Your customers hate MVPs. Make a SLC instead.

Disillusioned with MVP

Product teams have been repeating the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) mantra for a decade now, without re-evaluating whether it’s the right way to maximize learning while pleasing the customer.

Well, it’s not the best system. It’s selfish and it hurts customers. We don’t build MVPs at WP Engine.

The motivation behind the MVP is still valid:

- Build something small, because small things are quick and inexpensive to test.

- Get it into the market quickly, because real learning occurs only when real customers are using a real product.

- Trash it or hard-pivot if it’s a failure, or invest if it’s a seedling with potential.

MVPs are great for startups and product teams because they maximize so-called “validated learning” as quickly as possible. And while customer interviews are useful, you learn new things when a customer actually uses the product. But MVPs are a selfish act.

The problem is: Customers hate MVPs. Startups are encouraged by the great Reid Hoffman to “launch early enough that you’re embarrassed by your v1.0 release.” But no customer wants to use an unfinished product that the creators are embarrassed by. Customers want great products they can use now.

MVPs are too M and rarely V. Customers see that, and hate it. It might be great for the product team, but it’s bad for customers. And ultimately, what’s bad for customers is bad for the company.

Fortunately, there’s a better way to build and validate products. The insight comes from honoring the utility of MVPs (listed above) while giving just as much consideration to the customer’s experience.

SLC: Simple, Lovable, Complete

In order for the product to be small and delivered quickly, it has to be simple. Customers accept simple products every day. Even if it doesn’t do everything needed, as long as the product never claimed to do more than it does, customers are forgiving. For example, it was okay that early versions Google Docs had only 3% of the features of Microsoft Word, because Docs did a great job at what it was primarily designed for, which is simplicity and real-time collaboration.

Google Docs was simple, but also complete. This is decidedly different from the classic MVP, which by definition isn’t complete (in fact, it’s “embarrassing”). “Simple” is good, “incomplete” is not. The customer should have a genuine desire to use the product, as-is. Not because it’s version 0.1 of something complex, but because it’s version 1.0 of something simple.

It is not contradictory for products to be simple as well as complete. Examples include the first versions of WhatsApp, Snapchat, Stripe, Twilio, Twitter, and Slack. Some of those later expanded to add complexity (Snapchat, Stripe, Slack), whereas some kept it simple as a permanent value (Twitter, WhatsApp). Virgin Air and Southwest Airlines both started with just one route. Southwest Airlines is the most profitable US airline in history. Small, but complete.

The final ingredient, and the one most unlike MVP, is for the product to be lovable. People have to want to use it. Products that do less but are loved, are more successful than products which have more features and are disliked. The original, very-low-feature, very-highly-loved, hyper-successful early versions of all the products listed in the previous paragraph are examples. The Darwinian success loop of a product is a function of love, not of features.

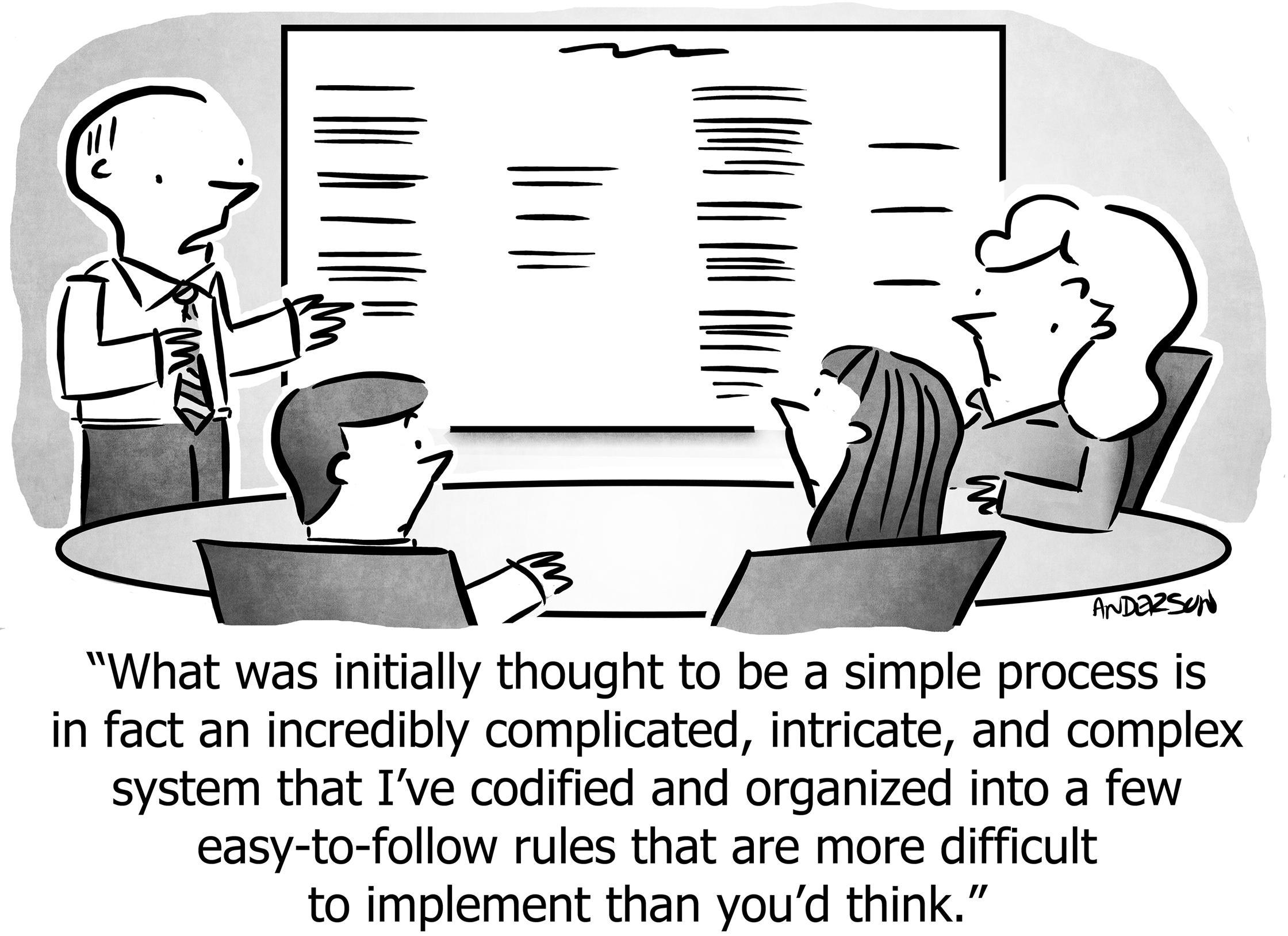

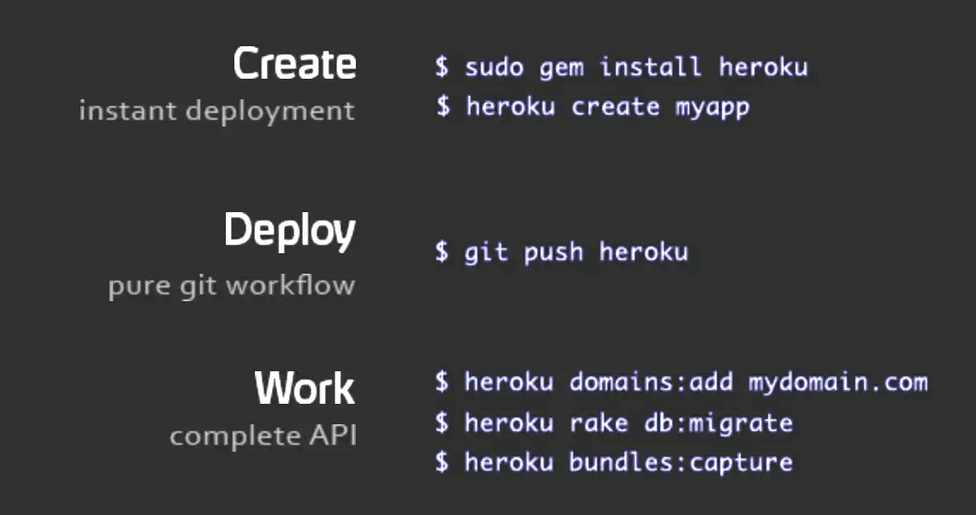

There are many ways to generate love. “Minimum” and “viable” are definitely not among those ways. The current-in-vogue way is through design: Elegant UX combined with delightful UI. But there are other ways. The attitude and culture of the company itself can generate love, such as Buffer’s blog with its delightfully shocking transparency (including open salaries and corporate metrics) or MeetEdgar’s blog genuinely helping entrepreneurs or HubSpot’s blog which early on was at least as instrumental to their customers’ success as the actual product. Another way is through a deep connection to the psyche of customers, like Heroku who broke with marketing tradition by filling the homepage with command-line examples instead of benefit-statements, thereby connecting instantly with their geeky target customer:

Figure 1

Read about “WTP” for many more examples of how to generate love.

From this reasoning, years ago I named what I believe is the correct alternative to the MVP: Simple, Lovable and Complete (SLC). We pronounce it “Slick.” As in: “What’s the ‘Slick’ version of your idea?”

SLC Summary

Simple, because complex things can’t be built quickly, and you must ship quickly so you can learn quickly so you can create the right product before you run out of money and willpower.

Lovable, because crappy products are insulting, and you didn’t start this company to make crappy products. The love overpowers the fact that the product is buggy and feature-poor. There are many wonderful, powerful, competitively-defensible forms of “Love.” Pick some.

Complete, because products are supposed to accomplish a job. Customers want to use a v1 of something simple, not v0.1 of something broken.

Life after SLC

Another benefit of SLC becomes apparent when you consider the next version of the product.

A SLC product does not require on-going development. It is possible that v1 should evolve for years into a v4, but you also have the option of not investing further, yet the product still creates value. An MVP that never gets additional investment is just a bad product. A SLC that never gets additional investment is a good, if modest product.

Many of the most successful software products in the world started as SLC, then grew in complexity, including examples we’ve already given (Google Docs and Snapchat).

The first iteration of Snapchat was a screen where tapping anywhere took a picture, that you could then send to someone else, at which time it disappeared. No video, no filters, no social networking, no commenting and no storage—Simple, yet Lovable and Complete, as evidenced by its rapid adoption. The insight of “no storage” was critical, but many people have theorized that the simplicity of the interface was also critical. The very fact that it was simple, while not sacrificing love-ability or completeness, caused its success.

Later they added lots of stuff—video, filters, timelines, “stories”, even video cameras inside sunglasses. It’s OK for products to become complex. Starting out SLC does not preclude becoming complex later.

WhatsApp was similar; it started with just a status message. Not a “post”, not a “chat”, no “timelines”, no “history”. Just “What’s up?”, hence the name of the app. They found people abusing the system to communicate with each other without paying for SMS messages, so they added chat. Dropbox started with just one folder that would (eventually!) sync across devices. Twitter had only the 140-character messages; things like replies and re-tweets were invented by users, implemented by convention, and only later folded back into the platform as built-in features. The examples go on and on.

SLC breaks Maslow’s Product Hierarchy of Needs

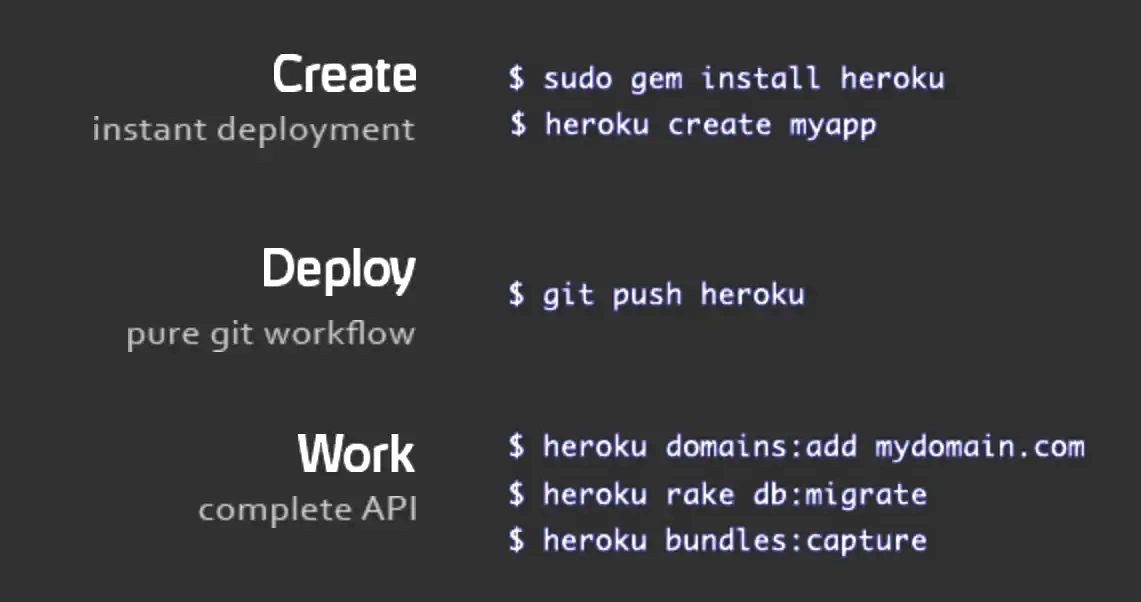

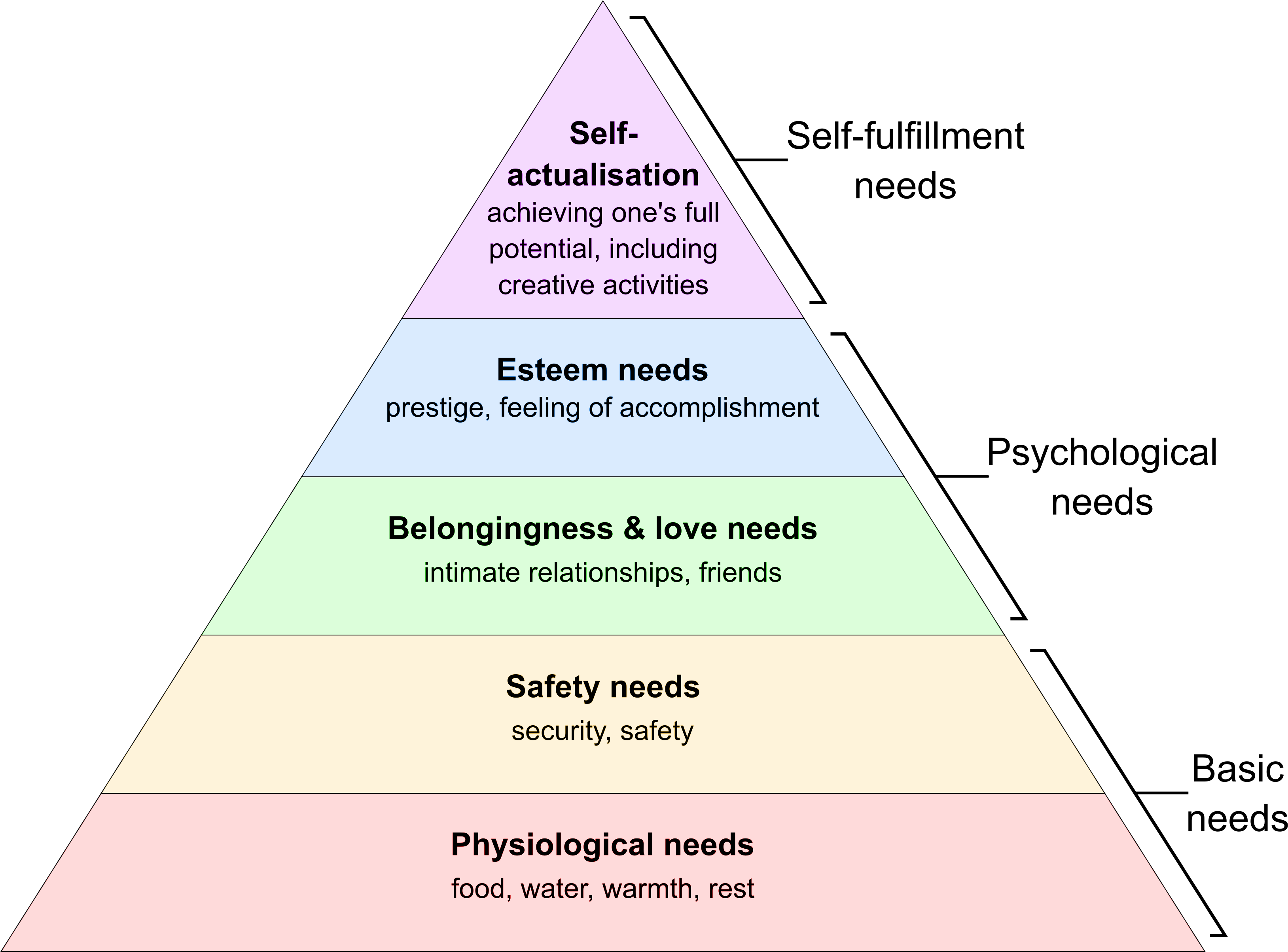

People erroneously believe that product development should work like Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

Figure 2: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

His insight is that you cannot achieve higher levels if you haven’t at least satisfied the lower levels: If you don’t know where your next meal is coming from, you’re not able to “creatively discover your true self.”

The framework is wrong, though this hasn’t stopped people from writing books and blog posts about it. “At the time of its original publication in 1943, there was no empirical evidence to support the theory.” “In a 1976 review of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, little evidence was found for the specific ranking of needs that Maslow described or for the existence of a definite hierarchy at all.” ( From Wikipedia, with its own references.)

It’s wrong for Product also, but we act like it’s true.

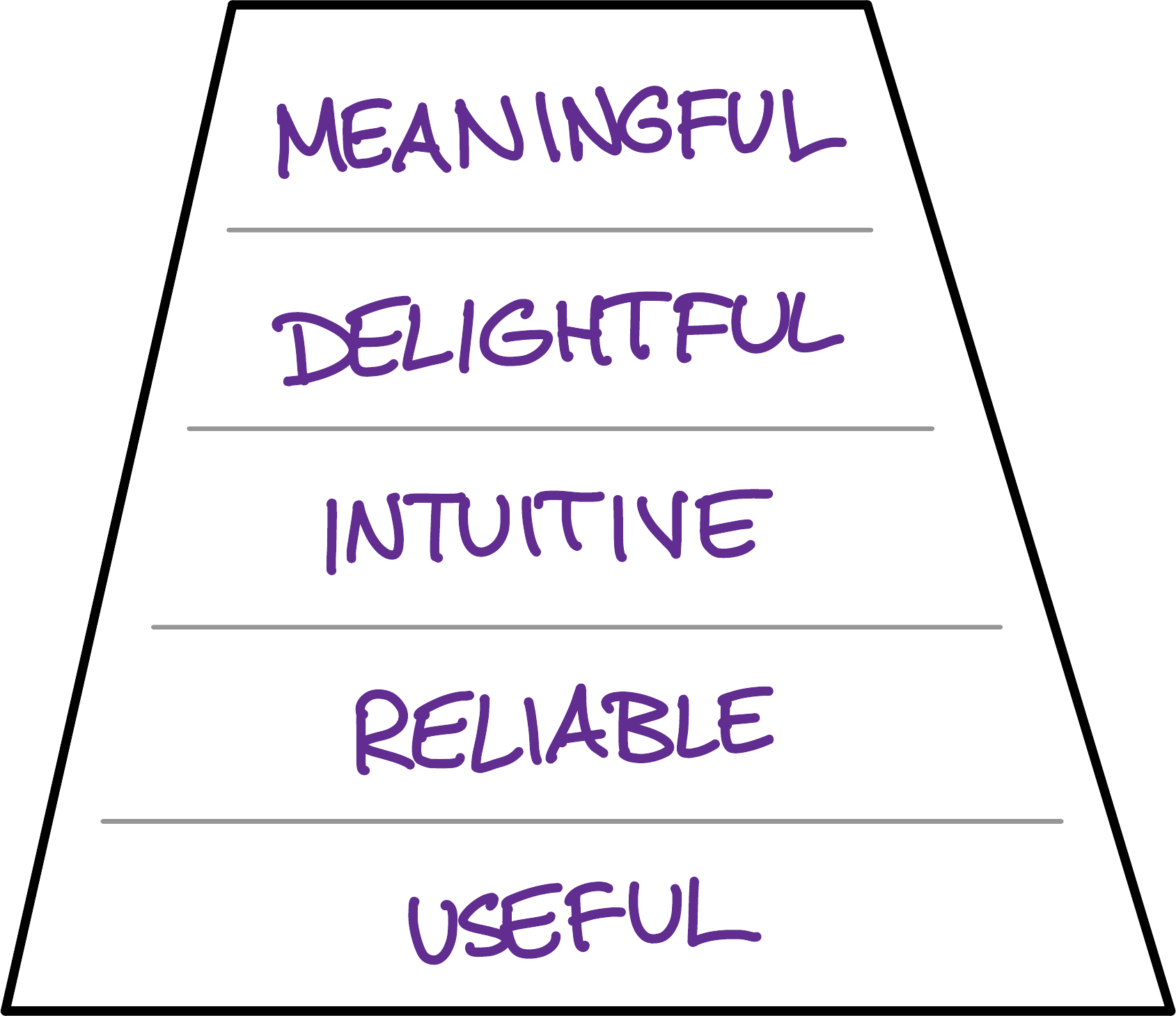

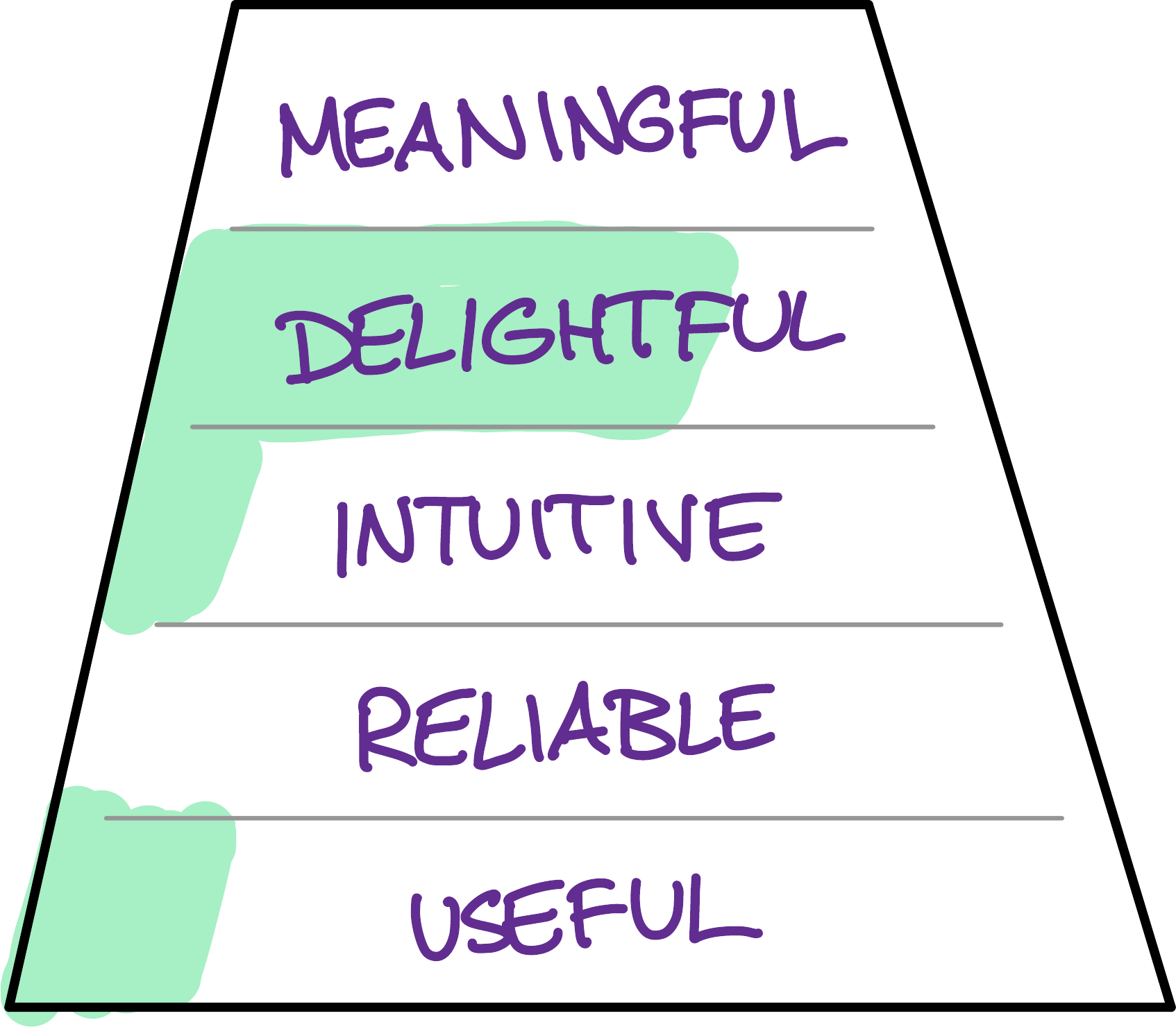

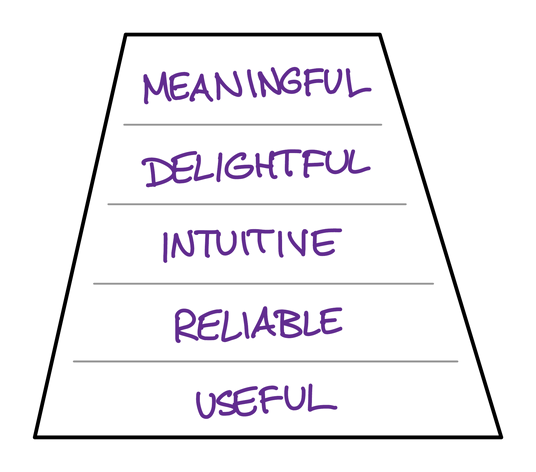

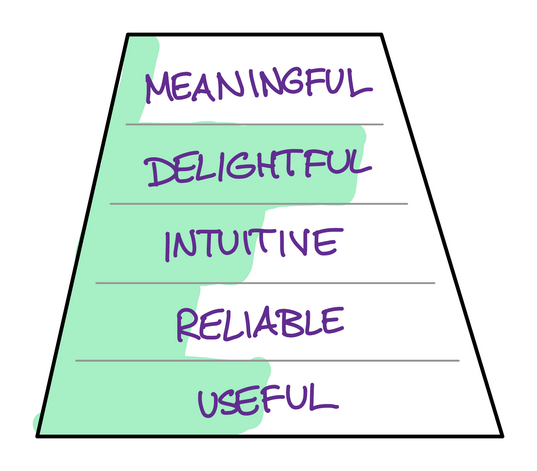

If we roughly parallel Maslow, the Product Hierarchy looks something like (Figure 3), defining the levels as:

- Meaningful

- Identity, belonging, higher purpose. “Larger than myself.” Impact. Legacy.

- Delightful

- Exceptionally wonderful to use, eliciting a strong positive emotion. It goes beyond being visually appealing or sensibly designed. It is at least extreme; it is likely surprising, because so few products delight us, especially in the business world. Perhaps a low bar makes delight easier to achieve, if we try.

- Easy to use

- Effortless and intuitive. Makes tech support obsolete.

- Reliable

- Always works as promised.

- Useful

- Fulfills a need; solves a problem.

Figure 3: Pseudo-Maslow Product Hierarchy

Following Maslow, we might say that if a product isn’t Useful then it doesn’t matter if it works all the time (Reliable) or is pretty to look at (Delightful), therefore “being useful” is the mandatory first “rung” of the ladder. No reason to do anything else, if you’re not useful.

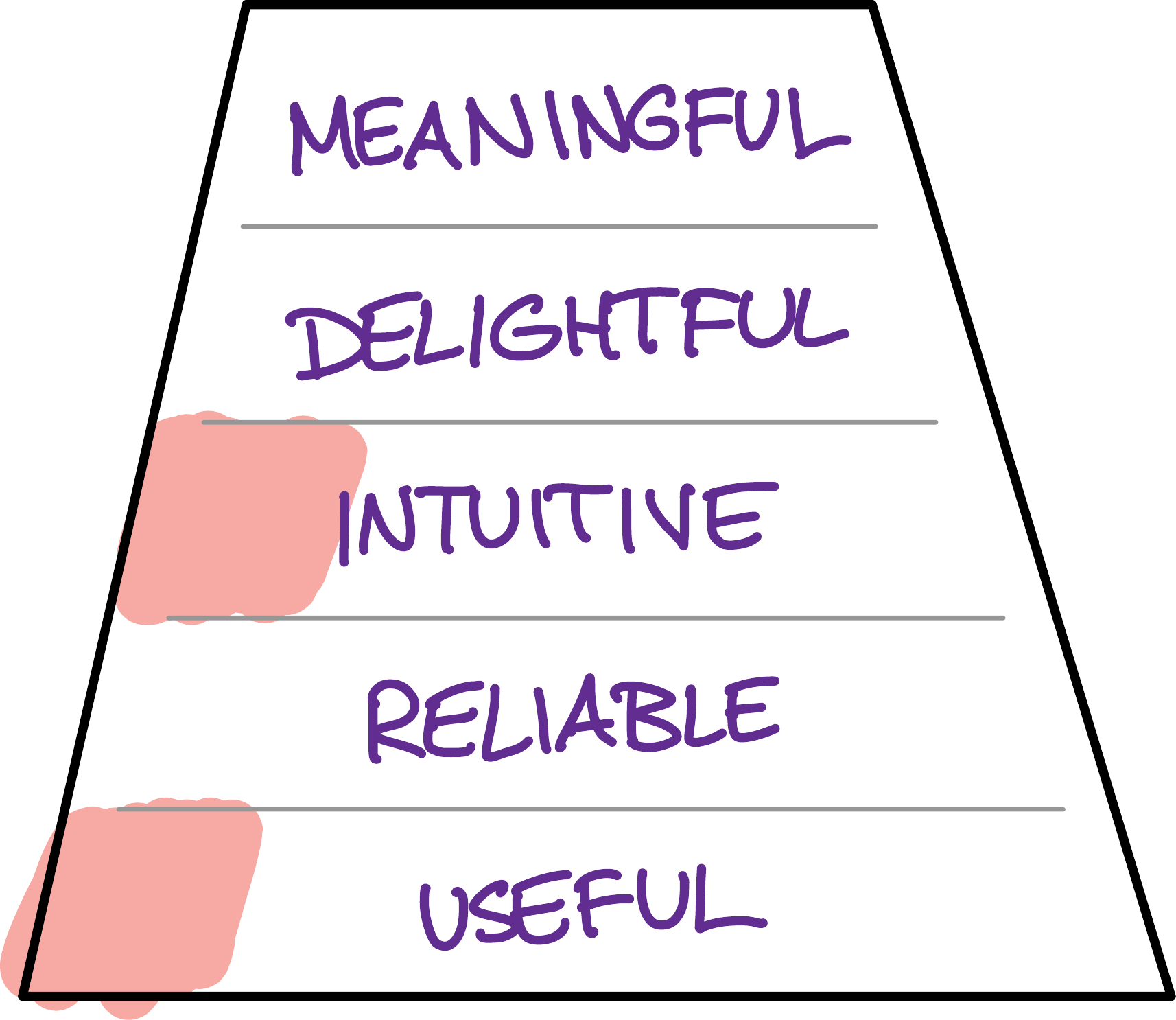

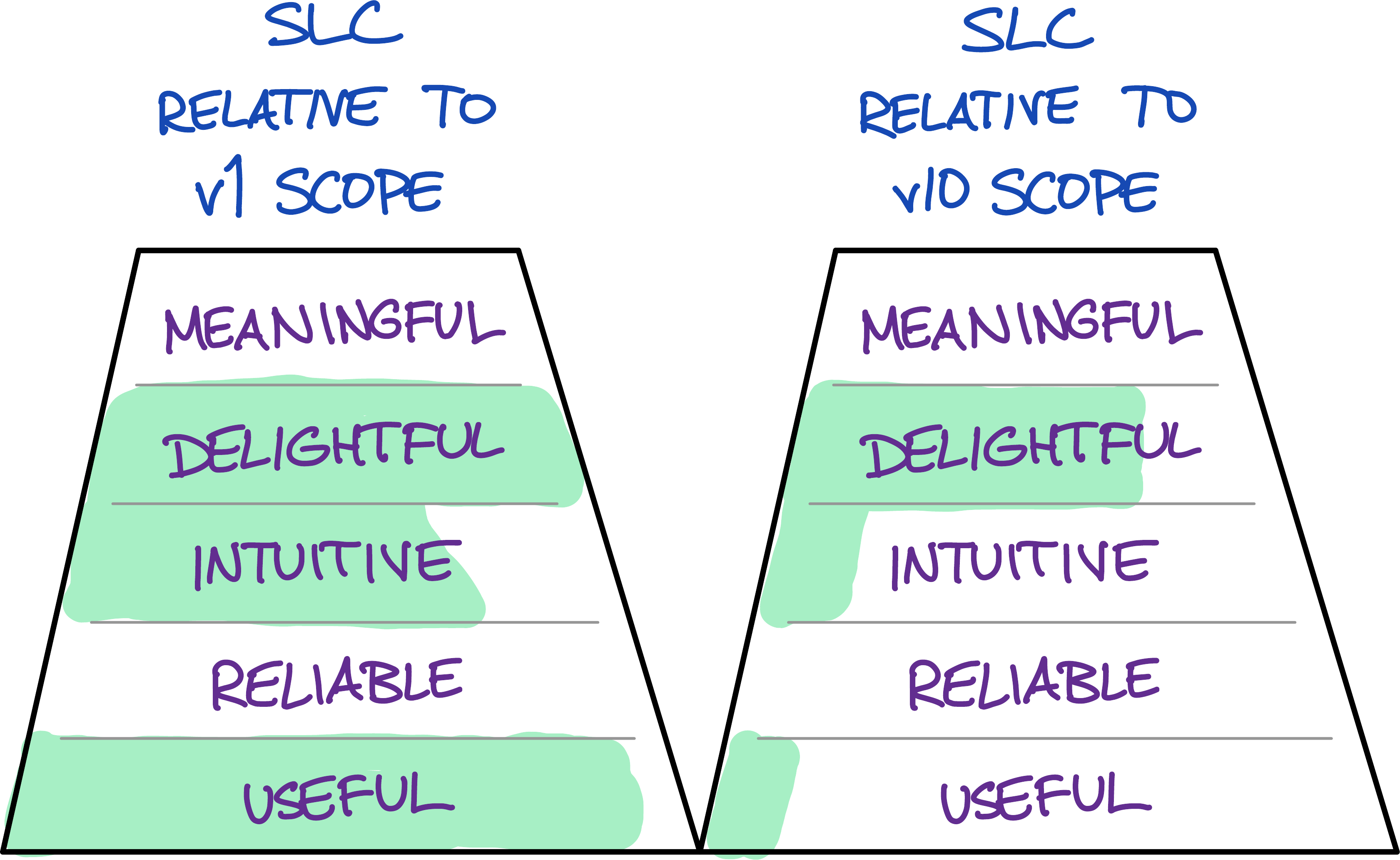

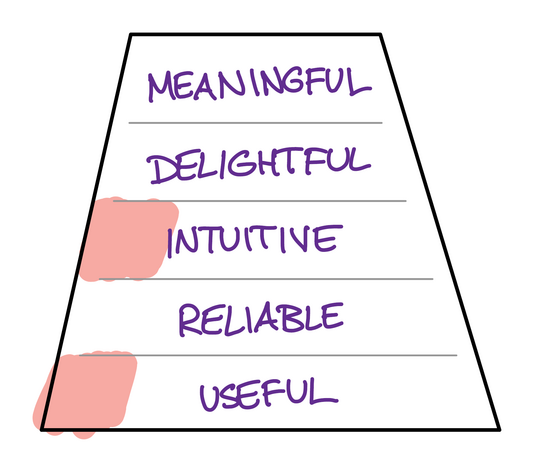

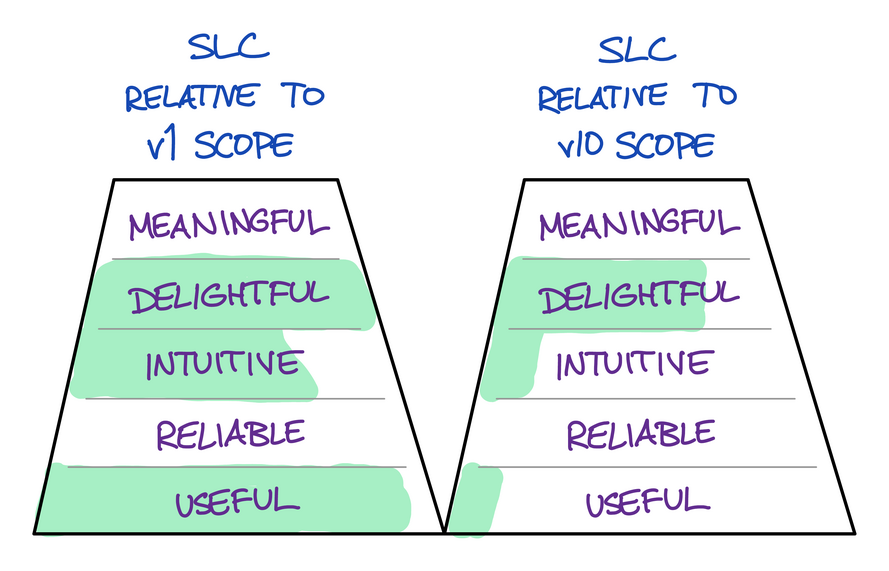

Indeed, that’s what traditional MVPs do: be minimally useful, disregarding all other levels as irrelevant until the first level is satisfied:

Figure 4: The typical MVP is minimally useful only, perhaps also being easy to try.

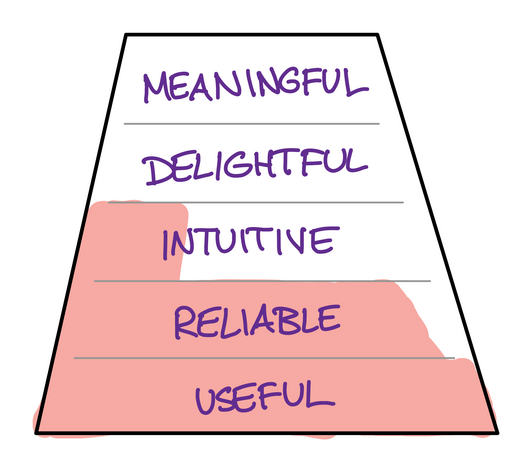

This MVP attitude is further justified by projecting its future. We can map the behavior of mature products, especially in so-called “Enterprise Software” where the person who chooses to buy it isn’t the person who is forced to use it, and therefore the bottom of the pyramid is valued and the top is not:

Figure 5: Mature products maximize the utility layers; do their users love it, or are they making an internal case for why it should be replaced with a more pleasant competitor?

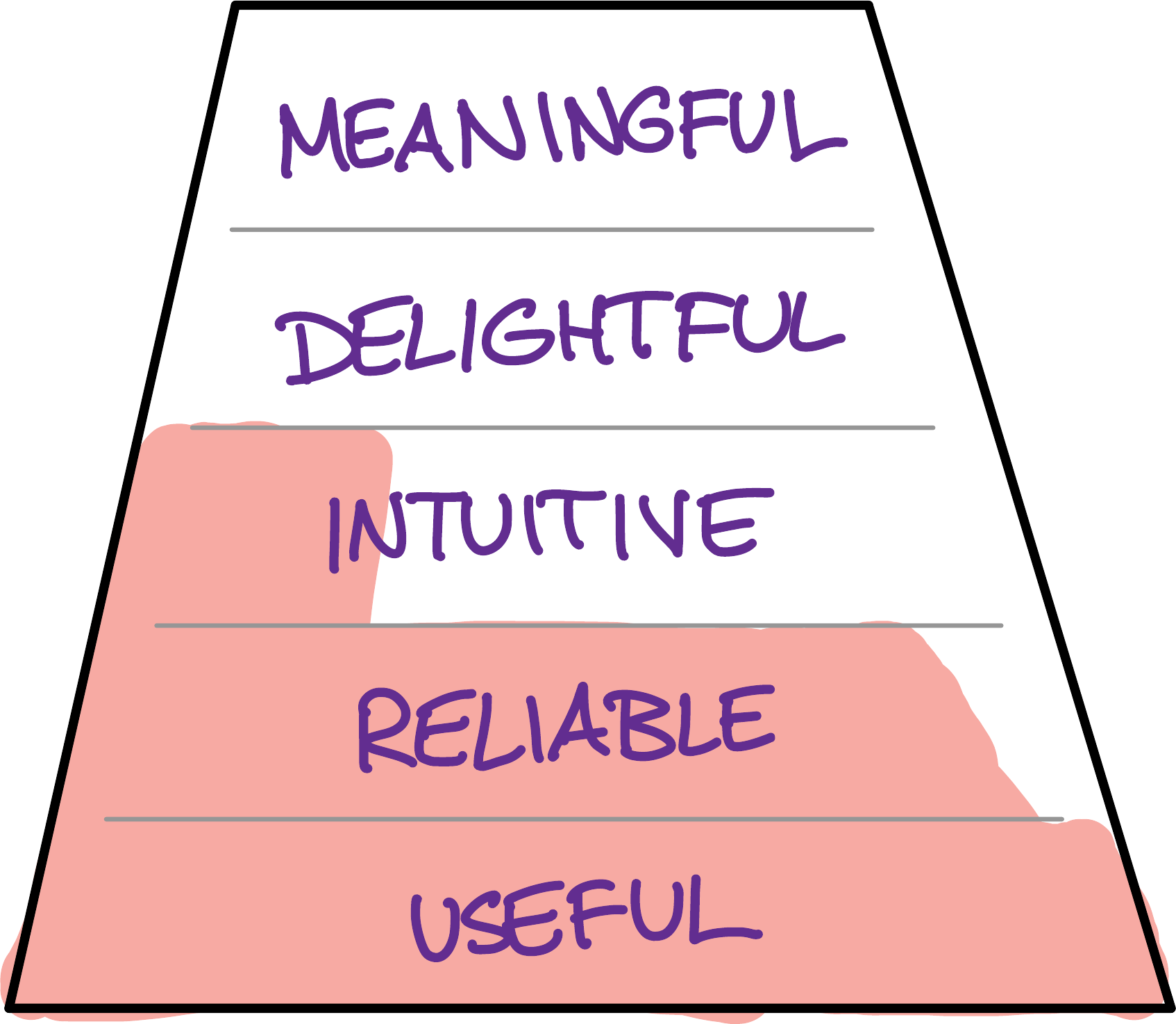

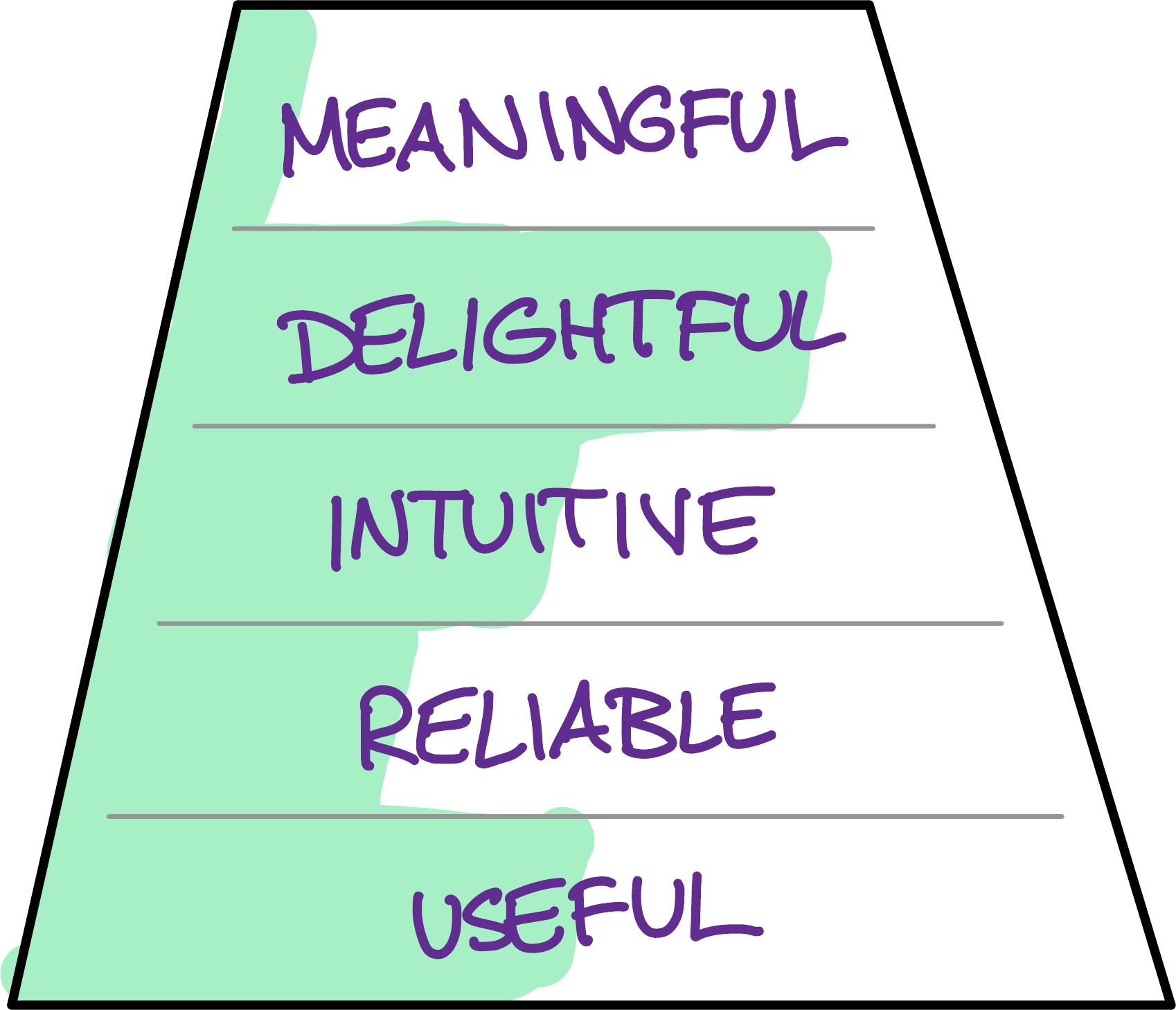

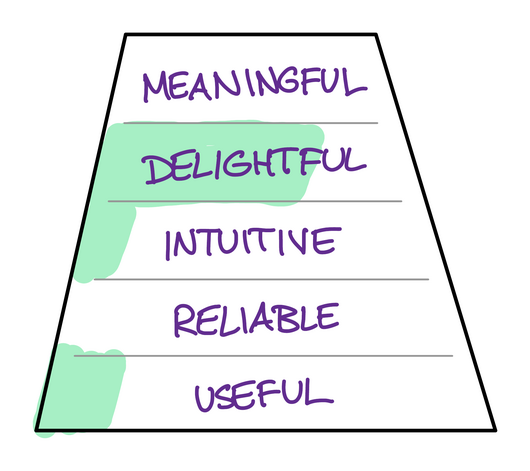

The SLC attitude is different. It agrees that we can’t fill much of any layer, because we need to ship it quickly and start getting feedback. But it emphasizes different layers:

Figure 6: SLC initially uses Delight to win the hearts of customers even though the product isn’t as useful or reliable as it will eventually be.

An SLC product evolves, already-happy customers are rewarded with additional features:

Figure 7: SLC evolves in a fundamentally different way, creating differentiation beyond feature-bullet-points.

Perhaps a better way to look at it, is that SLC is both Delightful and Useful on day one, albeit with a scope of “Useful” that is small enough to be “Complete”:

Figure 8: SLC as complete according to a narrow scope (left), but lacking features relative to the scope of a mature product (right).

Finally, a product that from inception is trying to “delight customers” is one that might actually deliver on the top of the pyramid: Meaning, personal identity, a higher purpose. You see this in products where people tie their identity to owning or using the product, not just in consumer brands where this is obvious, but in the way that people love Linear because it honors the developer (instead of the project manager), or the way they love Basecamp because they support the culture and attitudes of 37signals, or the way they whip out Moleskine notebooks because it connects them to a romantic ideal of the brooding writer, or proudly wear Patagonia gear as a badge of their environmental consciousness, or the way they argue over Vim vs Emacs as a badge of geekery.

Almost no company cares about creating meaning for their customers. Here’s how I know: What metric are they tracking—let alone optimizing for—that measures meaning? If none, then it’s out of sight, out of mind. Clearly, you can build large and even great companies like this; most do. But if you did care about that, SLC is the right way to start the adventure.

Why don’t more products prioritize delight? Utility is more obvious. Utility is what the customer’s budget is allocated to obtain. Delight requires insight and great design, not back-end optimization and a keen mathematical mind. It is a rare person who possess all of these abilities, or even values them in others. It is a decision to prioritize Delight over Utility; it is easier not to.

The “pyramid” is useful for mapping out where you’re going to spend your time, but we need not traverse it from bottom to top. Products that prioritize delight win over products that don’t.

It’s really another way of prioritizing the customer—the human being, not just their “job to be done.”

With SLC, the outcomes are better and your options for next steps are better. It might fail; both SLCs and MVPs sometimes produce that result because you’re running an experiment. But if a SLC succeeds, you’ve already delivered real value to customers and you have multiple futures available to you, none of which are urgent. You could build a v2, and because you’re already generating value, you have more time to decide what that should look like. You could even query existing customers to determine exactly what v2 should entail, instead of a set of alpha-testers who just want to know “when are you going to fix this broken thing?”

Or, you can decide not to work on it. Not every product has to become complex. Not every product needs new major versions every two quarters. Some things can just remain simple, lovable, and complete.

Ask your customers. They’ll agree.

Many thanks to Devan Stormont, Kathy Qian, and Khurrum Mahmood for feedback on this article.

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Simple eReader (Kindle)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Rich eReader (Apple)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF