Startup identity & the sadness of a successful exit

At the peak, the only place to go is down

My fingers trembled as I fed page 34 of 72 into the fax machine, deftly pressing the head of each page into its creaky jaws one at a time so that this shitty cheap machine wouldn’t snag two pages at once, slantways, obscuring the precious scribblings adorning the footer of each page where it read: “Seller’s Initials: ______”.

This is what the last six years were all for. All the labor. All the risk. The brave face for the troops. The self-inflicted unflagging optimism despite little supporting evidence. All those sleepless nights worried about making payroll with a one-time revenue business model where every month you have to find new revenue from new customers. The 10,000 deliberate hours of becoming an expert in something. The experience you get just after you need it. The hard lessons you occasionally glean from experience. The inner doubt suppressed for the morale of the team. No salary followed by low salary. The “eat what we kill” mentality. The scrounging and scrabbling and begging and fighting the assholes for those morsels of revenue, those crumbs of validation.

It’s over. We did it. I did it. American dream? Check.

The 73rd page spat out confirming the successful transfer of the previous 72.

And then… sadness.

A profound sadness. Not depression—not hopeless or rudderless—but pure sadness, when your lungs sink into your belly, the punch-in-the-stomach of discovering your dog was hit by a car or that your dad is terminally ill.

“What the fuck?” I thought, “Why am I feeling this? I’m supposed to be feel… happy? I guess? Something other than this.”

In good company

Almost all startup founders experience a deep and prolonged sadness after selling their company, even when the sale is an outrageous success. Why?

The answer is important and fundamental for all startup founders, whether or not they intend to sell their company some day.

It is more than generic malaise. It is a fundamental disconnection from what it is to be a human being, to be yourself, to drive towards something. Combined with the guilt of success, or at least the knowledge that you can never complain about not knowing what to do with the kind of time and money that nearly everyone else on Earth can only dream of.

And so you have mental break-downs like Vinay Hiremath, who sold his company Loom for nearly a billion dollars, nearly dying in the Himalayas and driving away his girlfriend (Figure 1); Markus “Notch” Persson, creator of Minecraft, who melted down on Twitter after selling to Microsoft for more than two billion dollars, after he found himself directionless and socially distant from everyone he knew, from employees to friends to girlfriends (Figure 2). There are many other stories from less famous but no less valid entrepreneurs.

Figure 1: Loom founder on his blog, after selling for $975,000,000.

Figure 2: Minecraft founder on Twitter, after selling for $2,500,000,000.

And of course it’s not just entrepreneurs—it’s anyone who devotes their life and identity to a cause which then suddenly vanishes. The quintessential and well-studied case are Olympic athletes, where a single-minded drive to be the best in the world, starting young and therefore occupying most of their conscious lives, reaches a pinnacle in whatever Olympic games is their last, whether they’ve won gold or not. The individual stories come both from the most decorated athletes in their sport1 and from everyone else who is objectively world-class.2 Many studies3 show that these anecdotes are examples of the rule, not exceptions.

1 e.g. Michael Phelps, especially in the HBO documentary “Weight of Gold” (2020); Lindsey Vonn in her autobiography Rise: My Story (2022).

2 e.g. Allison Schmitt in swimming, McKayla Maroney in gymnastics, Gracie Gold in figure skating, all vocal about their struggles as part of their new journey as mental health advocates.

3 The British Journal of Sports Medicine, “Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement” ( 2019). The IOC’s own consensus statements include the “ post-Olympic blues”.

Commiseration helps us understand that it’s normal, but it doesn’t help us understand why it’s happening, and therefore what to do next. For that, we have to put our finger on what’s going on.

Identity

“I sell my artwork on Etsy. Want to see?”

—Barista at an Austin coffee shop

If you ask her, “Who are you?” She would answer: “I’m an artist.”

If you ask her, “What do you do for a living?” She would answer: “I’m a barista, but that’s just my day job. Want to see my artwork?”

Is she a barista because she pours coffee for money? Is she a driver because she drives a car to work? Is she a maid because she cleans her own apartment?

No, she’s an artist because that’s what she really is. “Barista” is one of many necessary means to the ends, where the “ends” are the basic human needs, followed by creating art, I guess with some Maslow layers in-between.

A startup founder lacks this distinction between personal identity and work identity, and this is the key to the “sale-blues” phenomenon and other behavior.

A startup is the founder’s personal identity. Startups are not something you do to make ends meet or a “necessary evil” en route to what you “really” want to do.

A startup is an obsession. You do it because you couldn’t stop yourself. Because when you were doing anything else, you were thinking about it. That is the mark of “who you are.” Interviewers ask me “Why did you decide to do a second and eventually a fourth startup?” And the answer is “For the same reason that I started the first one—because it’s in my DNA and I have to do it.”

What do you do in your spare time when you have a startup? What spare time? This is all your time. It’s not just the last thing you think about before falling a sleep, it’s the thing that won’t let you sleep. It’s the first thing that trickles into your brain in the morning like The Matrix patterns filling the void.

It’s why you can weather the painful thoughts like the ones whistling through my ears while I fed legalese into a rickety fax machine. You are consumed, this is your life, this is you. There’s no room for anything else.

When you sell your company, others are quick to throw jabs like “So, you sold your baby?” Which means: “You’re a sell-out.” (Or: “I’m jealous.” Or both.)

It’s less like selling your baby and more like selling your own identity. Now you have to find a new one.

If there is a new one.

And there’s no particular reason to think there will be. Which is part of the fear.

Speaking of babies, this all sounds a lot like “baby blues”—depression caused by elevated levels of the enzyme monoamine oxidase A—that 70% of women experience after giving birth. A third of those women will experience this for up to a year (postpartum depression).

It’s characterized as a feeling of loss and of mourning, which is seemingly at odds with the arrival of a new life which is just the opposite—gain and celebration. This intellectual dissonance creates secondary emotional effects, specifically the devastating belief that “I must be a bad mom for being sad that I have a new baby.”

Are the baby blues the same emotional effect as selling a company? Maybe not—I already don’t like saying “a startup is like a baby.” Besides, postpartum depression is triggered by the arrival of responsibility and, if you insist on the baby/startup analogy, selling your company is the departure of responsibility.

But one thing that definitely is the same is that “feeling of loss and mourning.” A piece of yourself has been eviscerated, irrevocably.

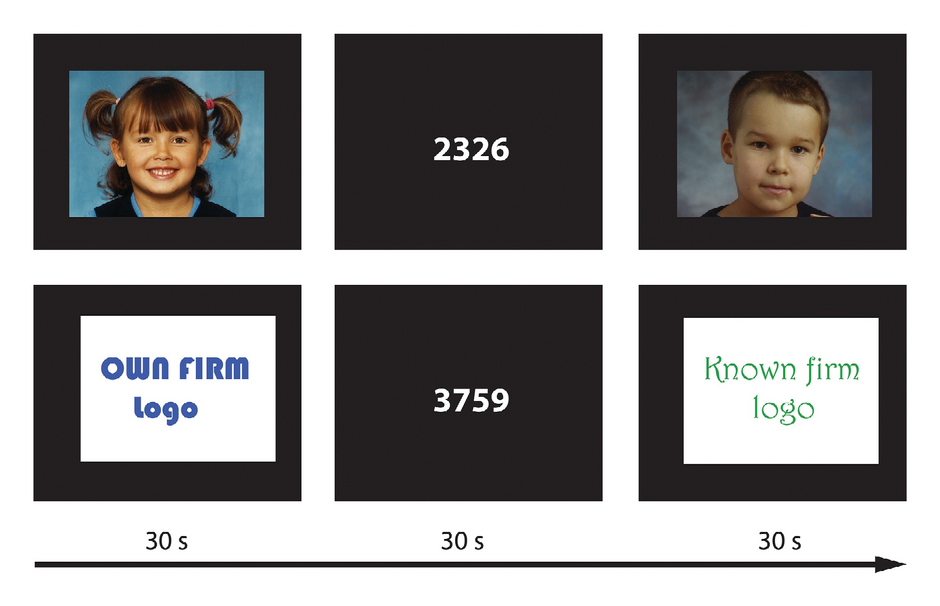

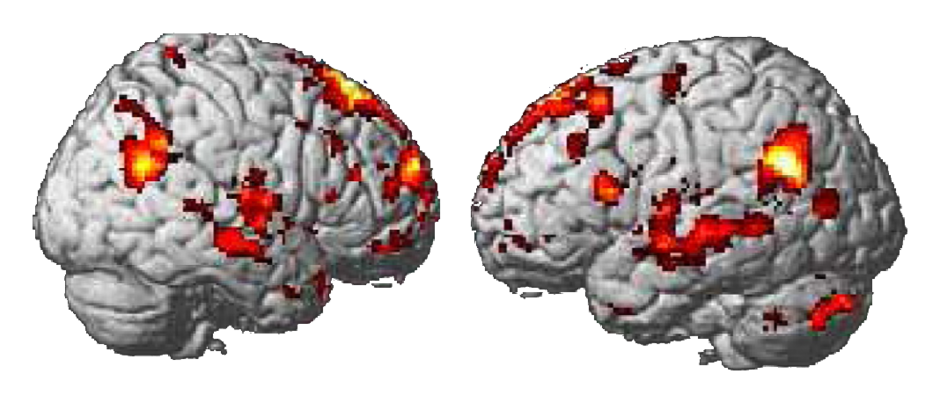

And, in fact, maybe it really is like your baby. In one study,4 researchers watched brain activity in people who were both entrepreneurs and parents. Comparing activity across neutral images, those of other children or company logos, or their own children and company logos (Figure 3), they found that the brain activity when exposed to their firm’s brands were similar to the activity when gazing at their own children, and of course both different from the other images (Figure 4). In short, our brains really do react to our companies the way they react to our children—the love, the attachment, the intensity, even the threats and risks and worries.

4 Marja-Liisa Halko, Tom Lahti, Kaisa Hytönen, Iiro P. Jääskeläinen, “Entrepreneurial and parental love—are they the same?” ( 2017)

Figure 3: Protocol showing images to parent-entrepreneurs — neutral, other children and brands, and their own children and brands.

Figure 4: The areas of the brain that light up when viewing your own children or your own brands, different from other images.

As we showed earlier, it’s not only a normal feeling, it’s by far the majority case. In a high-quality study from Columbia Business School, out of 22 entrepreneurs who sold their companies, every one of them experienced this effect. Some refocused the energy into the Next Thing (almost always new ventures), but most took years to find that thing which could replace not only the excitement but identity, and many still haven’t found that Next Thing at all. Many wished they could have their companies back; a few did buy them back.

Selling their companies forced them to answer a difficult question: If you could do anything, what would you do? What’s really important to you, as opposed to a job? What do you really want to be when you really grow up?

The problem is, the startup already was that thing! It’s a grinding, batshit-crazy, risky, irrational, epic adventure. You wouldn’t have done all that in the first place if that wasn’t already the thing you wanted to do. A startup is never the easiest career path.

Does this lead to the conclusion that selling a startup is the wrong choice much of the time?

No. And this is perhaps an ever sadder realization.

It’s an easier decision if you’re saying “I can’t wait to start the next thing” but perhaps you’re thinking “I don’t know what I’ll do with myself.” You must resist the urge to believe that getting millions of dollars will make you fulfilled, or happy. “Money doesn’t make you happy” is cliché because it’s true. You need to understand how to be fulfilled regardless.

But all that doesn’t mean selling is wrong.

Just like a bad relationship that has to be ended even though it will be painful, especially if you genuinely love the other person: Just because it’s painful doesn’t mean you don’t need to do it.

Building a company in year-one is completely different than building that company through year seven (when I left Smart Bear) or year fourteen (when I left WP Engine). The CEO’s job description changes over time, and so does the company, whether you sell it or not. Are you emotionally prepared for this as well?

Are you OK with innovation taking a back seat to developing scalable, mature processes? Are you OK releasing control in day-to-day operations to managers, and then releasing control of the managers to your executive team? Are you OK wresting yourself out of Visual Studio, out of Adwords, off the website, off the live chat, out of the sales calls, trusting your managers and not being that sort of meddling micro-manager boss that you yourself hate? Are you OK shouldering the burden of the livelihoods of dozens or thousands of families rather than “pulling 90 hour weeks” to push some code out the door with a co-founder, which now seems easy in comparison?

The fact is, successful startups grow up. They grow into businesses and mature into sustainability, risk-avoidance, HR law, strategic planning, executive meetings, and all that. The founder-CEO is still steering the ship but it’s a different sort of ship.

What to do? I wish the answer weren’t “it depends” or “every choice is a path of pain,” but often that’s what it is.

In my case, it changed over time. At Smart Bear I didn’t want to lead a huge company. I didn’t want to relinquish Eclipse and my ability to check in code. I didn’t want to manage managers or figure out what changes, strategies, hiring, products, marketing, and sales were needed to make $100M/year. So for me I sold at a good point: before I needed a C_O, but after the company was big enough to garner enough money to cross the Freedom Line.

Now at WP Engine, I have new ambitions and inclinations. I am now that CEO5 who manages managers, who sets vision and direction but not day to day operations, who worries about company culture but who doesn’t have SSH access to all the servers, and who is driving towards a company with products and a market and a team which we believe can indeed generate $100M/year.6

5 Editor’s note: Written in early 2013, later that year the wonderful Heather Brunner joined as our CEO, still leading the company 10 years later, as what I’ve since called a “late-joining founder.”

6 Editor’s note: It did, at hyper-growth velocity. Now, in 2023, our revenue is many times that figure.

That’s exciting to me. This is my new challenge. I will always love writing code and getting a company from $0 to $1M/year.

But, today, right now, for reasons unknown even to me, this is who I am.

I went to find the pot of gold

That’s waiting where the rainbow ends.

I searched and searched and searched and searched

And searched and searched, and then…

There it was, deep in the grass,

Under an old and twisty bough.

It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine at last…

What do I search for now?

—Shel Silverstein, Where the Sidewalk Ends

Editor’s note: I would later develop a personal framework for avoiding burn-out and staying with the company for the long haul. That story and system might help you if you’re struggling with this now!

https://longform.asmartbear.com/identity-selling-sadness/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF