Pricing determines your business model

It’s often said that you shouldn’t talk about price during customer development interviews. The usual justification is that your goal is to uncover the details of your potential customers’ lives and pain-points, whereas mentioning price diverts the discussion to budgets and operational things far removed from the customers’ day-to-day life.

But I disagree. Price is as important as any other feature to determine product/market “fit.”

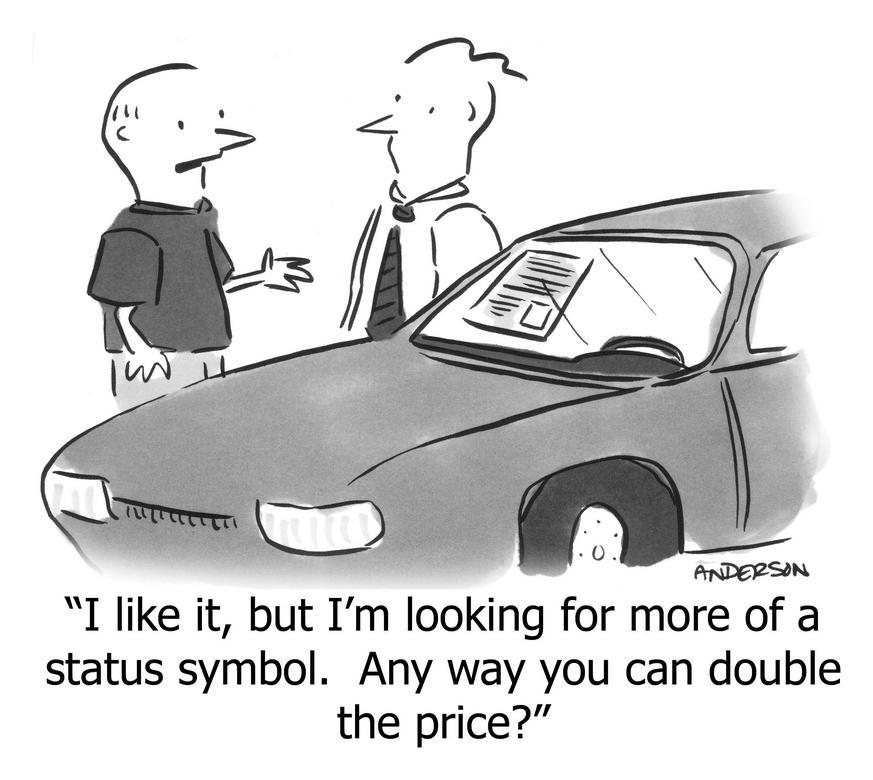

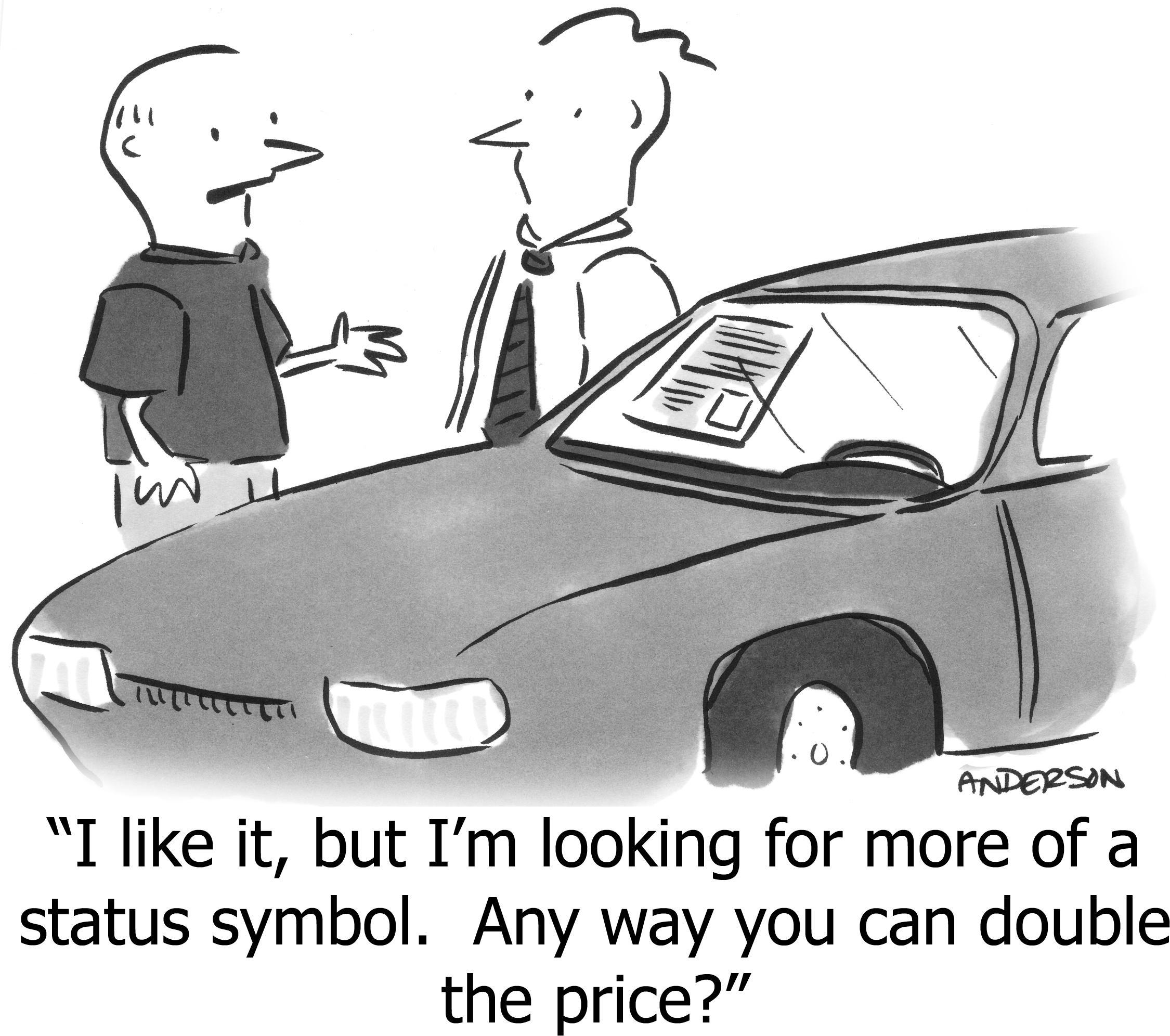

How many times have you heard someone agree that “it would be great if someone did X,” but when you show them a demo of X, but it costs $700, and they don’t buy? Or seen a review of an iPhone app hung up on pricing trivialities: “It would be pretty good at $0.99, but it’s not worth $1.99.” How many times have you seen someone struggle with an inferior product because they cannot afford the better one? Or struggle with the freemium version because they refuse to pay anything at all, even though they like and use the product? Or struggle with an inferior, expensive product that was purchased based on the salesmanship—“expensive must mean it’s better”—instead of craftsmanship?

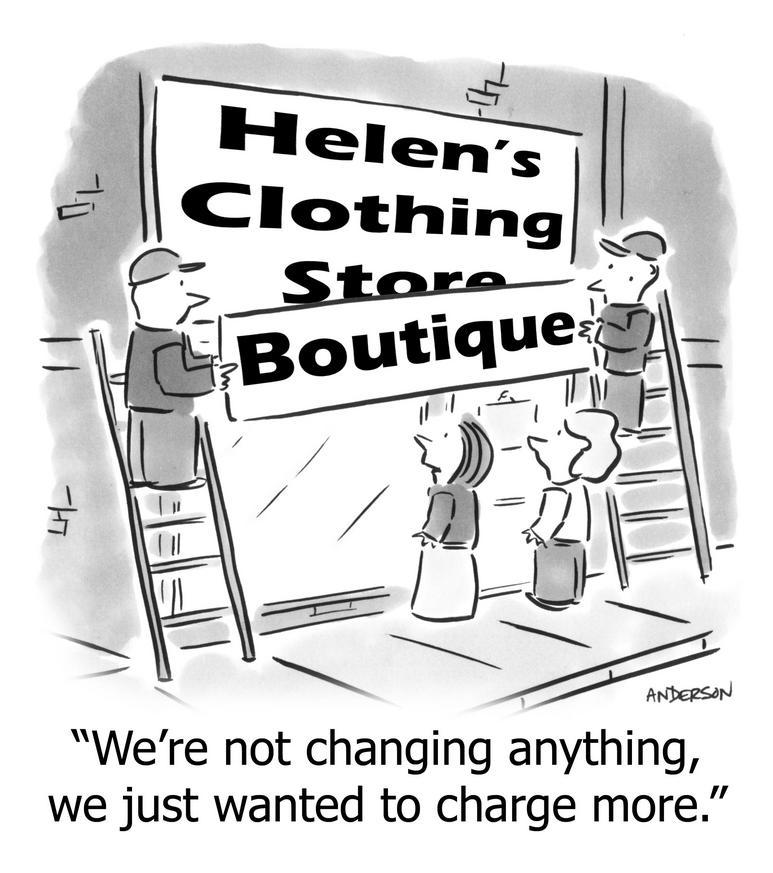

Price is inextricably linked to brand, product, and purchasing decisions—by whom, why, how, and when. Price is not an exercise in maximizing some micro-economic supply/demand curve, slapped post facto onto the product. Rather, it fundamentally determines the nature of the product and the structure of the business that produces it.

Consider the consequences of each order-of-magnitude of pricing:

$0/mo means your goal is to maximize growth (trust and usage) instead of revenue. Your product is designed with natural tripwires to trigger other pricing (Freemium model), or not (business model left as an exercise to your future self). Typically requires venture funding because you have no income, and if you’re successful you’ll need lots of people and tech to run the business. Even super-efficient outliers like WhatsApp (sold for $19B with 55 employees) and Instagram (sold for $1B with 13 employees) each raised tens of millions of dollars in venture funding. This is often B2C because the value is in quantity of customers, and there are 100x more consumers than businesses.

$1/mo means you can’t afford customer service and it must incrementally free to run the technology behind it, both of which have implications for the sort of product you have to build (e.g. simple enough to be self-service). Marketing and sales spend is nil (at least initially), so there has to be a reason it spreads by word of mouth, ideally virally as a natural result of using the product itself, or through vocally passionate early users, perhaps galvanized around a mission.

$10/mo means people see you as a cheap version of something else, but still expect a phone number. (Think: GoDaddy). Bootstrapped businesses can make this work (e.g. most shared hosting companies), but they only make interesting money at large scale (by definition, because it takes over 8000 customers to make only $1m/yr in revenue), which takes a long time to grow. So you can get to $10s of millions but it will take 10 years. (Again, like shared hosting companies.) This is a hard slog. If you want to scale faster you’ll need venture funding, both because of the anemic revenue, and because otherwise you can’t afford to advertise. Often bootstrapped companies of this type boast about having no marketing or sales departments, but the truth is they can’t afford it, and those companies typically grow slowly, often eclipsed by companies who can afford to grow 10x faster. In a huge market this is probably still OK because there’s enough customers for everyone to thrive in different ways. On the good side for this business model, often people will simply forget they have the $10/mo service even if they don’t use it, resulting in “free revenue” which at scale can be surprisingly substantial (yet again like shared hosting companies).

$100/mo means people expect to be able to call support, and if a competitor is substantially better, it’s probably worth the effort to switch. Also this is almost exclusively B2B unless it’s something “luxury.” Big companies can buy it without much consideration, but small companies need to understand the value, so you might need sales material to convince them, and a demo. I love this price zone for bootstrapped companies, because it’s low enough that you can address a broad business market, but high enough that you can get nicely profitable with a reasonable, achievable number of customers (e.g. 200-300), and you can afford to spend money acquiring them.

$1,000/mo means only medium to large companies can afford it. They’ll have buying processes around annual budgets, approvals, ROIs, demos. You will be compared to alternatives and weighed. You’ll be asked to give a discount. You need to be a part of that conversation which means a real sales force, sales materials, impressive logos, case studies, and referenceable customers. Features might need to include things that big companies need that others don’t, like role-based access privileges and integration with LDAP. This can be a surprisingly difficult zone to become profitable in, because the sales and marketing motions and engineering costs are the same as for much larger sales, but without the attendant revenue.

$10,000/mo means larger companies only. It’s unlikely the product is sufficient out-of-the-box, so you might need in-house professional services or to partner with consulting firms for implementation—constructing the “Whole Product” in the language of Geoffrey Moore. If something goes wrong they’ll cancel and not be willing to pay out the rest (no matter what your contract says; what are you going to do, sue your customers?). It’s possible to achieve this price-point with mid-sized companies if it’s usage-based (e.g. ZenDesk, JIRA, Box, Slack) or performance-based (e.g. marketing optimization), so the product itself needs to create and then demonstrate value to earn that result.

$100,000/mo means Global 2000 only, large-scale projects that require multiple departments for decision and approval, long sales cycles (9-18 months) which requires massive cash outlay as you bide your time. Likely starts as a pilot or proof-of-concept, which hopefully you can get paid for, and which needs to be convincingly successful, perhaps battling against another pilot with another vendor. You’ll need on-site visits even in this day and age of video-conferencing. Examples: WorkDay (much of revenue is consulting), IBM.

So which is better—higher or lower or in the middle? That’s a better question. Here’s something resembling an answer.

The main thing is to understand that price is linked to everything, and bring it into your customer interview process. Talk about their expectations of cost, and why, who would write the check, who would need to approve it, whether an ROI argument would be welcomed or scoffed at, or what would need to be changed (if anything?) to justify doubling your price (at which point, maybe you should do that an in fact double your price).

Price is not an afterthought, it is essential business design.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/pricing-determines-your-business-model/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF