How much of success is luck?

It’s amazing how often “luck” comes up when people find out I started Smart Bear.

“You’re lucky to have your own business. I hate my boss.”

“You’re lucky your business is still doing okay in this recession.”

“You’re lucky that you sold your business when you could.”

I wanted them to be impressed with the hours I put in, with the ideas I had, with my amazing product sense, with the way I handled customers, with my 50% sales close rate, and how I overcame the mental stress of bootstrapping.

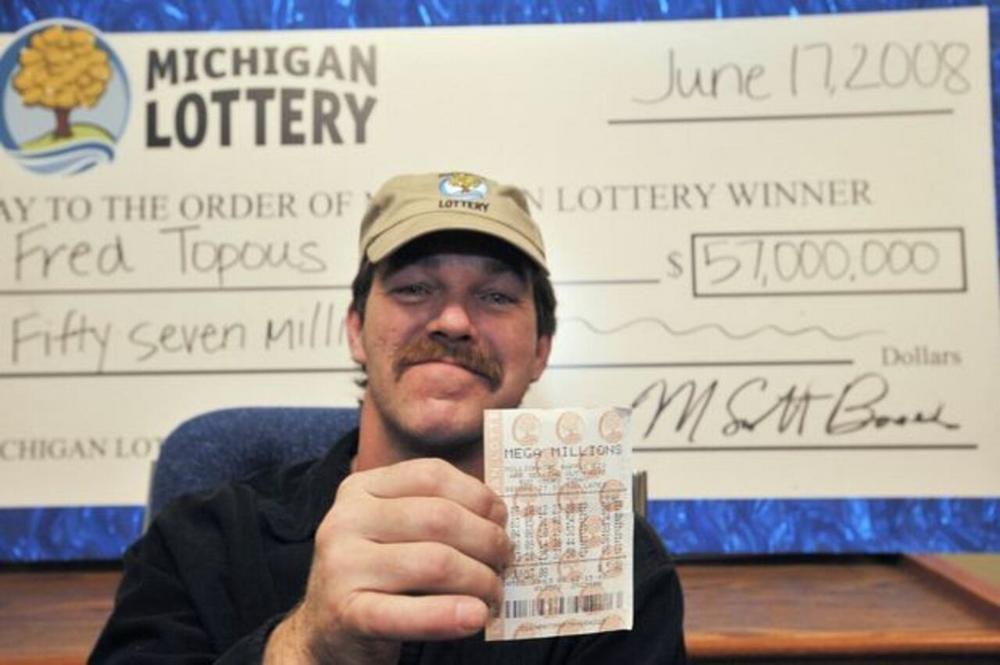

But no, success is “lucky.” A successful business is a lottery ticket.

It’s dismissive, even insulting: It wasn’t you, it was luck. Your decisions weren’t important, your ideas weren’t special, the long hours didn’t matter—you’re just lucky. Anyone in your place would have done the same; time and chance happeneth to them all.

It’s easy to reflect back that dismissive indignation:

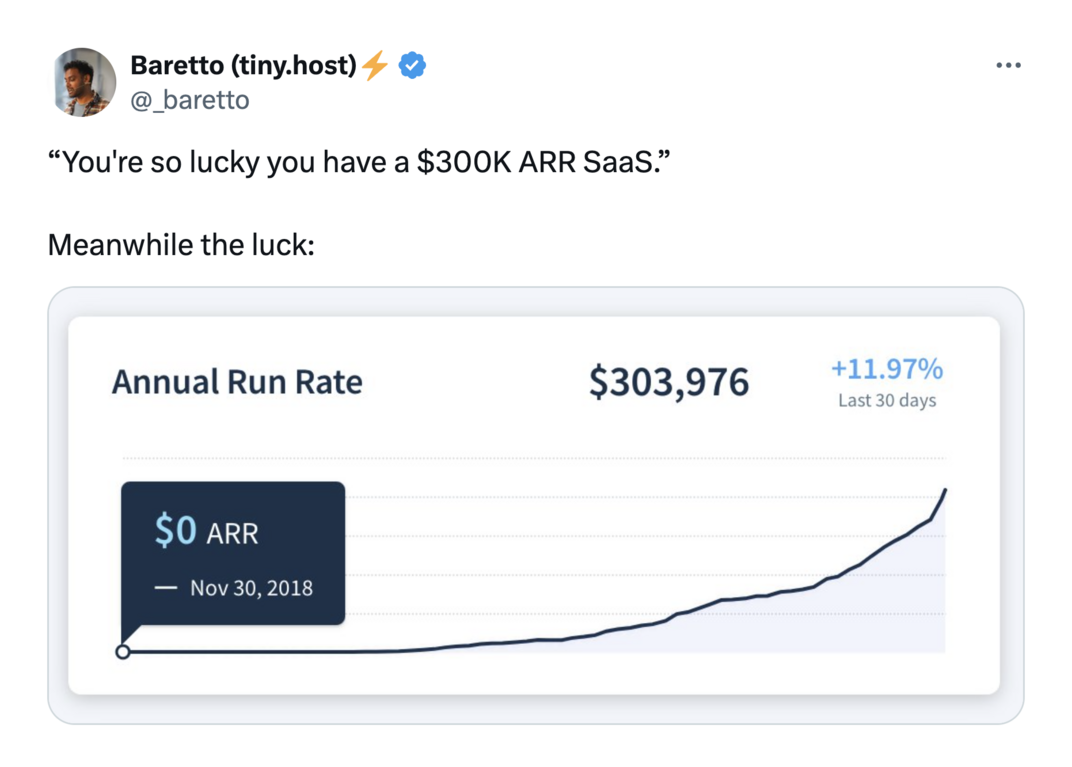

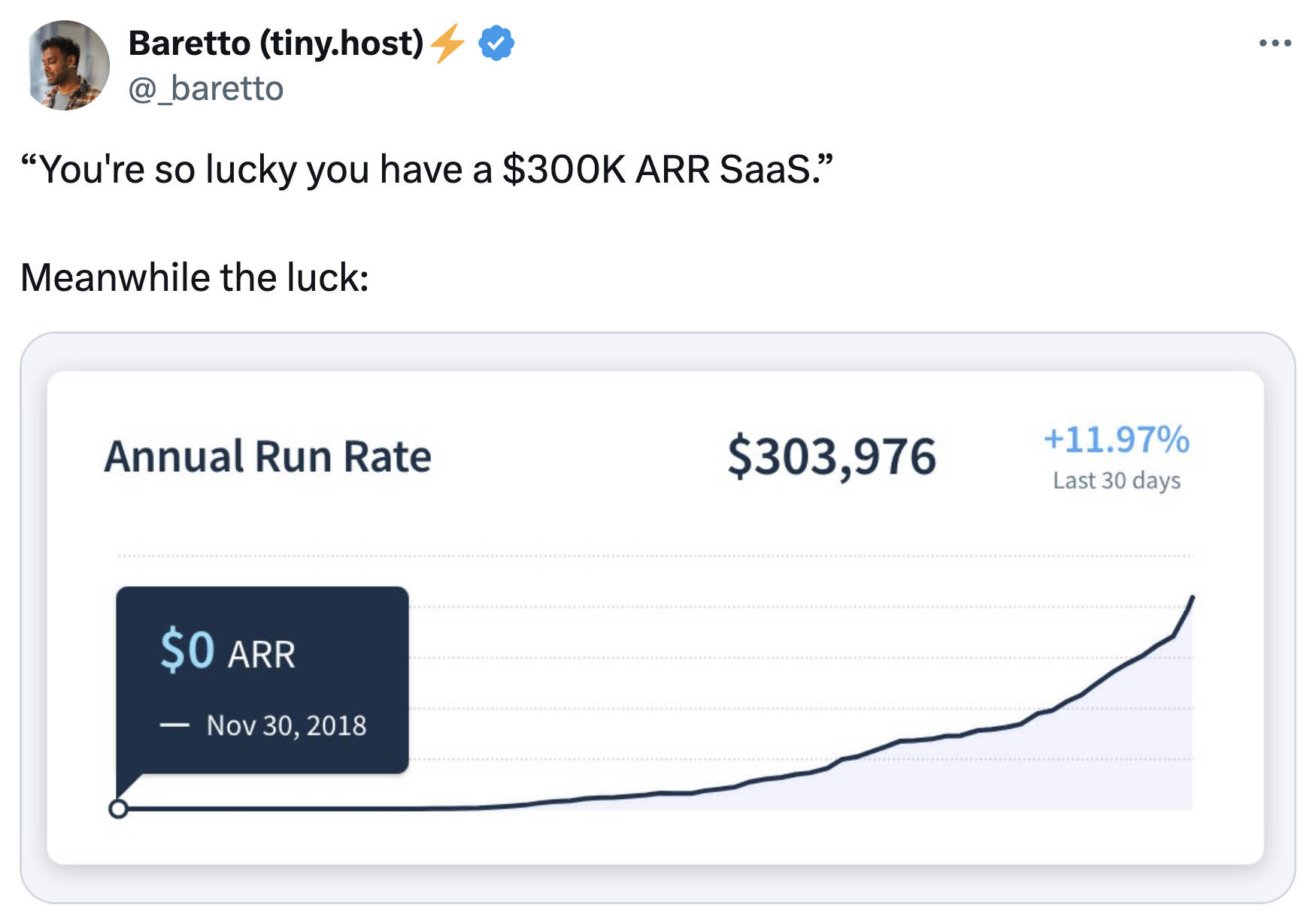

So when I quit my job and worked 60 hours a week with no pay for years, sacrificing my health, and finally clawed my way out, that was luck?

So when I invented a unique product and built it from scratch in a market that didn’t even exist yet, and people not only needed it but wanted it, and genuinely wanted to support us, that was luck?

So when I cultivated relationships with the best customers and truly listened to their needs using a specific framework, that was luck?

So when I had the chance to sell my company at a fair price and negotiated a deal that put more money in the pockets of my employees than any other job would have, that was luck?

These retorts are fair. But both things can be true. These demonstrate that it’s not only luck—it is not identical to a lottery ticket—but isn’t there luck buoying up all aspects of the endeavor?

Yes I cultivated relationships with customers, but wasn’t it lucky that the customers showed up in the first place? Yes, they found me through my Google Ads, but wasn’t it lucky that I started Smart Bear right when AdWords were new and cheap, when everyone used Google but AdWords weren’t saturated with garbage? Yes, I chose effective, brief marketing messages with an authentic voice, but wasn’t it lucky that I had a mentor who had already taught me how to do that?1

In fact, I can pick any decision in the history of Smart Bear and the same rhetorical pattern appears: Success tied to something intentional,2 but also leveraging something lucky.

1 Update in 2024: I started WP Engine a year after writing this article; fourteen years after that, it’s been a unicorn for years, 100x larger than Smart Bear ever was. Once again, it was a great idea, great execution, an immense amount of effort from thousands of people over the years… but also luck: Lucky that the WordPress market in which we operate remained healthy and fast-growing throughout our journey, lucky that people in the WordPress community gave us the benefit of the doubt at first and supported us later, lucky that we were able to hire so many incredibly talented people, lucky that it took serious competitors ten years before they really understood how big our market is, and the list continues.

2 Just because it’s intentional, doesn’t mean everything worked on the first try. Indeed, almost nothing works on the first try. You have to experiment and fail before you find success; pushing through that is tenacity, but there’s luck in how quickly you find that success, or if you ever do, and if you can even tell the difference.

Besides this operational luck, there’s personal luck, which many people call “privilege” and which Warren Buffett calls “winning the genetic lottery”—the luck of being born in this era (not in the Middle Ages), in this country (the US in my case, easily the most supportive place to start a company), to this family (I had a stable household), with certain talents (e.g. building software, problem-solving, being tenacious, having focus), and with this ethnicity, gender, and with all body parts in good working order. While none of this negates the value or necessity of hard work and good choices, neither can you ignore these tailwinds in the final equation of “success.”

My conclusion:

Good luck and bad luck are constantly swirling around you.

How you use it, is not luck.

These individual successes are a result of taking advantage of good luck. What about failures?

At Smart Bear, lots of marketing and advertising attempts flopped. Ads in certain magazines bombed. (I’m withholding names; print media is having a tough time as it is.3) In some cases I spent many thousands of dollars—which at the time was a significant percentage of revenues—on ads that didn’t net a single sale.

3 Update in 2024: Every single magazine that I used to advertise in, has gone out of business.

Ads that utterly fail in one magazine when they worked in another—that’s bad luck. The choice to cancel some ads and not others is not luck. In fact, ensuring that we could measure the efficacy of individual print ads was also a choice. Had we not done this, we wouldn’t have been able to distinguish success from failure, and then indeed our destiny would be controlled by luck alone. There are lots of ways to “fail” without failure.

Overall success in business doesn’t only mean you “got lucky,” it means you used luck, taking advantage of the good, identifying and ejecting the bad.

“Luck” rarely comes up when I’m talking to other entrepreneurs. They’re interested in stories and tips and how things work. They want to know how to think, not how to copy. The wrong question is: “What inspired that idea?” The right question is: “How did you know when an idea was right?” Or even more specific: “How does one know whether a print ad is working?”

Your best bet for success is to treat all your decisions as empirical tests. Confidence and experimentation are not contradictory. Try anything, measure everything, and follow what works, even if that means changing everything.

Then maybe you can be lucky too.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/lucky/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF