossible. Something like, “The final rule is: You can break any rule, if you know what you’re doing.” In this case, the 31st tweet:

Naturally, very few PMs are Great.

And I don’t know any Great PM who does all of the above, all of the time.

That’s because Great PMs know that these ideas should be viewed as signposts, not as commandments.

So you could be super-human at two dozen different things. Now what?

I’ve used the following framework for Product Management at WP Engine to answer this question, so that as a whole team we in fact constitute the mythical omnibus “Great PM,” but we achieve it with a set of great—but plausible—real human beings.

The PM decides what to build

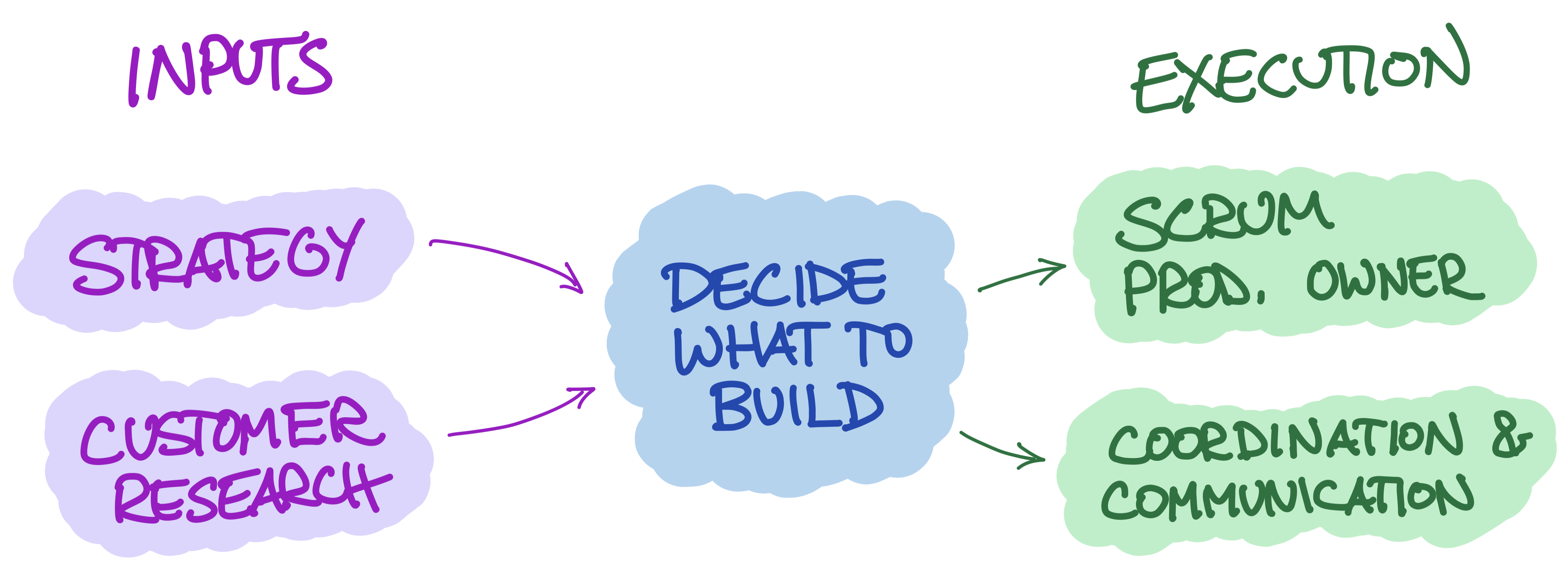

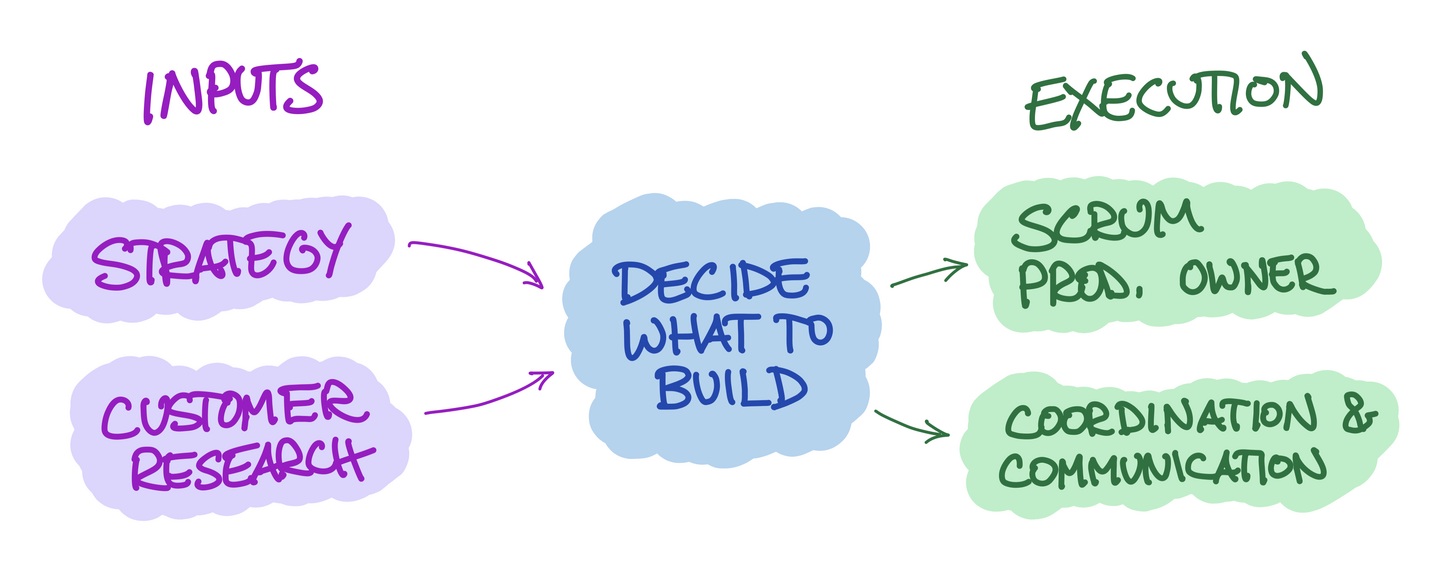

The role and scope of “Product Manager” varies between companies, but the role centers on deciding what to build:

Figure 1

Looking backward, there are inputs to the decision—the long-term vision and strategy, and an intimate and evolving understanding of the customer; these are part of Product Management, because without them we cannot make good decisions.

Looking forward there’s the execution of building and delivering to customers, the complexity of engineering execution together with coordinated efforts by marketing, sales, customer service, and external partners to deliver the entire experience to customers; these consequences of the decision are also part of Product Management.

You could argue that this particular break-down is arbitrary, however in my experience this categorization is especially actionable for hiring, careers, and designing the PM organization, and is compatible with other ways2 of decomposing the role.

2 Product thinkers categorize PM roles in myriad combinations. Lenny Rachistky in a podcast says it’s three things: (a) Shape the Product, (b) Ship the Product, (c) Synchronize the people. Later in the same podcast he says it’s five skill areas: (1) Execution, (2) Collaboration, (3) Leadership, (4) Vision + Strategy, (5) User Research. In another blog post he lists the ten jobs of Product Management. You’ll find the four areas below align with any of these break-downs; while all paths arrive at the same destination, I find this one particularly useful in working with real-world people.

The four roles of Product Management

- Strategist

- Analyzing, crafting, communicating, and updating the answer to the question: How do we apply our durable advantages to the opportunities in the market, to win? What do we look like in the success-case, years from now? What are the most important challenges to achieving that? Specifically what must we do in the coming years to overcome those challenges? Competitive analysis, market analysis, customer analysis. Determining the few, key personas to focus on. Distilling noisy data into clear identifications of internal strengths, external challenges, and market opportunities. Positioning the product to maximize value and perceived value, and thus price and willingness-to-pay. Selecting the right high-level metrics to drive the right long-term results, while also acknowledging that not all important things are numbers, and that revenue and retention are outputs of great strategy plus great execution, not themselves a strategy or even an operational goal. Having the fortitude to make decisions that will affect us for years, and cause us to say “no” to 90% of our ideas, so we say “yes” to exactly the right ideas.

- Customer Whisperer

- Not just listening to customers, hearing them, understanding their underlying needs, motivations, even their emotions. Not order-taking the features they know how to name, but rooting out the things they worry about so much they would pay to decrease the worry, or figuring out the result they need to get to earn a promotion or achieve their ultimate goal, as opposed to just “features.” More than figuring it out, wanting to figure it out. Having the “taste” to sense what features would be especially useful even in the absence of clear quantitative data, or the nuance that separates a serviceable UX from a delightful one that causes an NPS-10 customer to actually “Promote” in real life. Translating these insights into tangible feature ideas or use-cases of things to build that make the customer a hero.

- Scrum Product Owner

- An unfortunately ambiguous phrase for the uninitiated, the Scrum “Product Owner” owns the work-backlog, and works with engineering to execute it. Owning the work from start to finish, breaking down epics into stories, prioritizing and scheduling innovations for customers against engineering demands against requests from other teams against the broader needs of the company. Working tightly with engineering not just to shake them upside down until estimates fall out of their pockets, but working together to solve the puzzles of “most value (whatever that means) in the least time (or risk),” together finding the 80% solution that will take 20% of the time, so that we deliver quickly and learn quickly. Using the tools of story points and velocity and retros for team-wide constructive introspection and improvement, fulfilling the responsible aspect of being “self-managed.” Stretching to maximize how much we deliver, but practical and celebratory so that constant striving doesn’t turn into death-march burn-out. Being in command of the product and team.

- Orchestrator

- Delivering the “ Whole Product,” as Geoffrey Moore defines it, means not delivering working code only, but also enabling others: Marketing to grab attention and spark curiosity, sales to convert potential energy (leads) into kinetic energy (sales), customer service to shepherd the customer through good times and bad, enabling the Marcomm teams for PR and events, and external integrators and consultants who operate on behalf of clients. Tracking and communicating status, the good news and the challenges, celebrating the wins and facing the challenges with crisp articulation, calming stakeholders in the knowledge that the team is fully aware of what they need to overcome, and thus in command even in dire situations. Running great meetings—starting with a clear goal and how the discussion will support the strategy, tight agendas so participants come prepared and use synchronous time wisely, with decisions made and recorded. Engaging the whole company on occasion, with inspiring presentations at all-hands meetings so everyone is excited about we’re accomplishing together, and so that the teams working directly on the product feel proud, and feel seen.

The conclusion is not that “a Great PM must be the master of all this.”

In fact, exactly the opposite.

One excellent, one good

In my experience, echoed by a few people I’ve chatted with, there is a general rule of thumb vis-a-vis the categories of work above:

A “Great PM” is

excellent in one area,

good in at least one other,

and doesn’t have time for more than two.

Using “Great PM” language, you should strive to be “Great,” as superlative as possible, in one of those four areas, and pretty darn good at a second.

I find this particular categorization of four job-areas aligns well to strengths and abilities of real people. Whatever you ascribe to nature or nurture, instinct or experience, for each of those job-areas I can immediately recall specific people who are excellent at nearly all components within a single area, but variously good or lacking in components of a second, and then completely the wrong temperament or lack of desire to excel in others. These four “buckets” seem to me to be natural divisions of ability and proclivity.

I don’t believe in magical unicorns who are excellent in all four areas.3 But suppose they do exist, and you hired them. Would it be physically possible to execute well in all four areas? It’s easy to see that it’s impossible, if you add up the time it takes to do great work.

3 Perhaps there are, but the probability that you’ll find one, or hire one, or build a whole organization of them, is near-nil, although you will surely find a lot of candidates who imagine themselves to be one.

Strategy is on-going—markets change, competitors change, customers change, new data comes to light (usually only after expending considerable time acquiring it), and whenever you’re “pencils down” on one iteration of a strategy, there are always eight more things you still haven’t figured out yet. Customer discovery takes a long time—scheduling and running interviews, compiling results, mapping what you heard, prioritizing activities or opportunities or use-cases (depending on your frameworks), trying to (in)validate assumptions with data. Being a Product Owner takes at least twenty hours per week to write great stories and run Scrum ceremonies. Anyone who has program-managed multiple teams across multiple departments knows that scheduling and organizing and cajoling and status-updating and data-gathering and meeting-preparation takes a lot of time. Even with sensational skills, no one has time to do it all (with excellence).

We are not going to breed a new race of super-humans; we will have to run our organizations with the humans we have.

—Peter Drucker

While one person cannot be all things to all people, across the entire product team, you do need excellence in all four areas. Thus the manager of a Product organization isn’t simply a “manager,” but rather an “organization designer,” choreographing this outcome through intentional hiring.

You’ll often find these roles in titles other than “Product Manager.” Communications and collaboration is often done by a Program Manager—a role where if you think it’s not useful, it might be because you haven’t worked with someone who is great. Marketing, sales, and support enablement is often done by Product Marketing (i.e. somewhere under the CMO rather than somewhere under the CTO). With highly technical back-end teams with little or no customer exposure, a sociable engineer or architect can be the perfect Product Owner. Mature organizations might have UX Research teams who are expert in customer analysis—building data-based personas, crafting interviews, compiling results, and pooling insights across multiple product teams who happen to share customers.

As the organization designer, your job is to “assemble excellence” in all areas. Even incremental improvements here can be impactful, because so often organizations have excellence nowhere. 95% of employees complain they don’t understand the strategy, or don’t know their role in it; founders-in-PM-roles often run on instinct more than systematic customer analysis; engineering teams often complain of underspecified or under-explained stories; engineers are often surprised at the gulf between what they know to be true about the product and what Sales claims on the phone, just as customer service folks are often surprised at the gulf between what they know to be true about the product, and what engineering thinks is “a job well done.”

Rather than unicorn-hunting, take this more practical route in your career, or in designing your team.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/great-product-manager/

© 2007-2025 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear Simple eReader (Kindle)

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF