In command

When a founder or CEO or team leader is “in command” of her business, I don’t worry about that business, regardless of its challenges.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you always meet your own expectations for yourself or your team. It means you have expectations of yourself and your team, and when you don’t meet them, it bothers you, and you react.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean the metrics are always healthy, nor even that they’re moving in the right direction. It means you’ve already thought about what to measure and you’re watching the things that really matter. When metrics go awry, you’re the first one to identify that, and are already taking action in proportion to their importance and how far off the mark they are.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean the product has no bugs. It means you have a list of 100-1000 bugs, and the reason you’re not working on them is that you’re working on the top three that matter most.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you’re always the smartest person in the room. It means you’ve hired a team of great people who can challenge you and bring diverse perspectives to the table.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you never make mistakes. It means you’re proactively on the look-out for mistakes, and call them out when you find them, so that now you can rally many people in finding solutions, and make a change.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you never feel overwhelmed. It means you recognize when you’re overwhelmed, take steps to manage your stress, and seek support when needed.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean there are no problems with any team member. It means you’ve already talked to that person about it, and you’re working with them to change. Whether that means changing and staying, or changing by leaving. It means you’re proactively and intentionally solving for fulfillment for the whole team, which includes yourself.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean there are no existential threats looming over the business. It means you’ve articulated what those are because you sought them out and faced them head-on, and you’re mitigating the more likely ones with a few, logical actions.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean customers aren’t leaving due to lack of features. It means you’ve identified what those features are, which ones are consistent with your strategy, which ones lead to the ultimate benefits the customer is seeking, and that you’re working on one or two of them right now.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you’re always popular. It means you’re willing to make tough decisions, even if they’re not always well-received, because they’re in the best interest of the customer, the team, and the business.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you’re constantly telling people what to do. It means you’re acting as an editor, not a writer, unless being a writer is necessary to make progress. And if that is happening constantly, that you make a change on the team so that it’s not happening constantly. That might mean changing someone else, or changing yourself.1

1 If you’re constantly having to do someone else’s work, that’s your fault. Either you’ve hired incorrectly, which is your fault, or you have hired correctly and you’re not allowing them to do their job, which is your fault.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean your strategy is completely correct. It means you are adhering to the characteristics of great strategy. You have one, that is written down, that a normal person can understand, that people genuinely try to follow. When strategic flaws become apparent, you write those down too, and work on one or two at a time, updating your strategy calmly but purposefully.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean surprises never occur. It means when they do occur, it’s not due to negligence. It means something actually changed, or an important new fact was uncovered. Even better, if you were intentionally seeking new information, and thus seeking surprise.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you win every sale. It means you seek to understand the patterns in the wins and losses, and when those intersect with something consistent with your strengths and strategy and thus where you should win, you make changes so you can win the next such deal.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean every A/B test is a success. It means you’re running A/B tests and honestly assessing the results, so that you improve over time.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you don’t have a long backlog, most of which you’ll never get to. It means you’ve identified the few Rocks that are your bets on how to win strategically, and you have a system for prioritizing the rest, which also means doing almost none of the rest.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you know everything about your target customer. It means you are actively seeking out what they say and do, so you can understand them better, so you can make better decisions.

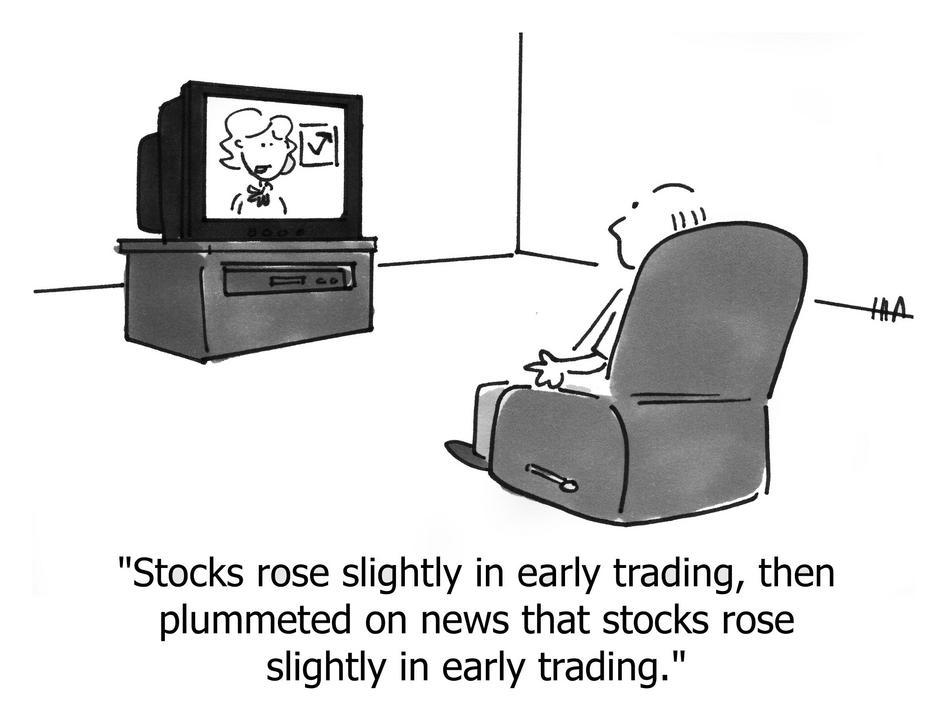

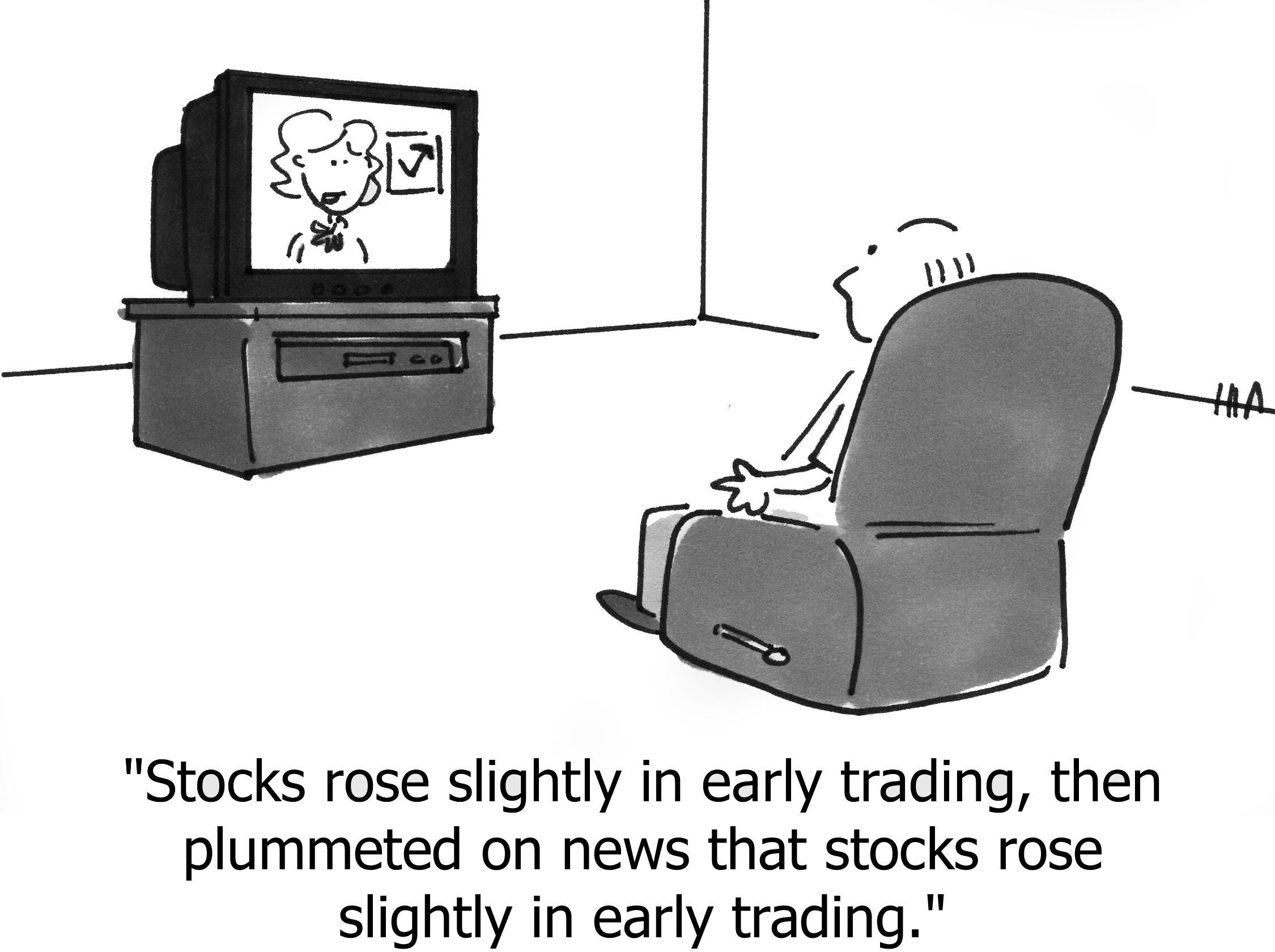

“Well when events change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

— Paul Samuelson, winner of 1970 Nobel Prize in Economics, about how his models of inflation during WWII kept changing over time, and he was criticized for “not being able to make up his mind.”

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you never change your mind. Indeed, a mind that never changes, is very likely wrong. It means you wrote down what you think, so that it’s more obvious when your mind needs to change, and then you communicate that change—both what and why. Even if just to yourself.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you do everything that stakeholders or even executives ask you to do. It means you listened with curiosity and empathy to what has been asked, having a system to reject bad requests and prioritize good requests, communicating that result and the rationale behind it.

Being “in command” doesn’t mean you’re “in control” of everyone and everything. It means you’re proactively seeking the truth, working rationally, and communicating.

This is how you create autonomy, coupled with accountability, with realistic expectations.

Strive to be “in command.”

https://longform.asmartbear.com/in-command/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF