Ignoring the Wisdom of Crowds

Let’s start with some fascinating, unassailable facts. Then we’ll assail them.

Jellybeans

In 2007 Michael Mauboussin presented a big jar of jelly beans to his seventy-three Columbia Business School students. How many beans did they think it contained?

Guesses ranged from 250 to 4,100; the actual number was 1,116. The average error was 700—a massive 62%—demonstrating that the students were awful estimators.

Now here comes the weird part. Even with all these wildly incorrect guesses, the average of the guesses was 1,151—just 3% off the mark. The group’s average was closer than almost one person’s guess—only 2 of the 73 students guessed better.

So although individually everyone was woefully inaccurate, collectively the group was incredibly accurate.

Was this a fluke? Hardly. The experiment was made famous in 1987 by Jack Treynor. In his case it was 850 jelly beans and 56 students. The group average was only 2.5% off the correct number; only one student guessed better. The study has been repeated many times with similar results.

This eerie effect goes beyond jelly beans; it’s also a big help when you’re trying to make money on TV.

The best multiple-choice test ever

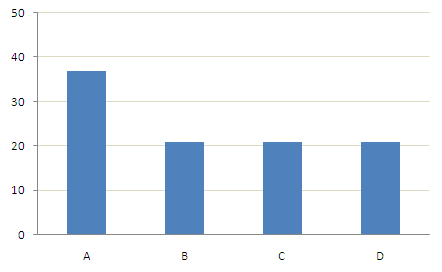

A contestant on the game show Who Wants to be a Millionaire wins a million dollars if she correctly answers fifteen consecutive multiple-choice questions. If she’s stumped along the way she has three “life-lines”: (1) eliminate two of the four choices, (2) telephone a friend, or (3) poll the audience. The jelly bean experiments imply that this third choice might be pretty good. Is there as much wisdom in the crowd for pop culture and science as there is in counting jelly beans? See for yourself:

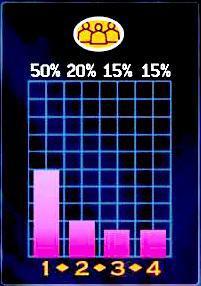

Figure 1

The TV studio audience predicts the correct answer an astonishing 91% of the time. Remember, these are questions from all domains of knowledge, all ranges of difficulty, polling a group of people whose only qualification is that they happened spend this weekday afternoon in a TV studio.

To quantify how amazing that is, compare with the accuracy of the “phone a friend” life-line where the contestant gets 30 seconds with a pre-determined person. This accomplice is probably considered to be “the smartest person I know,” plus has access to the web of lies Google and Wikipedia.

The intelligent friend with broadband access to the entirety of human knowledge gets it right only 65% of the time.

Crowd wins again.

Is the rule universal?

There’s seemingly no end to studies like these, all showing that the crowd is smarter than the individual. Is this a universal rule? Should we be leveraging this power more often?

Big companies do use crowd wisdom. You always hear about advertising campaigns being honed by focus groups of “real people.” (I’d like to see the questionnaire that distinguishes “real people” from that elusive other kind of person.)

However, company messaging, product features, advertising layouts, and the other creative aspects of business require innovation, and we know that design-by-committee is the antithesis of innovation. Average products designed for the average consumer is the opposite of innovation, and probably a bad product strategy too.

So what should we do? Can we rely on the wisdom of the collective or should we trust a stroke of inspiration?

Analysis of how “crowd wisdom” works

Let’s take another look at Who Wants to be a Millionaire.

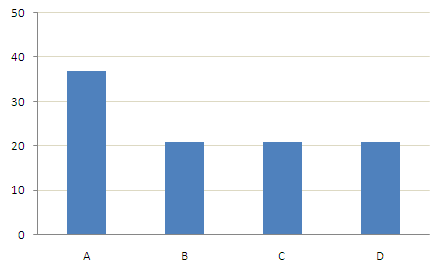

Suppose there are 100 people in the audience and only 16 of them know that A is the correct answer. Of the rest, none knows the answer and they vote randomly. The result of the vote will be: 37, 21, 21, 21:

Figure 2

Oh gee, it’s awfully similar to the earlier graphic of a real audience poll.

(For those of you so inclined, it’s fun to try more complex scenarios, although you’ll find the result is always similar. For instance, what if only 11 know the answer is A, 15 each know that B, C, or D are certainly not the answer (and vote randomly for the other three), and the remaining 44 have no clue and vote randomly. In this scenario, the vote distribution is exactly the same as the simpler example!)

So we have the interesting result that a mere 16% of the voters were able to make choice A the clear winner—nearly double the next closest answer. The reason? The ignorant people vote randomly and their votes cancel out, leaving the few in control of the result.

The crowd vetoes innovation

Now that we understand how crowds can be right, let’s see why this same process doesn’t work for creative endeavors.

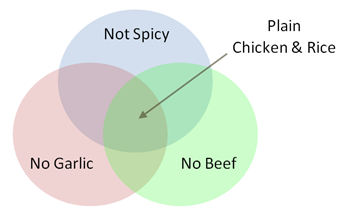

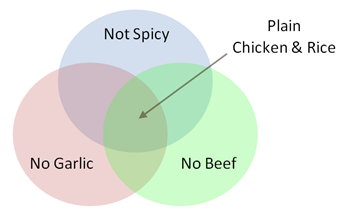

Consider what happens when you’re planning a holiday meal. There’s a range of fantastic things you could cook, but wait: Some people can’t take spicy food, Uncle Bill is allergic to garlic, Aunt Sarah doesn’t eat red meat, Timmy doesn’t eat anything green, ….

Eventually you realize there’s only way to please everyone: Cook something bland, mild, and safe, like chicken and rice (Figure 3). But does chicken and rice actually please anyone? Not really, it was just what everyone hated the least.

Figure 3

Votes don’t converge on something wonderful. Rather, votes are vetoes.

Of course if you’re a catering company for weddings, chicken and rice might be the way to go! After all, no one goes to weddings for the food, so your primary goal is to piss off as few of the 300 guests as possible. Come to think of it, chicken and rice does seem to be popular at those sorts of functions…

But this isn’t a good strategy for startups. Little companies need a niche—a market space they can completely, unquestionably own, not some gray middle-ground where your attempt to offend no one also means exciting no one.

There is “wisdom in the crowd” when there is an objectively-correct answer, and when the errors cancel out, like when estimating jelly beans or answering pop culture questions.

In creative work, votes eliminate the interesting edges, because votes result in subtracting rather than adding, leaving only the boring residue that no one hated enough to vote off the island.

That’s not how great products are made.

Further Reading

- The Wisdom of Crowds by James Surowiecki, with more stories and implications for Wall Street, and his (more expert than my) analysis on the five elements required to form a wise crowd.

- The Difference by Scott Page, explaining how diversity makes a group smarter. The inspiration for my Who Wants to be a Millionaire example.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/wisdom-of-crowds/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF