Willingness-to-pay: Creating permanent competitive advantage for the right reasons

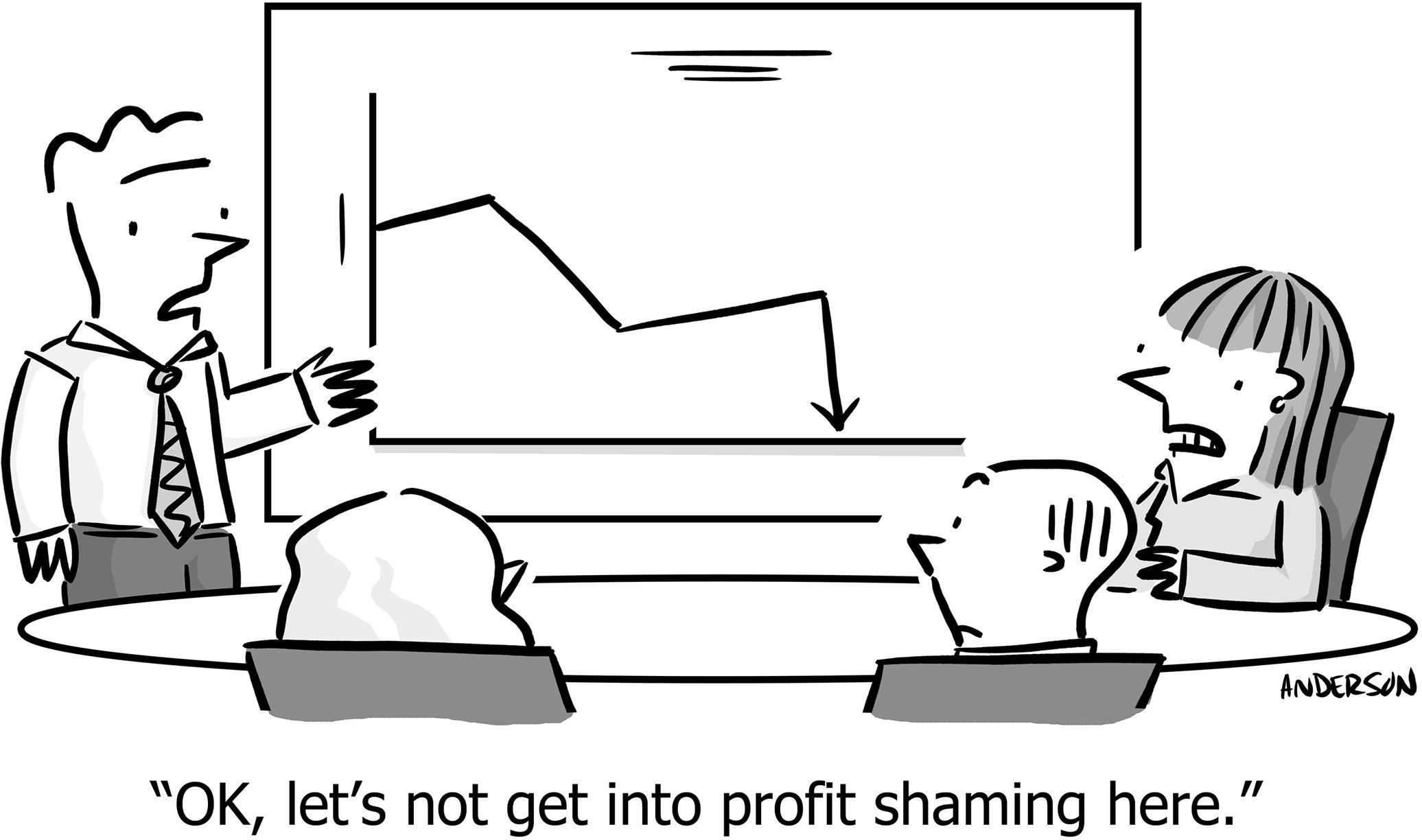

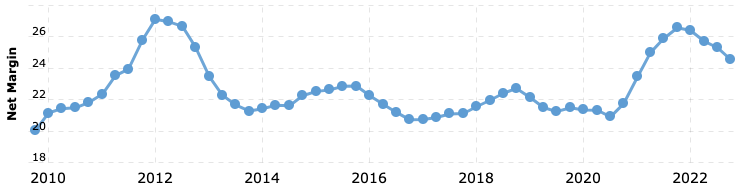

Traditional economics: WTP and Consumer Surplus

The best businesses deliver $4 of value, charge $2, and costs them $1 to do it.

It’s an obvious formula for both profit and happy customers, but what does “$4 of value” even mean?

Economists have labels for this formula:

Figure 1

Willingness-to-pay (WTP) is the maximum price the customer would have paid for the product, which the economist claims is how much the customer values the product. “Value” could come from anything—utility, pleasure, status, even irrational confusion. The economist claims that any transaction is evidence that WTP > Price, and the difference between those numbers is “Consumer Surplus.”

It looks trivial at a first glance, but I’ve come to believe that analyzing “WTP” is not only non-trivial, but also leads to very different strategies, business models, and outcomes.

“Willingness” to pay

I’m irked by this word “willingness.”

In 2015, Martin Shkreli, then-CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, bought the rights to the drug Daraprim, which for 62 years had been used to treat a deadly parasitic disease. He raised the price of a pill from $13 to $750, skyrocketing the typical cost of treatment from $1,000 to $63,000.

Martin Shkreli testifying before congress on a hearing on drug prices, before calling lawmakers “imbeciles”

“Profit” was his only justification for this abuse, in his own words:

“I think it will be huge…. So 5,000 paying bottles at the new price is $375,000,000—almost all of it is profit, and I think we will get 3 years of that or more. Should be a very handsome investment for all of us.” —Martin Shkreli, in communication with investors

Patients have no choice: It’s pay or die. The economist would say, patients objectively have a high “willingness” to pay. But is this how we should define “willing?”

And when patients cannot afford a $63,000 treatment, and therefore don’t purchase the drug, and die, should we say “well, I suppose they weren’t ‘willing’ to pay?” This phrase captures neither the intent nor the ability to pay, both of which are critical factors in questions of price, profit, and consumer surplus.

While there are many1 such examples, it’s more instructive to point out mundane, non-life-threatening examples of why “willing” is not the right word.

1 There were at least four egregious cases in 2015 alone. More recently, Moderna quadrupled the price of their COVID vaccines, its CEO Stephane Bancel saying that the new price is “consistent with the value” of mRNA vaccines at 45 times the manufacturing cost, after the US government paid them billions to cover the cost of developing the drug. Are we “willing” to pay even more? “Yes” in the sense that human life is valuable, but “no” in the usual sense of the word “willing.”

It happens with commodities, which economists say are a “perfect market.” When crude oil prices go up, prices at the pump go up immediately, even though costs haven’t yet risen. When crude oil prices go down, prices at the pump go down slowly, even after costs have in fact fallen. The same thing is happening now with eggs. Is that because we’re all “willing” to over-pay for gas and eggs?

It happens with bundling— often touted as a wonderful strategy. I never liked paying for cable TV, because it seemed expensive considering I still had to watch ads all the time. Most of the channels I paid for, I didn’t watch. Cable companies know that of course; they bundle channels specifically because they know consumers are not “willing” to pay for all of them. Because the content-owners have a near-monopoly, consumers have no choice. Even with modern streaming services the problem persists, because whether it’s Hulu Live or YouTube TV, it’s still bundled, and still the same price.

There’s also “willing” versus “able.” Perhaps many more consumers would be “willing” to pay $1000 for a fully tricked-out smartphone, but most are not “able.” This is a vital fact when determining strategy, business models, and company viability, but an economist would just say “few consumers are ‘willing’ to pay $1000 for a high-end phone.”

But it’s not all bogus. There is a genuine concept of being “willing” to pay more, and thus genuine “Customer Surplus.” I am willing to pay more for Anker products (power strips and chargers) because they’re extremely high-quality; I don’t even notice if there’s a competing product that is 20% cheaper. I’m loyal even though there is neither lock-in nor recurring revenue. People pay more for TOMS2 and Patagonia3 products because of their authentic missions. People routinely pay more for coffee that has a fair and sustainable supply-chain, because they’re willing to pay more to have a positive impact on the world, not just to consume the product.

2 Blake Mycoskie was vacationing in Argentina, when a knowledgeable American opened his eyes to the outsized impact that a lack of shoes has on poor children. Unprotected feet are susceptible to punctures and infection, and prohibit walking long distances, which in turn means one cannot go to school. He founded TOMS shoes, selling an Argentinian-style shoe, with the logo of the Argentinian flag, with a marketing strategy he dubbed One for One: Every time you buy a pair of shoes, TOMS would give a pair to a needy child. After TOMS’s financial success, Sketchers copied the strategy exactly, even down to the style of the shoe, the name (“BOBS”), and the altruism. Consumers were so outraged by this inauthentic strategy, Sketchers was forced to cancel the product line after just 24 hours (although they revived the brand later with a different mission). That strategy was individual to TOMS; it was irrelevant that the strategy was publicly visible and copy-able. TOMS has weaknesses— people complain about poor customer service and shoes quickly developing holes—but they win anyway on the strength of the individualized story.

3 Besides their publicly-lauded sustainable practices and an outdoor-worshipping culture, they even have a formal company policy to bail employees out of jail if arrested while protesting peacefully.

Indeed, genuine “willingness” creates the best, most durable, most profitable businesses. Consumers not only pay more, they’re happy to pay more, creating profit margin. They become evangelists, driving efficient growth. The company is resilient to competition, because consumers are buying for reasons other than “features” and “price.” The world becomes a better place, transcending a zero-sum game of winners and losers.

Analyzing the differences between these kinds of WTP yields insights that all products and companies can leverage to build the best strategies.

Three kinds of WTP

I divide WTP into three categories, each having different drivers, and much different strategic value:

Love

- Mission: the joy of supporting a change that’s bigger than all of us, or a community or movement you want to see flourish

- Reciprocity: when the company gives before taking, or gives more than it takes, or provides exceptional customer service, or is deeply human

- Exceptional design: a joy to use, a product that seems to genuinely care about your experience

- Exceptional quality: the pleasure and relief generated by reliability

- Personal identification: leveraging the company’s brand as visible component of your own personal brand

- Culture: supporting an organization that treats employees and vendors well 4

- Transparency: openness from companies sharing their ups and downs5

- Social or environmental impact: supporting sustainable, fair practices

- Community: a welcoming space where members learn and teach, support each other, create personal connections, grow their career or business, and be part of a tribe

- Ecosystem: wherein all members make more money or gain more prestige than had they not been part of the group

Result: Allyship. Consumers are genuinely happy to do business with you, and root for your success; when you make a profit, they cheer, because they want you to thrive; they advocate for you publicly,6 tying their personal brand with yours; they don’t even consider the competition; the old saying that “people buy from the person they like;” they would be OK with a small price-increase.

4 Counter-example: Walmart and Amazon, known for exploiting workers and suppliers

5 Often used by solopreneurs or bootstrapped companies in their early days, with Buffer being the most extreme (and well-loved!) example, sharing everything from salaries to strategy to monthly revenue.

6 This single tweet demonstrates this with thousands of responses.

Utility

- Cheap: even if quality and functionality is low, it’s better than not having the product

- Integrations: providing functionality while also more difficult to switch vendors

- System-of-record: being the official place for important data, making it risky and expensive to switch vendors

- Training: invested in having trained an organization, making it expensive and disruptive to switch vendors

- Market-share leader: the social-proof of selecting the market-leader is a reason to buy

- Location: coffee inside the airport is more expensive than on the street corner

- Convenience: groceries delivered to your doorstep are substantially more expensive than getting them yourself

- Simplicity: surprising ease is as delightful as it is useful

- Quality: a seamless experience with no defects is often worth paying for

- Risk-reduction: mitigating potential problems is difficult to measure, but valuable

- Unique functionality: a capability that no competitor can match is a sensible criterium for a purchase decision

- On-boarding experience: data shows that ease and reciprocity results in higher WTP

- Familiarity: having used a product or a workflow paradigm for years, it is the comfortable way to work

Result: Fair exchange of value. Your product is useful and not excessively painful; the “devil we know;” getting your money’s worth; easier to stay than to leave, and no particular desire to leave.

Coercion

- Contract lock-in: retaining your business through paperwork rather than by choice

- Data lock-in: retaining your business by holding your data hostage rather than by choice

- Effective monopoly: being the only feasible option7

- Effective price-fixing: breaking the so-called “free market”

- Middle-man: placing yourself in the middle of a transaction, increasing consumer price while decreasing supplier’s profit8

- Bundle-stuffing: combining many things the customer doesn’t want with the few they do want, to charge more in total9

- Scale Anti-Pricing: raising prices once an installation is at-scale, knowing that although an alternative might be more effective, more desirable, and cheaper, the one-time cost of switching is incredibly high

- Predatory Pricing: using lower-than-cost pricing to destroy competitors and ward off investors (funded by another business unit like Amazon does or by VCs as companies like Uber did), then increase prices once the competitive market has been decimated and customers have no choice.

- Patents: abusing a system meant to temporarily protect inventions to block normal competition.

- Corporate policy: once a product is written into a company’s formal policy (site-wide license or the only approved vendor for some application), that product “wins” even if every user hates it

- Government fiat or regulation: required by law10

Result: Adversarial. Customers want to leave; they idly comment that they wish some new competitor would arrive and disrupt you; they hate seeing your charges on their bill; they do business with you only begrudgingly; they lobby their boss to switch vendors.

7 This can be constructed purposefully, e.g. Uber spending tens of billions of dollars subsidizing rides to drive rival taxi and ride-share services out of business, so that they are the only option, and can raise prices, as they now have done.

8 A classic example is the person who buys a bunch of tickets to a concert, then resells them at 10x the price after the concert is “sold out.” Here’s an even more appalling example.

9 There is also a positive version of bundling, in which the items are mostly things the customer does want, purchased at a discount over buying each item individually, possibly with some useful interoperability.

10 Here Uber is an example of “love,” breaking the “coercive” stranglehold of taxi industry regulations.

All of these things contribute equally to the economist’s definition of WTP: The customer is in fact paying, and might pay more if you raise prices. But strategically they are completely different.

Effect on growth and competitive pressure

Love creates inexpensive, non-linear growth, because your customers are your allies.

You get repeat purchases, whether it’s a one-time revenue product or a loyal recurring-revenue customer. This creates growth with no additional marketing and sales costs.

You get word-of-mouth advocacy. When someone asks what to buy on Twitter, your rabid fans answer the question. When there’s a review site, your product ranks number one. When Customer Surplus is enormous, consumers reciprocate by selling new customers on your behalf.11 Once again, this is growth without additional marketing and sales costs. Furthermore, the effect grows as your customer base grows: A non-linear effect.

When a new competitor arrives, even when it is superior in features or price, your customers will stay, because they’re here for more than just the features and the price. This yields retention, which is another form of growth.12 There is a limit to this effect of course—at some point the product simply isn’t good enough—but it carries you through the vacillations of typical competitive one-upmanship.

11 Hollow Knight is a high-quality indie game, made primarily by just three people. Released in 2017, people still make YouTube videos about it in 2023. The soundtrack has millions of listens on Spotify. Everyone says it’s far too cheap at $15. Plus you get 4 expansion packs for free—something games normally charge for. Everyone repeats the story about how it’s just two guys plus one other guy who did the amazing music. Fans even begged them to charge more but they don’t—they’d rather be accessible, and people love them all more for it. The economist would say they should raise prices because they can. Yes they can, but it’s obvious that rabid fans generate millions of purchases, and that financial impact is so much larger than closing the WTP/Price gap to “demonstrate you have market power.”

12 Don’t believe me? Look at the growth curve of any startup that went from 7%/mo cancellation to 2%/mo.

Utility grows existing customers, and is neutral-to-positive on attracting new ones.

As an organization grows, it will naturally buy more seats of software for teams in customer support, sales, engineering, and so on. It will naturally buy more infrastructure and incur more credit card transaction fees. This isn’t a negative, and does creates internal growth, which is a powerful growth-driver for any business, especially at scale.13

But, a customer’s willingness to buy another ten seats of JIRA doesn’t imply the customer is going on forums, spending personal credibility to advocate on your behalf. And it doesn’t mean they won’t take a look at an interesting new competitor.14

13 At scale, new customers can be added only so quickly, whereas you have an enormous existing customer base, so growth inside the base is a larger factor than growth from new customers.

14 Indeed, new JIRA competitor Linear has quickly amassed a rabid fan base on the basis of exceptional UX. It’s easy to imagine JIRA users trying Linear and even advocating to switch, whereas it’s laughable to imagine a Linear user trying to convince their team to switch to JIRA.

Coercion causes your customers to be allied with competitors; they’re internally motivated to leave, so they will.

“Just give me an excuse.” Your customers, locked in against their will, cannot wait for a viable competitor to appear. They will go out of their way to switch, coming up with reasons why investing in the switch will pay for itself ten-fold, despite the cost. Exactly the case you don’t want your customers building.

When your contract is up for renewal, you should be very afraid. When someone asks on Twitter what tool they should use, your customers say: “Well we use X, but don’t make the same mistake!”

You are constantly vulnerable to disruption, even by mediocre competition. This is the weakest position you could be in, because you’re coercing customers instead of delighting them.

Profit done right: Create more WTP, then split it with the customer

“[When you increase WTP], you’re adding value for the consumer, and then figuring out how to split that with the consumer.”

—Michael Mauboussin, interviewed on the Invest like the Best podcast.

Creating value for the customer comes first. Then—and only then—you can decide how to “split it with the customer,” either leveraging Consumer Surplus for advocacy, high-retention, and growth, or indeed by raising prices.

When you create that value through Love or Utility, this is both sustainable and profitable. When it’s through Coercion, it is temporary at best.

The strongest organizations have all three. For example, Apple generates Love through appealing design, being a statement of personal brand, and maintaining the highest standard of privacy even if it means the product is less functional or interoperable. Apple also leverages utility, becoming familiar and convenient (and thus a mental effort to switch away), and trying to become the center of everything from family photos to shared files to 10,000 notes to the common way to purchase things, creating a form of “lock-in” that feels useful rather than evil. But it leverages Coercion as well, as users are locked-in even when they’d prefer not to be, unable to export data from apps like Notes, and being forced to buy new devices as older ones suspiciously stop working well after applying new (mandatory) operating system upgrades, and changing the connectors on charging cables every 5-10 years.

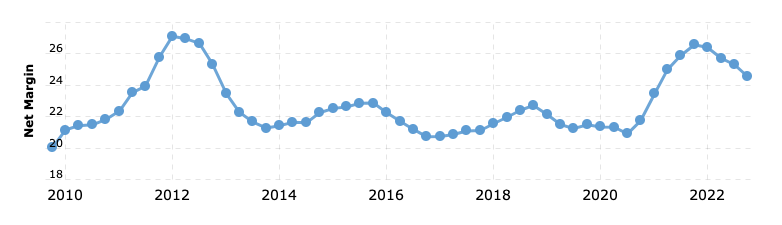

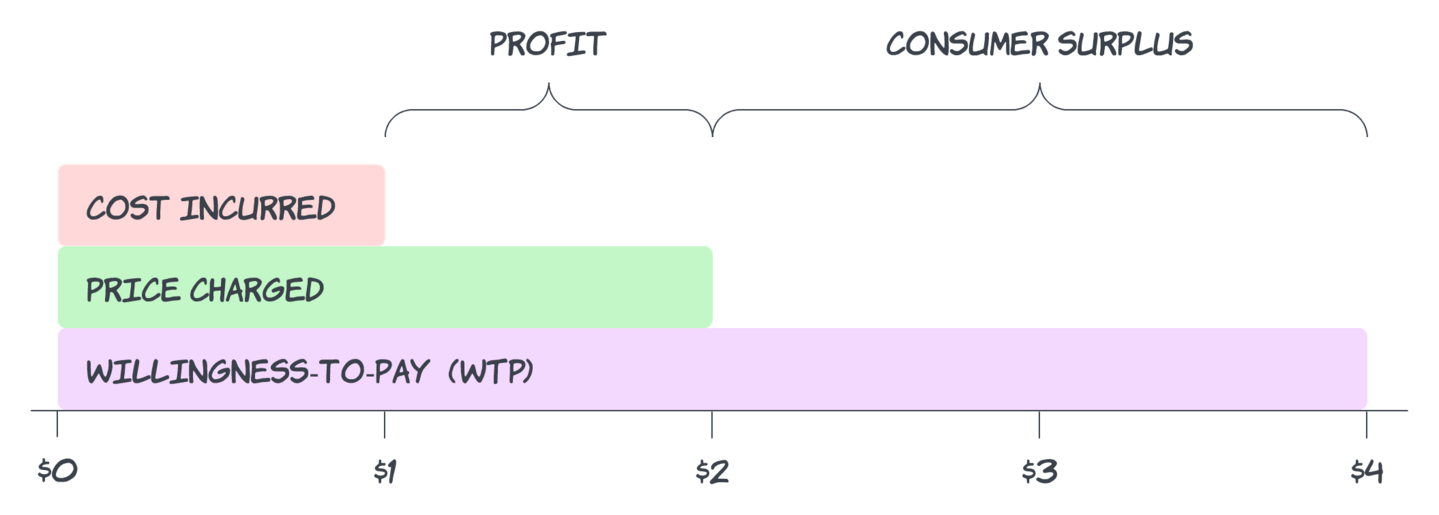

In any case, Apple has increased WTP in all three ways over the past ten years, and they’ve split that with their customers, as evidenced by a consistent profit margin:

Figure 2: Apple’s net profit margin:

If they were increasing prices faster than WTP, profits would have increased.

Even the cold-blooded capitalist should eschew Coercion

Here’s why Love and Utility results in more valuable companies, even though it prioritizes Consumer Surplus over profits:

Imagine there are two companies, alike in every way: Same product, same industry, same market, same number of customers at the same price, at the same costs, and thus the same revenue, same profit, and same WTP. The only difference is:

- Company’s WTP is generated only by Love.

- Company’s WTP is generated only by Coercion.

Which one is most likely to grow in volume and profit over the next five years? Which is more likely to capture more market share? In other words, which is the better investment for a Venture Capitalist?

I’d pick (1). I know their customer base will help them grow efficiently, while competitors look on helplessly, unable to convert customers even with the lure of unique features and lower prices. Whereas I know (2)’s customer base will be trying to leave, praying another competitor comes to save them, publicly warding away potential customers from repeating their mistake.

It is also possible for (1) to add Utility or even Coercive WTP to their strategy, further strengthening their position, whereas it is much more difficult for (2) to generate Love starting from their current position. It’s not that Coercion is never an appropriate ingredient, but rather that the other two are better.15

15 It’s like the Agile Manifesto: When it says “Working software over comprehensive documentation,” it isn’t saying “Documentation is bad.” Rather, it’s saying “Working software” is more valuable, so that’s where we should spend most of our energy.

Love beats Coercion, even as cold-blooded, money-grubbing capitalist investor, indifferent to ethics or the betterment of the world.

And yet Love makes money while in fact bettering the world, and making everyone happier.

So choose Love by building it into your strategy, investing in it, and then reveling in what you’ve created.

Appendix: Relationship to other frameworks

You can apply this concept directly to your strategy, and merge it with other techniques.

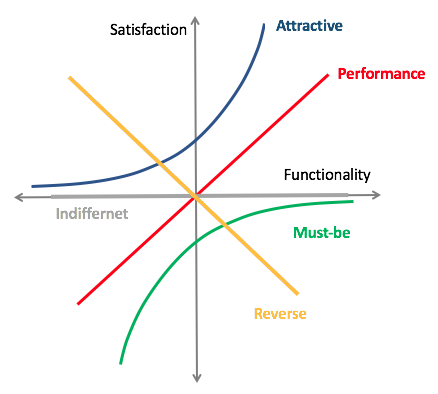

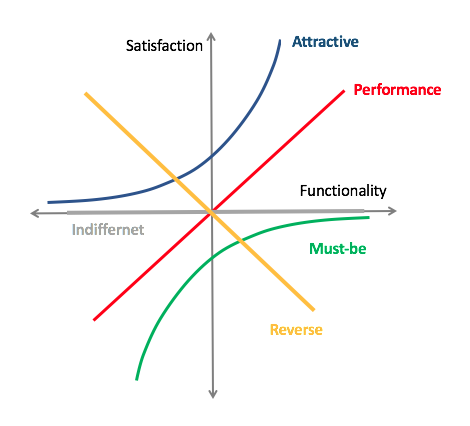

Kano (Figure 3)

“Love” feels a lot like Kano’s “Delight”—a joyous, perhaps even unexpected upside. “Utility” maps to “Performance”—where the more of it there is, the more value it is to the customer. “Coercive” maps to “Inverse”—something that customers actively dislike, even though you gain the selfish corporate benefit of retention.

Figure 3: The Kano model

Moats

Many of these things sound like moats, and for good reason: Increasing WTP of any type increases your ability to capture and retain customers. The more forceful (whether positive or negative), the more that becomes a permanent advantage that others cannot dislodge. No one can take away a fantastic brand, and government fiat can last for decades.

An interesting example is “network effect,” because it shows up in all three types:

- “Love” network effects include community and ecosystem, where participants help one another personally and professionally.

- One “Utility” network effect is a functioning marketplace, so e.g. eBay was for decades the destination having the greater number of buyers and sellers of collectable objects, and thus genuinely the most useful place to transact. You might not “love” eBay, but certainly people went there because it was useful, not because they were forced to.

- One “Coercive” network effect is when choice is limited to “preferred vendors,” creating a cartel rather than creating choice. For example, the United States health care system features insurance companies who each support their own network of doctors. A consequence is that switching insurance can mean you have to switch family doctors—an unnecessary and “value-destroying” activity as an economist would say.

Start with “Why”

“Love” reinforces the Simon Sinek’s admonition that companies must “Start with Why,” i.e. understand and articulate its higher purpose, it’s mission, because when that’s strong and important, when it permeates everything from its market-positioning to its culture to its employees, it’s extremely powerful, and impossible for a competitor to destroy.

Example: Buffer has a relatively undifferentiated product and pays lower salaries than many people can get elsewhere, but their culture and transparency is second-to-none, and people want to be a part of that. Example: TruthSocial, which can’t pay salaries like Twitter, and doesn’t have the reach of Twitter, and has technical issues with downtime and slow innovation, nevertheless possesses a rabid fanbase because of the mission and community.

Blue Ocean Strategy: The six kinds of “buyer utility”

In Blue Ocean Strategy, W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne highlight six ways in which you can deliver “value” to customers. These are a subset of the more general reasons why people are compelled to buy, but it’s useful to emphasize the cases where the customer is benefiting directly:

| Blue Ocean Buyer Utility |

WTP Category | Commentary |

|---|---|---|

| Customer Productivity |

Utility | This category is too broad; it is important to distinguish between “more value” and “less cost.” Both contribute to “productivity,” but it is an order of magnitude more important to increase value. It’s also important to define value. |

| Simplicity | Utility | Included above. |

| Convenience | Utility | Included above, in several forms; for example “location” is a specific kind of convenience. |

| Risk | Utility | Included above. |

| Fun & Image | Love | Included above. |

| Environmental Friendliness |

Love | Included in a more expansive “social and environmental impact,” as nowadays (2023) it is more common for customers to make buying decisions on factors like Fairtrade, or purchasing from local or minority-owned business, or supporting businesses with specific values and public commitments, in addition to the idea of being friendly to the environment. |

Long-term engagement metrics

Many products wish to “drive engagement.” Some point to Facebook as the pinnacle of “growth hacking,” driving up numbers, often slipping away from Utility (to say nothing of Love) and into Coercive tricks.

But even at Facebook, solving for Utility over Coercion worked better. In a fascinating multi-year UX experiment, Facebook found that when they reduced the quantity of notifications (by keeping the quality high), it had the expected negative result on engagement: Customer satisfaction increased, but app usage decreased (because it was leading you back to the app less often). But, after a year, app usage actually increased and remained higher that it was before the change. Increasing genuine satisfaction created more engagement in the long run. They had to be patient to see the results; traditional “growth hacking” did not discover the best solution.

Many thanks to John Doherty for contributing insights to early drafts.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/willingness-to-pay/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF