The Lindy Effect on startup potential

The first 90% of the code accounts for the first 90% of the development time. The remaining 10% of the code accounts for the other 90% of the time.

—Tom Cargill, Bell Labs

However long it has taken us to get a project “close to done,” it will probably take that much time again to really be done. It’s funny because it’s true.

Why is it true? Here’s a novel way to frame it: When you’re exploring something new, where the terminus is unknown, you never know how far along the path you are. On average, however, you’re halfway there. This is due to the very definition of “average”—you’ll spend 50% your time before the half-way point, and 50% after.

This general rule is called the Lindy Effect: For certain non-perishable things (like technology, companies, books, and ideas), the expected lifespan is twice its current age.

Rewriting the same rule with different language allows us to apply this rule to startup growth:

However large you’ve gotten, you can probably double it.

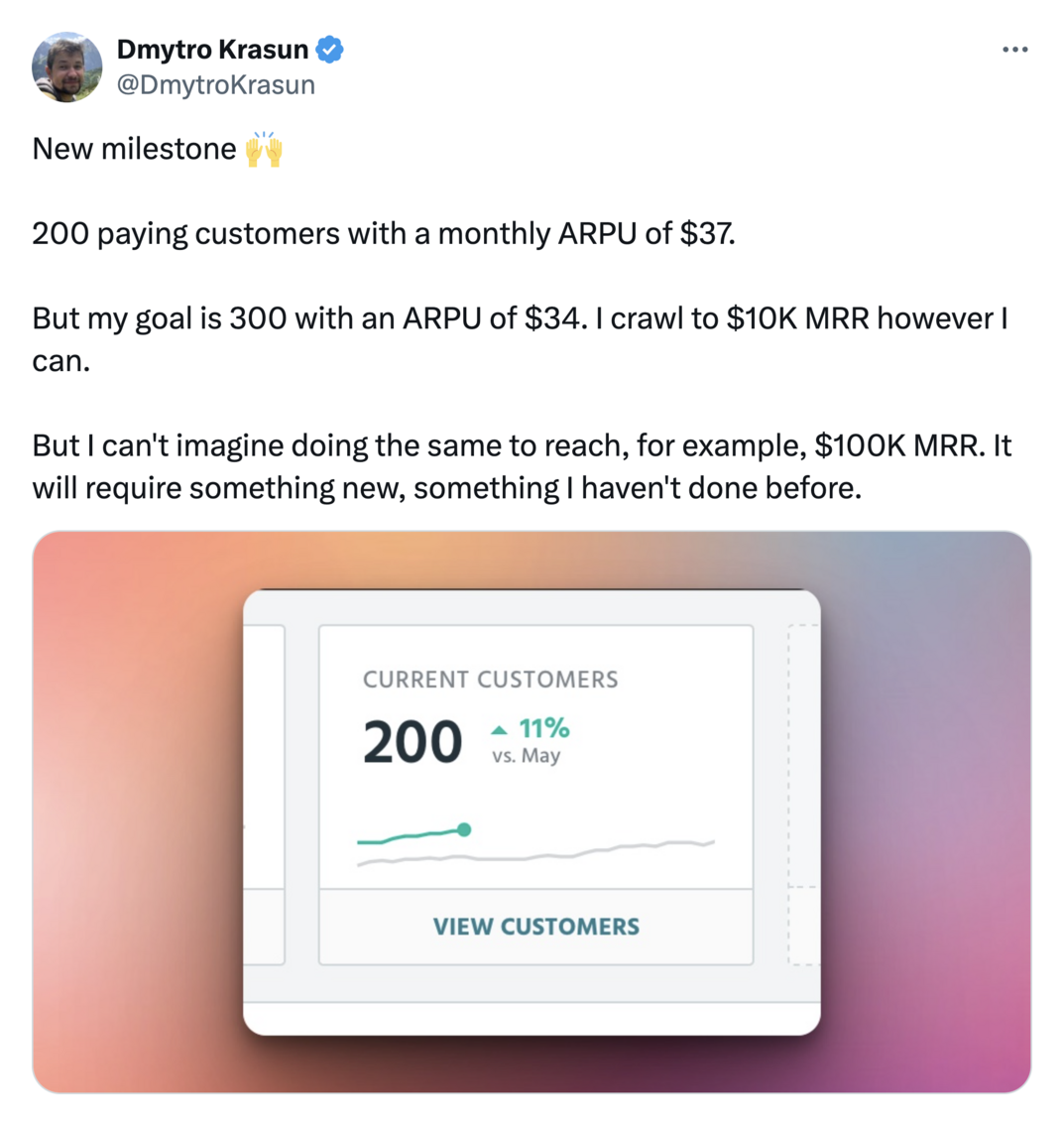

If you’ve gotten 10 customers you can probably get another 10 in a similar way. Will you ever get 2000? I hope so, but most companies that do get 10 never get 2000. Putting it another way, doubling the size of the company always sounds plausible, because you’ve done it once, so you can probably do it again, even faster this time. But 10x or 100x is not obvious at all.

One way to understand why 2x is plausible but 20x requires innovation, is to observe that the actions that got you your first 10 customers are probably not sufficient for generating 100, even though they’re probably sufficient for getting another 10. You might have scratched and clawed inside your social network to get the first 10, but that doesn’t scale to 100, and just because you were successful at convincing customers one-at-a-time to convert through hour-long Zoom calls doesn’t mean you can convert 100 no-sales-touch customers via Google ads.

Or you might have gotten to 1000 customers through one marketing channel. Although surely that same channel can produce another 1000, it’s unlikely that there is 10x the inventory inside that one channel to get you to 10,000 customers. Thus you’ll need to make other channels work, which is not easy to accomplish, as anyone who’s gone through that challenge can attest. In fact, to achieve 10x you’ll probably need multiple new channels. Yikes! Possible? Sure. Likely? No, or at least, not with the confidence you have in 2x.

So the “startup growth” version of this rule is:

You can probably double your size by doing what you’re already doing, but 10x will require innovation.

Figure 1 shows an example.

Figure 1

Or, instead of innovation, time and luck. Specifically, waiting a long time for the existing mechanism to keep working, and lucky that nothing stops that slow but predictable growth: the channel doesn’t saturate and get worse, new competitors don’t arise, market conditions don’t make the product less desirable, the economy doesn’t slow, and so on. Again, possible, but in the fast-moving world of tech, unlikely.

Indeed, at some point 10x is strictly impossible. At the high end, you hit market size limits (Facebook has 2B users; there aren’t 20B humans) or run out of marketing channels for acquisition (GoDaddy’s customer growth rate is 13%/yr since 2009; at that rate it will take 18 years for them to 10x, assuming market size and conditions would even allow them to sustain that). At the low end, maybe there really isn’t a market, or the market really doesn’t want that product, at least not at a profitable price, so you can squeeze out some early sales but it can’t get substantially bigger.

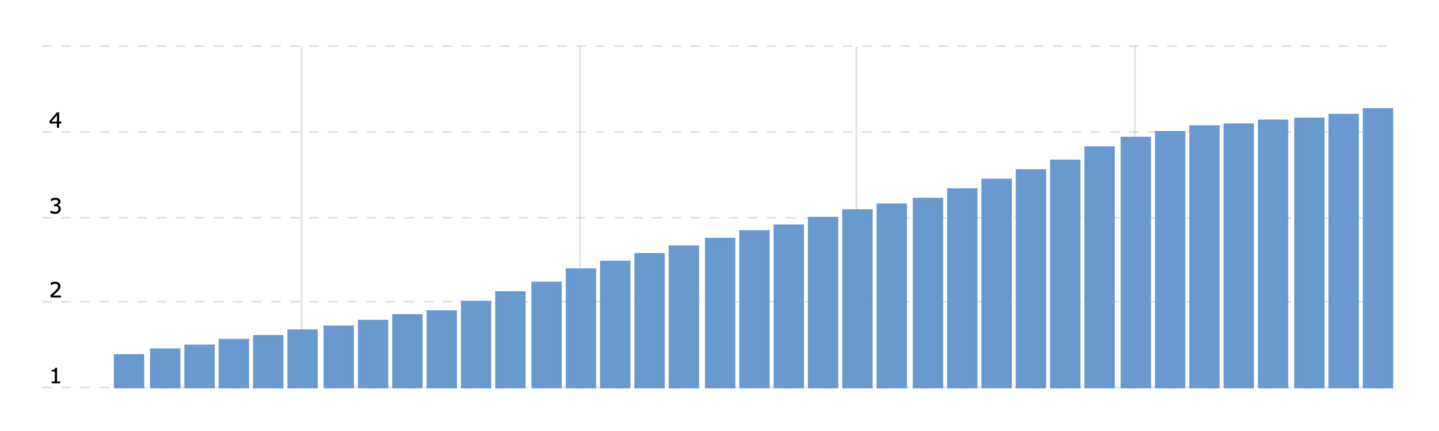

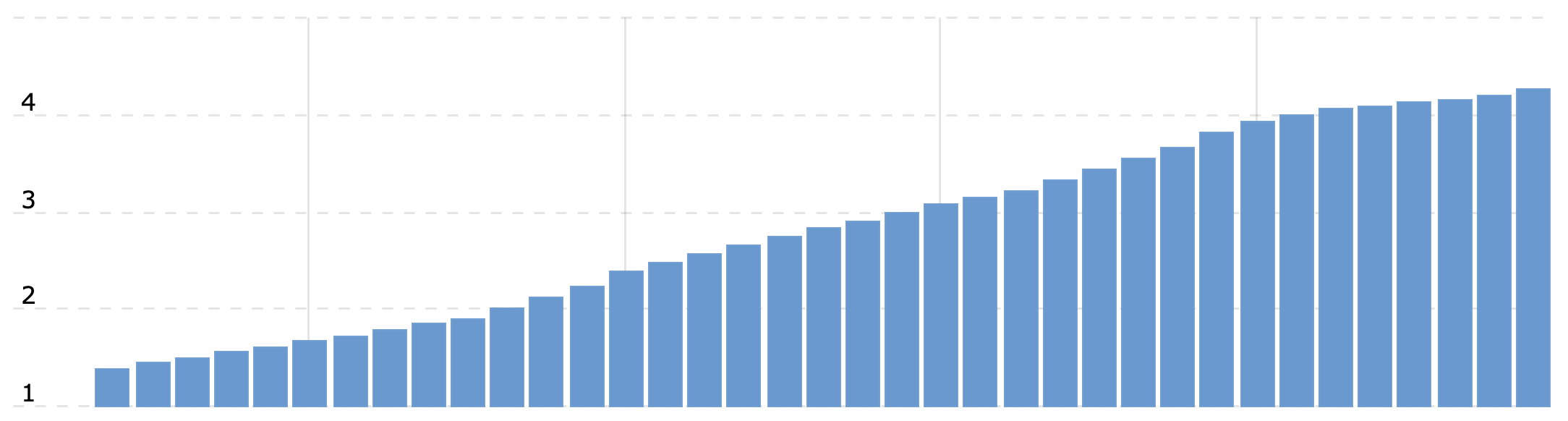

Editor’s Note: This article was written in 2014, so now in 2024 we can actually look back 10 years and see whether my GoDaddy prediction was correct. Annual revenue in 2014 was just under $1B, and in 2024 it is about $4B, so indeed they did not 10x—didn’t even 5x—over a ten-year period. Also, GoDaddy expanded into several additional product lines; had they “done what we’ve always done,” the growth would have been even lower. Their growth since 2014:

Figure 2: GoDaddy’s annual revenue, in billions of USD, 2014-2024

You get 2x by assumption but 10x you have to prove. If you’re in the business of raising money, you actually have to prove it. But how do you prove something that we just agreed was unlikely?

One answer is having very fast growth. If you’re doubling every six months, you clearly have line-of-sight for more growth than just 2x. Your trajectory proves intense market demand is getting coupled with an ability to find and service it. If the underlying market is large and/or growing, you have a good case that 10x is already within reach, and innovation could potentially get you 100x or 1000x. And indeed, the companies who have shown that sort of growth at interesting size 1 have indeed shown 100x or 1000x size thereafter.2

This is why investors (and founders) wishing to build enormous companies are so fixated on hyper-growth.3 It’s the only way to have even the potential of building something enormous.

1 “Interesting size” doesn’t mean going from 10 customers to 20 in six months and then being proud of your “rapid growth.” Going from 1000 to 2000 in six months is more like it.

2 With 10 years of hindsight, our company WP Engine was another one of these which experienced hyper-growth since hitting $1M ARR, and achieved 100x that six years later.

3 And “exponential growth,” though that is a misnomer.

Another way to break the Lindy Effect is to change something substantial. I think of this as expanding into an adjacency. As explained in that article, this means keep one foot planted in the areas you’re already strong, and expanding into something new, risky, but with much higher upside than incremental improvement on the existing business.

Of course not everyone cares about building something that services a million customers, or cares to expand into other areas for the sake of growth. Nor should they.

Even so, the Lindy Effect is helpful understanding what will be easy, and what will require something new.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/lindy-effect/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF