Quarterly strategic planning using the fairytale structure

Using the narrative structure of the fairytale, we can execute the classic “Double-Diamond” design pattern, driving our analysis, decision-making, actions, and our final exposition, in an intelligent, systematic way that everyone can easily understand.

It’s going to look like this:

- Objectives: What are we trying to get / what happens if we don’t?

- Obstacles: What stands in our way?

- Actions: How do we overcome the obstacles while advancing our objectives?

- Measures: How will we know we’ve been successful?

- Not Doing: What important things have we chosen not to do, so that we can achieve the above?

Now let’s tap into humanity’s collective unconscious, and see exactly how to run this framework in practice.

The Fairytale cheat code

The fairytale structure is thousands of years old, crossing all peoples of the globe, a reflection of a deep, shared humanity.

You’ve heard it your entire life, from centuries-old childhood stories to every Pixar film to advertising to the news, so you need only a reminder, not an explanation:

- Once upon a time there was an unsuspecting hero.

- Every day, the way things are.

- But then, one day, change/event that motivates action.

- And so adventure begins.

- It was almost impossible because challenges/obstacles.

- Until finally victory.

- And forever after, the world is different.

Fairytale structure is a cheat code for effective communication, as journalists have exploited for years. For example, this simple “case study” that I’ve used in sales calls at WP Engine takes less than a minute to tell:

One of our customers is ______. Like you, they are a popular food blogger, making money through advertising and occasional affiliate product sales. One Thanksgiving, on their busiest day of the year, their site crashed because of all the traffic; they missed out on thousands of dollars of revenue and hundreds of newsletter sign-ups. They moved their site to us, and that never happened again; they just focus on their work, build their brand and business, and never worry about technology.

It’s equally effective for presentations, fundraising, and product proposals—a ready-made outline, resulting in a straightforward narrative structure. Our brains are pre-wired for fairy-tales, so we naturally follow the presentation as it flows into those primordial ruts in our gray matter.

A less obvious but extremely powerful application of this principle is in creating a strategic plan, i.e. analyzing the current situation and deciding what needs to be done. For a single team, this means being in command of the most critical things that need to be done right now. For a department at a larger company like WP Engine, this is how I build our quarterly strategic plans.1

1 It looks like I’m just slapping the word “strategic” on everything, to make it sound important. Indeed, people often do that. As you’ll see, the purpose of this is to connect work to the strategy, so it really is strategic planning!

Over the past two years, together with a few product teams at WP Engine, we’ve created and honed a simple but effective framework for the Fairytale Plan—strategic work-planning that has worked well both to drive the process of figuring out what the plan should even be, as well as communicating the result throughout the company. The process is akin to the widely-admired Double-Diamond design process, and the final result matches the fairytale structure.

No wonder it works, and resonates with everyone.

Here’s how you can do this too.

The narrative structure of the strategic Fairytale Plan

Here’s how our strategic plan will look, and the guiding questions that help us create each section.

| Strategic Plan Narrative | Guiding Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives | We must advance our strategy by achieving these objectives. Fairytale 1. Once upon a time… 2. Every day… |

• What is happening now? • What do we want? • What happens if we don’t get it? • If we weren’t encumbered by roadblocks, with no distractions and no interruptions, how would we advance our strategy right now? |

| Obstacles | But obstacles stand in our way. Fairytale 3. But then, one day… 5. Obstacles2 |

• What is standing in the way3 of “what we want?” • What makes it difficult to achieve the objectives? |

| Actions | So here’s what we’re doing. Fairytale 4. Adventure begins… 5. Tackling obstacles… |

• How do we overcome the obstacles… • …while advancing the objectives? • …with the people and capabilities and strengths we currently have? • What changes need to be made, so that the answer becomes obvious? |

| Measures | Here’s how we’ll know whether we’re making progress, and when we’re finished. Fairytale 6. Until victory… 7. The world anew. |

• How will our company be different? • How will we know, objectively? |

| Not Doing | Important topics and ideas that we’re not doing (yet). | • What do we really want to do, but have to wait so that even more important or urgent things can be done? • What did we leave out that is controversial? |

2 In a fairytale it’s fun to surprise the hero with obstacles. Our plan must do the opposite: Clarify the obstacles up front.

3 There are many kinds of obstacles: internal execution challenges, interruptions, dependencies, competitive pressure, market dynamics, just to name a few.

There are techniques and pitfalls for each of these sections. Here’s how to navigate it:

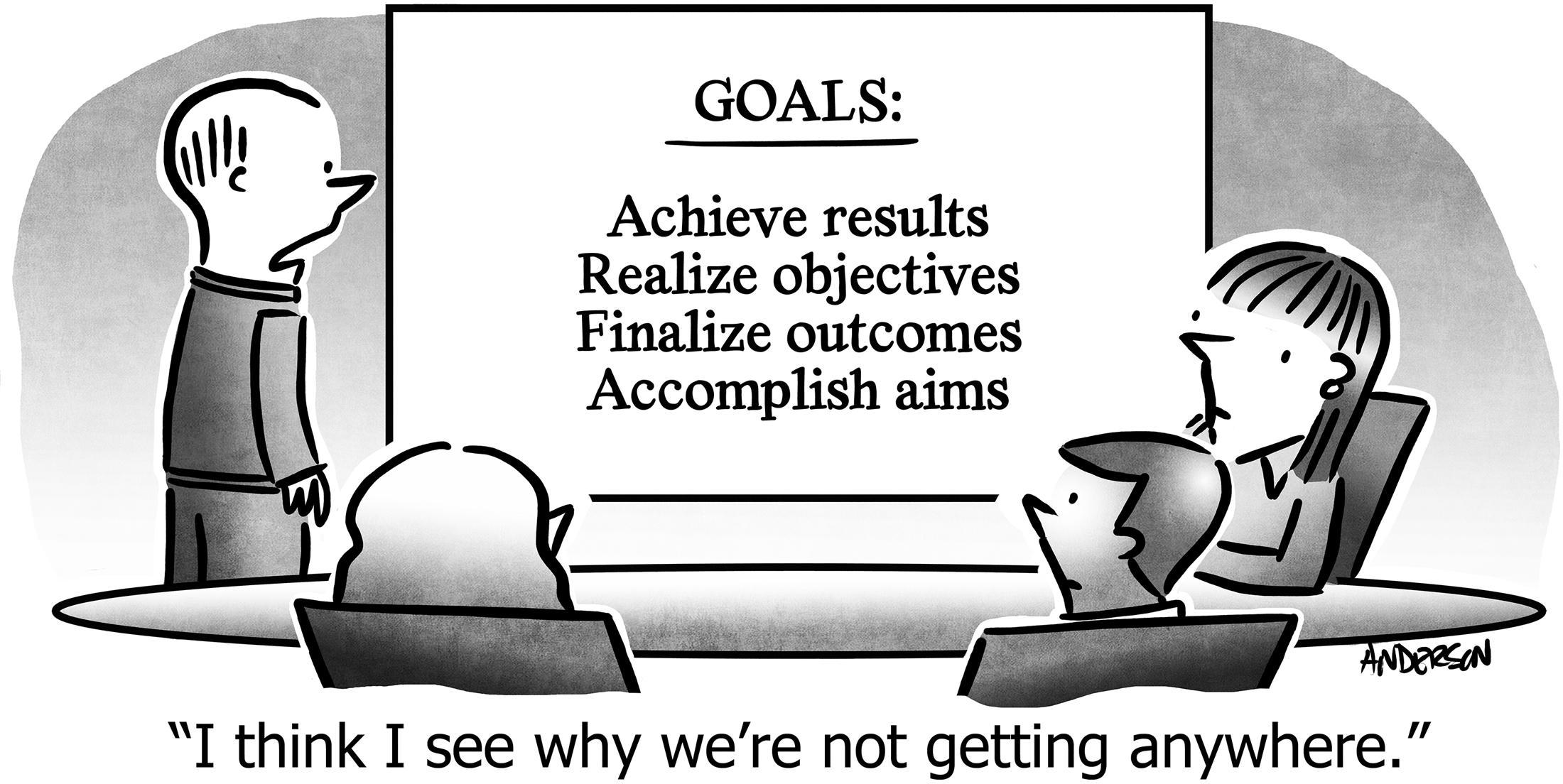

Strategic Objectives

Narrative Plot Point

We must advance our strategy by achieving these objectives.

Guiding question

If we weren’t encumbered by roadblocks, with no distractions and no interruptions, how would we advance our strategy right now?

Why can’t we skip this section?

If you run very fast in the wrong direction, you fail. This names the right direction.

Objectives shouldn’t summarize the entire strategy; your strategy document already does that. Instead, link to that document for reference, and highlight 1-3 specific objectives as the subset of the strategy that make sense to advance right now.

“Right now” is the difference between this plan and your strategy. The strategy is the long-term vision and the main ways that you will achieve it. The plan is where you select the specific next steps that materially advance the strategy while achieving results that you need today. “Results today” is typically revenue growth, cost reduction, or some internal transformation.

Later in the process of creating the plan, when you’re determining how to achieve these objectives while also dealing with the obstacles, you might get stuck, unable to invent anything that works. In that case, you might need to choose different objectives. Or you might decide that “eliminating obstacles” is all you can accomplish right now—unfortunate, but useful to declare if true. During the planning process you should expect and even encourage fluidity between exploring the problem-space and solution-space.

The specific objectives will evolve over time, but it’s OK if they’re the same for a few quarters in a row. Indeed, that gives the team stability and focus. How do you know if you’re sticking with an objective for too long? Later you’ll be asking the question “how will the world be different.” If there are good answers, then we’ll know whether we’re making progress, despite the objectives remaining the same.

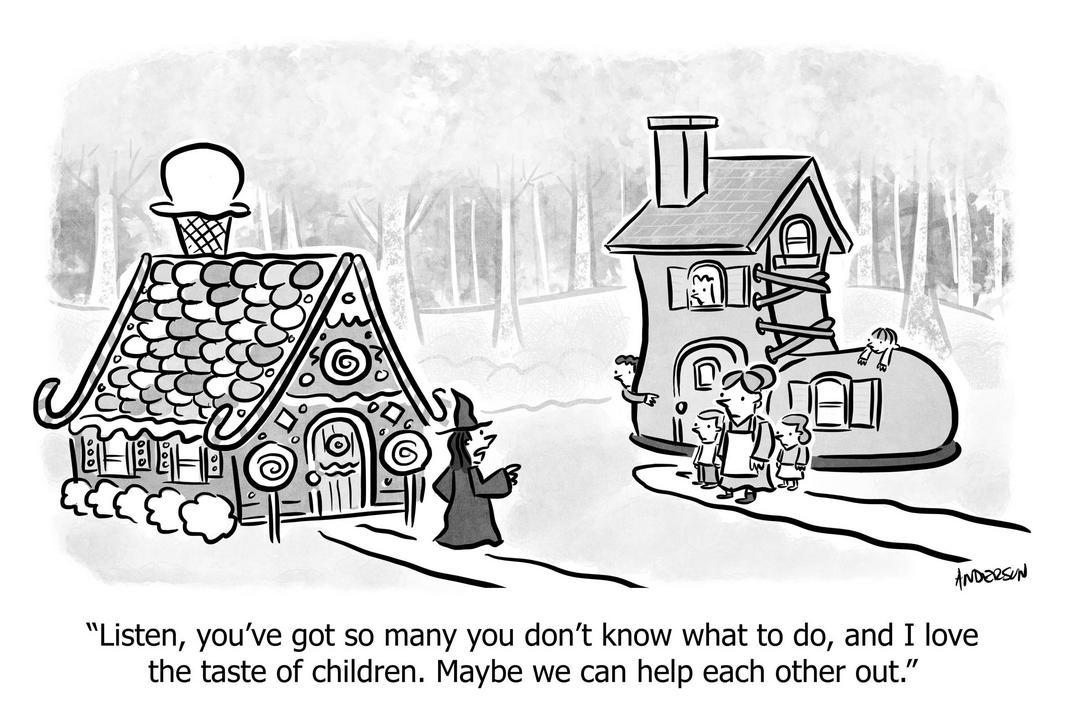

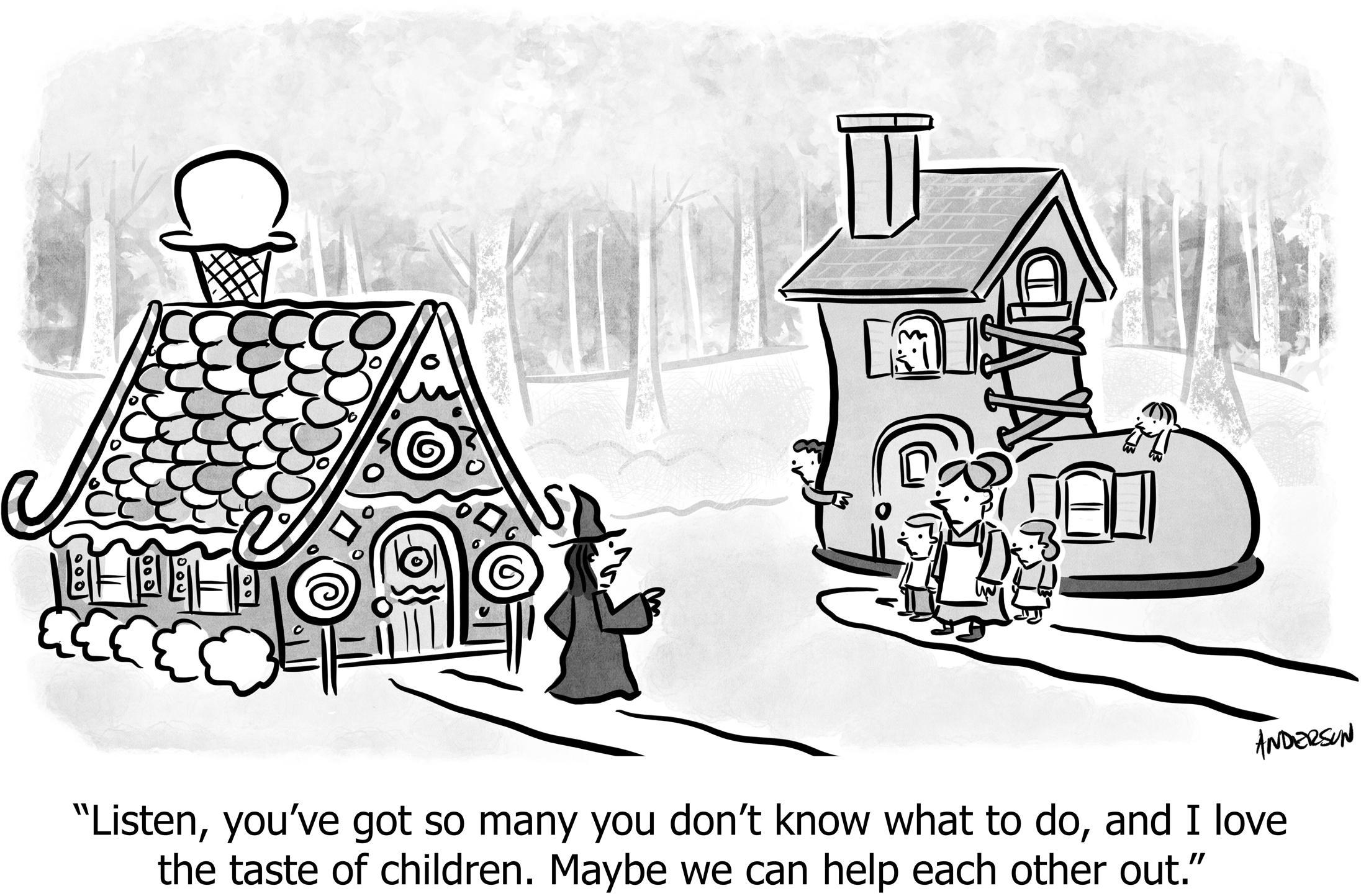

Obstacles

Narrative Plot Point

But obstacles stand in our way.

Guiding question

What is preventing us from making rapid progress on the objectives?

Why can’t we skip this section?

Often the most important business challenges appear here, not in the objectives. This is where you face difficult truths about your current situation, which will ensure the work you select will actually overcome them.

If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.

—Albert Einstein.

I agree with Einstein (but then, who among us is in a position to argue against Einstein?). This is the most important section, and often where you’ll spend the most time.

You’ll be tempted to ignore Einstein, but it is crucial that you do not. You’ll want to jump right to the solution. You’ll say you’ve already talked about this stuff, and you know what to do. You’ll say you don’t want to rehash all our challenges; let’s cut to the action.

I understand, I feel the same way. I want to activate on any reasonably-good idea right away. But without fully exploring the problem-space, you’re not in a position to even know the goal of the solution-space. You’ll just keep repeating mistakes, keep avoiding the difficult truths, and you won’t improve.

It’s important to generate many options first; only by exploring the whole space will you uncover the things which are the most important to solve now. Your team will thank you for the clarity, not only about what they need to tackle, but what they’re allowed to leave alone, even though it’s on fire.

Here are some types of obstacles you should explore, in no particular order:

- Difficulty executing the strategy: “Why is this hard?”

- Executing the strategy might be intrinsically difficult, like building something we’ve never built before (thus maximally risky and uncertain), or having to create novel algorithms, or having to deploy infrastructure at scale, or pivots, rewriting, rebranding, or repositioning that will take intense effort and coordination. Whatever makes our strategic goals difficult or risky, is an obstacle that is definitionally strategic to remove.

- Team challenges: Humans are hard.

- Do we have the right skillsets on the team? The right experience levels? The right motivation? Are they burned-out? Is there enough people to do all the work?

- Competitive pressure

- Is a competitor winning business in a way that demands a response, even if it’s not directly related to our long-term strategy?

- Customer retention

- Are customers leaving at high rates,4 and therefore we have to address that immediately even if it’s unrelated to our long-term strategy?

- Interruptions

- Are we dealing with interrupt-driven work instead of planned work, such that we’re unable to make enough progress on strategic work? Do we need to do work to reduce the frequency or magnitude of the interruptions, perhaps through automation or rejecting certain types of work?

- Too many bugs

- Are we failing on our basic promises to our customers of quality and performance, due to mounting bugs or other issues? Do we need to attack those now, even if they are unrelated to our long-term vision?

- Dependencies / coordination

- Is it impossible for us to execute or deploy or iterate, due to some other team or process or platform or architecture? Do we need special coordination of work in order to achieve our own goals?

- Process bottlenecks

- Are our tools getting in our own way? Is our process preventing throughput? Not just nice-to-have improvements, but step-changes in our productivity, and likely also our happiness?

- Market evolution

- Are there trends that are making our current product or positioning less effective or less relevant? Does this even mean our strategy needs to change, to keep up with the changing external landscape?

4 My rule of thumb for “what is a ‘good’ cancellation rate” is: 3%/mo for consumer, 2%/mo for small business, 1%/mo for enterprise. More on that here.

Narrow these down to 1-3 most critical issues. The guiding question is: Which are the few issues where, if we solved them or took a huge bite out of them, but allowed all others to fester without any progress whatsoever, we would have substantially improved our velocity, or competitiveness, or team dynamic, or retention rate, or something similarly critical. Whereas if we allowed those few issues to go untreated, then even if we completely solved five others, we would still be unable to achieve our strategic objectives?

If that question is still hard to answer, then as a guideline I like the following order of precedence. That is, if you have a serious problem in some of these categories, I generally pick whichever comes first:

- Retention (if customers are leaving, the business model and product isn’t working)

- People (must have the right team)

- Throughput (can’t do enough strategic work per month)

- Growth (Details on how to tackle growth challenges)

- Competition

- Health of the code base

- Execution risk

A perfect formulation of a problem is already half its solution.

—David Hilbert

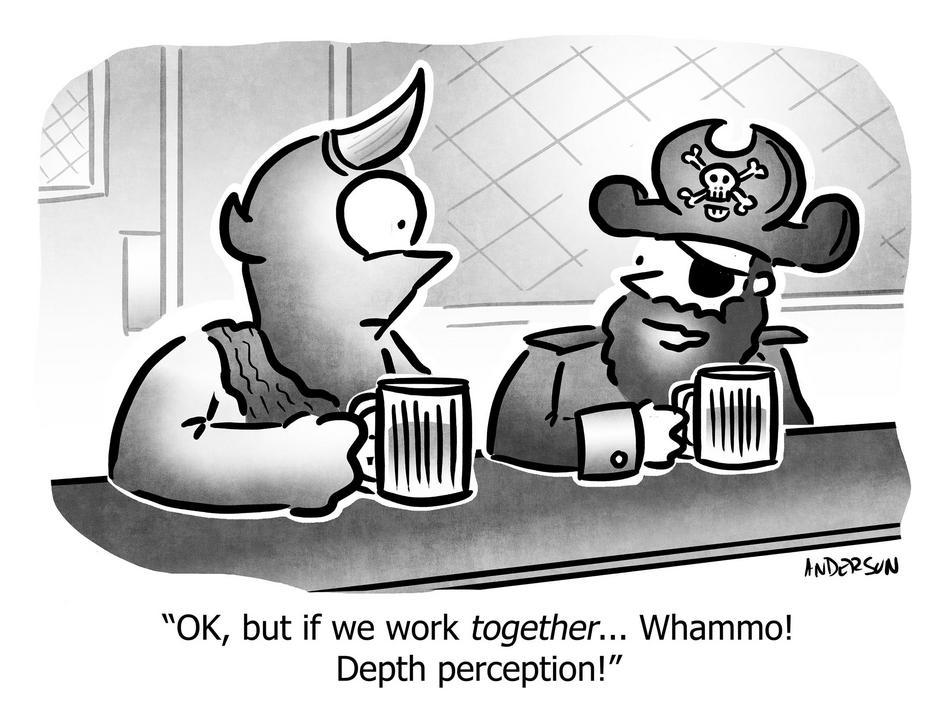

Main Activities

Narrative Plot Point

Here’s what we’re doing.

Guiding question

How do we overcome or side-step the obstacles, while advancing the strategic objectives, with our current people and capacity?

Why can’t we skip this section?

If you don’t select a few, large, impactful things to do (“Rocks”), you will wile away your time chipping away at incremental things, believing that you’re making progress because you are “agile,” but in fact not tearing down the obstacles nor achieving the objectives quickly enough.

While putting your finger on the crux of the challenges is often the most emotionally-difficult part, deciding what to do is the most intellectually-difficult. It’s hard to think of great ideas, and no framework or process magically causes you to be creative and insightful.

As with obstacles, you should start in “generation mode,” coming up with as many ideas as possible, before switching into “selection” mode, where you pick which ones to do. You should already have queues of ideas from around the company; if not, now is a good time to create some. If you’re having trouble coming up with creative ideas, use Extreme Brainstorming to shake things up.

If you’re having trouble figuring out how to deal with the obstacles, consider the parable of Herbie (from The Goal by Eliyahu M. Goldratt). A group of hikers are climbing a mountain. One hiker—Herbie—is constantly falling behind, preventing the group from achieving their goal of reaching the summit. There are three ways to deal with Herbie: (1) Leave Herbie behind; (2) Help Herbie get better; (3) Decide that you’re not going to achieve your goal. These options help you think of solutions; respectively: (1) Let that problem burn or ignore certain work that you’ve been assuming “must” be done; (2) Do extra work that mitigates the problem; (3) Change your objectives to something you can actually achieve.

Often the best solutions come from synthesizing several ideas. For example, often at WP Engine an idea that increases website performance for our customers also decreases our costs, because it takes less CPU time or fewer bytes transferred over the internet to accomplish the same end result. This is another reason to use things like Extreme Brainstorming; even if an individual idea is bonkers, it might be synthesized with a practical idea into a great solution.

For the final selection process I recommend the Binstack method, because you’re picking one or just a few critical big things to do. Your objectives and obstacles act as natural filters, immediately eliminating anything that doesn’t directly address those, but allowing yourself a few secondary prioritization dimensions.

You might be tempted to use an ROI analysis, but this is the wrong framework. ROI is good for smaller activities, where the goal is to find the “best use of time.” For your most critical pieces of work, the goal is not to optimize your time, but rather to maximize your impact on the most critical things.

See this Rocks, Pebbles, and Sand work-planning framework for a complete system that covers all kinds of work, including these most-critical activities and medium-sized work where ROI analysis is appropriate.

A successful solution to a problem makes the problem appear to have been nonexistent in the first place.

—James Surowiecki

Metrics & Indicators

Narrative Plot Point

Here’s how we’ll know whether we’re making progress, and when we’re finished.

Guiding question

How will we know whether it’s working? What is changing? What did we learn?

Why can’t we skip this section?

It’s easier to avoid accountability, believing that hard work and high throughput is the same as having an impact. Saying “focus on inputs, not outputs,” which is true when executing work but false if it means we’re not actually getting the outputs we need. We must not let ourselves off the hook, but neither should be measure ourselves against metrics we don’t believe in, or insist that all important things can be boiled down to a number.

The “Activities” are supposed to make progress on the objectives, but how will we know if that’s actually happening? They’re supposed to deflating the challenges, but are they really getting eliminated?

In the ideal case, we should measure progress with numbers that are objective, well-defined, measured daily, and have a clear “stopping-point” where we can declare victory. But we all know that most things we can measure aren’t so ideal, and sometimes the most important things aren’t a number.

To the extent that important things are numbers, use this KPI framework to decide what things should be measured, and as a checklist of what a “good” metric is.

For concepts that are not a number, capture their essence in writing. Make the language crisp and obvious not only inside the team but to outside stakeholders. Nowadays you can use AI to take a rambling audio description and turn it into a pithy statement. An example might be: “Be revered as the most innovative product in the category” or “Have the best social media content.”

These statements can be surprisingly powerful despite not being connected to a number. Even when people disagree later whether we’re making progress against them, those are exactly the right sorts of debates to have, because you’re sorting out how things are going, and whether you should make a change. That’s the point of metrics.

Not Doing

Narrative Plot Point

Here’s what we’re not doing (yet).

Guiding question

What do we really want to do, but we just have to wait so that even more important or urgent things can be done?

Why can’t we skip this section?

Decisions are about saying “no” even more than saying “yes.” Without articulating the “no’s,” the team is less focused, the decisions are less clear, and stakeholders wonder whether you’re even aware of the problems that you chose not to tackle.

The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.

—Warren Buffett

Deciding to do a few things always means deciding not to do dozens of other things.

“Well, not doing them for now” we like to say, to put the listener at ease. But actually, most of them are “not ever,” because we always have 10x more ideas than we have time to execute. That’s the lesson of every Jira backlog, feature-collection system, or prioritization spreadsheet.

When you don’t articulate what we’re not doing, it can appear that you don’t even know those things exist. Perception is reality. Stakeholders or even people on the team believe you’re ignoring important things, when in fact you’ve selected certain important things. You need to say that out loud.

It’s not just about proving yourself to an executive, it’s about reminding yourself and your own team, especially when a big customer complains about one of the things you’re intentionally ignoring, and the pressure is on, the emotions are high, and you need the resolve to stand firm on “no.”

You can do anything, but not everything.

—Derek Sivers

Next quarter, when you’re going through this process again, this is a great list to revisit. You’ll be surprised how many items seem less important now than before. And some might be more important; perhaps now is the time.

At WP Engine this a simple bullet-point list, just one line per bullet. It says what the topic is, and doesn’t even explain why it wasn’t selected. You could go further, explaining why each didn’t make the cut. You could go still further, creating a “Now / Next / Later” roadmap.5

5 Or, my personal preference in that three-column genre: “Now / Likely / Maybe.” This better indicates not only timeline but our confidence that those are even the right ideas. After all, how many of those “Later” items do you ever get to? If the answer isn’t at least 50%, then they’re not “Later,” they are merely a possibility.

Remember, this isn’t a random bucket of 100 feature-requests. It’s a list of things that are important, possibly even seem urgent, that you really do want to do, that maybe only barely didn’t make the cut. In short, these were the difficult decisions.

I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying no to 1000 things.

—Steve Jobs

Full Example: Tesla

The final result is clear and simple, hiding the complexity of the process that created it.

Let’s use Tesla as the example, because although it’s over-used, that means you’re probably familiar with it, and thus you can see how it all comes together:

Strategic Objectives

Tesla’s long-term vision is to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy through the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs).

To do that, we need to:

- Invent vehicles that are not only battery-powered but also desirable, because of their performance and safety.

- Create production lines that are scalable but also cost-effective, so we can be profitable.

- Generate excitement and loyalty by bucking consumer expectations that EVs are impractical and have low performance.

Obstacles

These obstacles stand in our way of achieving our vision:

- Intrinsic difficulty: Inventing new types of battery and production lines is near-impossible.

- Market Skepticism: Overcoming consumer and industry skepticism about the viability of EVs.

- Manufacturing challenges: Scaling up production to meet demand.

- Infrastructure: Lack of widespread EV charging infrastructure creates range-anxiety.

Main Activities

We will overcome these obstacles while achieving our strategic objectives by:

- Innovate in Battery Technology: The insight is that the battery is the key. Develop more efficient, longer-lasting, fast-discharge batteries.

- Direct-to-Consumer Sales: Bypass traditional dealership models to control pricing and customer experience.

- Scale Production: Invest in Gigafactories to massively increase production capacity, hiring specialists and investing with the insight that factories are not just a necessary step but strategically vital.

- Infrastructure Development: Invest in a network of Supercharger stations for convenient charging.

Metrics & Indicators

We know whether these activities are working through:

- Battery Cost and Efficiency: Measure improvements in battery cost per kWh and immediate-discharge rate.

- Vehicle Sales and Market Share: Track the number of units sold and market share in the EV sector.

- Production Capacity: Measure fully-completed cars/day per Gigafactory.

- Infrastructure Expansion: Number of new Supercharger stations operational.

- Consumer Delight: People absolutely love their Teslas, calling it a magical experience and never wanting a gas-powered car again. (not a number)

Not doing

We are intentionally not doing these valuable, important things, so that we can focus on the above:

- Safety and Practicality: Although we believe eventually we will make the safest sedans in the world, first we have to solve the challenges of batteries and performance, because those are the obstacles. We know that safety is a matter of good design, but we already know from existing EVs that if the car is safe, but not performant and low-range, then it will not be popular. So we have to solve those first.

- Affordable models: The company will truly scale and make the impact we want in the world, when it is accessible to most people. But at first, before factories are at scale, before the bugs are worked out, before all the costs are minimized, our cars have to be expensive. So we have to start out as a luxury brand.

- Expand to China: The second-largest market in the world, eventually will be the largest, and the first manufacturer there might have a decisive advantage. But it is its own special challenge, and we need a popular car that works before we jump into that pool.

Tesla is often lauded for having a clear strategy, and you’ve heard them report the metrics above as indicators of progress or success.

You need a plan that is just as clear. Each team needs one, and your company needs one.

Otherwise, you’re probably not working on the right things, and certainly not communicating what must be done, in a way that everyone can understand and implement.

Tell your story.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/strategic-planning/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF