The “Talk vs Walk” workshop

Despite the insipid rhyming, it’s a surprisingly useful question to analyze:

You talk the talk, but do you walk the walk?

Whether it’s the early-stage company, understandably exaggerating its product’s qualities on the home page in a lived experience of “Fake it ‘till you make it,”1 or the venerable company whose marketing department isn’t taking enough credit for legitimately world-class qualities, because they’ve become so second-nature that it doesn’t occur to them to brag about it.

1 Again with the rhyming?

Plotting items on a “talk” vs “walk” chart is not only useful in analyzing current-state, but also in uncovering ways that both the Marketing and Product groups can sell better and create better products.

The method

Write-storming ideas

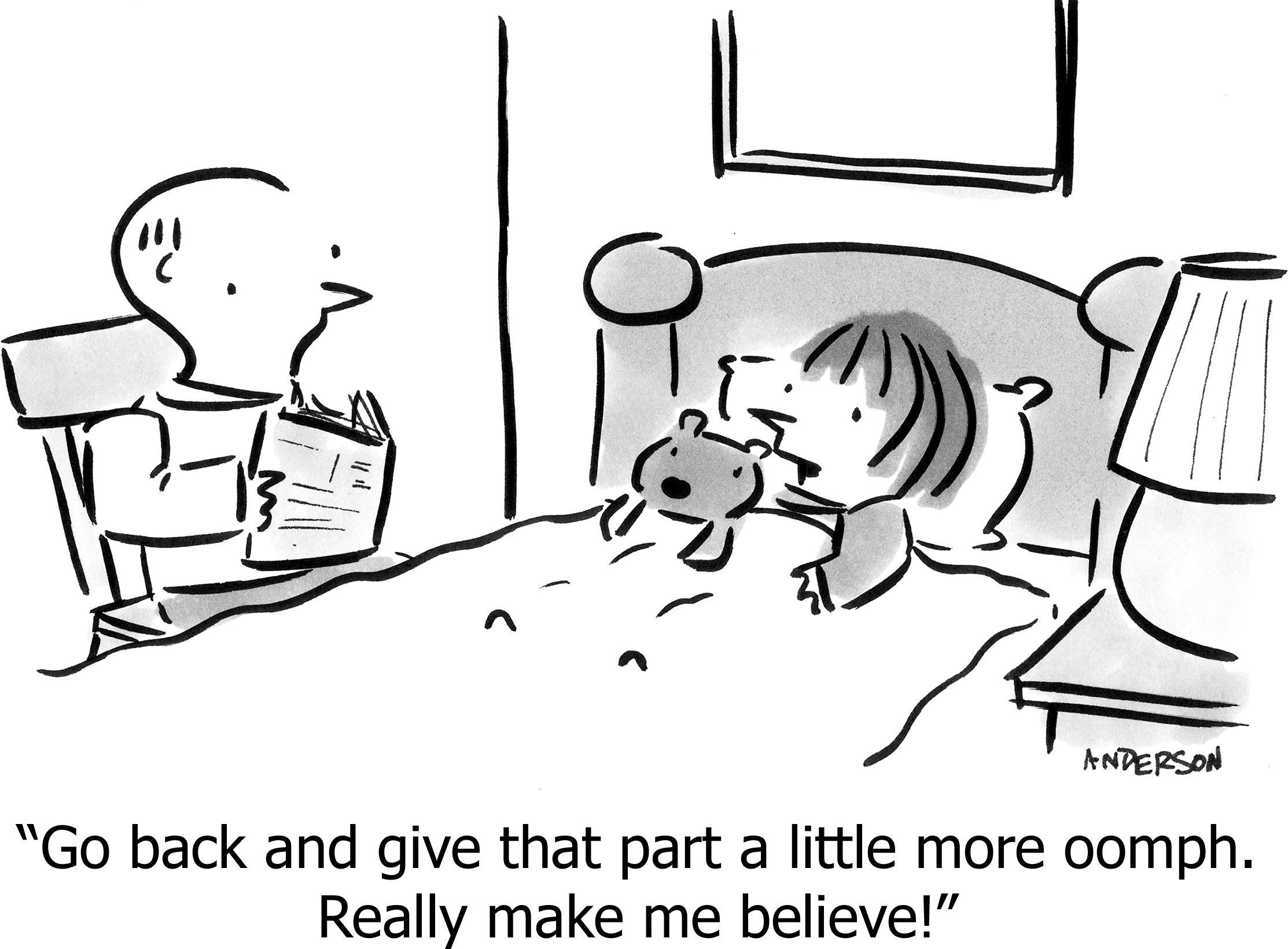

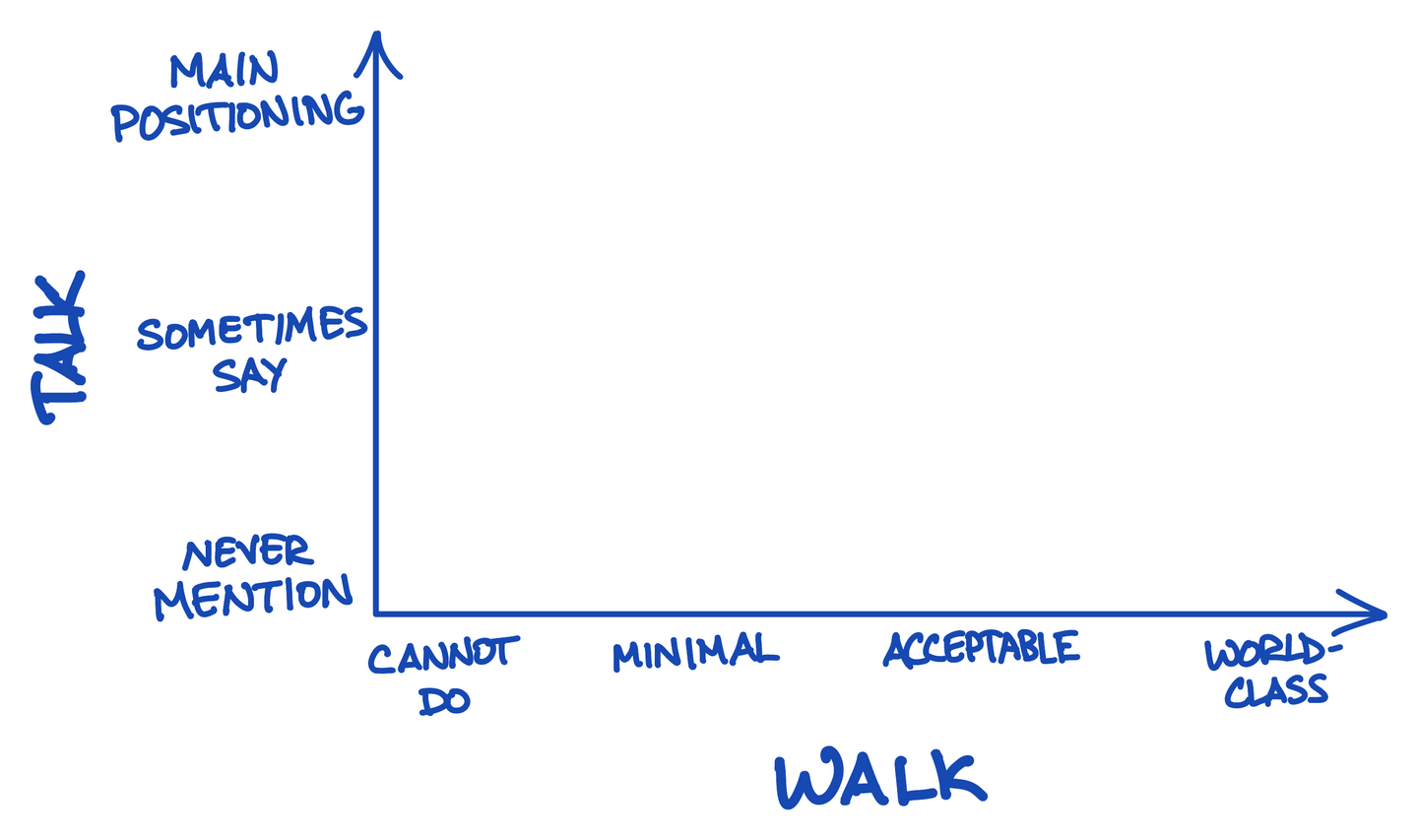

Using a whiteboard,2 set up a vertical axis called “Talk: How much/loudly do we claim this” and a horizontal axis called “Walk: How well do we pay this off in practice.” (Figure 1)

2 Likely virtual nowadays, e.g. Miro, LucidChart, or even Google Slides; something where folks can easily create and drag around “cards,” and see the results immediately.

Figure 1

Then, independently write-storm:3 Create “sticky notes” and place them wherever each person believes they should go on the chart. You could even allow several days, giving people time to think and to schedule the thinking during periods when their brains and work-environments are most effective at tackling such projects.

3 Do not brain-storm items one-by-one. In live brain-storming the conversations follows the fastest and loudest people, rather than leveraging everyone’s brains to invent different ideas. Live brainstorming filters out ideas that take longer than a few minutes to think of. Live brainstorming eliminates the possibility of having an “ah-ha” moment in the shower. “There is not a single published study in which a face-to-face brainstorming group outperforms a [write-storming] group” observes Leigh Thompson in Creative Conspiracy. Recent research suggests that people are less creative in generating ideas over video-conferencing versus in-person; write-storming restores the creativity because it’s independent, even if the discussion is over Zoom.

Where do ideas come from? Because the exercise is about “what our company claims,” obvious sources are the public website, advertisements, public presentations and webinars, quotes from your employees in the media, sales materials, and support materials like knowledge-base articles or copy/paste shortcuts. If you’re quoting directly, put the phrase in double-quotes to emphasize that “we really do say this!”

There are also the things you’re doing that you’re not talking about. Those things are more difficult to generate. Sources are what you’re maintaining (i.e. existing systems owned by some team), work from recent sprints (i.e. work you’re actually doing), long-term planning documents (i.e. larger initiatives), and prompts like “What are we really good at?” and “What technology assets or human capabilities have we built up over time?”

The hardest things to think of, are the things you’re not talking about and also not doing. Isn’t that an infinite number of things? Yes, but it’s useful to list things you reasonably could say or do, but are intentionally avoiding. One source is backlogs of features requests from customers, support, sales, marketing, product, and engineers; whether you plan to do them eventually or not, they are “items of interest.” Another source is key, differentiating things that competitors are saying or doing (whether you’re avoiding those things purposefully or reluctantly). Yet another is your own long-term plans for big initiatives you haven’t gotten to yet.

Debating placement is one-third the value

Come together as a group, take each idea in turn, and debate where it should go on the chart. Coalesce duplicates into a single card; if the duplicates were originally strewn all over the chart, that’s even more indication that a discussion is useful. If there’s immediate widespread agreement on the right location for a card, skip the discussion to save time.

Generally you’ll find three sources of disagreements. All three are useful, but in different ways:

- Lack of knowledge

- “We don’t talk about this.” “Yes we do, it’s in all the sales materials!” “In support, we tell people the opposite.” “We say this in sales but not on the website.” “We used to say that, but not since the latest website revamp.”

This is a great excuse to get everyone up to speed about what we’re saying, and where. If the answer varies (e.g. “we say this a lot on the home page, but nowhere else”), you can place the item more in the middle of the chart, but add a “comment” to record that detail; it will be useful later when you decide how to act on this information. - Disagreement on terminology

- People often interpret the same phrase differently. If you can’t agree on what it means internally, imagine how confused customers are! Or a new employee who isn’t part of the echo chamber?

An example will illustrate how this is useful: In a recent exercise at WP Engine, multiple people put “Enterprise-Grade Security” on the board. We talk about this constantly, so no one disagreed that it was high on the “talk” axis. But there was disagreement on “walk,” ranging from the middle to the far-right.

But how is this controversial? We’re well-known for having the best security in the industry. Our customers include some of the largest security companies and financial institutions in the world, both of which maintain the highest bar for security; we are certified with multiple accreditations; we leverage myriad security products covering every layer of the tech stack; we commission third-party pen-tests for every new product and periodically for all products; we conduct annual company-wide training to guard against social engineering attacks; we have formal written security policies that we actually enforce. With all this, how could you not agree “Security” is 100% on “walking the walk?”

Turned out, the person who placed it in the middle was specifically thinking about a few items in the backlog that would make a certain corner the platform even more secure. We’d never experienced an incident because of, and there was no reason to believe we would. Still, this person thought, If there’s still a few obvious items in the backlog that we could do, then we’re not yet fully “walking the walk” on security.

A discussion resolved the difference of opinion. We decided that “great security” isn’t defined by never having a ticket in the backlog; after all, nearly all software updates contains security patches (check the version history!). That doesn’t mean the software wasn’t already secure. Indeed, it’s the opposite: Being so diligent that we even “fix” things that aren’t broken, thinking a few steps ahead, proactively preventing incidents, is what makes us secure; it’s a sign that we are in fact “walking the walk.”

The group finally agreed that the ticket belongs on the far right side. The realization, however, was helpful both for the engineers who have a better mental model of “what security means,” and for the marketers who have more stories to tell about how excellent our security is. - Disagreement on target persona

- Sometimes you realize that a subset of your customers would agree that you’re “walking the walk,” but others would disagree.

For example, perhaps the performance of your product is excellent for most customers, so when you say “fast user interface that never gets in your way,” most people would agree. But maybe 2% of your customers have huge amount of data that slows your UI to a crawl. Furthermore, that 2% are important to you—they might be your reference customers, or the ones paying you the most money.

What do you do in these fractured circumstances? A simple technique is to place the item in a sort of “weighted” location. So e.g. if 80% of your customers (by revenue) would consider this completely “walking the walk,” but 20% would say it’s pretty low, perhaps you place the item at 80%. However, add a comment to the sticky-note explaining this detail; it will be useful later when you decide what actions you want to take.

Another technique is to split the item. So e.g. “Fast UI (for customers <100 properties)” and also “Fast UI (for customers with ≥100 properties).” Then place them independently.

If you have different, distinct target personas, you might find a lot of the cards are being split. In this case, consider making two different charts altogether, i.e. one for “Talk vs Walk for Persona A” and the other “Talk vs Walk for Persona B.” This is easier to read and to act on.

Taking action

Just having these discussions is valuable, but most of the value is in doing something with the resulting chart.

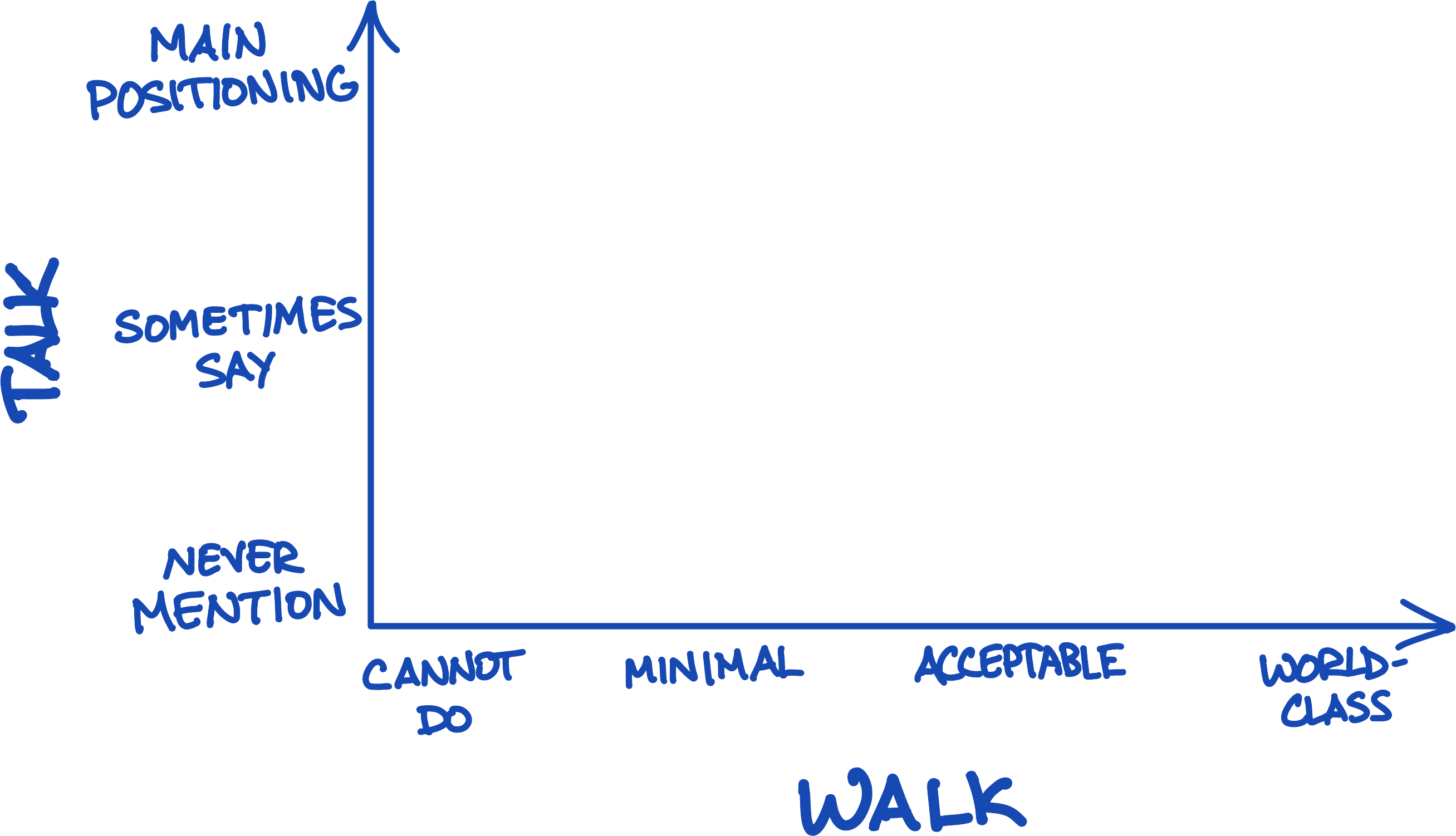

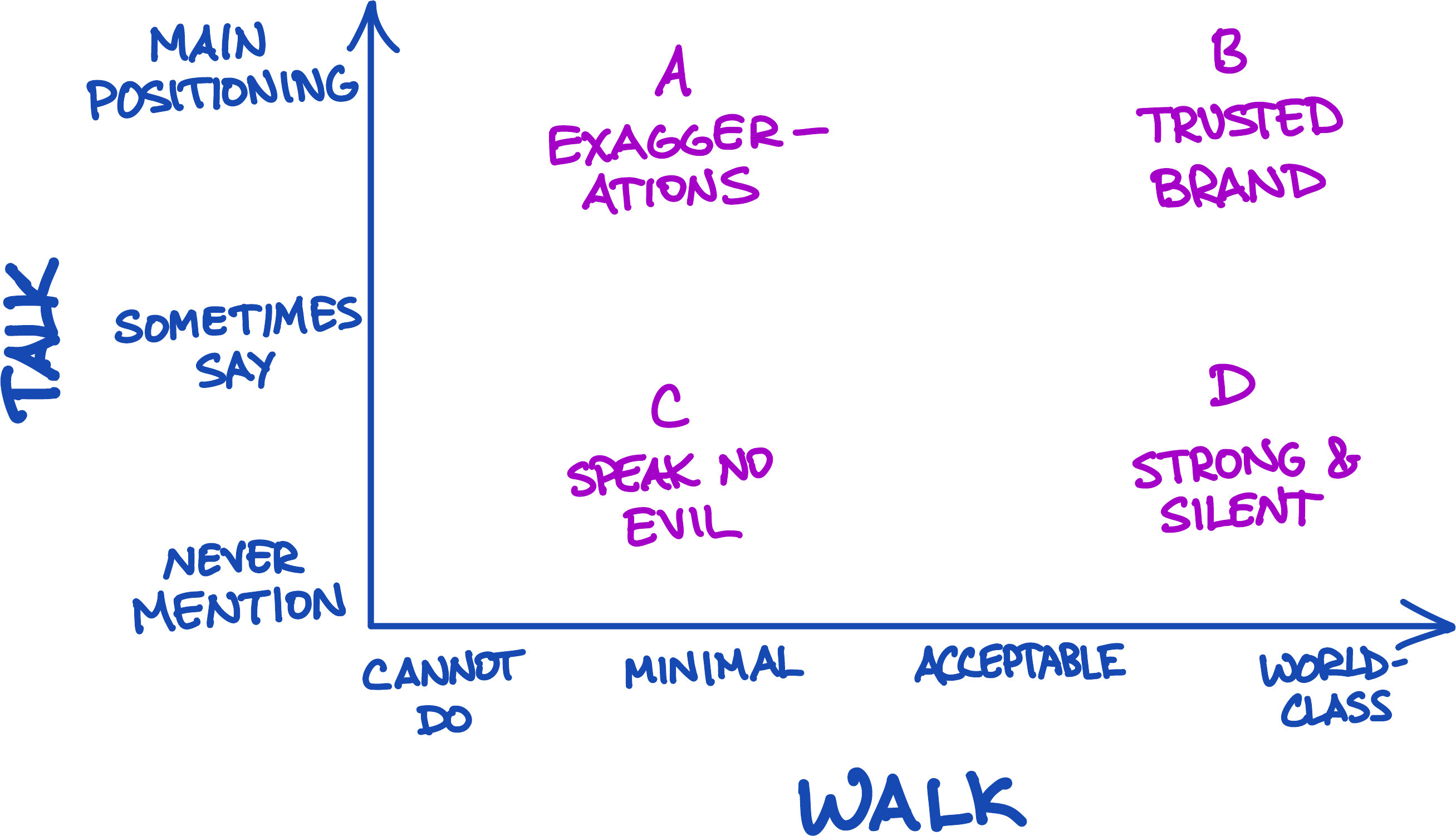

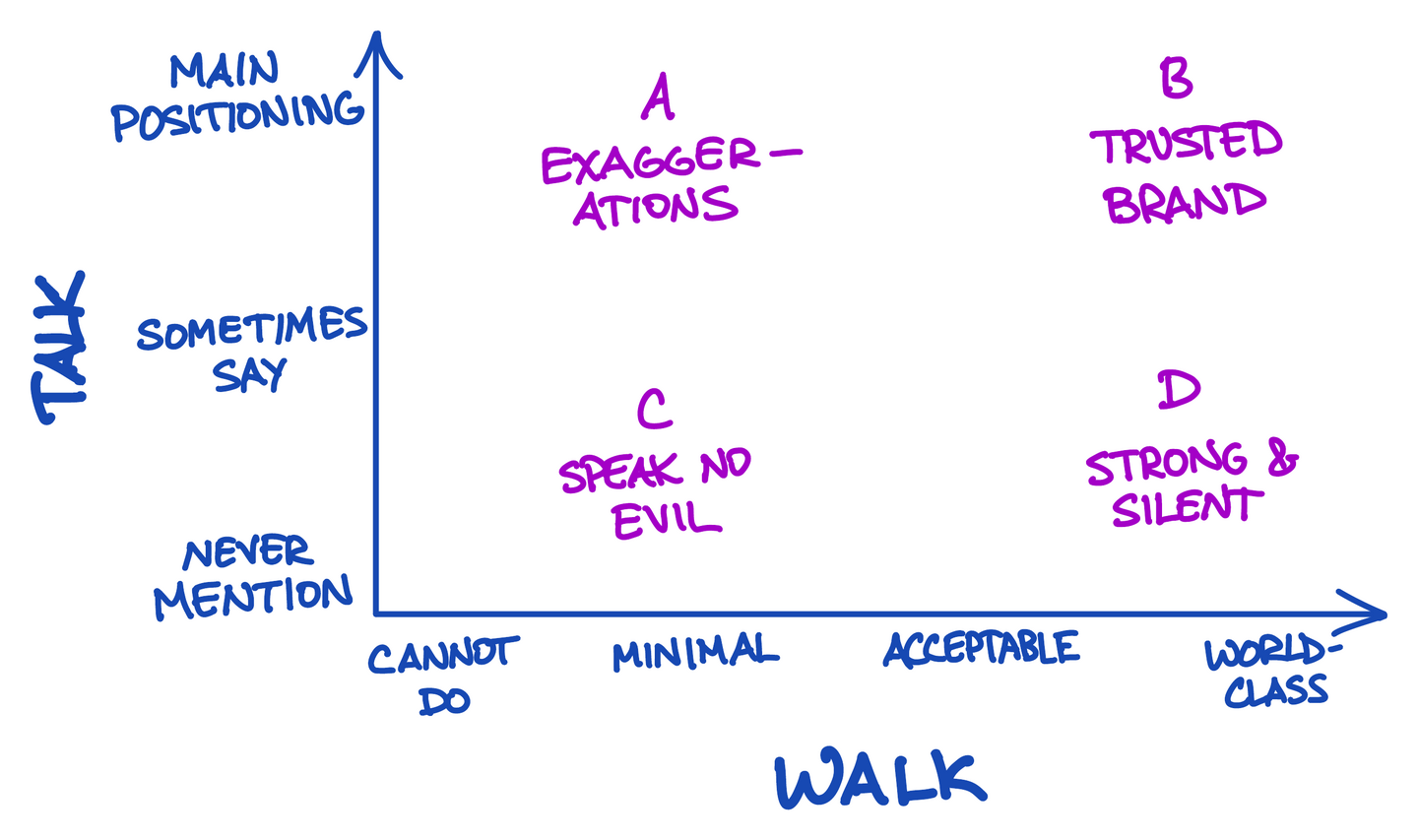

In general the question is: Is it useful to take action to shift cards in various directions? It’s useful to consider this by quadrant (Figure 2), because those items have different status quo interpretations.

Figure 2

Quadrant A: Exaggerations

These are the original source of the line “you talk the talk but you don’t walk the walk.” When you’re “faking it ‘till you make it,” but still just faking it. What to do?

- Do nothing (ethically)

- We understand our claims are tenuous. We should ensure that our exaggeration is not unethical, e.g. claiming a medical benefit that does not exist, or charging for a feature that does not work.

- Live up to your own expectations (shift →)

- This message is resonating, and is a critical to our positioning. But if it’s so critical, we have to back it up with reality! We’ll build and ship specific things in the next six months that will allow us to shift these sticky-notes rightward to meet our customers’ expectations.

- Don’t write checks you can’t cash (shift ↓)

- We’re attracting the wrong sort of customers—people who expect something we don’t deliver. As a result they waste time in customer service and then cancel anyway—a net loss for us, and a terrible experience for them. We’re not even getting useful product feedback, because we’re interviewing people who aren’t our target persona. Let’s stop saying these things.

Quadrant B: The trusted brand

Trust is earned by repeatedly keeping your promises; that’s what’s happening in this quadrant. This is your brand, because it’s what you say and also what customers actually experience. This is a strength, because everything is constructively aligned. What to do?

- Do nothing

- We’re doing well here, but doing incrementally better will not win us more customers (i.e. Kano “must-be” or “indifferent”). Therefore, we should track our performance on this item as a KPI, but rather than continue investing to maximize it, we should only promise that it won’t fall below some minimum threshold of acceptability. This ensures we won’t unintentionally lose this advantage. Instead, focus our attention on accumulating more strengths, or mitigating some issue.

- Leverage strength for sales (shift ↑)

- Can we make even more fuss about how awesome we are? More confident competitive positioning, leveraged in advertising, more content marketing on the subject, emphasized more in sales processes, highlighted more in the product UI. We might even be able to make sales by emphasizing one strength above all others.

- Double-down on strength (shift →)

- It’s often wise to invest more in what’s already working, especially early in a product’s life when it’s hard to have even one thing that is special, or a reason to buy despite its many deficiencies. This only works when customers value the additional investment (i.e. Kano “attractive” or “performance”), but if that’s the case, it might be the most strategic thing you can do.

- Pivot (shift ↓)

- While it’s unusual to jettison a strength, it makes sense if the company is pivoting: Changing its target, or how its brand and product is positioned against the competition.

Quadrant C: Speak no evil

Often there’s not much in this quadrant, because it’s easier to think of things you’re saying and doing, and these are neither. However, it’s valuable to list “things we know are weaknesses” or “things we’re saying ‘no’ to,” especially if it’s a common topic of conversation at the office, or if a competitor is successfully talking and walking that item.

- Do nothing

- This is the correct answer for nearly everything here. It’s expensive and high-risk to turn a weakness into a strength; your energy is probably better spend executing on your current promises and doubling-down on strengths.

- Turn it around (shift →)

- If this is truly a key area that is critical to succeed in the market—which is another way of saying “strategic”—then this is a weakness to highlight, and to invest in. Should you shift it up (start talking publicly) before you’ve shifted it right (pay off the claims)? Probably not: You tip your hand to competitors, allowing them to react before you can defend. You also set incorrect expectations for customers; later when you really can pay off your words, you’ve already trained them to disbelieve you. Conversely, talking first can freeze the market,4 but only if your market leadership position is so strong that a press release actually does change market behavior. Unlikely.

4 “The U.S. District Court … suggested barring Microsoft from making vaporware announcements because doing so can allegedly freeze the market and discourage buyers from purchasing competing products. … ‘I feel very sure there have been many times when Microsoft has announced products to freeze the market, [but] lots of companies have done that,’ Kertzman said.”— Computer World, 1995

Quadrant D: The strong, silent type

If you are excellent, why not get credit for it?

- Do nothing

- There might be a good reason for not making a fuss. It could be a trade secret that you don’t want competitors knowing about (but you could brag that a trade secret is part of the magic that makes you different). It could be “boring” internal operational stuff (but customers might be comforted knowing that you’re operationally advanced, and a tech blog is a recruiting tool).

- Talk about it (shift ↑)

- Even if this is a secondary or tertiary message, it’s nice to arm sales with more material, or test it in advertising, or make a landing page for the subset of customers who would be impressed.

Application to competitive strategy

Turn the tables on your competition to reveal more insights.

Adding the competition to both charts

Build the Talk/Walk chart for a competitor.

Place a copy of your cards onto their board. There might be a lot in quadrant C (“Speak no Evil”).

Then create the new cards that makes sense for them. These prompts help generate ideas:

- What do they emphasize (big or bold font) on their home page, “pricing” page, and “about us” page?

- What main features do they highlight on their “features” page?

- On what points do you lose to them in sales? Which are they legitimately great at, versus which are they just really good at selling?

- On what points do you beat them in sales? For which do they deserve it, versus which are you just good at claiming?

- What do their customers say about them (e.g. on Twitter or testimonials)?

- What do your customers say about them (e.g. when complaining or asking for features, do they reference the competition?)

- If you were making an investor pitch on their behalf, what would you say? How much of that would be true, versus aspirational?

- What cultural or moral principles do they or their founder or their CEO publicly espouse?

Whatever new cards you add to their chart, also add to your own chart, even if it mostly creates a pile in quadrant C. This is where it gets interesting.

Analyzing the competitor’s strengths

It’s especially instructive to compare your competitor’s strengths to everything on your board. Place their strengths onto your board in a unique color, i.e. evaluating whether you also talk about those things or not, or you also do those things or not. Every quadrant is actionable:

- Quadrant A: Exaggerating against their strength

- You’re both making a claim, but only your competitor is fulfilling that promise. Over time this erodes your brand; potential customers start dismissing you, saying “Yeah, everyone claims to have X, but only P really does X.” You were already claiming something ahead of having it, and now the competitor is exposing your little fibs.

Before you decide to knuckle down and match the competitor strength-for-strength, critically consider whether you want to run a race where you’re starting out behind. Do you have what it takes in long-term will-power, and investment in time and skill, not only to catch up to where they are today, but to where they will be in another year? Will the result of that expensive and risky activity pay off enough to be worth it? Occasionally the answer is “yes,” but usually the answer should be “no, let’s move this card downward—stop making this claim—and instead focus on increasing our differentiating advantages in Quadrant B, where we are the ones in the lead.” - Quadrant B: Table-stakes; find the differentiation

- You’re both doing well here. Perhaps these topics are considered “table-stakes” for any competitor in the market. That’s not a problem, but neither is it an advantage for you. Table-stakes are important to maintain, but it’s a mistake to over-invest in them at the expense of things that differentiate you, or at the expense of the few key weaknesses that you’re converting into strengths.

Your comparative advantages are the cards in this quadrant that aren’t shared with the competitor. Do you have a significant set of those cards? If not, inventing some might be the single most strategic thing you could do. - Quadrant C: It’s not your thing, and that’s OK

- This is where your competitor is differentiated against you. It’s easy to get discouraged or think this is a problem; it’s not. The only problem is if you don’t have your own unique strengths. If you both have your own strengths, that’s just defines your respective niches, which is useful to recognize.

As with Quadrant A, it’s highly unlikely that you should attempt to “turn it around” and become strong where your competitor is already strong. But, if there’s one item that’s truly important to win, you could set that intention. Just know that you can’t have more than one or two of those at a time, and often you’ll only get to mediocre, not a strength. It surely must be treated as a Rock. - Quadrant D: Don’t give them a free pass

- You’re letting your competitor take all the credit, even though you’re just as good. Change that! Sure, you’ll probably just match them, not create a new differentiated advantage, but since you’ve already done the work to be excellent in this area, don’t give them an uncontested win in sales calls.

I hope this exercise is as useful to you as it has been for us!

https://longform.asmartbear.com/talk-vs-walk/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF