Distinguishing constructive criticism from bad business advice

Franks & Gerrys

Haiku:

With their eyes of ice

high-powered executives

know better than you.

I was starry-eyed when Frank showed up 18 months after the birth of my company, Smart Bear. Picture it: Frank was a silver-haired ex-VP-of-Sales for a big, successful company. An IPO had made him comfortably wealthy, and now he wanted to hook up with a promising new startup. With his résumé and enough money that he never had to work again, he could be choosy.

And he chose little ol’ me!

And boy did I (think I) needed him. “I’m just a software developer, I don’t know anything about sales” I explained to Gerry, who had already unknowingly cemented himself as my mentor. “I’m just a lowly engineer, ignorant of the mystical voodoo of six-figure purchase orders. I don’t even play golf! Frank has been there.”

Gerry tried to explain. “There’s no magic to it. I’ve sold companies for $100 million without stepping foot on a golf course. You have a good product, you have some customers, why do you think you need to change? What would happen if you just kept going?”

Sage advice! So of course I didn’t listen.

Frank and I headed down the road to partnership. Frank had lots of ideas that “we have to implement, otherwise no big company will give us money.” For example, we had to change our name. “Smart Bear” sounded to Frank like a dorky one-man shareware site. (Ahem…) We needed something stoic and corporate. His suggestion was “Software Test and Deployment Systems, Inc,” or STDS1 for short. “Big companies like acronyms,” he explained, as if Big Company were an entity capable of having an opinion.

1 It apparently didn’t occur to him that this acronym is already taken. At least we could have leveraged viral marketing! (I could have said “used” but Frank would have said “leveraged”.)

There was more: We needed patents (“to keep competitors at bay”), we needed a sales team (“software doesn’t sell itself”), and we needed to lighten up (“I like to knock off early on Fridays”). In fact, very little of what I was doing, was right.

Fortunately Gerry finally punched through Frank’s dazzling fog. “Let me get this straight,” he rightly admonished me for the fourth time, “this guy wants 50% of the company, he wants a salary while you get none, he’s going to work 35 hours a week while you work weekends, he’s not investing money into the company, and his big idea about how to get more customers is to change your name to venereal disease? Does this sound like a 50/50 partner? Or even someone you want involved at all?”

Gerry’s criticism of Frank was harsh—as harsh as Frank’s criticism of me—but Gerry was right and luckily I (finally!) heeded him.

Two weeks later I landed a $50,000 deal with a Big Company. (It was Intuit.) A few years later we were doing millions in revenue with Big Companies, still called Smart Bear, still no patents, still no sales guys. Who knew? (Gerry knew.)2

2 Editor’s Note: I later sold Smart Bear, and now it’s worth over $2,000,000,000. And it’s still called Smart Bear.

You have to understand though, saying no to Frank was hard. He had the expertise; I didn’t. I was convinced that he was right and I was wrong. If it wasn’t for Gerry’s guidance, I would have gone through with it.

So how do you separate the good counsel from the bad—the Gerrys from the Franks? Both sounded like practical advice and criticism, both were experienced, both were strong-willed, and both truly believed in what he was saying.

Dieting

The answer can be found in the brutal world of dieting.

One thing we’ve learned from the diet crazes since the 1980s is that every single thing has been alternately touted as healthy or poison. No-fat, carb-heavy. Scratch that, no-carb and fat doesn’t matter. Scratch that, it’s only about low-cal. Scratch that, whole-30 and don’t track calories. Scratch that, fast for sixteen hours a day and do anything for the other eight.

Ask any person and they’re equally variable: Which thing worked for them, or didn’t, or worked for a while but it wasn’t sustainable.

So there is no objective answer to the question: What is the best diet?

The only question is: What works for me?

Start-up advice is the same. For every example that incontrovertibly proves “X is right,” there’s another equally compelling story of success where the mantra was “X is wrong.” The company that won because prices were low and the company that won because prices were high. The founder who built the company on top of a thriving Twitter following with no advertising and the company where the founder ran ads and isn’t on social media at all. The company that started because “I scratched my own itch” and the company that started because “I researched and located an underserved niche in the market.” The company where the founder won because she was an expert in that field and the company where the founder won because she adopted a new perspective in that field.

So how do we answer the question: Which advice is right for me?

In diets, half the answer is physiological—how your body reacts. The analog in startups is: What is right for this company, in this market, with these competitors, with these customers, at this price-point, with this business model, with this team, with our strengths, with our goals, with our financing, with our culture. Usually the answer is different from what made sense for Steve Jobs or Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg or Jason Fried or Pieter Levels, even though those are the stories we constantly hear. Indeed, all of those are outliers even among their contemporaries; no one should attempt to follow their unique paths.

In diets, the other half of the answer is sustainability—can you keep doing this for a long time? Diets work only with a lifestyle change, not when it takes fresh willpower every single day. It’s fine to say “social media is the key to your marketing success”, but if you think Twitter is insipid and Facebook is unserious and Instagram is fake, will you really be successful if you force yourself to post there? Or should you follow the path of most companies, whose marketing is not primarily powered by social media? It’s fine to say user interface design is critical, but thousands of successful companies have crappy design, so if you’re not a designer and don’t care to invest in one, you should be asking what makes companies successful despite poor design.

How do you determine those personal dimensions (“Who am I?”) or the corporate ones (the list above)? This takes real work; this article explains my system for finding both.

Finding your truth

Beyond the tools in that article, the following have helped me discern the Franks from the Gerrys:

- Insight, or an excuse?

- Ask yourself: Do I like this advice because it’s justifying some behavior that deep down I know is actually wrong? Or do I like it because it’s clearly articulating a ground truth? For example, if you inherently dislike social media, of course you can find advice telling you how social media isn’t important, but did you enjoy that because it feels correct deep down that social media is a farce, or did you enjoy that because it’s an excuse to avoid the truth that social media is critical in your chosen market. If you proactively ask yourself—even though these are feelings—the answer will often be clear.

- Context

- Advice is valid only within a certain context, yet the boundary of that context is often unknown to both advisor and advisee. The rule of thumb is: Advisors give advice to themselves. Meaning: Within the boundaries of their personal goals, their world-view, the markets and products and customers and competitors that they’ve experienced, they can probably provide some great advice. Outside of that, who knows? So ask yourself: Does the person behind the advice match me on all those dimensions? If so, this could be relevant wisdom, even if the message is hard to hear. If not, you can either ignore it completely (“Focus!”) or sift it through a substantial mental filter.

- Questions, not answers

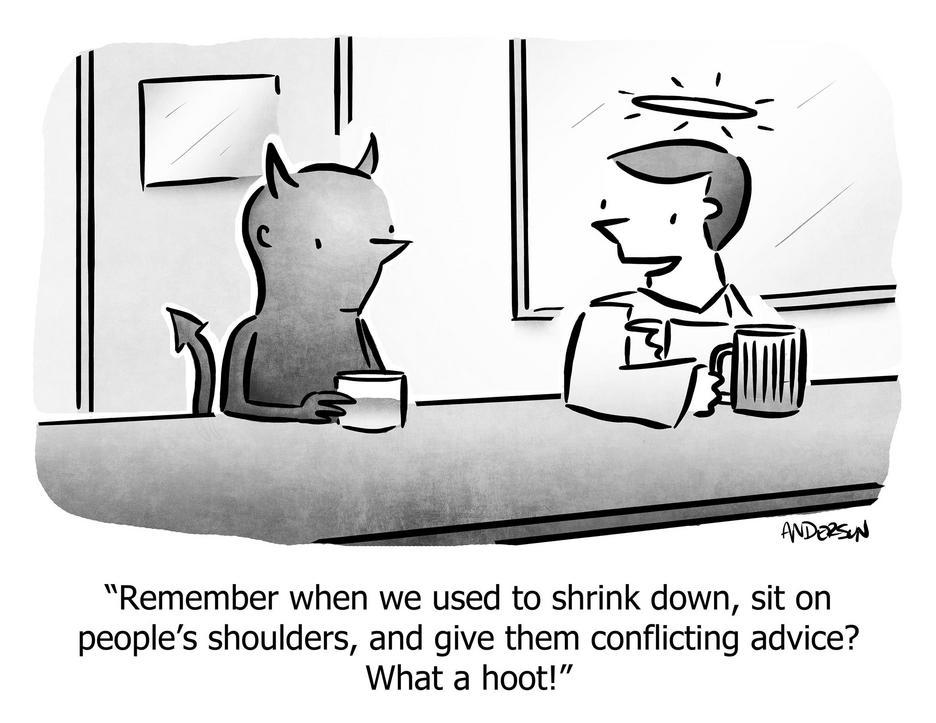

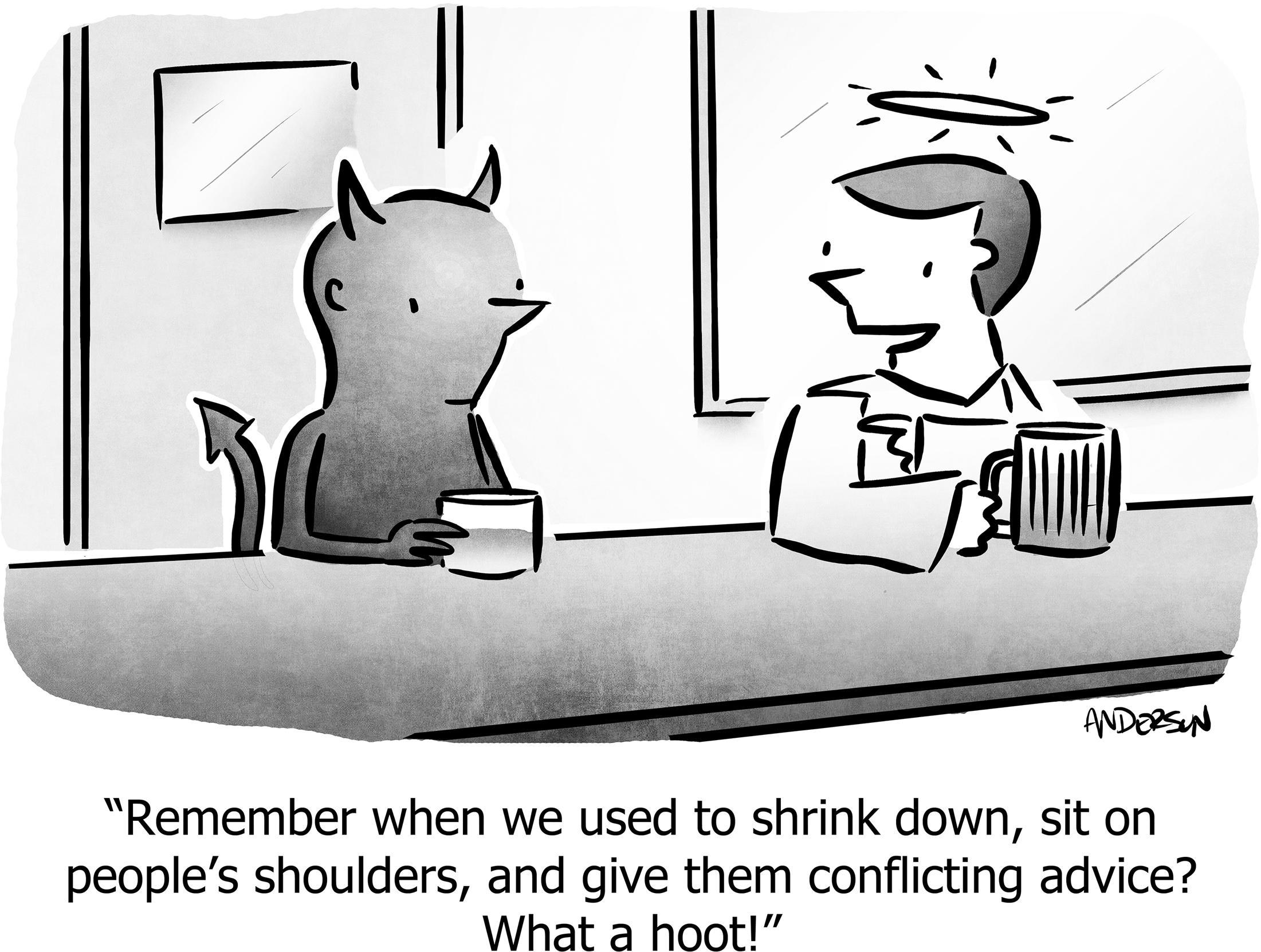

- The best advice doesn’t come as a barrage of commands but rather from a series of questions, asked by a devil’s advocate. Rarely will an advisor know more than you do about your domain of expertise but that doesn’t mean an outside voice is useless. Pointed questions force you to defend your choices. A healthy debate challenges your assumptions without implying they’re false. New ideas are batted around as a brainstorm rather than handed down as gospel. Even Roger Federer has a coach, not because the coach is “better at tennis” or giving him commands, but because he is a mirror and a provocateur. In my case, Frank presented his view as a series of statements; axioms, even. Gerry couched his perspective as pointed questions that required either rebuttal or agreement. In fact, playing devil’s advocate is a great exercise to do periodically. Find an intelligent foe, take her to lunch, and follow Scott Berkun’s advice about Rude Q&A.

- Some learning starts with revulsion

- Pay attention to advice where you have an immediate, automatic revulsion. Often this feeling is correct, because you’re want advice that matches your context, and revulsion indicates a mismatch. But, if you are wrong about something, this is what it feels like to discover that. This is an opportunity; don’t waste it!

- “This is how it’s done”

- “This is how it’s done” is almost never a good reason. If the sole basis for the advice is “tradition,” it’s just momentum and you might be right to buck the trend. Example: Smart Bear posts its prices on the internet rather than negotiating. Enterprise software sales are rarely done that way, but posting your price is honest and makes business sense, so we do it anyway. That said, many founders act like tradition is there to be contradicted. Much of tradition is hard-won wisdom. So, traditional answers carry neither positive nor negative baggage; they should be investigated like all other ideas.

- Constructive vs critical

- It’s easy to cut down ideas; it’s hard to create and execute them. Give me any idea and I can find someone who thinks it’s dumb. So what? “Constructive” criticism means constructing, not just blasting. Look for advice with a clear method for implementation and a clear way to know whether it is working, especially since an idea worked for one company might not work for another.

- Put your metrics where your mouth is

- Does the advisor volunteer a clear way to measure the success of her new idea? If so, the idea is self-evaluating, and you can change if it happens to not work for you. This is the guiding principle behind our marketing efforts at Smart Bear.

- Develop relationships

- Actively develop a network of trusted advisors. These could be local entrepreneurs, on-line forums, even bloggers you like. Everyone needs a Gerry or two. Advisors won’t always agree with each other of course, but nothing beats running ideas past people you respect and who truly have your interests at heart, even if their advice ends up being wrong.

- Gut feel

- Your gut often knows the answer. I know you don’t want the answer to be “feelings,” but sometimes feelings are wiser than thoughts. In a world where both “X” and “Not-X” are convincingly peddled as The One True Way, you might need something outside of pure logic to resolve the path. If you find yourself vigorously agreeing with some new idea, that might be all the evidence you need.

Besides, no one knows what’s right, not even me.

Seek advice that helps you become a better version of yourself, not advice that aims to change who you are.

Being yourself is the only thing you’re going to be good at, anyway, which is what will give you the leverage you need to win.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/bad-advice/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF