What to do when growth tapers off

Every company hits a frustrating phase where growth tapers off, or levels off, or even declines.

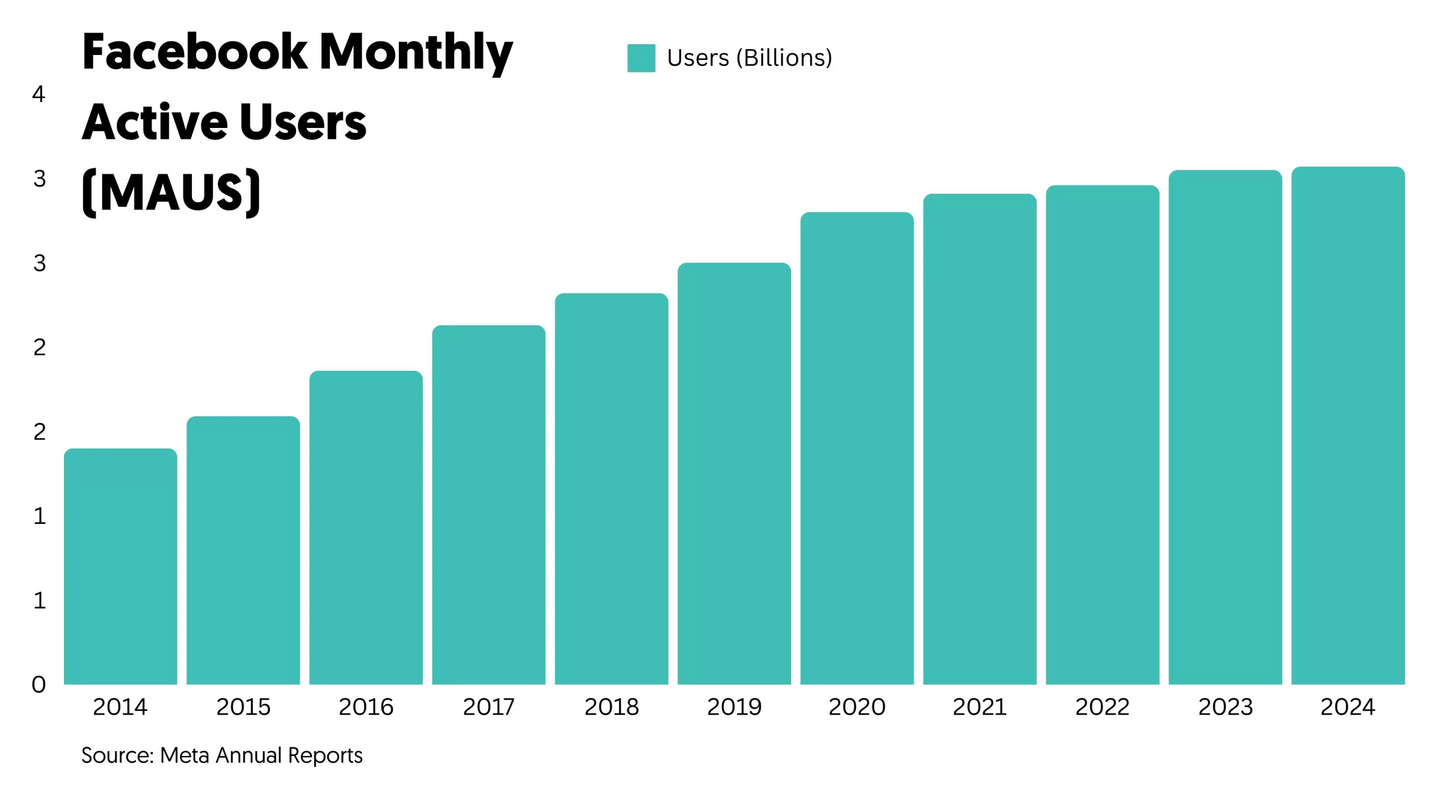

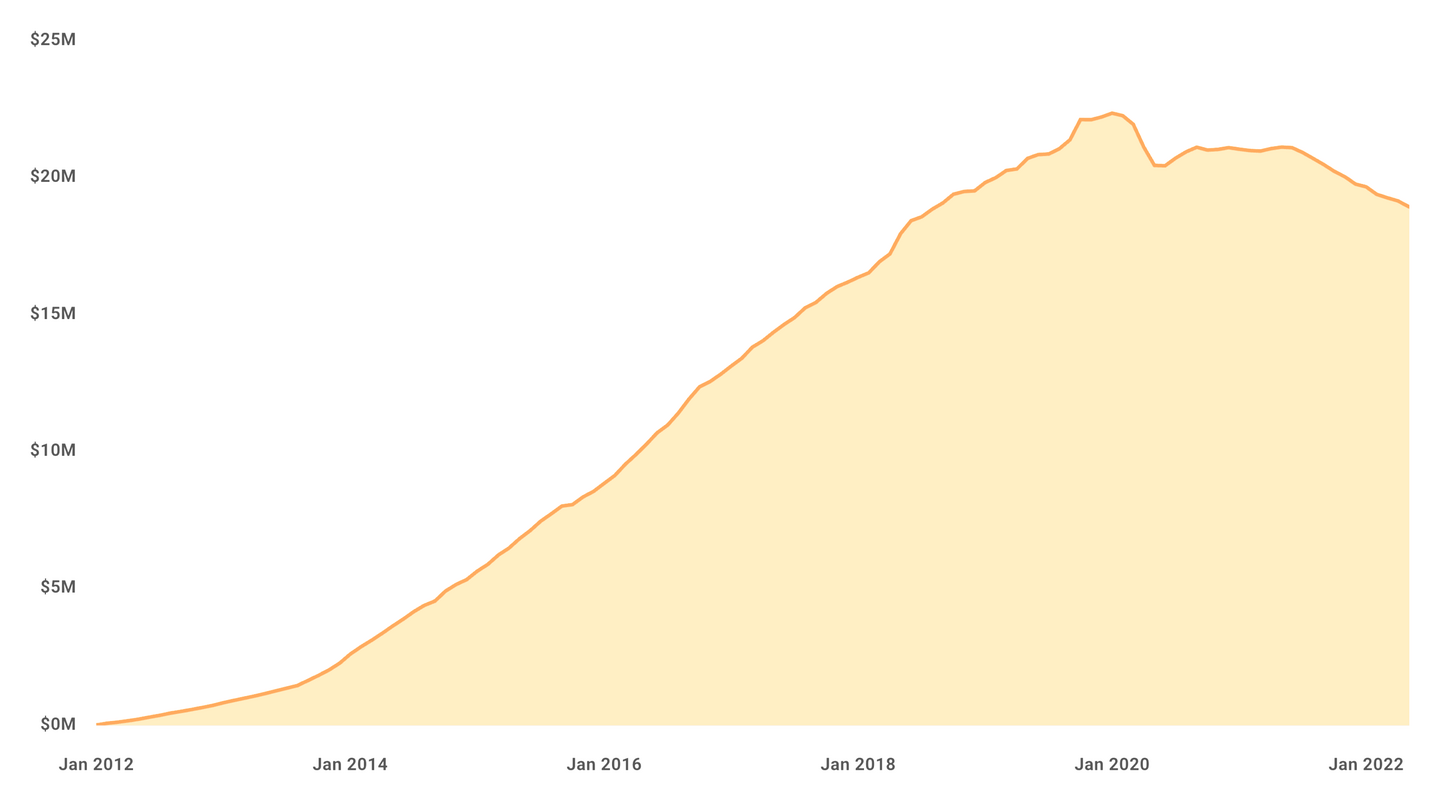

It happens whether you’re the most popular “viral” social media company in history (Figure 1)…

Figure 1

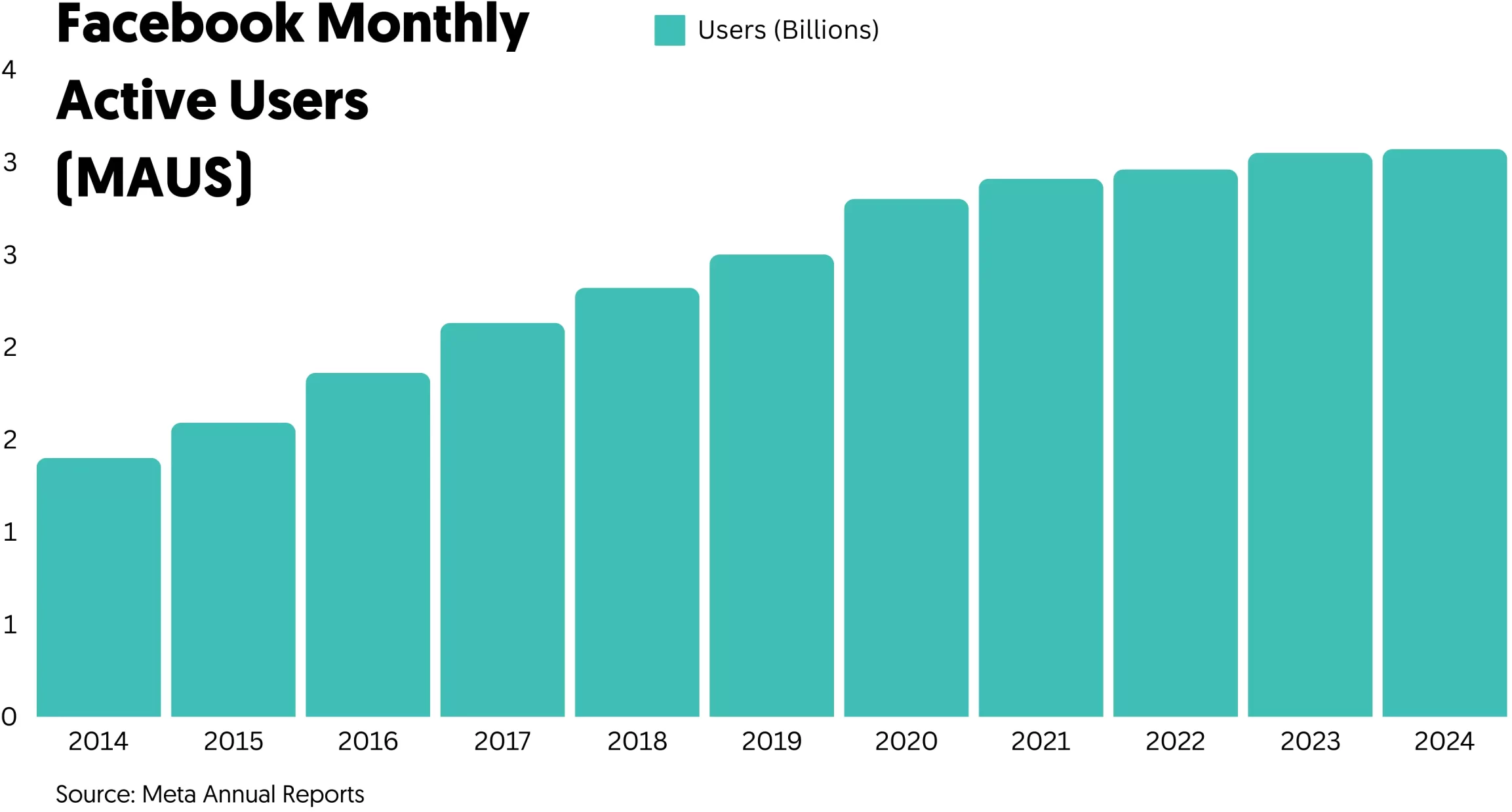

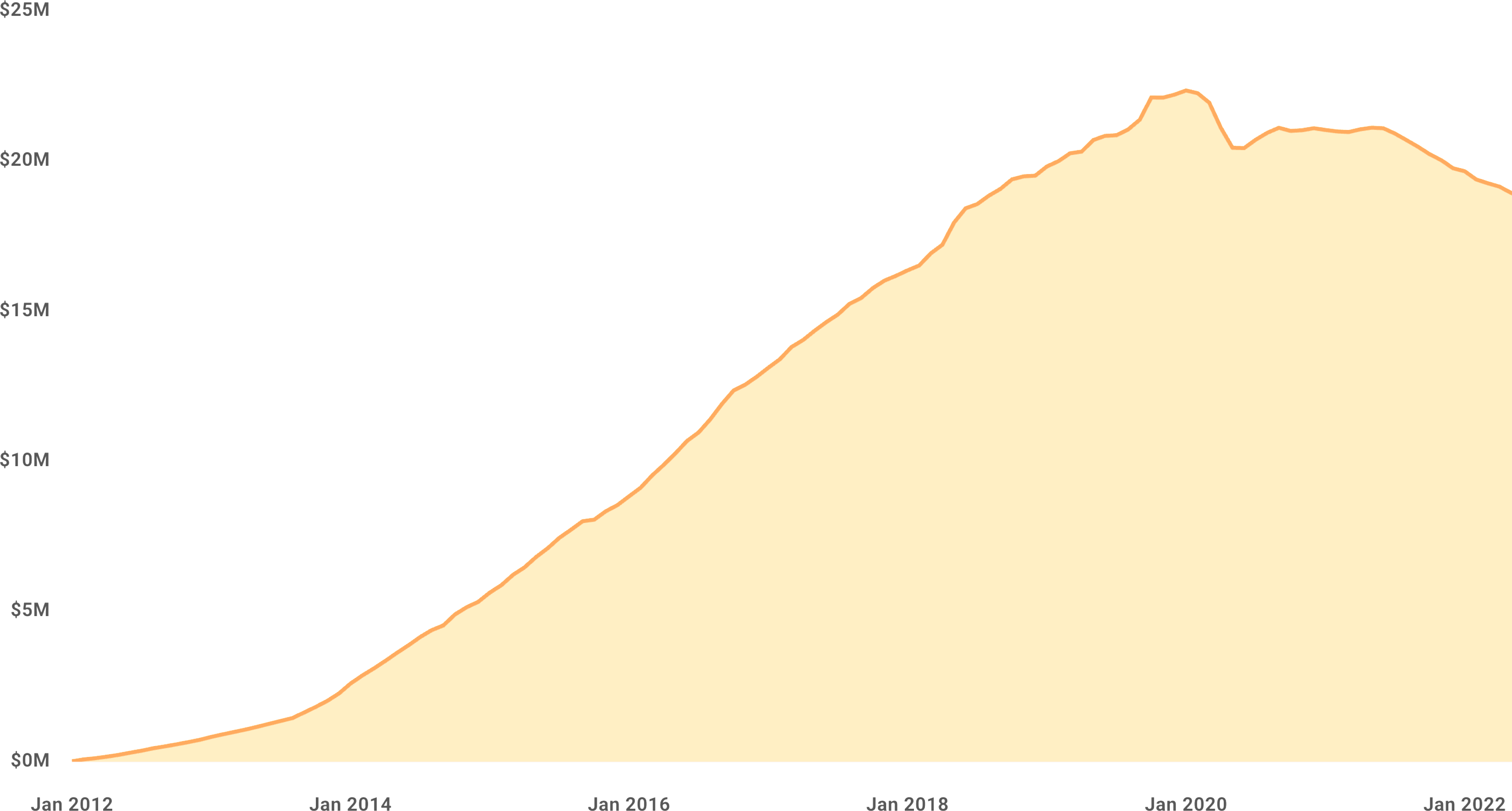

…or one of the most-respected bootstrapped, transparent, customer- and employee-first companies in history (Figure 2)…

Figure 2: Buffer’s ARR

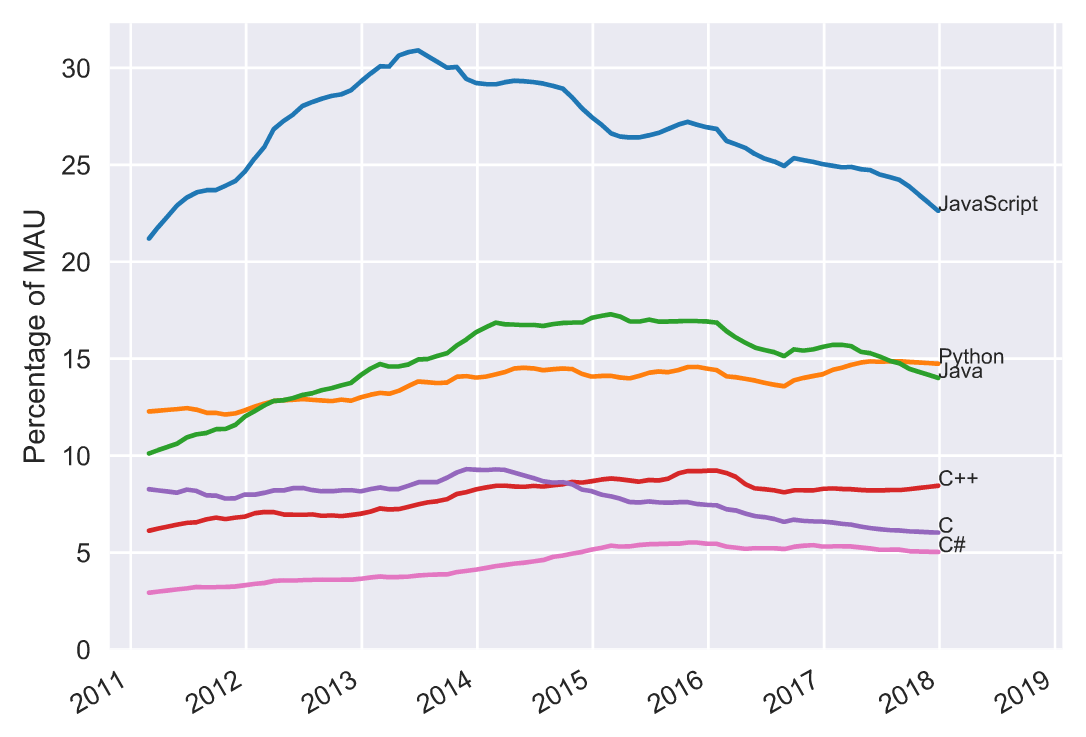

…or a programming language used by millions of people (Figure 3)…

Figure 3: MAUs of major programming languages as a percentage of all developers

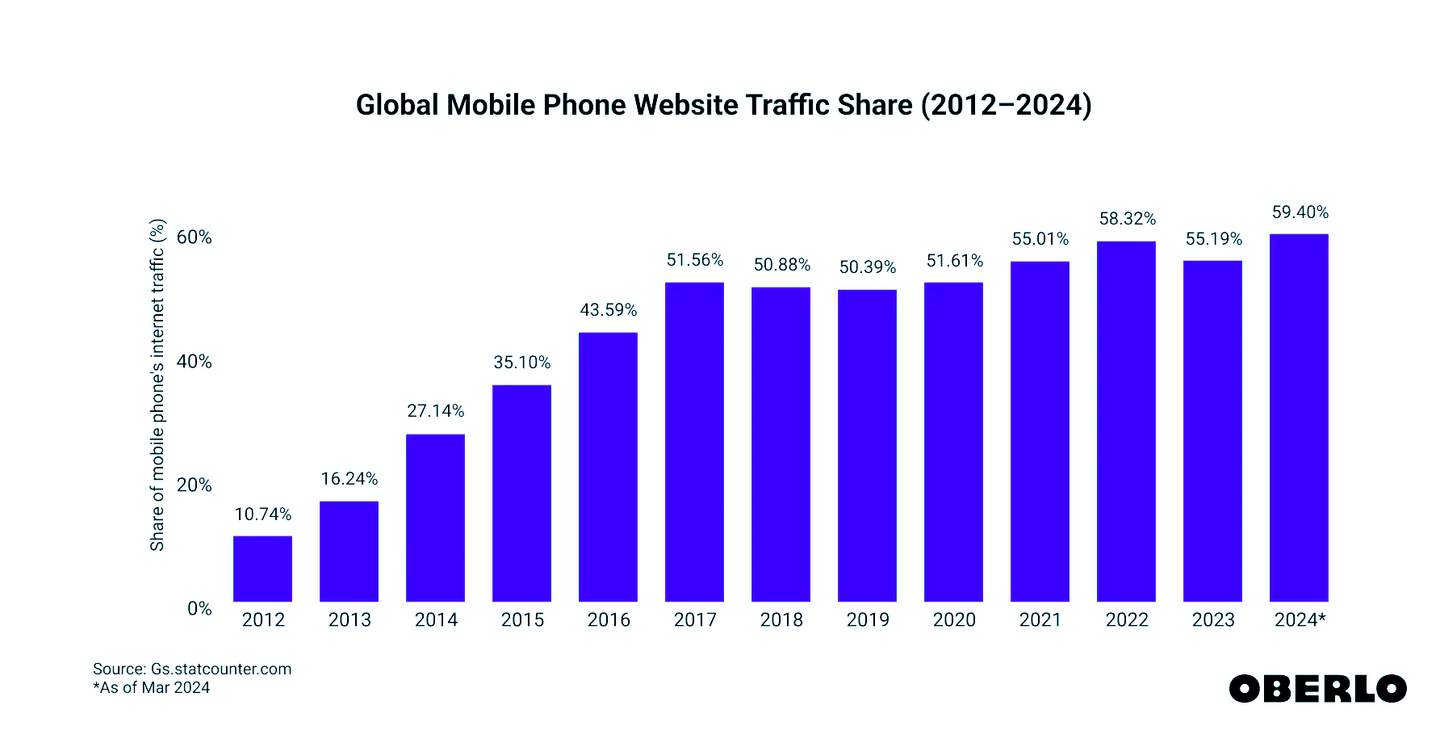

…or people switching to mobile devices (Figure 4)…

Figure 4

The founder protests! This shouldn’t be happening because:

- The product is better than ever (more features, fewer bugs)

- The market is bigger than ever (more potential customers, more money being spent)

- Our brand is stronger than ever (more customers, more presence, more time)

- We’re smarter than ever (more experience, more data)

And yet, it’s happening.

How do you fix it?

What definitely won’t work, is doing (more of) the same things that got you here. Nor doing incremental things, because this is not an incremental challenge.

Rather, you need to diagnose the most significant force causing the asymptote, and attack that force with non-incremental effort.

To beat the plateau we have to do things that we had previously considered out of bounds.

—Laura Roeder

I use the following framework to diagnose the underlying growth problem, whether it’s for one product-line inside WP Engine, or for top-line revenue at another startup.

I ask the following questions, in this order, stopping at the first question that identifies a problem. These are ordered by causal power; that is, addressing a lower one will not solve the growth problem, if there’s a problem higher up the list.

Q1. Logo Churn: Are customers leaving?

“Logo churn” is the corporate way of saying “churn measured by number of customers.” Not by MRR, not looking at upgrades, just the rate at which customers are leaving.

Sidebar: Calculating “churn rate”

A typical rate is “percent of customers lost per month,” which at its simplest iswhere

is the number of customers who cancelled during that month and

is the number of customers at the start of the month. However this doesn’t handle customers who signed up but then cancelled within the month. Therefore, it’s better to either (a) include sign-ups using

where

is the number of new customers added during the month, or (b) ignore those in/out customers, tracking that quantity separately (because you probably want to do something different about it!), and calculating

where

is number of customers who were present at the start of the month who cancelled within that month.

Logo churn is the worst problem because almost nothing else you do will make up for it. The customer is gone; there’s no chance for recovery. This is often correlated with negative reviews and negative social proof, hurting future growth as well—a double negative.

The worst part is that customers are saying “I don’t want this.” That’s a fundamental problem transcending “finance” and “business model,” piercing the heart of what you’re doing and why. If customers don’t want the product, nothing else you do matters.

You made a promise that customers wanted—that’s why they bought. But you didn’t keep your promise—that’s why they left.

Dangerously high logo churn rates are:

- B2C: 5%/mo

- B2B, Small Business: 3%/mo

- B2B, Mid-sized Business: 2%/mo

- B2B, Enterprise: 0.8%/mo

Small business owners love to push back on this, insisting that their 7%/mo churn rate is “normal for the industry” and “fine because we’re a small company” and “hasn’t been a problem so far.”

Incorrect. And, because they refuse to understand why 7% churn is high, they’re mystified at why it’s so hard to grow.

The math is simple. To see exactly why this is wrong, see the “High Cancellation” section of this article for an analysis of the specific case of Buffer (above), and why high cancellation (5%, in their case) is the one and only cause of their revenue ceiling. Here’s the summary:

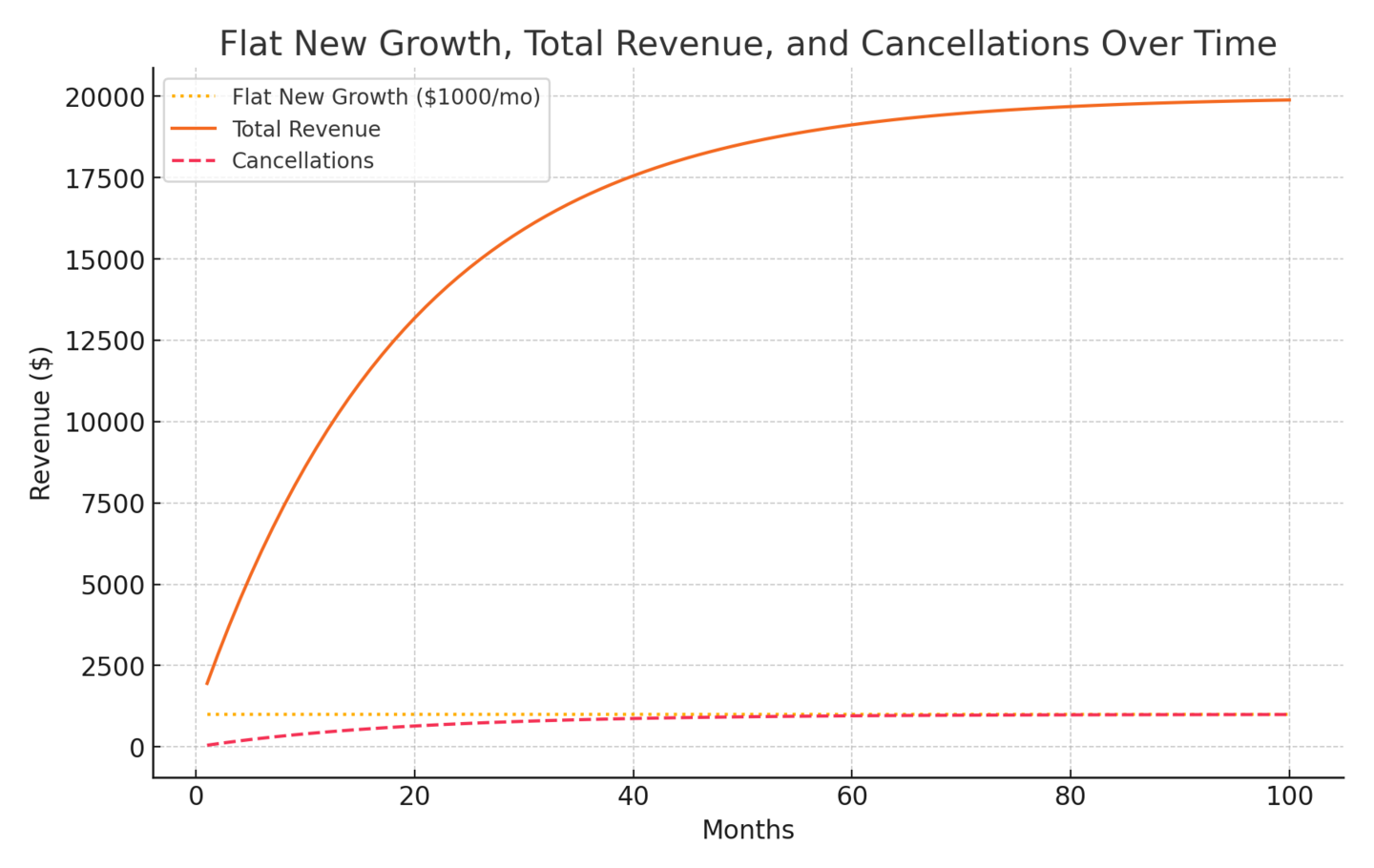

Figure 5: Buffer’s unit economics; new-MRR reaches a natural maximum of new-customers-per-month, whereas cancellation never stops growing in absolute dollars, because it is proportional to the size of the customer base.

The math is undeniable, as is the issue that customers aren’t reliably getting enough value from the product. This is a fundamental product problem that must be solved.

How?

You’d expect the answer to be: Talk to people who have churned, or are churning now. Unfortunately, they typically don’t want to talk—they don’t want to invest more time with you, and are often unhappy or otherwise emotional. Even when you do communicate—whether live or by survey—they often give a generic complaint (e.g. “not enough value” or “too expensive”) instead of the real reason. Why not? Because it’s easier, because they don’t want to hurt your feelings, because they themselves haven’t analyzed it carefully.

To see why these answers aren’t useful, consider “too expensive”. Remember, they signed up for the product, at this price. It wasn’t “too expensive” then. Which means “too expensive” isn’t the reason. It means there was some expectation that wasn’t met; they were happy to pay that price for something. What expectation did they have, which failed to deliver? The product didn’t work the way they thought? The product didn’t do what it promised? They used the product incorrectly? They were never the right customer for it? The product didn’t fit into a workflow? Their business changed? Your champion left the company?

At minimum, you need a thoughtful interrogation that gets to the root of the issue. Few (ex) customers will participate in such an activity; cherish those who do, and spend enough time with them honestly rooting out the issue.

Better: Look for signals that a customer is not being successful before they cancel, so you can reach out while they’re still ready to talk. That means understanding what is correlated with cancellation, and what is anti-correlated with retention (because all customers have some behaviors in common).

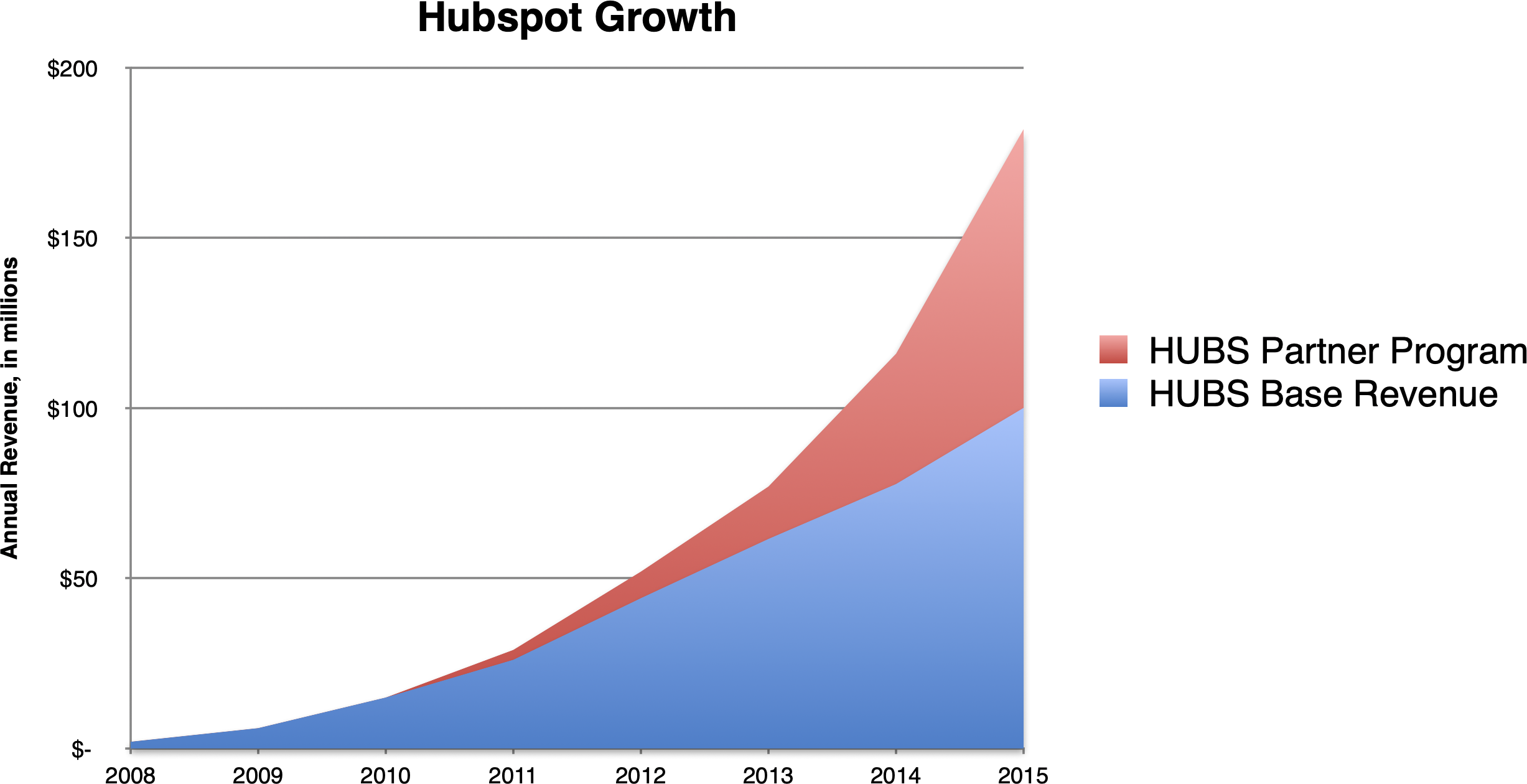

Finally, remember that “retention” is something everyone in the company has a hand in, and thus needs to diagnose and address. If marketing attracts the wrong customer, churn will increase. If sales force-closes customers who aren’t a fit, churn will increase. If support lets people down, even in the feeling of the interaction, churn will increase. If the product isn’t intuitive or doesn’t fulfill the promise, churn will increase. Early in their journey, HubSpot addressed even more areas to halve their churn rate, which converted them from “barely holding on” to a “growth juggernaut.”

This is difficult, but worth the effort.

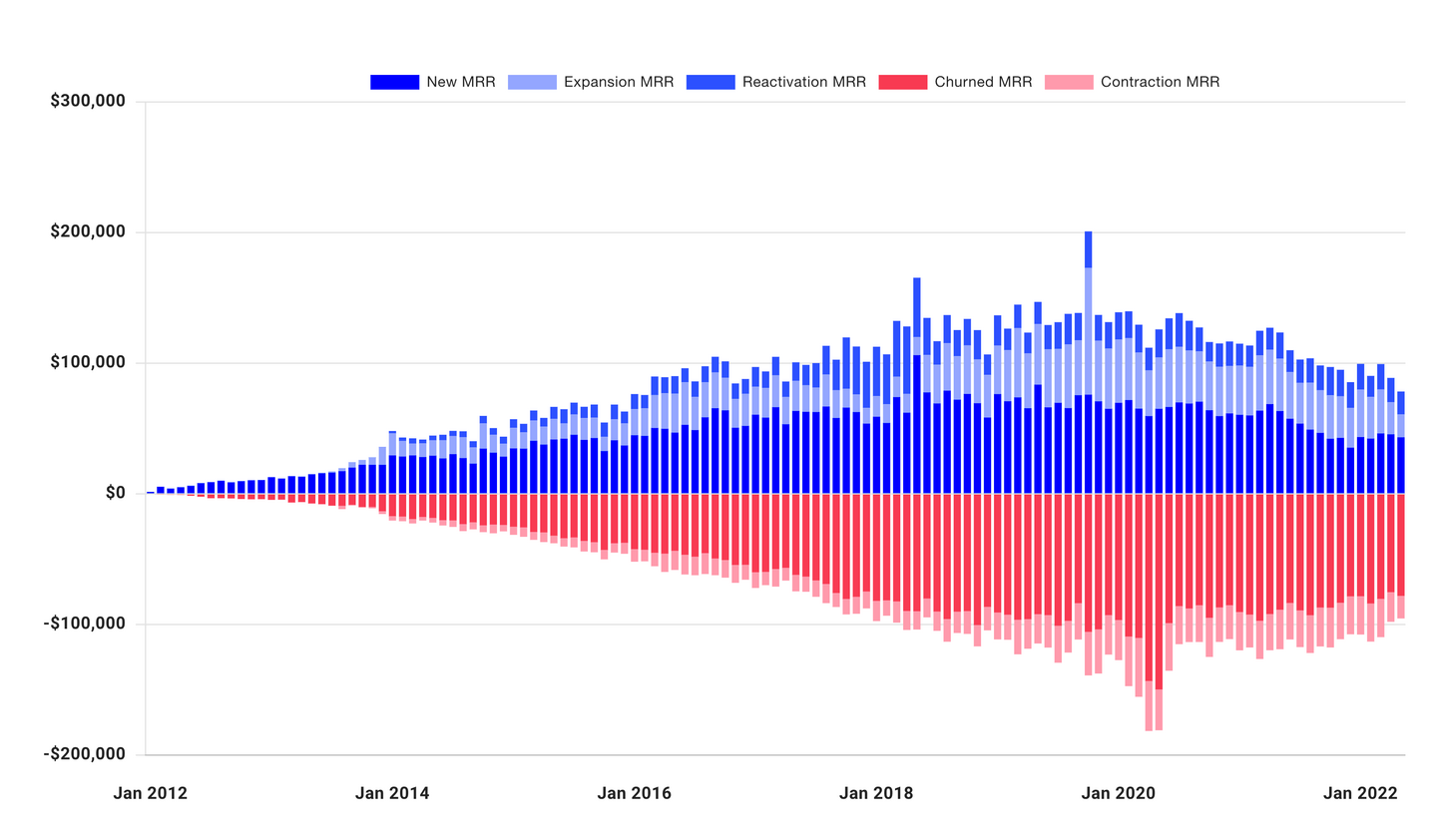

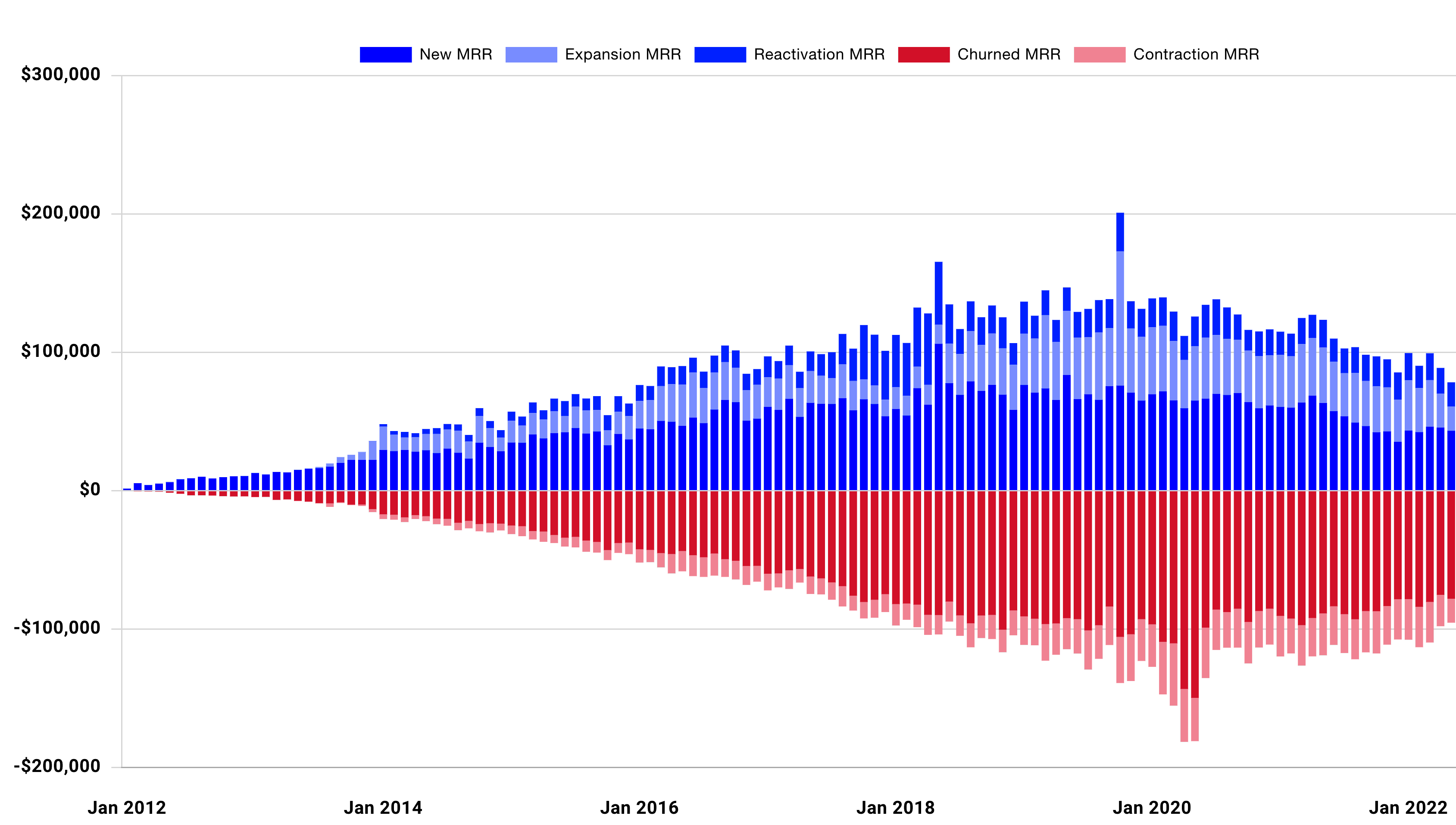

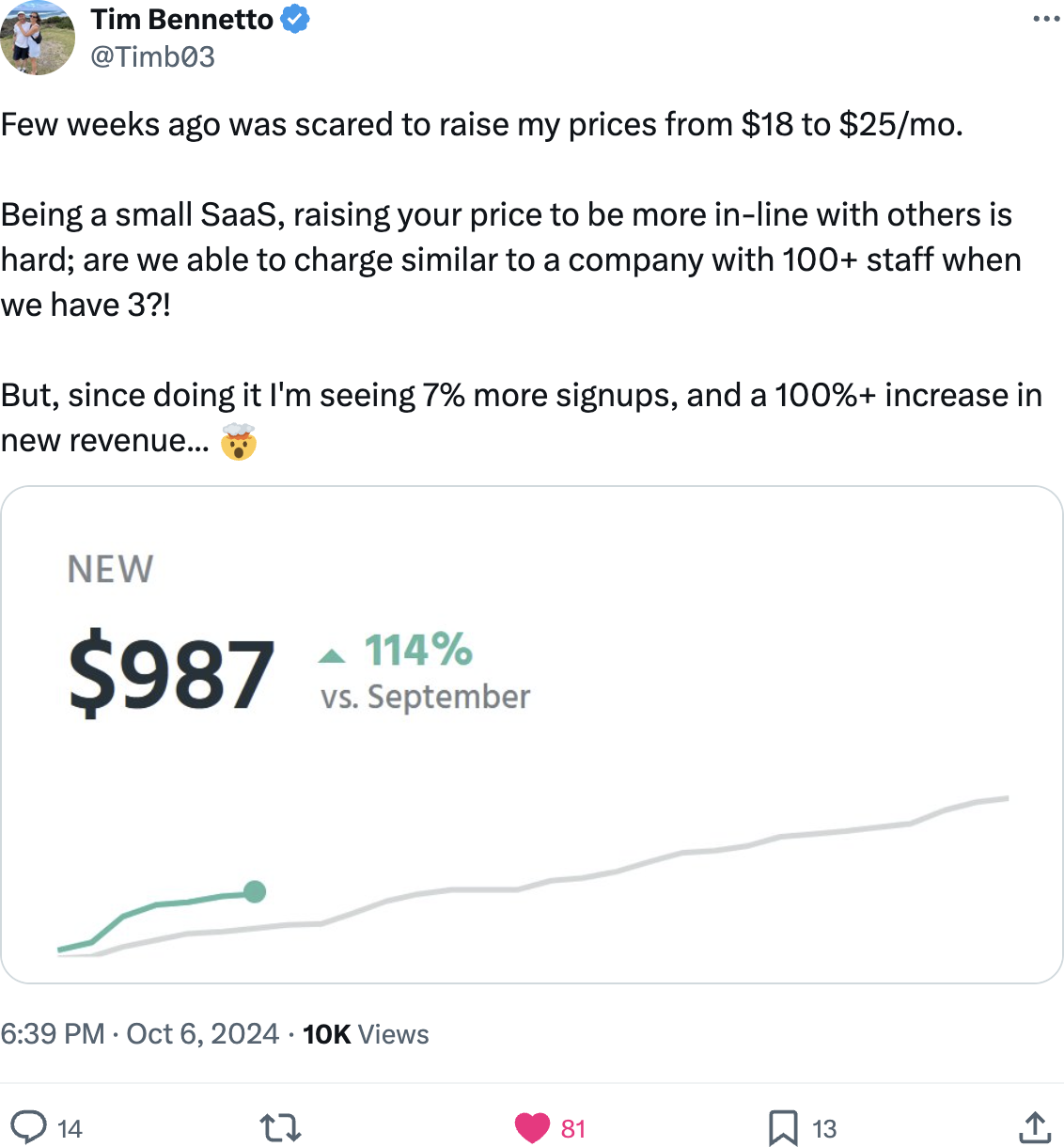

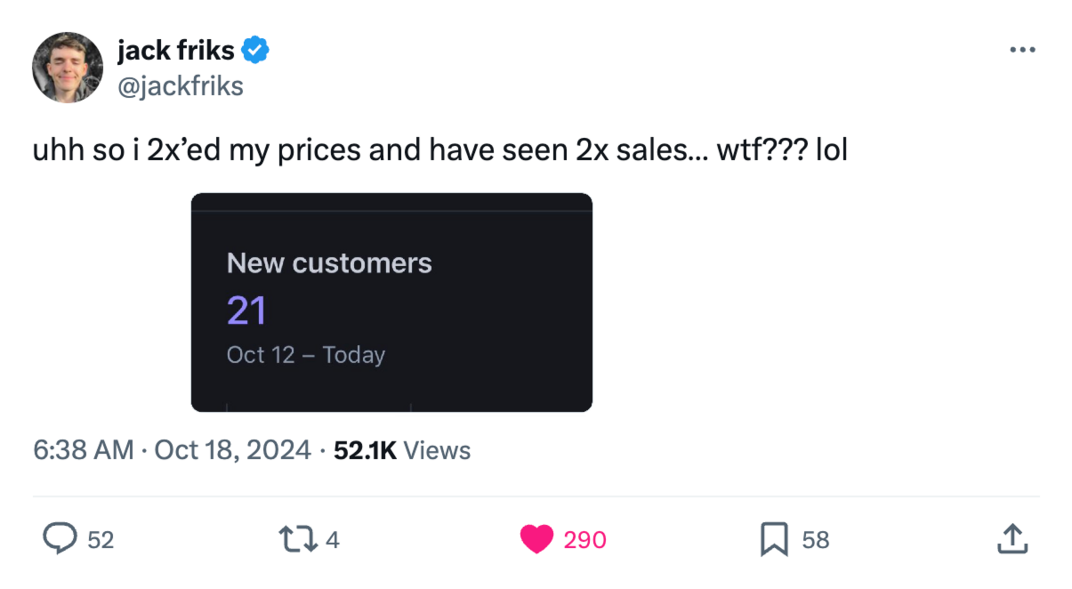

Q2: Is your pricing correct?

The answer is almost always: No.

Patrick Campbell explains why in Figure 6.

Figure 6

But also, the problem is almost always: It’s really hard to know.

Even small changes in pricing can instantaneously increase revenue without changing how many people sign up every day, or how many people cancel every month. (Which means it dramatically increases profitability.)

Two examples from small companies (Figure 7) (Figure 8).

Figure 7

Figure 8

The obvious action is: Experiment. There are more systematic ways, but they’re difficult to execute, and in my experience, even with expert assistance, half the time you get it wrong.

Indeed, price increases don’t always work. When customers don’t have more money, or demand isn’t strong, or competition is strong, or you’ve built your reputation on having the lowest prices, it won’t work. And if you increase too much, it’s not the same business anymore.

Yes, pricing is art as much as science. It’s also one of the largest and most immediate levers you have.

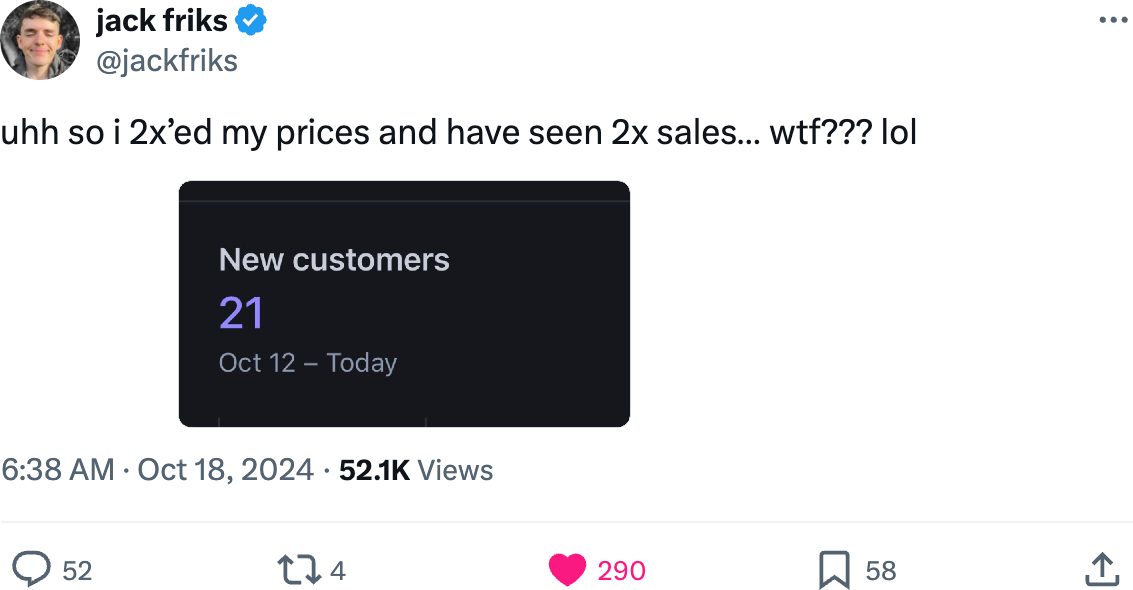

Q3: Are existing customers growing?

The next step is to examine “net churn”, which considers both cancellations and internal growth—how much revenue you’re generating from existing customers through increased usage, or tier-upgrades, or additional add-ons.

Many small companies overlook the importance of internal growth, because when you’re small, there’s little existing customer base to grow, so it’s smarter to focus on getting more customers instead. But that form of growth inevitably slows as the company grows, so your focus has to change as the company changes.

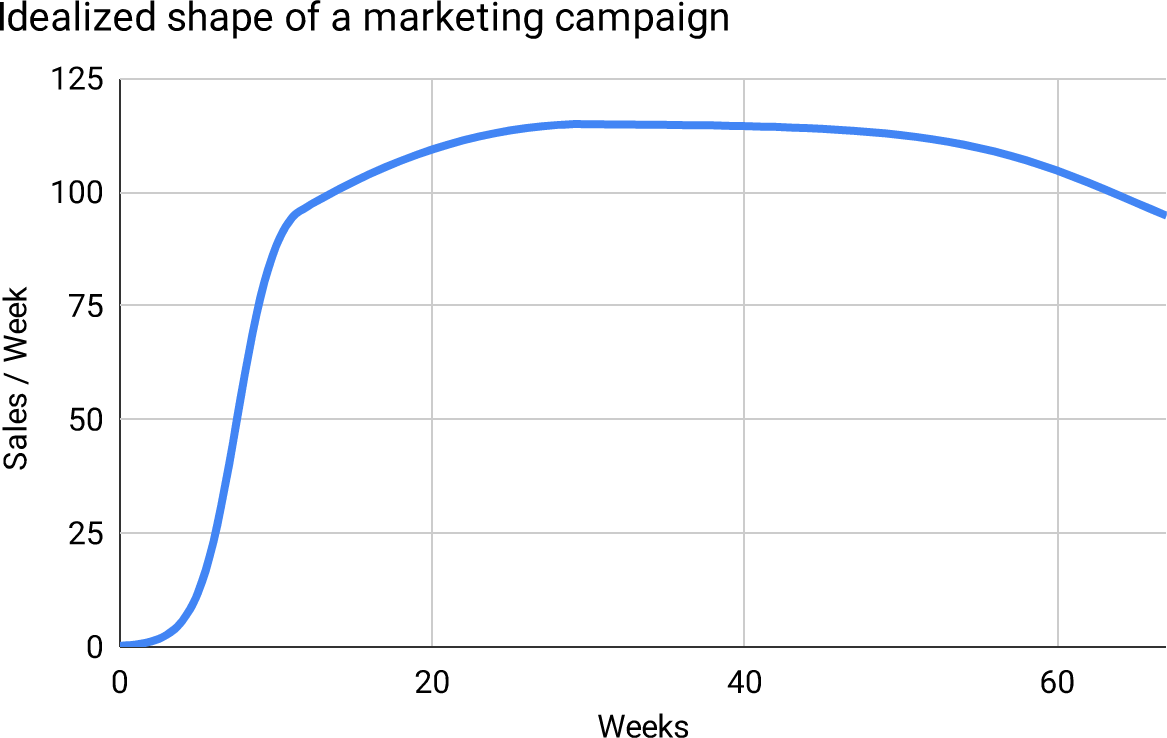

The mathematical problem is that new-customer-acquisition grows with marketing, which is not exponential, but logo-cancellation is a percentage of your size, which is exponential. As a result, plotting “new-versus-cancel” generally looks like this:

Figure 9: A model with $1000/mo of new revenue and 5%/mo cancellation. Growth tapers off as cancellations outstrip new customers.

While new-customer-acquisition will never scale with the size of your company, a different growth vector does scale that way: Upgrades from existing customers. If 5% of customers upgrade per month, that counteracts 5% cancelling per month.

The modern metric for this is NRR (Net Revenue Retention). It is the annual revenue percentage change due to cancellations and downgrades (negative) and upgrades (positive). So e.g. with 30%/year cancellations (equivalent to 3%/mo), 10%/year downgrades, and 50%/year upgrades, all measured in ARR, we compute:

NRR = 100% - 30% - 10% + 50% = 110%

Your goal is NRR > 100%. This means you’re not just compensating for churn, but growing even if you never added another new customer.

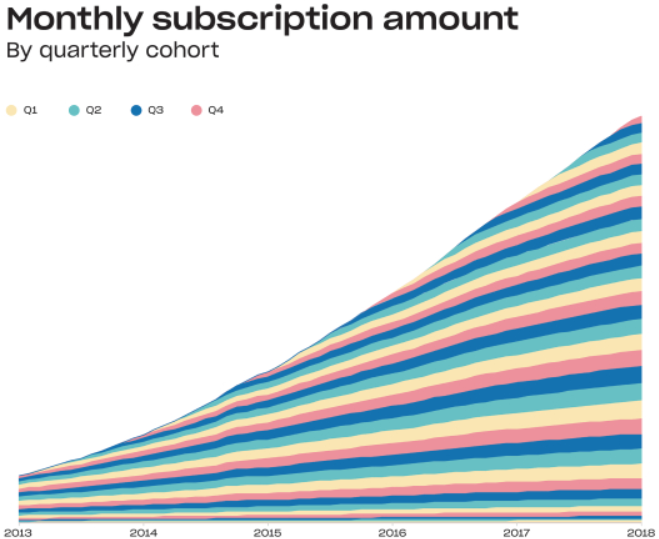

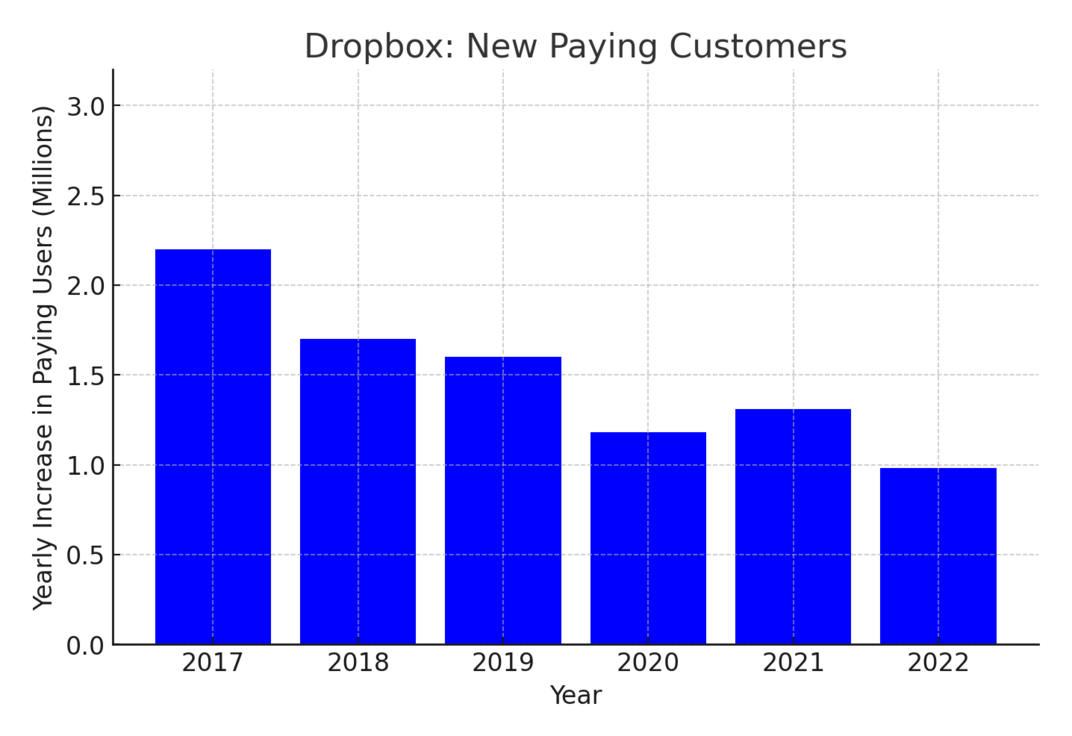

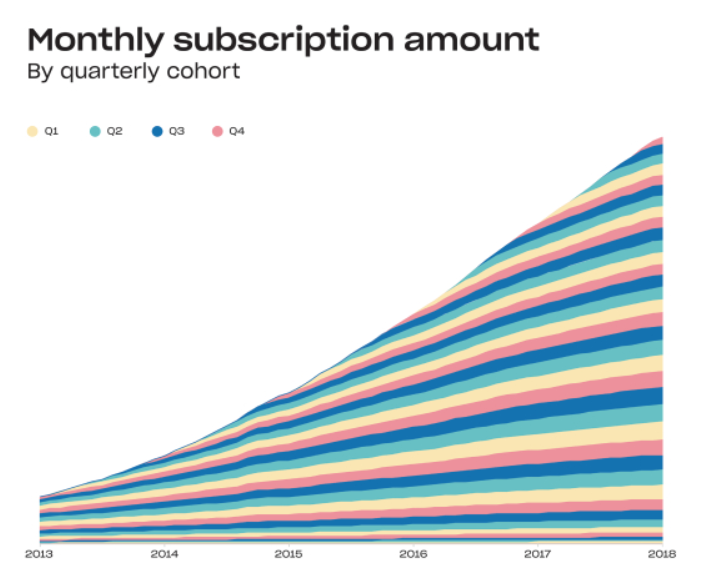

For many at-scale companies, NRR growth is greater than new-customer growth (Fastly, for example). Dropbox saw significant growth by introducing tiered pricing and premium features that encouraged existing users to upgrade. This boosted their NRR and propelled their growth (Figure 10), even when new customer acquisition slowed (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Dropbox customer cohorts grow faster from internal upgrades than they shrink from cancellation.

Figure 11: That’s why Dropbox revenue continues to accelerate, even though the rate of adding new paying customers continues to decelerate.

Often the problem is that you don’t have a pricing mechanism that encourages upgrades. The classic “best” way for a SaaS companies is to price along two dimensions:

- Usage (e.g. number of users, amount of data, tickets/month)

- Functionality (e.g. “tiers” that include more features, integrations, service, compliance)

For example it makes sense for Support Ticket Desk Software to charge more if more reps are using it (usage), or for additional features like AI responses (functionality).

The rule is that customers ought to pay more only when they’re getting more value. Then it’s fair and sensible, being at least Utility, not contrary to Love, and certainly not Coercion (from my WTP framework).

Often price-tiers segment the customer base, both by their budgets and their requirements. Large companies are willing to pay more for integrations and a higher tier of support. But customers don’t often change segment (e.g. rarely does a small business grow so much that it becomes a large enterprise), and therefore this doesn’t help you with upgrades. Therefore, assign features to tiers not only in terms of where a segment might land, but how a customer could become a power-user, growing in terms of functionality rather than changing their segment.

Q4: Are acquisition channels saturated?

With positive NRR, you can turn back to the question of new customers. If the rate of “new customers arriving per month” has stalled—or even sagged—you’ll want to address that.

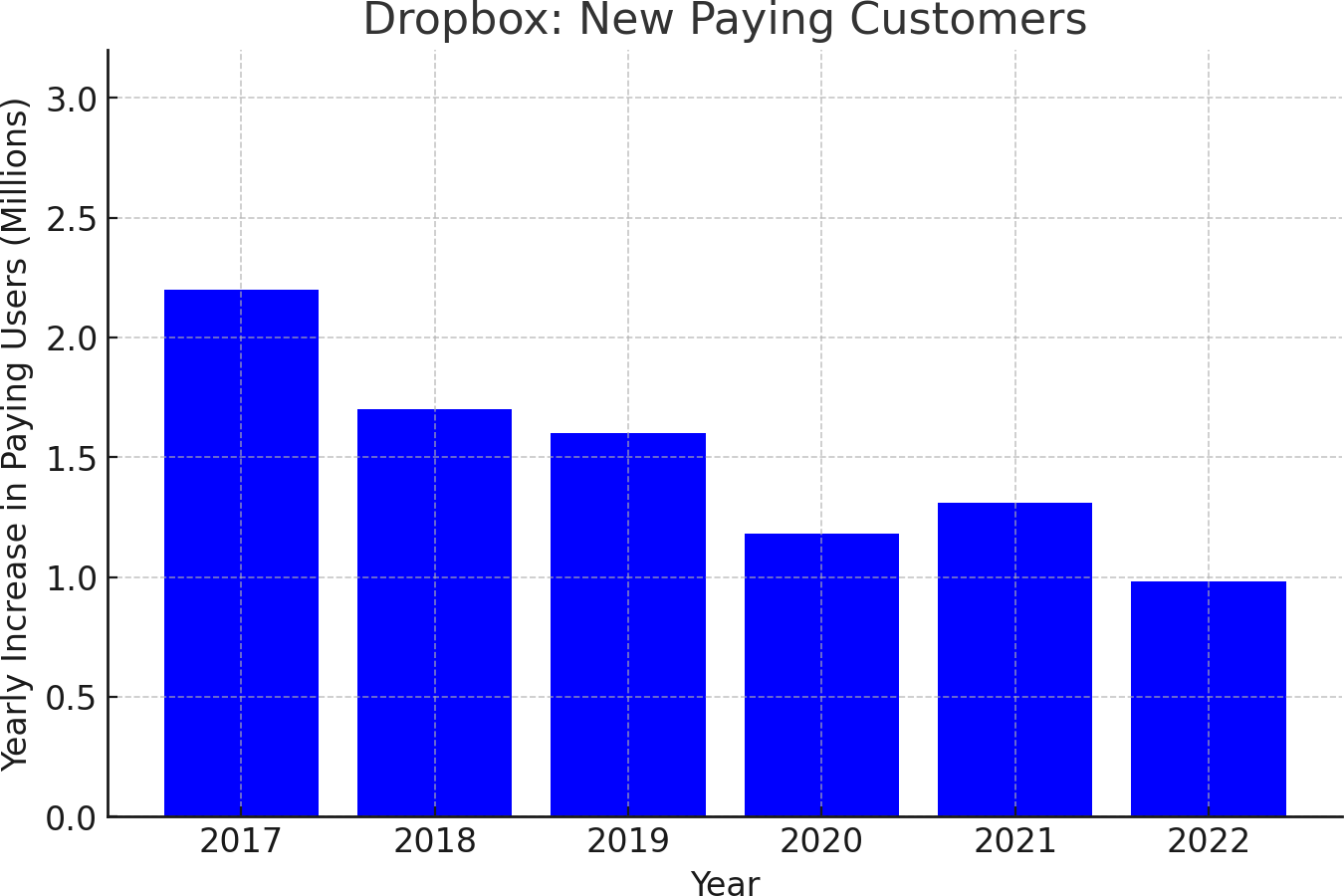

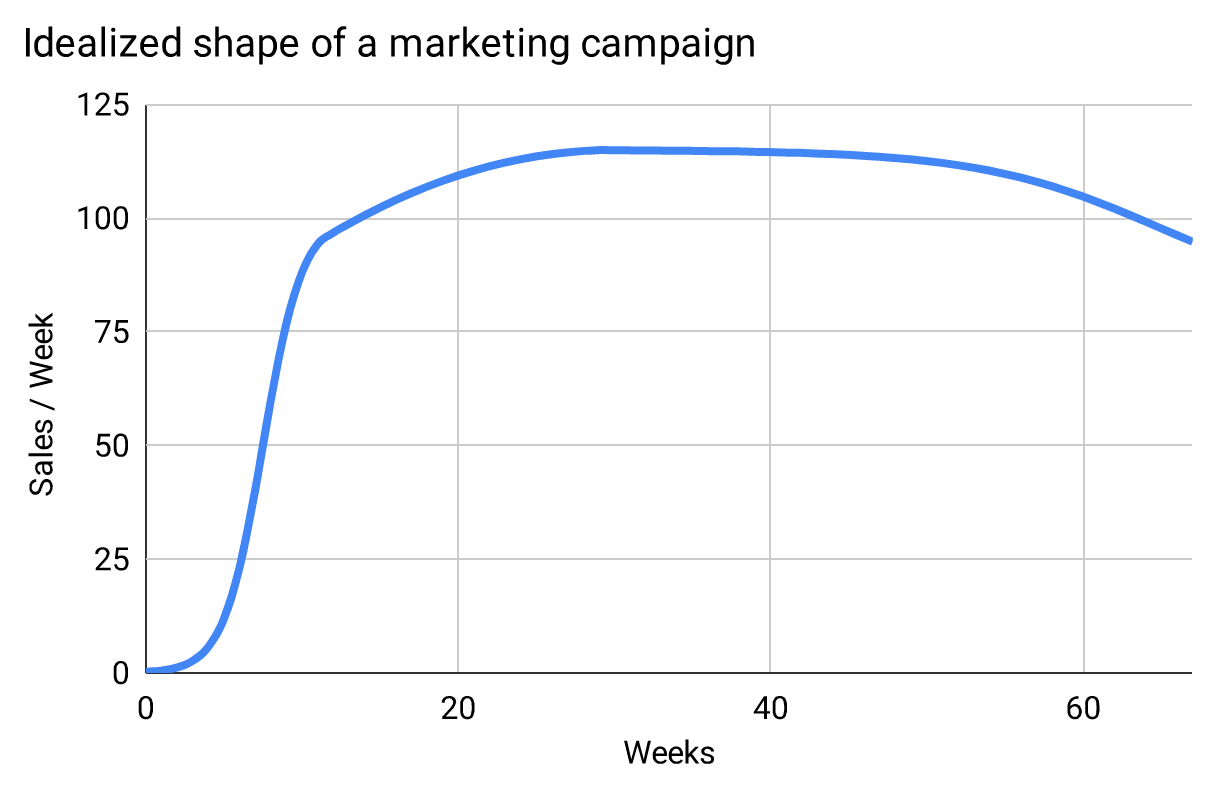

In fact, stalling and sagging is what marketing campaigns naturally do. I have covered this in detail, explained through realistic models and supported by real-world examples, in this article about exponential growth:

Figure 12

The first thing is to find the bottleneck of your conversion funnel, and try to widen it. Use data to determine what’s restricting sales: Not enough new people coming to the website? Traffic quality is too low? Close rates too low? High churn in first three months?

Sometimes you can double growth by transforming the rate-limiting step. Careful though: Often “fixing” one step just sends the problem downstream, where it’s even more expensive to detect and fix. For example: You increase traffic to the website, but it’s low quality, so sales conversations decrease, so not only is growth still stagnant, you’re also wasting more time in useless sales calls. Therefore, try to do the opposite, i.e. if sales conversion rates are poor, of course try to improve sales techniques, but also check whether you could increase lead quality upstream, where it’s cheaper and more scalable.

Another thing you can do is accept a lower ROI. Of course you don’t like over-paying for new customers, but in the long run it might not be a waste of money. This is especially true with positive NRR, because customers will grow over time, which means you can spend more up-front. This can create a cash-flow problem; annual plans can counteract that.

The next obvious thing to do is: Find more channels. If you have only one, this is almost surely the next step. If you’re at scale, and already have multiple, it is worth experimenting to find another, but it’s more likely you have reached total saturation. There are a finite number of positive-ROI marketing channels.

More likely, you’ll need to find a completely new technique for finding—or even creating—new customers.

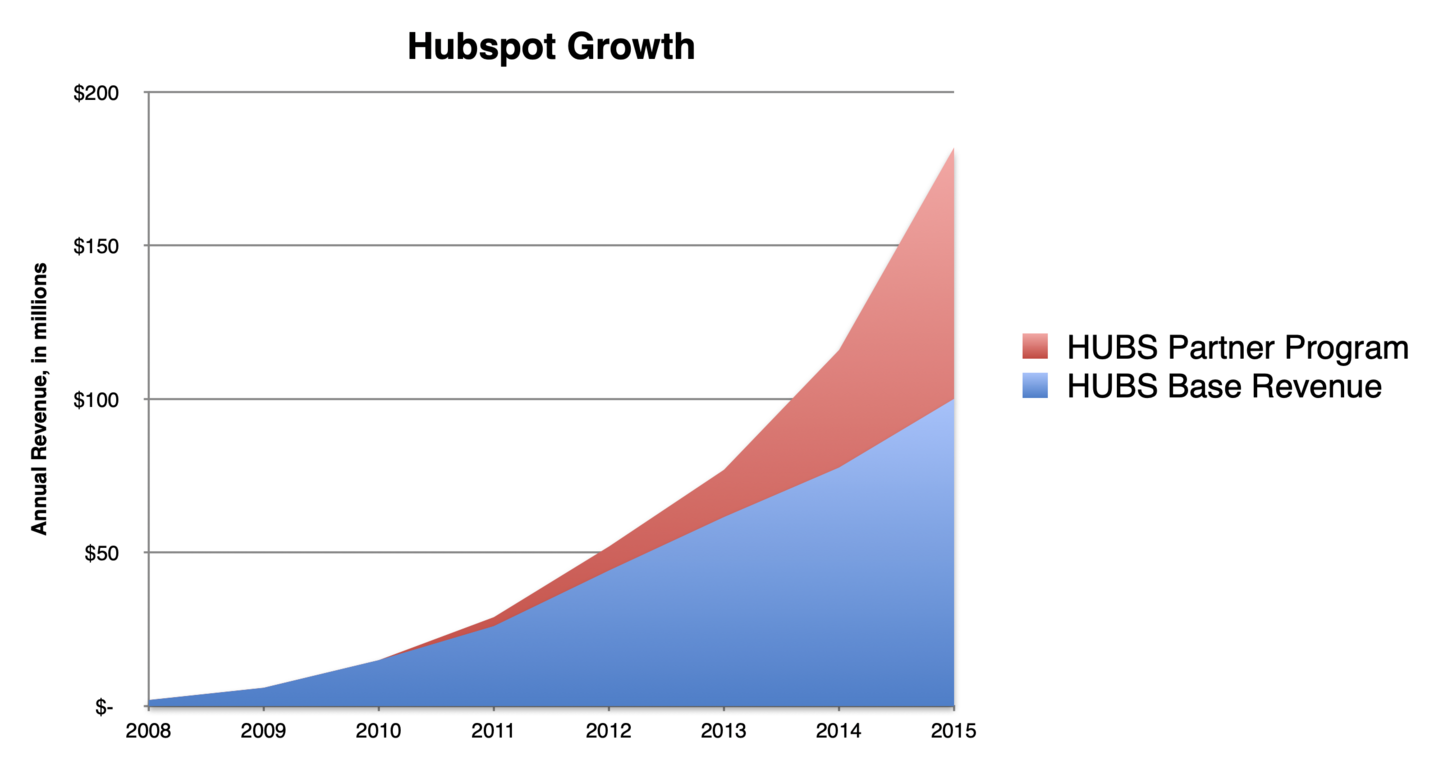

For example, HubSpot hit a growth plateau when selling directly to customers (through multiple channels). The way they solved it was with a dramatically different channel: Reselling through agencies. It took years before that effort was making a material impact on growth rate, but then it became fully half of their total growth:

Figure 13

Quickbooks was similar; they sold their accounting software directly to small businesses through stores (before the internet!), but most of the growth was through selling software to accountants, because the easiest workflow for the accountant was to import data from Quickbooks, which meant the accountants forced their clients to buy Quickbooks.

Constant Contact (email marketing for small businesses) hit a growth plateau, and it was expensive to advertise to the non-aggregated audience of “small businesses” who would pay only $20/mo. They realized that most small businesses didn’t even know where to start with email marketing; that meant there might be 10x the market if they could educate the business owners. Since those owners weren’t internet-savvy, Constant Contact came to them—hosting myriad in-person training sessions, a few dozen business owners at a time, across dozens of cities in America. It worked; as expensive and non-scalable as that may sound, it broke through their stalled acquisition.

Q5: Is your target market saturated?

Markets are not infinite, especially when you consider the small subset of the market for which your product is “perfect,” i.e. the one housing your ICP (Ideal Customer Profile). Perhaps you are already reaching everyone who you can reach.

Now it’s time to expand the market. But in which direction? What is most lucrative? What is least risky? What makes sense for your company at this stage, at this time, with this budget?

See this article on expanding into adjacent markets for details on how to identify this and make the decision.

Q6: Do you even need to grow revenue?

“If you’re not growing, you’re dying” as the saying goes.

Your knee-jerk reaction might be: That’s what money-grubbing investors say! It doesn’t apply to me! But, I’ve heard this phrase my whole career, including at bootstrapped companies where the founders hated VCs. The phrase is not necessarily wrong.

Still, it’s not necessarily right. What is right?

You must decide what is important to you. Maybe you want to maximize profit instead (but not at the expense of what’s fair to customers or what you would be proud of doing). Maybe you want to minimize how much time you spend on work that you dislike. There are many more choices; the only wrong choice is to avoid making a clear choice, because then you can’t aim the company at that choice.

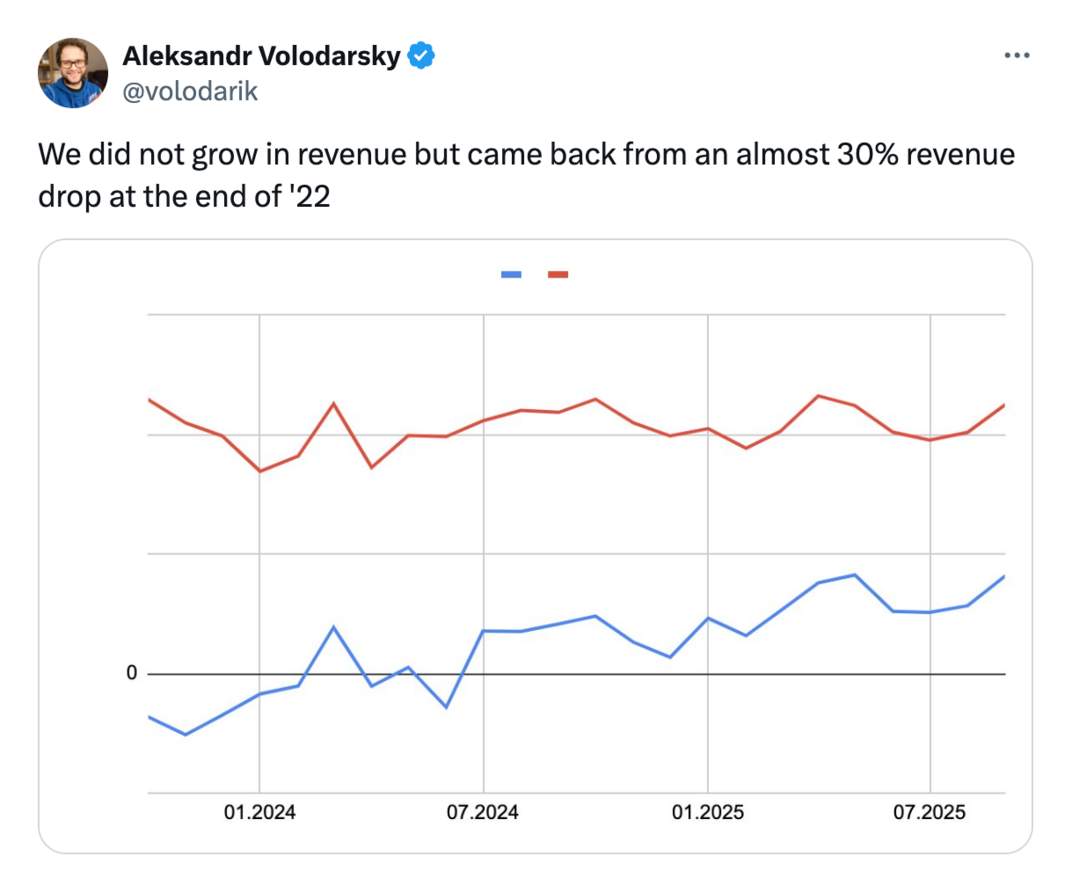

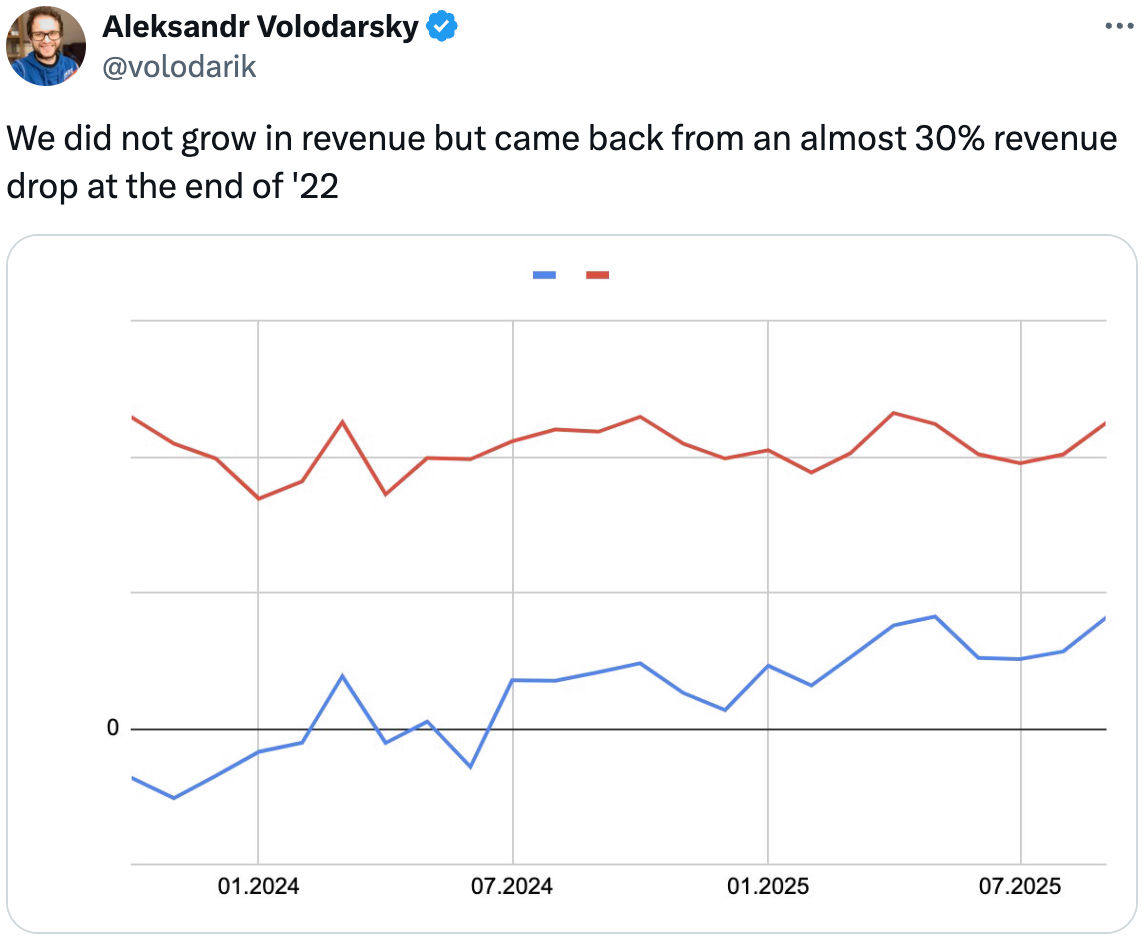

For example, Alexandr Volodarsky hit a revenue plateau with lemon.io, then successfully pivoted to increasing profit instead:

Figure 14: Revenue (red) remained flat while profit (blue) grew.

Or, it might be time to sell. Perhaps someone else has the energy and motivation to take it to the next stage. Maybe you simply want to do something else, now that you’re older and have significantly more money in the bank and confidence in your head. Maybe selling now maximizes money in your bank account, because if you wait another three years, revenue will continue to sag, and your sale price will be dramatically lower (both because of lower revenue, and much lower revenue-multiple).

No one can make that choice for you. Don’t let others bully you either that you “must” sell or “must not” sell. It’s highly personal. Listen to others, gather differing opinions, but treat them as “ideas,” not “mandates.” Maybe take a sabbatical and find out whether the prospect of returning to work fills you with excitement or dread. In that case, your “gut-feeling” is correct.

Congratulations on building a fantastic business! Now honestly diagnose what’s holding you back.

Thanks to Josh Ho for feedback on early drafts.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/growth-asymptote/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF