Failure to face the truth

A primary blocker of progress, from our personal lives to our corporate strategies, is a

Failure to face the truth.

“The truth hurts.” Yeah, so we avoid it. The truth is hard to find if we’re not looking for it, and we’re not. Denial (when intentional) and rationalization (when unintentional) is our normal operating mode. Because we don’t realize this, it’s an immense, invisible barrier. Whether because we don’t like to admit we’re wrong (even to ourselves, in secret), or because it will be annoying or painful or career-altering for the truth to be said aloud, we avoid the truth.

Once you start seeing the pattern of “failure to face the truth,” you see it everywhere. In almost every meeting, someone is thinking something and not saying it, even though one of the best uses of a meeting is to unveil and discuss insights. In every strategy discussion, there’s a monster in the room no one will name, even though the point of strategy is to identify and then construct a battle plan against the monsters. Written plans and strategies are all optimism and confirmatory data, rather than crystalizing the scary challenges so that we can attack them together.

Those who break through this barrier are rewarded, as many famous books and frameworks point out. It’s fun to see this in action, because the examples are individually interesting, and because a totality of instances illuminates the pattern.

Radical Candor

“When you say ‘um’ every third word, it makes you sound stupid.” Not the feedback Kim Scott was hoping for after what she thought was a successful presentation to executives at Google. And it came from Sheryl Sandberg of all people. (Before she joined Facebook).

Now Scott knew, that Sandberg knew, that Scott wasn’t stupid. Therefore, it was obvious to her that this feedback was meant to help, not “obnoxious aggression” as Scott would later name the same straightforwardness when the motives are to belittle and hurt rather than to coach. And so Scott was grateful for being made to “face the truth.” In her words:

Why had nobody told me for 15 years? It was like I’d been walking through my whole career with a hunk of spinach between my teeth and nobody had had the courtesy to tell me it was there.

The truth is a courtesy; conversely, failure to face the truth is at least impolite, and at worst “ruinous” in Scott’s terminology, as when a manager withholds necessary feedback for fear of hurt feelings or being seen as unkind.

Scott is now famous for promulgating this philosophy of direct, honest, empathetic facing-of-the-truth in her book, Radical Candor. It starts with a foundation of personal trust—trust that the feedback-giver genuinely cares for the well-being of the feedback-receiver, and that it is given in the spirit of “facing the truth” and not in the spirit of domination or manipulation or other ill-intent that people in positions of power might visit upon those subject to that power.

We’re thankful when a coach admonishes us and shows us a better way; a coach that lied to you, even by omission, telling you everything is fine when it isn’t, would be a bad coach.

Five Dysfunctions of a Team

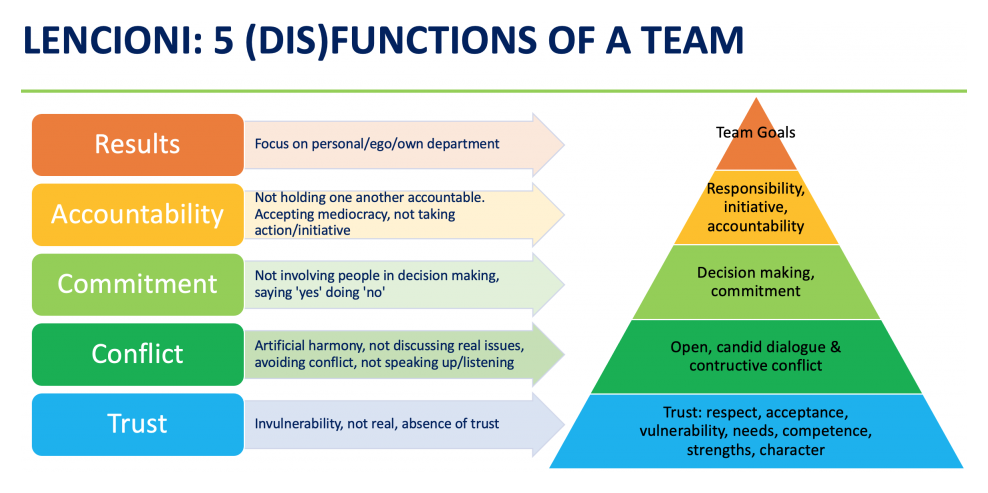

Possibly the most famous book on diagnosing problems in team dynamics and building high-functioning teams, Five Dysfunctions by Patrick Lencioni starts with the observation that great teams are built in layers, each requiring the next to be effective:

Figure 1

Exactly like Scott’s Radical Candor, it is critical that a team be capable of constructive conflict, “discussing the real issues,” facing the truth. That requires the team to first build trust, so that it is safe to have conflict.

“Failure to face the truth,” together, in the open, prevents teams from being great. We must have enough trust in each other to face the truth, together. If someone can’t handle that trust, maybe they’re not right for the group after all.

Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

In one of the seminal books defining “strategy,” Richard Rumelt lists common hallmarks of bad strategy. Each one is so common, you’ll shake your head and laugh (or cry, if you’re guilty of these sins):

• Fluff. Fluff is a form of gibberish masquerading as strategic concepts or arguments. It uses [non-specific or] esoteric concepts to create the illusion of high-level thinking.

• Failure to face the challenge. Bad strategy fails to recognize or define the challenge. When you cannot define the challenge, you cannot evaluate a strategy or improve it.

• Mistaking goals for strategy. Many bad strategies are just statements of desire rather than plans for overcoming obstacles.

• Bad strategic objectives. A strategic objective is set by a leader as a means to an end. Strategic objectives are “bad” when they fail to address critical issues or when they are impracticable.

—Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, p32

His phrase “Failure to face the challenge” is my inspiration for “Failure to face the truth.” Strategy must identify and then address the most important and difficult facts-of-the-matter of the market, competitive space, customers, product, and team.

It’s scary to say “Our market is shrinking,” but if it’s true, and you refuse to identify it, if you don’t write it down that crisply, if you don’t challenge the company to come up with alternatives for how to address it, if you don’t build a strategy that expressly attacks it head-on, then it will be fatal. Face the truth.

Lazy language belies a deeper failure

There are traces of “failure to face the truth” even in Rumelt’s other bullets. Fluffy language is a personal peeve of mine. In the benign case it is simple laziness—avoiding the work of crafting prose by filling the requisite space on the page with jargon and generic phrases. In the worst case, it belies the lack of having thoughts in the first place.

This problem is rampant in marketing and content-marketing, but sticking with the theme of strategy, it’s especially common in “vision” or “mission” statements, theoretically summarizing the company’s aspirations, but often just a non-specific blob that also applies to any other company in the space, e.g.

A leading provider of website development for businesses of all sizes.

Well, that was easy! Easy because it says almost nothing, and as a result, it’s wrong. Wrong because it doesn’t develop websites both for coffee farmers in Ethiopia and also for Tesla’s launch of their next vehicle (“all sizes”).

Perhaps it’s mere laziness; after all, the only words that communicate anything about what it is, is “website development.” Or perhaps the company refuses to “face the truth” of what it really does, and who it really serves, where it’s really strong but also weak, afraid to say “no” to any potential customer. What if, instead:

We are boutique artisans chosen by discerning businesses who demand the highest-quality, completely unique web experiences.

Sounds like a small company (“boutique”) who nevertheless charges a lot (also “boutique”), but delivers amazing work (“discerning” and “unique”). By saying “no” to people who don’t want that, you get to say “yes” to interesting projects at profitable rates, even beating out larger competitors who you can argue are just “factories that churn out the same website with different colors.” But only if you face the truth.

Confront the brutal facts

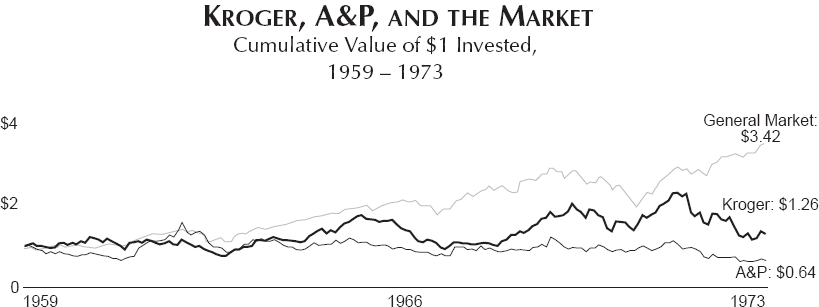

In Good to Great, one of the most-cited books on the formula (if such a thing exists) for successful businesses, Jim Collins frequently returns to the story of A&P and Kroger—two companies alike in dignity in fair 1960s America, where we lay our scene—yet Kroger catapulted past A&P because, in Collins’s words, only Kroger was willing to “confront the brutal facts.”

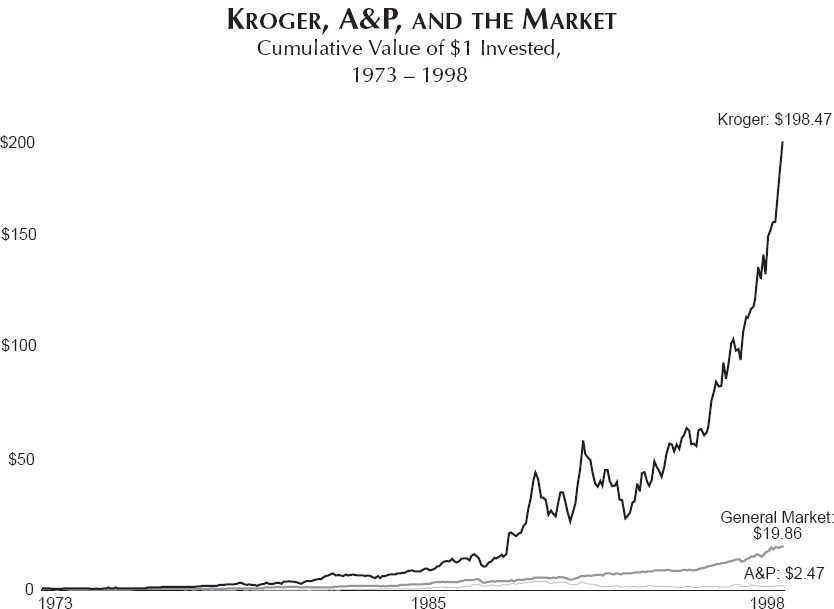

Kroger and A&P grew about the same for twenty years, both under-performing the broader market. Grocery stores are hard.

(Source: Good to Great)

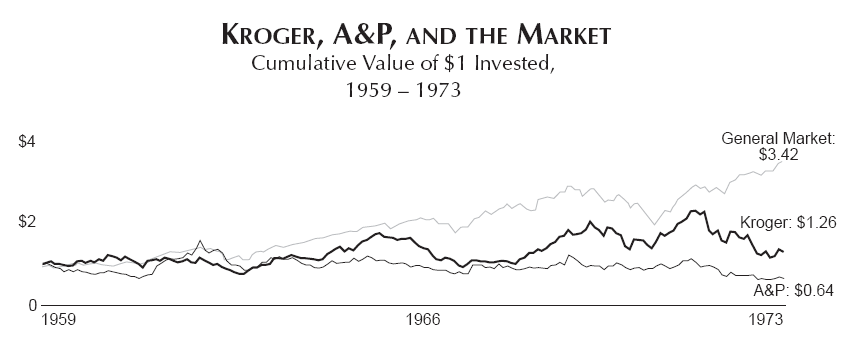

Kroger exploded with success after “confronting the brutal facts,” while A&P continued to falter.

(Source: Good to Great)

Collins tells a fantastic story, abridged here:

A&P stood as the largest retailing organization in the world and one of the largest corporations in the United States, at one point ranking behind only General Motors in sales. Kroger, in contrast, stood as an unspectacular grocery chain, less than half the size of A&P.

…

A&P had a perfect model for the first half of the twentieth century … cheap, plentiful groceries sold in utilitarian stores. But in the affluent second half of the twentieth century, Americans changed. They wanted … bigger stores, … fresh-baked bread, flowers, cold medicines, forty-five choices of cereal, and ten types of milk. … and they wanted to do their banking and get their annual flu shots. In short, they no longer wanted grocery stories. They wanted super-stores.

…

Here’s what’s interesting: Both Kroger and A&P were old companies heading into the 1970s [Kroger 82, A&P 111]; both companies had nearly all their assets investing in traditional grocery stores; both had strongholds outside of the major growth areas of the United States; and both companies had knowledge of how the world around them was changing. Yet one of these companies confronted the brutal facts of reality head-on and completely changed its entire system in response; the other stuck its head in the sand.

Collins goes on to detail this last sentence—how both companies were fully aware of these changes, A&P even opening a test store under a different name, which was a “super-store” that didn’t even sell A&P items, which outperformed their standard stores. Not wanting to face those facts, they shuttered the test store and went back to business-as-usual. Meanwhile, Kroger made the same experiments, found the same results, and decided to pivot the entire company to become the modern-day supermarket.

A&P saw the truth, but failed to face the truth. Whether it’s Jim Collins analyzing dozens of companies or Rumelt with his experience with dozens of strategies, the pattern is the same: Face the truth, or be killed by it.

When it’s hard, we avoid it

It seems obvious that avoiding the truth would lead to bad outcomes, so why do we do it? Because it’s hard. It’s not the only obvious thing in our lives that we avoid, solely because it’s hard. Diet? Exercise? Giving feedback? Working on our relationships?

It’s hard to tell the truth to someone’s face. It’s hard to realize that your industry has completely shifted, and it’s really hard to say that out loud in front of the whole company. It’s hard to say “no” to a customer when you have bills to pay, and it’s hard to make a major strategic choice, because what if you’re wrong?

That’s a good explanation for failure to face the truth, but it’s not a good reason.

Face the truth.

Go ahead. Faith will follow.

—Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert, encouraging early practitioners of calculus, even though rigorous proofs of its legitimacy were still a hundred years away.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/failure-to-face-the-truth/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF