Adjacency Matrix: How to expand after PMF

Expansion

Our everyday craft of incremental product evolution is obvious and natural.

We hear from customers in emotionally overcharged outbursts on Twitter, or public reviews encoding their ire or gratitude, or filtered through the problem-solving of tech support, or teasing us with an if-you-build-it-we-will-come sale that hasn’t yet (and may never) close. We then convert what we thought we heard into features and bug-fixes, prioritized by impact and growth ideally, but more likely by pride and intuition; sometimes we get lucky and these are the same thing.

This works, after Product/Market Fit. That is, once everything is fundamentally working, and the job is “don’t break what’s working.” Then we should incrementally add utility and delight while not disrupting the money-making flywheel. Before PMF, it’s not working yet, so the job is to identify what can work, and for whom, not to make slight adjustments to something that’s not working.

But then we come to another post-PMF decision: When and how to expand the scope of the business.

Not a pivot—that’s for companies that are staring death in the face, that must strike out in a new direction for a chance at survival. Rather, an expansion—to keep what’s working, but sprout new shoots in new directions. Adhering to the rules of great strategy by leveraging existing assets to attack a valuable new opportunity with asymmetric upside. (Add your favorite buzzwords; those were mine.)

When is the right moment to venture into new territory, rather than building obvious, incremental things with little risk?

- Bottlenecked growth

- If existing marketing and sales channels are at their limit—when spending more time or money doesn’t yield more output, or at least, not cost-efficiently. In that case, an expansion to a new channel, or new geography, or new market segment, accelerates growth.

- Target market saturation

- If you’ve already won 5% or more of your perfect market. Some people use acronyms1 to name this concept; I mean of the total number of people who are your ICP (Ideal Customer Profile)—oh goodie, another acronym—the absolutely-perfect-in-every-way customer whom you are targeting with all your marketing and product features. 5% is not saturation, but if you got to 5%, you can presumably get to 10% with similar methods. Since you’re well on your way to that already, you can afford to turn your attention to segments that are similar enough to be relevant, but different enough that they require effort to serve well.

- Diversification

- Adding new marketing channels, new target markets, new geographies, new pricing options should not only add growth, but make the company more robust to market and economic disruptions. At WP Engine we experienced this after expanding upmarket. It wasn’t just “growth”—addressing a new segment meant our value proposition became different. Small businesses saw us as “expensive, but the best,” whereas large companies saw us as “low cost, yet still enterprise-grade.” This diversification of positioning resulted in robust growth during the COVID crisis, where smaller companies were going out of business (i.e. “expensive” is now bad), but larger companies were looking for ways to save money (i.e. “low cost” is now good). When one segment has difficulty, the other grows; the net effect is stability. At scale, this is nirvana.

- When you can afford to invest

- A company throwing off more than a million dollars a year in profit can afford to try something new; failure in a new investment is not fatal. Expansions are both costly and risky; extra money covers both liabilities. Extra money could come in the form of outside investment or profit draw-downs, but either way it’s a bet, it’s an investment, and the typical investment rules apply.

1 TAM (Total Addressable Market), or SAM (Serviceable Addressable Market); there’s more.

If one of these conditions is met, we come to the crux of this article: How do you decide in which direction to expand?

Adjacency

The key idea is “adjacency,” meaning “close by.” The difference between incremental change and expansion is that expansion is “somewhere else,” but the difference between expansion and something too far afield is “adjacency.”

You don’t want to go so far afield that you’re not leveraging existing assets, and thus it is too risky, and too costly, such that even if the opportunity is large and tangible, it’s still a bad idea for you. A great strategy—that doesn’t align with your strengths—is a bad strategy for you.

It’s not hard to think of ways to expand the business. You could enter a new geography. You could target a different ICP, different niche, different vertical, different use-cases. You could go up- or down-market in the size of business you sell to or in the customer’s Needs Stack. You could add a freemium tier, add a higher pricing tier, add a lifetime plan, add a new product line. You could expand from iOS-only to add Android, from web-only to mobile-app, from integrating with one third-party to ten. You could venture away from the reputational investment of SEO and social channels into the analytical world of paid marketing, or venture from the pay-for-today world of advertising to the invest-in-the-future world of SEO and social.

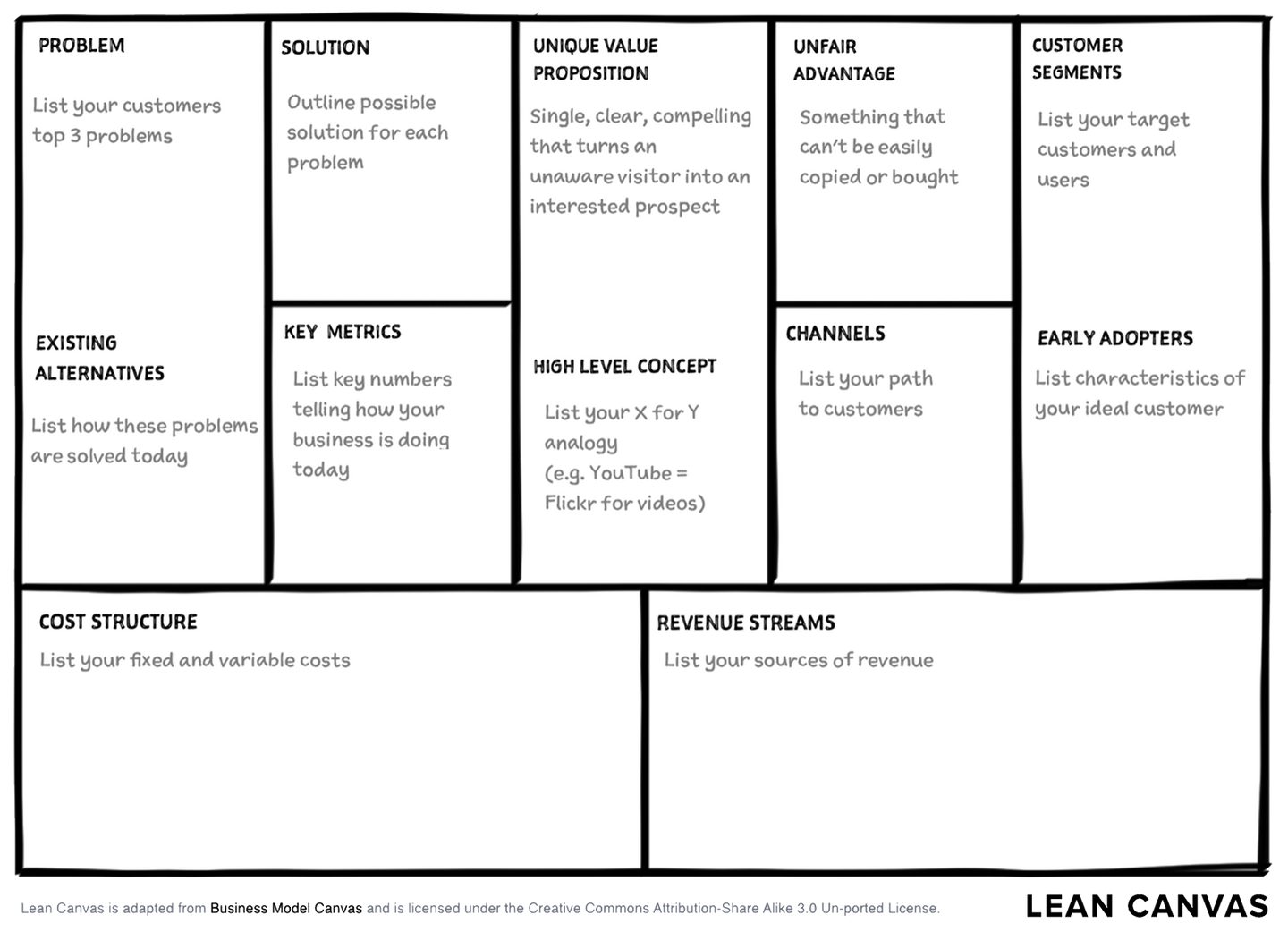

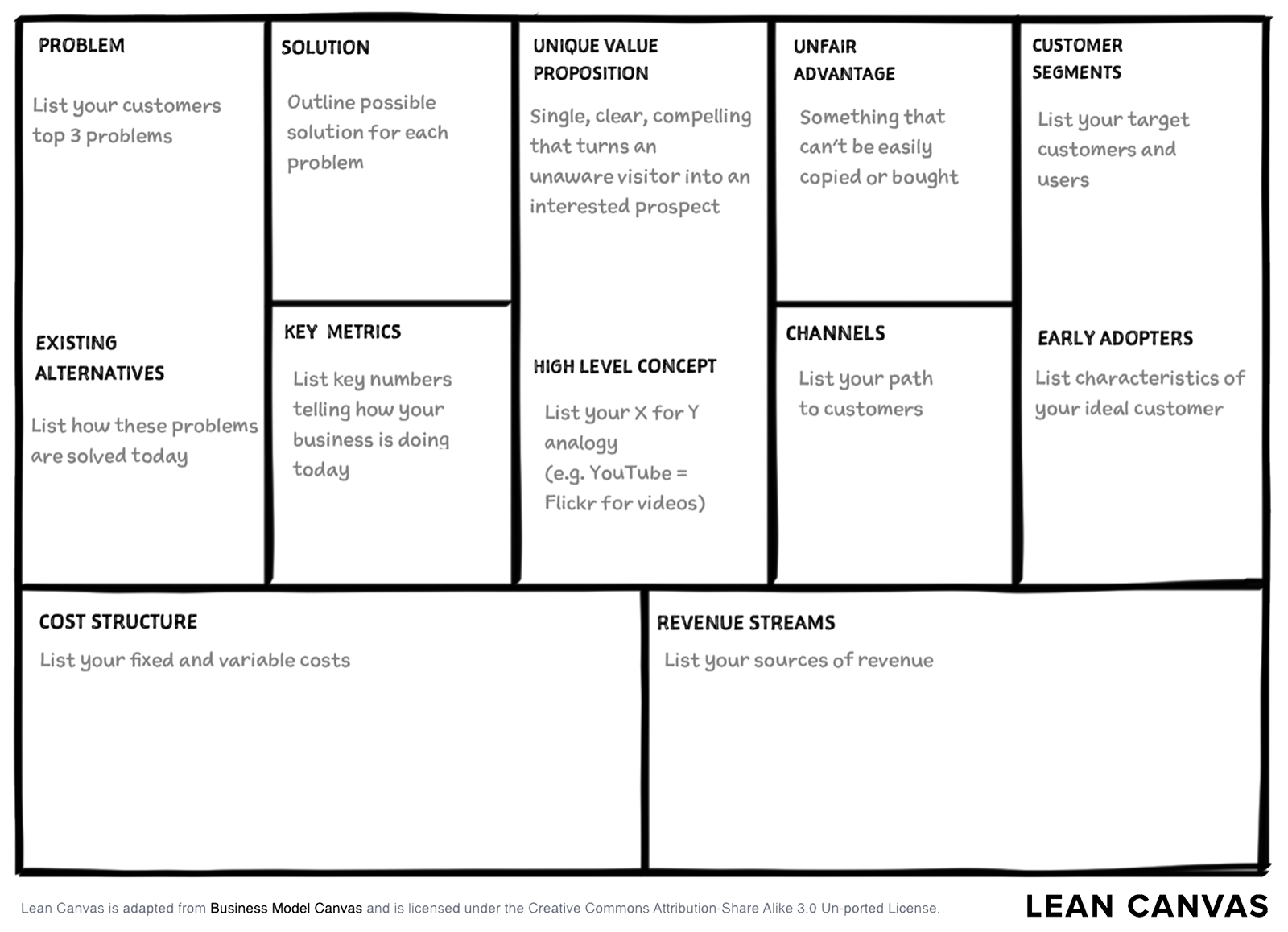

If you want to be more systematic, you can use something like the Lean Canvas to ideate:

Figure 1: Ash Maurya’s version of the popular business model “canvas.”

Fill each box according to the existing business, then brainstorm2 ways that you could expand or improve on each box.

2 Here are some fresh and fun ways to brainstorm these sorts of ideas. LLMs can be helpful—not to select ideas, but to generate possibilities.

Calculating the potential upside of these ideas will of course be specific to the idea and the company. In this article, I give my general framework for evaluating the cost and risks of executing those ideas, answering the question: How adjacent is this idea to the current business?

The Adjacency Matrix

Start with a table of the major functional areas of your business. It will be similar to the following, but tune it for yourself. For example, a company leveraging product-led growth may have no Sales department, but might have a heavy design culture and thus would add a row for Design.

| Functional Area | Types of Activities & Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Marketing | getting attention; brand personality & positioning; acquisition channels |

| Sales | processing leads; managing the sales process; pitch & competitive materials; domain expertise; sales training |

| Service | expertise; technical knowledge; domain expertise; product training |

| Product | understanding the customer; mix of data and intuition; roadmaps; everything else |

| Engineering | platforms; architecture; major libraries & frameworks; tech debt; infrastructure; specialized skills and knowledge |

| Business Model | Pricing and packaging; unit economics; profitability; budgeting |

Now evaluate the “adjacency” of your proposal by determining how much each of these activities must change to support the new initiative. Your only choices are:

- ✅ Trivial—Almost no changes required. “Training” is an email or one Zoom session. Adjusting sales and marketing material means adding a few bullets.

- ⚠️ Adjustment—Change-management required, but manageable within current processes, norms, and organizational structure, similar to a “large new feature release.” Requires training. New sales slides. A new web page for the website. A non-trivial change to pricing and packaging. New SMEs in Support.

- ❌ Overhaul—Major change needed: hiring for new skills or for capacity, significant retraining that might require new specializations, structural process or management changes, especially if the org chart is changing. Often you’re not entirely sure of the full extent of the changes, i.e. it is sufficiently complex that we can’t identify all the challenges and risks that await us.

Longtime readers will recognize this as another instance of my Fermi Estimation3 hobbyhorse, in which we intentionally limit choices to avoid arguing over details and predictions that we aren’t qualified to make anyway. Sorting into one of these three buckets should be relatively easy, without extensive analysis.

3 Described completely in how to use Fermi estimation for ROI-type decisions, including both objective dimensions like “time” and subjective dimensions like “what makes for a compelling product,” and echoed in pieces on probabilities, evaluating markets, and making big decisions, among others.

As an example, I’ll take our company WP Engine in 2013 when our ICP was “small to mid-size company’s home page and small to mid-size blogs/media, often built by freelancers and small agencies.” We’ll evaluate two ideas: (a) expand to support marketing campaigns run by Enterprise-sized companies, and (b) expand to host the main websites of Enterprise-sized companies:

| Functional Area | Enterprise Campaigns |

Enterprise Full Site |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing | ⚠️ Adjustment (new target audience, and message of “campaign” instead of “home page”) |

❌ Overhaul (completely new competitors, new marketing channels, establish brand from scratch) |

| Sales | ❌ Overhaul (drastically new sales processes and cycle times) |

❌ Overhaul |

| Service | ✅ Trivial | ❌ Overhaul (e.g. new people and specializations like account management and white-glove onboarding) |

| Product | ✅ Trivial (campaigns don’t require new features) |

⚠️ Adjustment (new compliance requirements, but few new features) |

| Engineering | ✅ Trivial | ✅ Trivial (enterprise websites get similar amounts and types of traffic as popular websites belonging to small companies) |

| Business Model | ✅ Trivial (existing plans are sufficient) |

⚠️ Adjustment (new plans, but same business model) |

In this case, the conclusion might seem obvious—of course it’s easier to serve a small use-case in a new segment (“Enterprise”) than it is to compete in a major use-case in a new segment.

What might not have been obvious is how dramatically different it is to “sell to the Enterprise.” Often startups claim this as their growth path, even when they’re at only $500k in ARR. This is definitely the wrong strategy at that moment; this exercise makes it clear, yet companies often conclude the opposite. They should instead be considering simple use-cases at larger companies, or they should be ignoring the complexity of large companies so they can continue winning where they are already strong.

Furthermore, it shows how much investment is needed if you insist on investing in Enterprise. Sometimes that is the right strategy. After all, calculating “how adjacent” is about evaluating the decision, not dictating it. If, for example, a company is at $60M ARR with steady growth in absolute dollars but slowing as a percentage of revenue, spending $10M to add an Enterprise-focused business model could be a great growth strategy.

In particular, when more than one area requires a “full overhaul,” that’s a deal-breaker if this is supposed to be an incremental, sustaining innovation. If multiple areas require a full overhaul, this is only acceptable if (a) you are willing to make a huge investment and (b) you’re willing to take a large risk that it will not pay off, and this only makes sense if (c) the potential upside is enormous. This reiterates the first rule of investments.

At some point, the idea is so non-adjacent that it’s definitionally a bad strategy to attempt it, regardless of upside. Strategy is supposed to leverage existing assets; don’t select something that doesn’t do that.

Selecting the best option

It is tempting to use a value-divided-by-cost analysis to decide which idea to select, where “value” is some estimate of upside, and “cost” is some formulaic summary of the Adjacency Matrix, or possibly an actual dollar or time estimate.

If you are so tempted, I recommend this ROI system, which will force you to be rough in both variables, ideally bringing the best ideas to the top of the list with a minimum of debate.

However, whenever you are making an investment—doing something with substantial cost, time, risk, and only hopeful upside—I recommend solving first for maximal impact, and only secondarily for cost. The reasons are given in that article specifically in the context of investments, and also in my work-prioritization system that extends the Rocks, Pebbles, Sand analogy. You might want to use Binstack to identify the items of highest value, only then looking to cost and risk to break ties.

In this context, the Adjacency Matrix is useful for ruling out ideas that are clearly too far afield, or identifying those which are particularly low-risk.

The Adjacency Matrix outlines your cost and risk analysis, identifying the areas of the business that must be considered. For changes that you already understand, you can describe what needs to be done, what the budget is, and what risks remain. For complex changes, especially the dreaded “unknown unknowns” likely to arise from Overhauls, you’ll need to include more: the mitigations you will put in place, objective measures or milestones to catch problems as early as possible, how you will attack the high-risk, high-uncertainty areas first, and specialized hires who have seen this movie before.

Finally, the Adjacency Matrix is useful in communicating the decision to the whole company—something leaders perennially fail to adequately appreciate and value. It’s vital that the decision is simple to explain and justify, so everyone feels that it’s natural, intelligent, and clear. The matrix can help form the narrative:

We’ve all seen the organic pull from larger, enterprise-sized customers. There’s obviously opportunity there, but what is the right way for us to approach it, starting from where we are today?

We considered several options, such as ______ and ______. We decided upon ______ because while it will require [department] to [do something complex and risky], we realized it would be easy for everyone else because [why it’s trivial in other areas]. So, this was the least-risky, highest-chance-for-success way for us to approach this new market, add a new growth area, and learn, and see where it goes from there.

Exciting! And let’s remember to give [department] our support and grace as they transform themselves to support this new strategic effort.

Congratulations on hitting Product/Market Fit, starting to scale, and now having the “good problem to have” of where to expand next.

Hopefully this will help you make the right decision.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/adjacency/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF