Limiting Options

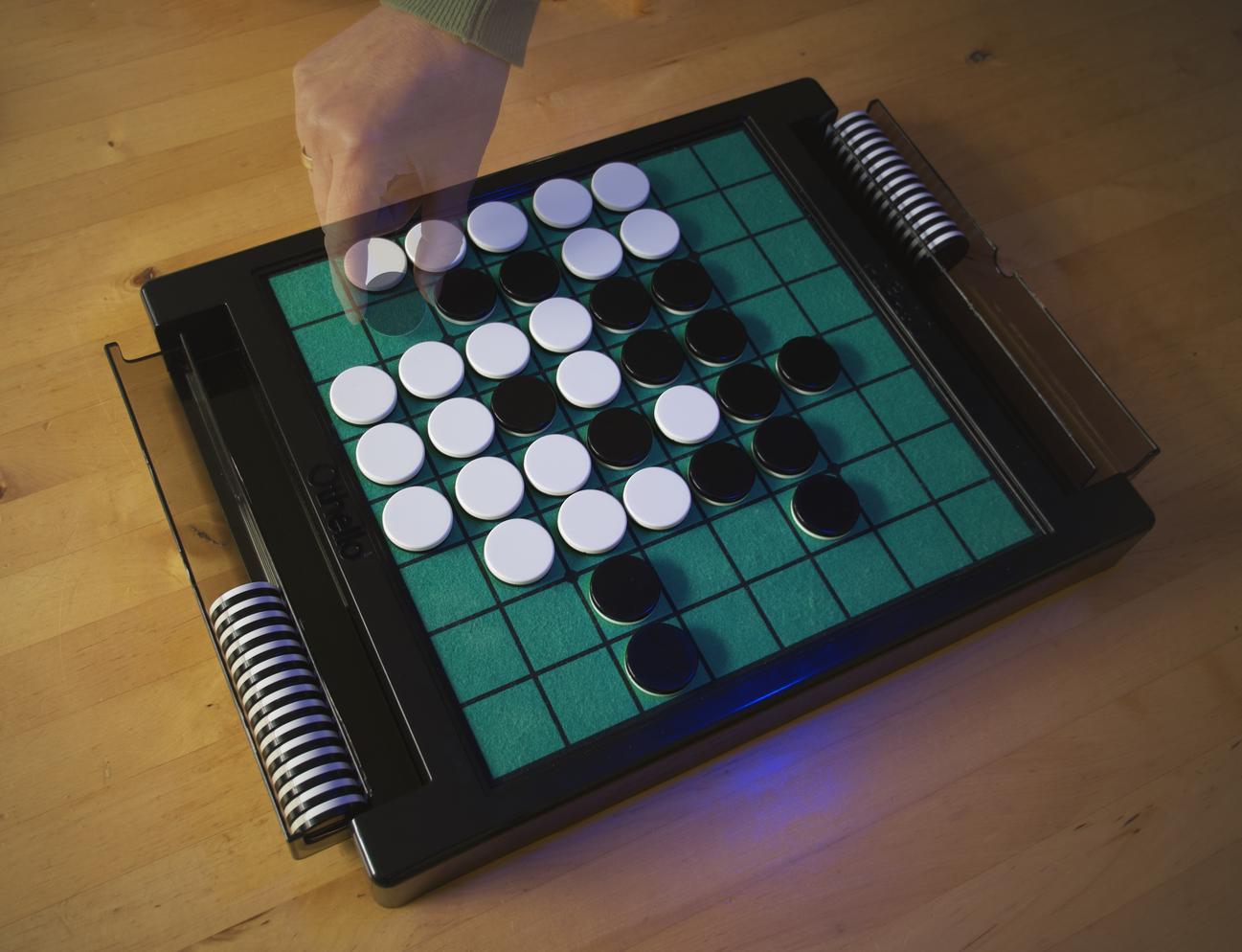

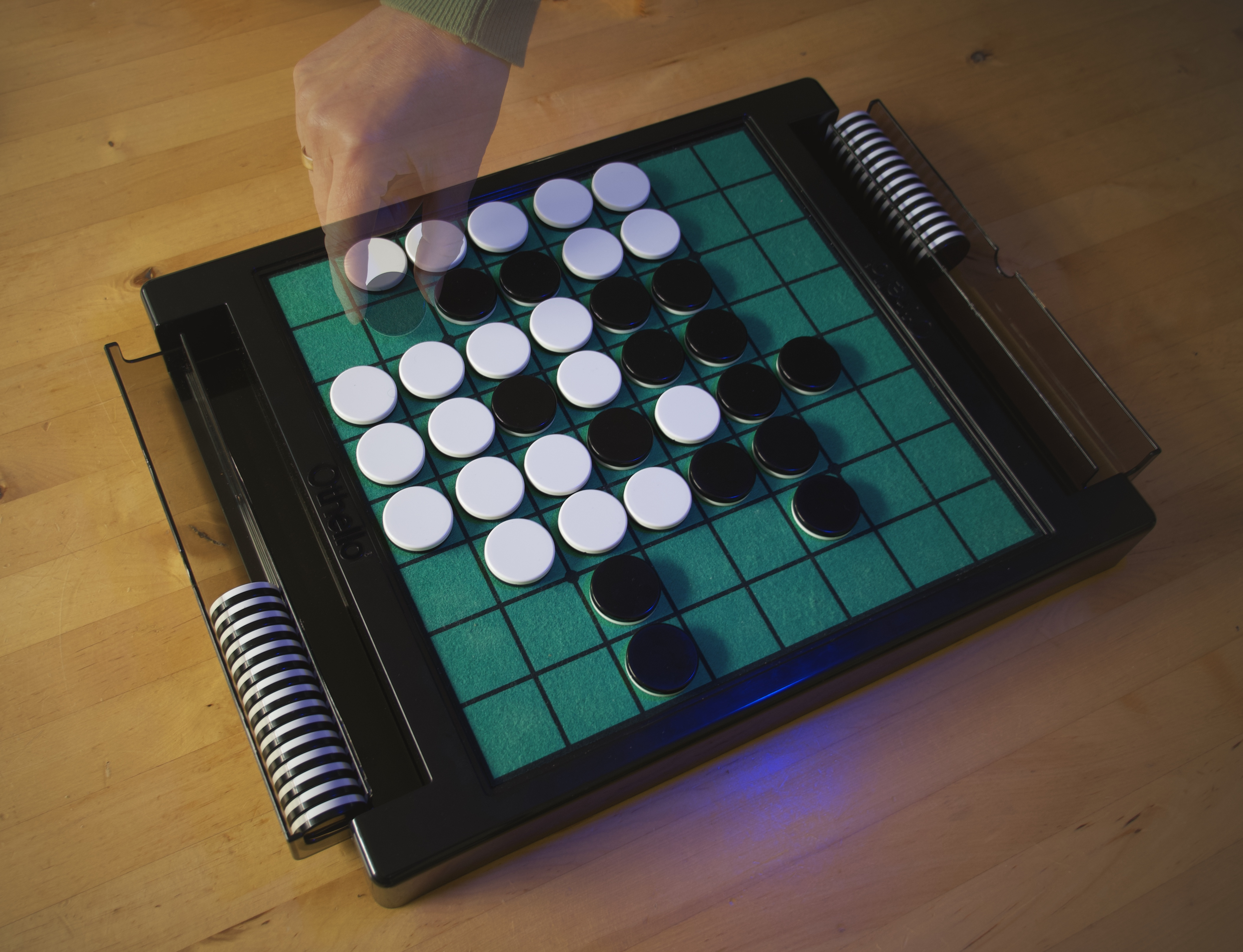

The 1990s was the golden age of computer AI’s for the board game Othello. (If there ever was a golden age…)

Programmers love the idea of computers beating humans at “intellectual games.” For me, it’s the “mad inventor” idea of creating something more intelligent than myself (whatever that means).

At the time, Checkers had been solved and Chess was close. It was Othello’s turn to fall.

What’s interesting is how the winning strategy worked.

The typical computer board game strategy is: Look many moves ahead and rate each resulting board position. Then pick the move that maximizes the ultimate board position you can achieve, even if the other player makes the best-possible move every time. The trick is in rating the “goodness” of a particular board position.

In Othello you win once there are no more legal moves, and if you have more tiles of your color than your opponent does. Therefore, typical metrics for “goodness” of Othello boards included things like “How many tiles of my own color do I have” (more is better), and “Tiles of my color at the edge of the board are more valuable than in the middle” (the edge is a better strategic position).

What’s neat is that the winning strategy used a completely different “goodness” metric. Specifically the metric was: How many valid moves does my opponent have? Fewer is better.

The flip was that it’s not primarily about how many tiles you have or even the positions of your pieces. Instead it’s about limiting how many choices your opponent has. Limiting choice is more important than what the choices are.

This principle is common in defensive theories of sports. The defense can never cover all contingencies so instead it forces the offense into higher-risk, lower-percentage moves. In basketball you can’t simultaneously cover the long shot and the charge, so you elect to give up the low-percentage three-point shot. In football you can’t cover both in-routes and out-routes, so you force a throw into as much traffic as possible.

In business your competitors always have options. How can you limit their choices to things that are low-percentage or expensive? Make them have to spend more money, get more lucky, or be more creative.

Here’s some:

- Honor the competitor’s coupons

- This eliminates the coupon as a way for your competitor to “beat” you; coupons are no longer a “choice” to develop a competitive edge.

- Overpay for the best advertising slots

- You are paying too much if you measure the direct ROI only, but there’s also the value of forcing competitors into a low-converting ad position, leading to many fewer customers at any price.

- Pay for exclusive deals with the largest affiliates

- You are (again) paying too much if you measure the direct ROI only, but you force competitors to work with affiliates who can generate only 1/10th the leads.

- Exclusive deals with brand-name suppliers

- Often your suppliers are invisible to your customers, but sometimes their identity is known, either because it cannot be helped or it’s part of your value-proposition that you’re integrated with a well-known brand. If that integration is something customers value, and you can make it exclusive, then your competitors have to find other, less-desirable ways to achieve the same thing, or else completely cede that capability to you.

- Patents (but…)

- Patents limit how a competitor can compete. If no one else can use your method, they’ll have to think of another way. But note: This is useless in software, where it’s always easy to do it another way. Software companies don’t protect themselves from competitors with patents; fortunately dozens of moats are potentially available.

We’ve done a few things at Smart Bear to limit options. For example, we’re so strongly established as “the experts in code review,” it would take an expensive, time-consuming effort for someone else to claim par, much less surpass what we’ve done. We literally wrote the book, we did the largest-ever study on code review, we have years of history, we have the most popular tool. It’s possible, but very hard, for someone else to compete on that particular basis.

This matters because in my opinion, being “the expert” is the best qualifier for our particular market, which is the Enterprise; our customers are people like Microsoft, Qualcomm, Intuit, IBM, and Adobe. Our customers are less interested in “lowest cost” or “simplest installation” (even though our installation is simple). If my opinion is true, I’ve removed the single best product-positioning choice from competition, and they’ll have to find a less desirable, lower-percentage path.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/limiting-options/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF