Specificity: A weapon of mass effectiveness

My single best advice about writing—whether for marketing copy, blogging, a sales pitch, an investor pitch, or even humor, is:

BE SPECIFIC

All done, you can stop reading now. (Because I have the power to decide when you stop reading?)

Writer’s Workshop

It’s clearer to demonstrate than to preach, so let’s take a simple statement and see how being specific makes it more powerful, more interesting, and even more funny.

Here’s our starting point:

Experts say Twitter usage is increasing, but in many industries your marketing efforts are better spent in other channels.

No generic words

The first and easiest step is to swap generic words for specific ones. By “generic” I mean words that span broad concepts instead of conjuring a specific image. In our example, these include:

- usage

- many

- effort

- better

Generic words are a sure sign of lazy writing. You can’t be bothered to describe what people are doing on Twitter so you say “usage.” You can’t quantify the number of industries so you say “many.”

Besides being boring and uninspiring, generic words are interpreted differently by different people, so it’s not clear what message will be received on the other end of the internet connection.

Here’s a stab at converting generics into specifics; see how much clearer the point becomes:

Experts say people increasingly make buying decisions based on Twitter conversations, but in non-technical industries Twitter penetration is still low, so other marketing channels have a higher return on your time investment.

From truth to accuracy

After disposing with the obviously-useless generic words we’re still left with words which, while technically correct, are still not contributing enough to the meaning and persuasiveness of your writing.

Take the word “expert.” Yes “experts” talk about Twitter, but what sort of expert? When I think of Twitter experts I think of Chris Brogan and Tony Hsieh. But they’re not merely “experts” in the sense that they have a deep knowledge of Twitter, they also actively promote Twitter and teach others how to become experts themselves.

This is an important distinction, because experts in other fields are often not evangelical; an expert classical guitarist might not, in fact, be a teacher or care about convincing millions of people to pick up a 12-string, and few of the thousands of physicists at CERN have YouTube channels to teach concepts to high-schoolers.

In our workshopped example we’re making the point that Twitter experts tend to promote Twitter without qualification; using the word “evangelist” instead of “expert” is more specifically what we mean to say.

Replacing “expert” and a few other words (e.g. “higher return” → “profitable” and “people” → “consumers”), see how much more evocative the statement becomes:

Twitter evangelists insist that consumers make buying decisions based on Twitter conversations. But Twitter hasn’t made inroads in non-technical industries, so traditional marketing channels might be more profitable.

Concrete examples

If your primary goal is brevity, examples are bloat. Otherwise, examples improve persuasive writing in several ways:

- Examples clarify abstract arguments.

- Examples make arguments more believable.

- Examples make arguments more difficult to counter.

- Examples make it easier for readers to apply your points.

- Examples make it easier for readers to do their own research.

Consider how much more abstract this article would be without the workshopped sentence! Speaking of which, let’s update our Twitter statement:

Evangelists like Chris Brogan and Mike Volpe insist that consumers make buying decisions based on Twitter conversations. But Twitter hasn’t made inroads in non-technical industries like agriculture, construction, and retail, so in those cases it’s more profitable to stick with traditional marketing channels like direct mail and resellers.

See how much more evocative it is to put a name to the evangelists; even if you’ve never heard of those guys, knowing their names makes it tangible.

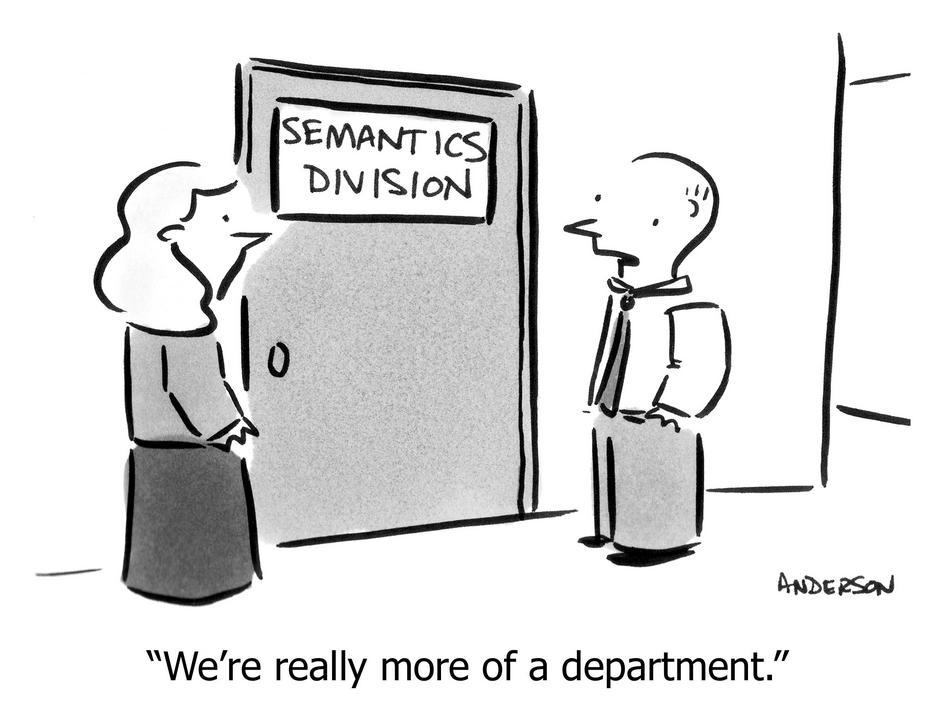

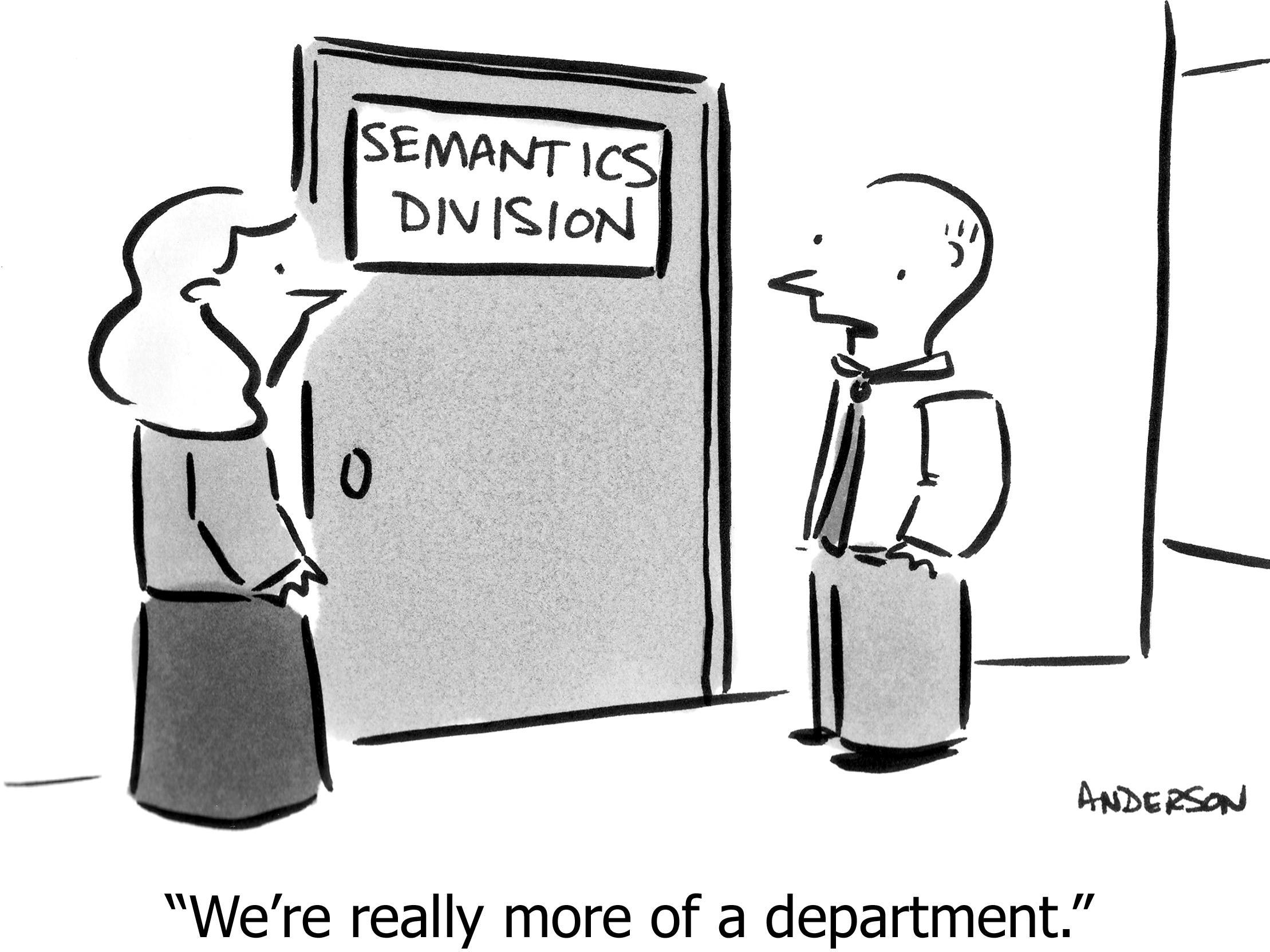

The easiest way to be funny

It’s odd but true that almost any statement can be made funny merely by being specific, and there are many ways to do it.

In the following examples, note how the individual nouns, verbs, and adjectives are specific.

- Exaggerate to extreme

- Instead of: “Evangelists enjoy pointing out how consumers use Twitter.”

Write: “Evangelists wet their pants every time someone uses Twitter to find a coffee shop.” - Exaggerate to banality

- Instead of: “Evangelists enjoy pointing out how consumers use Twitter.”

Write: “Evangelists proudly point to Twitter’s popularity, enabling people of every creed, color, persuasion and nationality to join the global conversation on what they had for lunch.” - Invent an example

- Instead of: “… hasn’t made inroads in non-technical industries.”

Write: “Farmers looking for a deal on a new tractor aren’t peeling iPhones out of their Wranglers and thumbing out tweets through work gloves.” - Highlight the absurd thing

- Instead of: “Evangelists enjoy pointing out how consumers use Twitter.”

Write: “Evangelists tells us we can use Twitter to gather ‘advice’ culled from the stray comments of millions of strangers and bots.” - Blow something out of proportion

- Instead of: “Evangelists enjoy pointing out how customers use Twitter.”

Write: “Evangelists say your customers are on Twitter, but mostly they’re twittering about how to twitter, and about how everyone else is twittering, and most of those people are bots, and about how all those human non-twitters are missing out on this incredible exchange of knowledge.” - Transfer the concept to another context

- This is the principle behind my satirical post on the “rules” of social media. (In fact that post demonstrates all these techniques!)

Putting it all together

Here’s some lovely examples of other writers using the above techniques for humor and effectiveness:

- Specificity and the Art of Being Wrong (Naomi Dunford)

- Painless Functional Specs—Part 4 (Joel Spolsky)

- Don’t Follow your Passion (Amy Hoy)

https://longform.asmartbear.com/specificity/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF