Leverage Points

Every business has a few special areas where small changes in input have large changes in output. It is efficient to spend time and money in those places, winning an out-sized return.

If only you could identify what those Leverage Points are!

Ideally, everything important would be a number, precisely reported in real-time. Ideally, you could analyze flows like attraction → consideration → purchase → onboarding → active customer → cancellation. Ideally, you could run 100 tests simultaneously, with enough data points to identify subtle changes, repeated to eliminate the inevitable false-positives. Ideally, you could experiment in one area without affecting the data in another. Ideally, but sadly, rarely.

Fortunately, I have found that most companies share a few common points of leverage. They are common because they exhibit some natural mathematical leverage that applies to many business models.

Therefore, if you’re part of the non-ideal majority, you can be confident that focusing on one or more of the below will have a large effect on your business.

Pick one?

Top of funnel

What if your marketing were so perfect that only the only people who clicked your ads were ideal customers from your target market? People who already feel the pain you solve, identify with the way you talk about it, want the specific set features you currently offer, have an allocated budget that exceeds your price, and are wanting to purchase today.

In this scenario, even a mediocre website, an imperfect conversion funnel, and a talentless order-taking sales team would convert most of these folks to a sale, simply because they’re the right people. This already demonstrates that the top of the funnel is a Leverage Point: The system works well, even when so much else goes wrong.

Now consider what actually happens in many companies. The direct-marketing group is tasked with “increasing traffic.” So they pay for traffic that turns out to be lower quality than usual. You might think that, while this is a less-efficient use of money, it’s fine, because some of that new traffic will become customers, and the rest will get filtered out by the rest of the funnel. But reality is far worse.

Lower-quality traffic decreases website-conversion rates. The website-conversion team now has trouble measuring their long-term success at improving their metrics. While you might think that a single A/B test won’t be affected (because both sides of the test experience the same lower-quality traffic), in fact it is affects, because finding “winning” variants will require appealing to low-quality leads, rather than appealing to the ideal lead who will actually become a customer. So this means they’re doing a poorer job converting the ideal customers, and a better job passing the wrong customers through to the next step of the funnel, where either sales teams waste time in pointless sales calls, or short-term cancellation increases as customers figure out for themselves that the product was never a good fit. All of it wasting customers’ time, wasting employees’ time, wasting company’s money.

“Optimizing” one step in the funnel for quantity or conversion rate, rather than for quality, affects all downstream steps. Therefore, small changes in the quality of the first step in the funnel has a dramatic, out-sized impact on the effectiveness of the entire company. This is leverage.

On top of that, it breaks our ability to learn and improve with the right customers. The web team can’t optimize for the right customers, because their tests are polluted with the data from wrong ones. The product team can’t tell which feature requests come from good customers as opposed to people who should never have been customers, pulling them in the wrong direction. Tech support spends time with hopeless cases instead of thrilling customers who want to be here for the next ten years, and can’t analyze what topics are worth addressing in the product. Finance can’t report the metrics we need—CAC, ARPU, NRR, cancellation—because the true numbers are mixed with garbage numbers. Sins at the top of the funnel infect everything else.

Marketing funnels aren’t the only systems that exhibit this effect. Consider a company who says they “only hire the top 1%.” Not true. At best, they hire the top 1% from the resumes they saw. Surely, many of the actual “top 1%” people never applied. And just as surely, the definition of “top” is unclear, and the ability of an interview process to correctly discern which people are “top 1%” is dubious. So, what is the truth?

The truth is, if you’re sourcing from a pile of fantastic applicants, then your interview process and your talent discernment doesn’t matter. You’ll hire good people regardless, even by accident, even if you pick at random. Whereas, if your applicant pool is weak, than even the best discernment process in the world will still not result in strong hires. The best people were never there.

Or consider angel investors, who talk to companies that are seeking funding, typically before the company has much evidence that it will work. The angel tries to select the “best bets” from the set of companies they see. “Best bets” is in quotes, because angels are famously terrible at picking winners. The median angel loses money,1 and even the top angels in the world still have more failures than successes. An investor who sees nothing but stellar opportunities will build a decent portfolio almost regardless of which companies they back. Whereas, an investor with bad “deal-flow” (as it’s called) will not succeed, even if they pick the best companies from what they see.2

1 Even among professional venture capitalists, 65% lose money, and only 10% generate returns high enough to justify the risk and illiquidity.

2 This also explains the persistence of top venture firms. Once a firm establishes a stellar reputation, the best founders will proactively seek them out, resulting in great portfolios almost regardless of their ability to pick. This is not undeserved; successful firms also attract great people to work there, and by all accounts really do help companies get to the next level. Nevertheless, their continued good results is made possible by (earned) deal-flow more than their ability to select individual winners. More evidence of this: Looking backwards from successful IPOs, software companies are typically backed by one of a few well-known firms, yet other well-known firms passed on those same deals. It didn’t matter which firm said “yes.”

So, “top-of-funnel-quality” is a Leverage Point in any funnel-like systems, which applies to any such process in any company.

Pricing

You already know price is important, but you might not realize why it is nearly always true that small changes in prices—in either direction—have an outsized impact on the business.

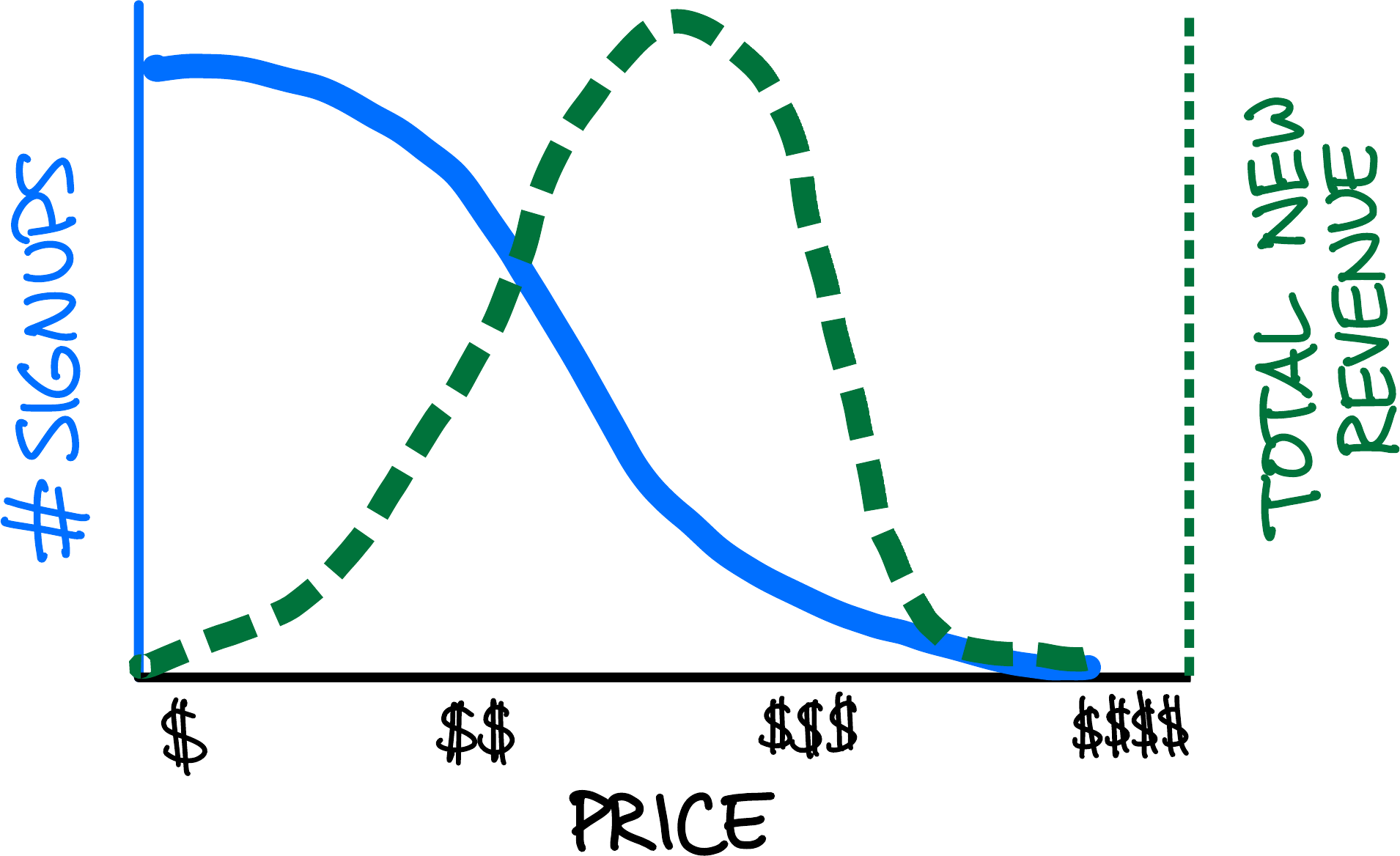

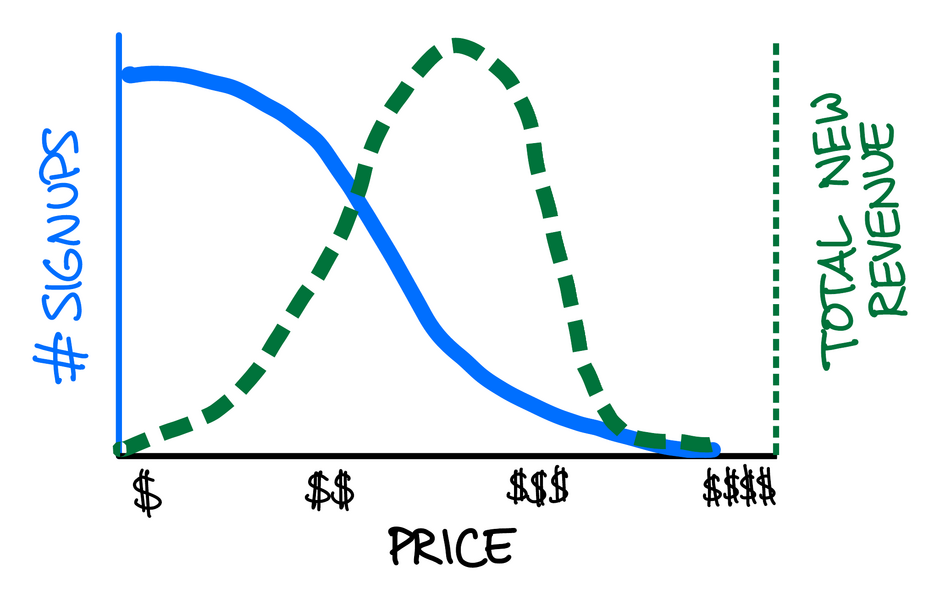

In microeconomics you learn the relationship between price and sales: If you increase price, you decrease the number of people “willing to buy,” but each one is giving you more money. So the question is: Is the increase in revenue from higher prices big enough to compensate for the fewer sales? If yes, the economist would say your prices are “too low,” else they are “too high,” and ideally you hone in on this sweet-spot maximum amount of revenue:

Figure 1: As price increases, fewer people buy. Total revenue is signups multiplied by price, creating a natural maximum that economists insist we seek.

In reality, this is rarely how it works. (Economic theory often fails to predict the real world.) In reality, even small price changes sometimes cause sales to drastically fall off a cliff or, especially in early-stage startups, increases in price counterintuitively lead to an increase in the number of signups:

Figure 2

Why? Because price isn’t independent from the product or the target market; indeed, price is a main determinant of your target market and your business model. Therefore, changing price can mean changing the target market, which changes everything.

Clearly, a large change in pricing represents a large change in strategy, positioning, target market, and customer expectations. But the question here is whether small changes also have large outcomes, contrary to micro-economic theory.

There are three possible results from a small price increase:

- (1) Has a measurable (i.e. large)3 negative effect on new customers per week.

- You are in a highly competitive market without significant, valuable product differentiation. Because if it weren’t competitive, customers wouldn’t have an alternative, and if your product were differentiated, they couldn’t select an alternative and still get what they want. Therefore, there are two actionable conclusions:

(a) Lower your prices. You’ve demonstrated that the micro-economic model is correct in your case, so you can not only get more revenue from lower prices, you also get more customers. “More customers” is always better, all else being equal (though “all else” is never, in fact, equal). It means more people recommending you, more product feedback and insights, more momentum, lower impact when one customer leaves, and fewer customers for competitors. Warning: Don’t lower prices so much that you change your target market, unless you’re intentionally making a strategic change. Blindly competing on price is dumb, but strategically competing on price can be brilliant.

(b) Create differentiation. There are many possibilities.4 Perhaps your product is, in fact, unique, but you’re not effectively communicating that. Maybe your product is unique in aspects that customers don’t value. Maybe you need other advantages of Love and Utility, like having a higher purpose that customers want to support. Most likely, you need to face the truth that your product really isn’t special in a significant way. - (2) Has no measurable effect on new customers per week.

- In this case, slightly raising prices is a pure win—more revenue, more profit. The reason this is also an outsized result, is that it increases profit non-linearly. Suppose a business charges $50/mo and nets $5/mo per customer after all expenses. Raising prices even just to $55/mo nets $10/mo. That is: a 10% increase in price resulted in a 100% increase in net profit. That is the definition of leverage.

Your next task is to raise prices a little more. Raise until something changes—you’re no longer targeting the right customer, signups fall off, or some other clear signal that you have in fact found your optimal price. - (3) Has a measurable (large) positive effect on new customers per week.

- As shown earlier, this can happen, and even the possibility of it is reason enough to try. Obviously you should keep that pricing, and like the previous case, your next step is to keep trying raises until something significant changes.

It is quite likely (though not certain) that this also indicates you were incorrect about your target market. Customers apparently have budget, urgency, and pain-points that are significantly different than you thought. The reason the numbers are moving contrary to economic theory is because you’re tapping a new customer segment, carrying different dynamics. Great news, but you need to dig into “why” just as fervently as if the result were negative, so you can learn what your customers are really like, what your target market really is, and then how to update your strategy and product. And congratulations, you’re probably at Product/Market Fit.

3 Because statistical-significance is hard, especially with relatively low N that even established companies might have in weekly signups, here the word “measurable” also implies “large.” And by assumption the change in price was small.

4 This great article by Ton Dobbe details many of these possibilities, how to identify them, and what to do about it.

No matter the result, you have to find out.

Cancellations

It’s almost impossible to get a customer.

They had to hear about you, whether through the white noise of social media or the labyrinth of organic search results, or desperate advertisement, all of which has never been more saturated and engineered. They had to click through to your website. They didn’t bounce off in 3 seconds. They actually read something. They understood what you offer. They decided it might work for them. They were unfazed by the pricing page. They didn’t immediately reject you after comparing with competitors. They signed up. They entered a credit card number. They on-boarded themselves, configuring things, entering data, finding early success. They invested hours. They engaged with support. They really wanted it to work.

And then, after all that, they cancelled.

Even without the financial argument, this is already enough to know that understanding cancellations must be one of the most critical things you can do. If the customer was willing to do all that, and still your product fell short, you have to understand why.

Maybe you promised something you’re not delivering on. Maybe you did deliver but the product wasn’t intuitive enough for them to figure that out. Maybe the product is useful on day one but not day one hundred. Maybe the target market can’t really afford it or isn’t really serious. Maybe you’re asking the customer to make changes they can’t make. Maybe your competitor is better at product and proactive marketing. Maybe bugs or gaps are pushing them away. Whatever it is, you have to find out, and make changes.

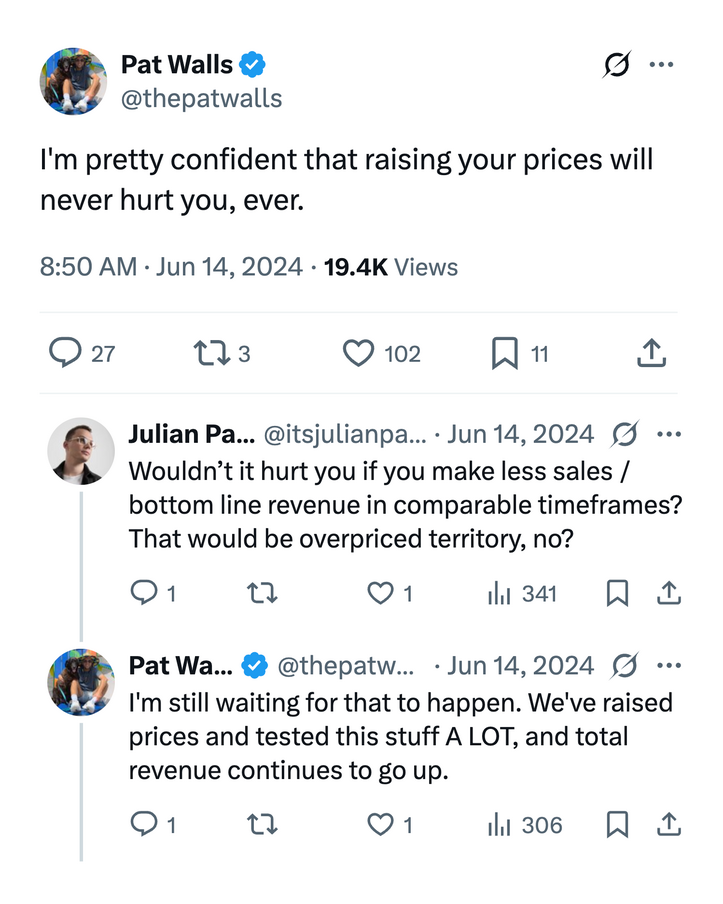

And then there’s the financial argument, which proves that it’s not just critical for product, it’s a Leverage Point, because small changes in cancellation rate result in large changes in revenue. The reason is simple: Cancellation is exponential, but nothing else is; specifically, marketing is not. Cancellation is exponential because it’s proportional to the size of the company, which is why it is measured as a percentage, e.g. “7% per month.” Marketing is measured as leads per month and ROI per leads. The bigger you are, the greater the effect of cancellations (in absolute dollars), but running ads works the same regardless of your revenue or customer-count.

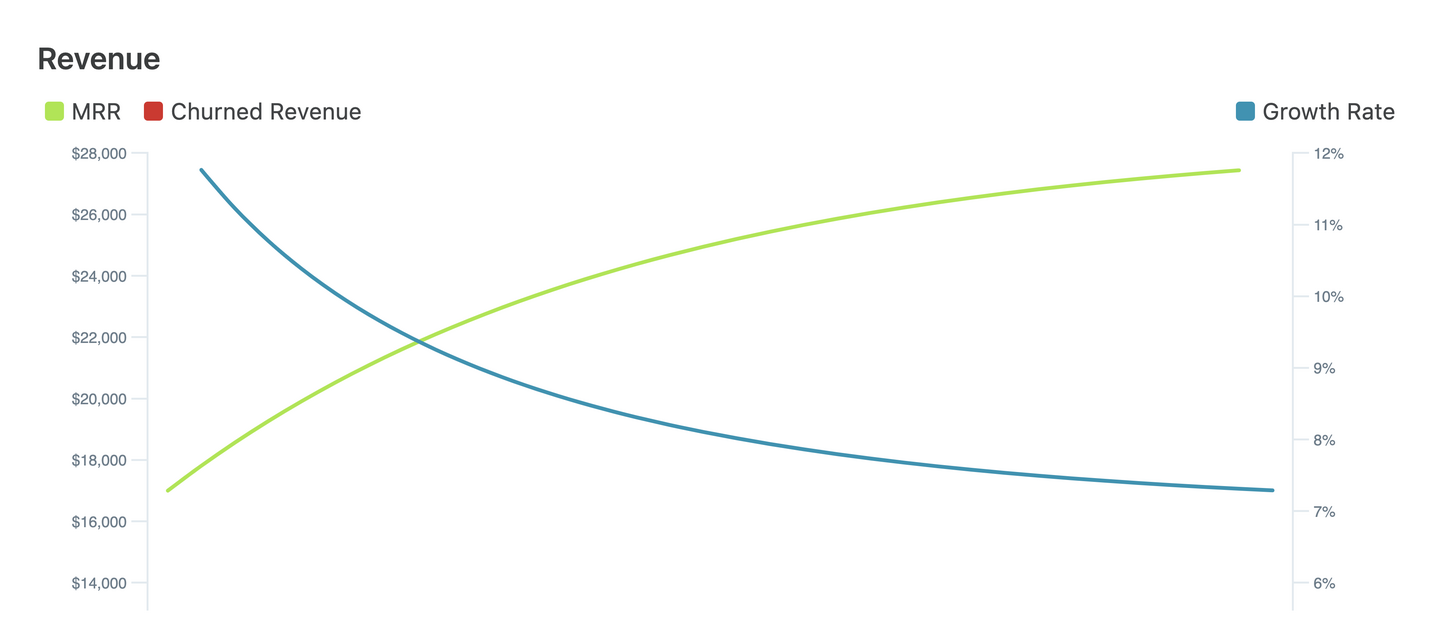

Making this concrete: With $15k MRR, adding $2k/mo of new customers—a healthy 15% per month growth rate—a 7% cancellation rate means already half of that growth is negated by customers leaving. The company barely got started and already its growth is being decimated. At that rate, only one year later, having grown to about $27k MRR, the company has stopped growing completely (Figure 3), despite spending time and money on marketing and sales.5 Don’t forget—those new customers cost money to attract, sell, and on-board with tech support, but all the value of that expense is negated by an equal number of customers walking out the door.

5 Growth stops because the $2k of new customers arriving in a month are negated by $27k × 7% ≈ $2k customers cancelling in that same month.

Figure 3: Charting adding $2k/mo new MRR with 7%/mo.

As described in detail in this article on how to calculate your maximum MRR, changing your cancellation rate has a large impact on growth rate and how large you can ever grow. In our example, moving from 7% to 5%/mo increases our maximum MRR by 50%, to $44k. That would enable use to hire two people, or spend more on marketing to increase that $2k/mo. It would dramatically transform the company’s capabilities.

Whether you’re swayed by the math or the product or the thought of being rejected by customers, lowering cancellations is almost always a high-ROI activity.

Onboarding optimization

Starting with the chain of events from the previous section, stopping at the “onboarding” phase, we find another common Leverage Point.

A common mistake in analyzing customer retention is to look at total retention across all customers. Instead, look at retention based on the age of each customer, by month or even by week. You will find a large drop-off in the first 2 or even 10 weeks, followed by relative stability. This is the difference between customers who successfully on-boarded and customers who have settled in. When you see the stark difference, you realize they are totally different beasts, which means you need different metrics and different actions.

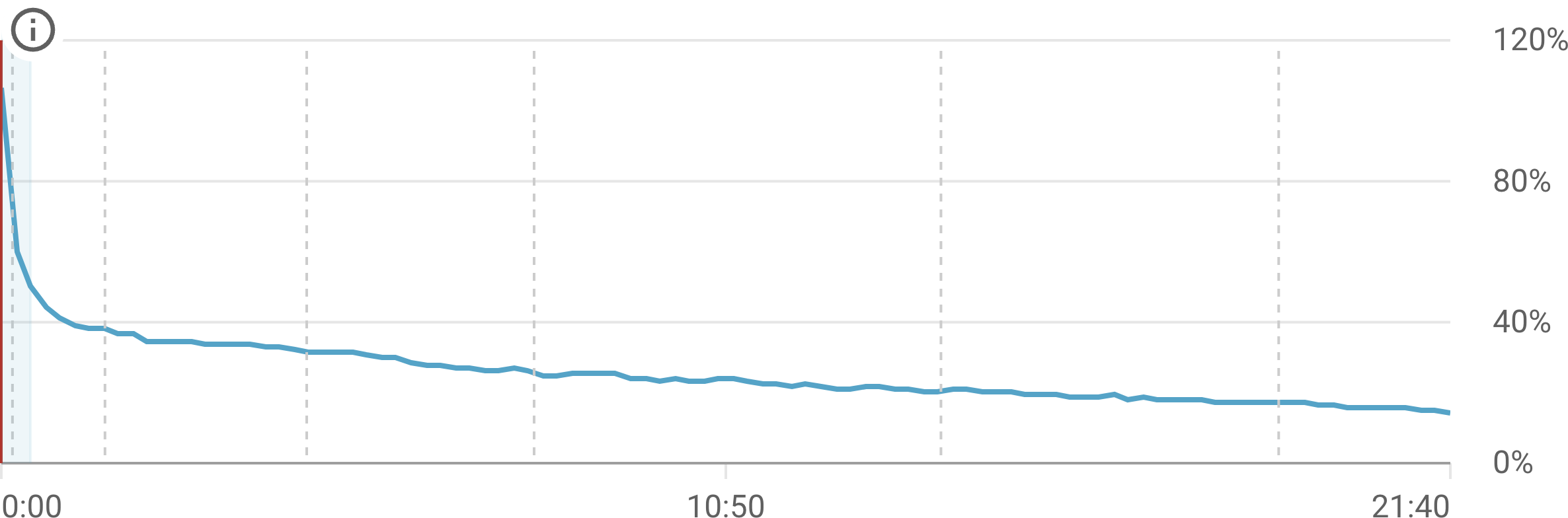

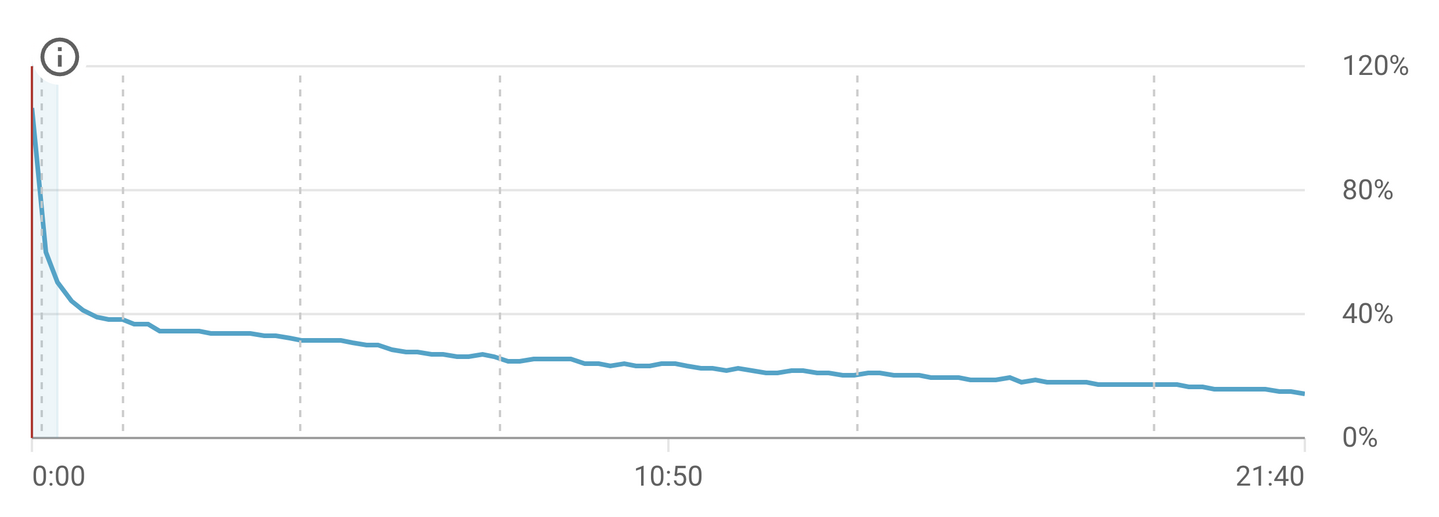

It’s not just SaaS products. Consider this chart of how many people are still watching my YouTube video about the Profit Whale Curve (Figure 4). 20% of viewers made it past 20 minutes—pretty good for brain-rot YouTube viewers. But 50% dropped off after merely 30 seconds! If you watch, you’ll notice that my hook isn’t great, and then I waste time with an indulgent joke about constellations—not cute enough to hold people’s attention. I can improve.

Figure 4: Only 50% of viewers are still watching the video after 30 seconds. Another 50% survive the full 22 minutes.

If I shift that number from 50% to 55% (10% improvement), it’s possible that viewers-until-the-end could shift from 20% to 25% (25% improvement). Leverage, and a better video.

This also applies to SaaS products. Early in Hubspot’s life, they realized that new customers who watched their on-boarding instructional videos were far more likely to still be customers after six months. So, they started enforcing an onboarding training hour as part of their sales process, shifting their monthly churn rate from 3.5% to an incredible 1.5%. Hubspot investor David Skok witnessed similar transformations at other companies. Better on-boarding also decreases total support contacts and increased customer happiness.

Onboarding is also when customers are most engaged and receptive. They’ve just committed to your solution and are motivated to make it work. This psychological opening closes quickly—within days, not months.

There are too many benefits to ignore. Onboarding is a Leverage Point.

Website optimization

Every marketing channel you invest in—whether it’s PR, social media, paid ads, or word of mouth—funnels through your website. Therefore, any improvement to your website’s conversion rate multiplies across all your acquisition efforts. A natural Leverage Point.

Beware the common claim that multiple improvements compound. The usual argument goes like this: A 20% improvement in your home page headline, a 15% lift from a better “Try Now” button, and a 25% increase from a clearer pricing page doesn’t add up to 60%—it multiplies to a 75% overall improvement in conversion rate. While this sounds logical, the real world doesn’t work like this. The reason was given earlier: When you improve one point, you affect other points, because you’ve changed who arrives there.

Another mistake in the typical advice is that small aesthetic changes can have big results. Sometimes they can, but large changes are more likely to have large results. Changes in positioning, attitude, language, consistency, and alignment with the target customer. This video shows an interesting real-world example:

Figure 5: Watch on YouTube

However, even a 20% improvement in website conversion yields a 20% increase in growth rate and a 20% decrease in the cost to acquire a customer. This double-win makes even small improvements extremely valuable; the definition of leverage.

To earn that 20% improvement, create theories about what customers from certain inbound sources are thinking, what they want to see, how they want to see it, what they want to do next, and then use A/B tests to disprove or hone those theories. This article explains how, and also why you must do this rather than the usual “throwing shit at the wall and seeing what sticks.”

Honorable mentions

There are more areas that have enormous impact for most companies, but that typically require more than just a small change. While these might not completely qualify as a Leverage Point, they are worth your consideration:

- Prioritization

- Different from productivity; if you run fast in the wrong direction, it’s still wrong. Therefore, it is enormously impactful to improve your ability to collect ideas, prioritize different work differently, and focus on the most impactful things.

- NRR

- Net Revenue Retention (NRR) refers to the growth of existing customers—upgrades, downgrades, and cancels, but not new customers. When it is positive, it means the company is growing even without marketing; this dramatically changes the growth curve, as much as cancellation alone. The reason it’s here, is that often making changes here are not easy or small, as it involves significant new tiers or new products.

- Pricing terms

- There’s the price, and then there’s how you charge. Annual pre-pay can transform the cash-flow of the business. Understanding budget limits can be the difference between a customer believing the product is actually $0, or conversely can be so annoying that they just buy a competitor instead.6 Buying out a competitor’s locked-in contract can win larger customers. Payment plans can win smaller customers. Including services which are relatively inexpensive for you can win deals. Trading a lower price for strong public testimonials or beta-testing can pay for itself a hundred times over.

- Channel power laws

- Many acquisition channels follow a power-law where the top 1% yields 20% or more of the results. The top Google ad or the top organic search result gets twice the clicks of the next. Top affiliates generate more customers than all other affiliates combined. In these cases, getting a top result has leverage, but playing in the long tail might not be worth your time at all.

- Team

- The best teammates increase everyone’s productivity, improve morale, contribute to culture, and make work fun, even when you’re tackling existential crises. That goes for management too.

- Purpose

- Having a purpose—whether as a result of execution or as the raison d’être for the company—motivates both employees and customers, keeps customers who otherwise would have cancelled, aligns strategy, and improves morale.

6 This happened to me; here’s that story.

The general idea is simple: Your time is limited, so you must focus on high-leverage activities. Details will of course depend on circumstances, but if you tackle one of the themes in this article, it will almost certainly be a good use of that time.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/leverage-points/

© 2007-2025 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear Simple eReader (Kindle)

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF