Easy to criticize, hard to create

I can rip any business idea to shreds.

Take Netflix1: The costs of inventory logistics, millions of non-technical customers, the Postal Service, and loss from wear and delivery will make profit impossible if you keep retail prices reasonable. Movie-watchers are accustomed to the immediate gratification of browsing and selecting. People will duplicate movies, pissing off the publishers. Blockbuster will duplicate the model and undercut the price, combining the convenience of home delivery with the equally convenient option of store browsing and returns.

1 Editor’s Note: This was written in 2011, before Netflix pivoted to streaming.

Terrible idea that could never work. Except that now Blockbuster (who did copy it) is bankrupt and Netflix turned a profit of $60m last quarter, which is more than Blockbuster was doing at its peak.

I suppose if your goal in life is to be right, you should bet against every startup, certainly against any novel ideas. You’ll be right much more often than wrong.

Right, but useless. Right, but ensuring that nothing new or great will be created. We can even show mathematically why this is flawed, but you don’t need math to know that this isn’t a useful way to live.

The goal of the entrepreneur is not to be “right.” At least, not right about everything, all the time, from the very start.

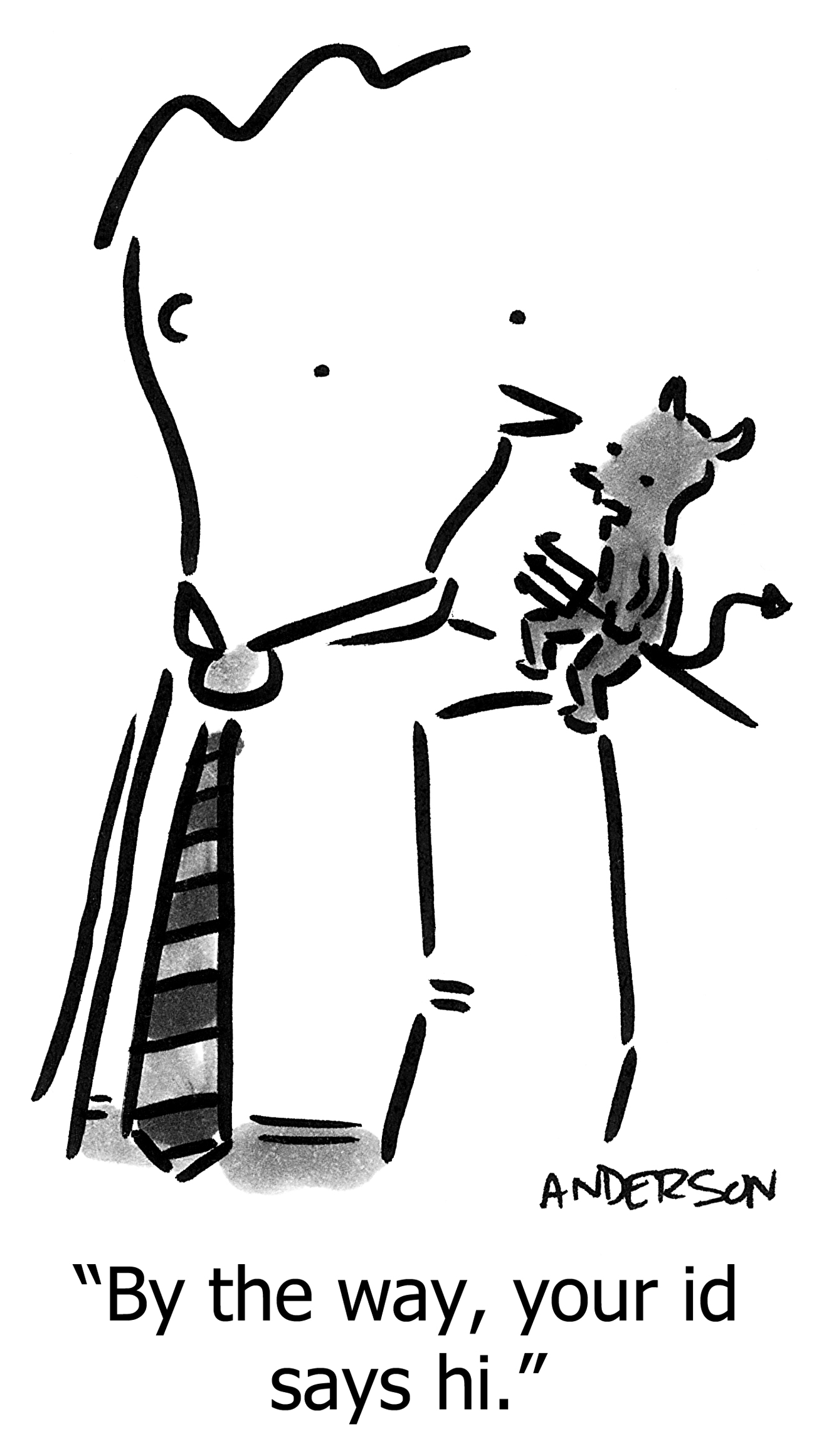

It’s to construct with humility. To have strong opinions but seek better ones. To infect customers and employees with your peculiar disease. To live to fight another day. To acknowledge being wrong before the fault turns fatal.

To realize that even if a particular venture is a “failure,” it never really is. I’ve never met a “failed” entrepreneur who doesn’t proudly declare they’re better off now: developed skills they never thought possible, learned what makes them excited to get up in the morning, came face-to-face with their fundamental limitations, and now more confident than ever in what they are capable of, regardless of the future shape of their career.

The Lean Startup movement2 also values learning and experience over “being right,” specifically casting this concept as “running experiments.” And the great Francis Crick (Nobel-winner for discovery of DNA) posthumously agrees with that analogy:

2 Editor’s Note: The Lean Startup book was published in the same year as this article.

The dangerous man is the one who has only one idea, because then he’ll fight and die for it. The way real science goes is that you come up with lots of ideas, and most of them will be wrong.

—Francis Crick

Real science is mostly being wrong, but staying vigilant and honest enough to continue being wrong until you’re not wrong. So it is with dating. Or startups.

The problem with armchair criticism is it’s so easy. Of course it’s easy.

Designers want to be “right,” but have to temper that with analytics. The true masters are those who embrace metrics as an incontrovertible goal while also being creative enough to retain the aesthetics, creativity, and philosophy which makes their craft an art.

Programmers want to be “right,” but have to temper that with getting things built and shipped, even before it’s ready, even with bugs, willing to build what customers actually want, and indeed features customers truly love instead of rationally calculated.

Backseat advisors and pundits (like me) want to be “right,” but have to temper that with the more important goal of inspiring people to be a better version of themselves instead of indoctrinating them with our own biases and experiences that contain unknown quantities of luck.

As a founder, you still need to listen to critics with half an ear. Sometimes you have been blind, and they’re showing you the truth. I resist opposition to my ideas, more than I know I should. I still hate being wrong.

But it has to be possible to be able negate you, otherwise you are certainly pig-headed. As the founder of WP Engine I feel that most days are filled with more contradictions than construction—balancing customer needs with internal costs, following our nose against what competitors are doing or saying versus staying true to our “vision” while also flexing as we learn what the market wants and even what we want for ourselves.

It’s easy to criticize but it’s just as easy for you to dismiss criticism without consideration. That’s equally hazardous.

Whenever you get the criticism ask: Does it sting exactly because there’s an element of truth that I don’t want to face?

Ignore the messenger, ignore the emotion, and see whether it’s a gift of truth, poorly wrapped.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/criticize-create/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear