When being an “expert” is harmful

In an all-hands discussion at Austin Texas’s premier startup incubator Capital Factory, one of the founders started a question with a well-worn preamble:

“A bunch of mentors told me the same thing about pricing, but I’m telling you, they’re wrong. I know our industry, I know how our customers think, and in our industry …”

What followed was well-reasoned and sensible. Since none of the mentors have specific expertise in the industry in question, it was impossible to argue.

So rather than argue, I just asked:

“OK, so when you talked to the last dozen potential customers and proposed the pricing scheme you just described, you’re telling me they all said, ‘Heck yes’?”

“Well, I didn’t actually ask them, no.”

“Why not?”

“Because I know what they’re going to say.”

“Great! So, next week you’re going to a convention where you’ll talk to dozens of new potential customers. Do me a favor—humor me!—and include your pricing scheme in the pitch. I’m sure you’re right and they’ll be thrilled; since you’re so certain, it will be easy. In fact, it will strengthen your pitch because it will match their expectations and therefore mitigate any worry that you don’t ‘get it.’”

“OK, I will!”

I could already see the self-satisfaction on her face. She knew she’d have a great “I told you so” moment next week, and in fact I was equally sure she’d have that moment! She is the expert, I’m not. Case closed.

Of course (you know what’s coming), it turns out she was wrong. And whenever an assumption is kicked out from under you, that’s when you learn the most.

The following week she sent me this email. The conversation above was my best recollection, but the following is a direct quote (with my emphasis):

Ever since accidentally stumbling upon lean startup 1+ years ago, I’ve struggled to implement the principles correctly. Somehow my version of “lean” customer discovery involved hour long phone calls, relationship-building networking meetings, vague answers to improperly formulated questions…

In the past week of quick phone calls to vendors, I’ve learned more about this market than I did in the past year.1 I also got a good feel for when I no longer needed to do further discovery.

1 If you similarly need guidance on how to do customer discovery better, here’s my method.

We’re all plagued by this defect of human nature—thinking we know more than we do—which then causes us to miss opportunities to actually learn something. I still struggle—in every customer call I have to consciously restrain myself from pitching, instead asking questions, genuinely trying to understand what they mean instead of mapping their words onto what I want them to say.

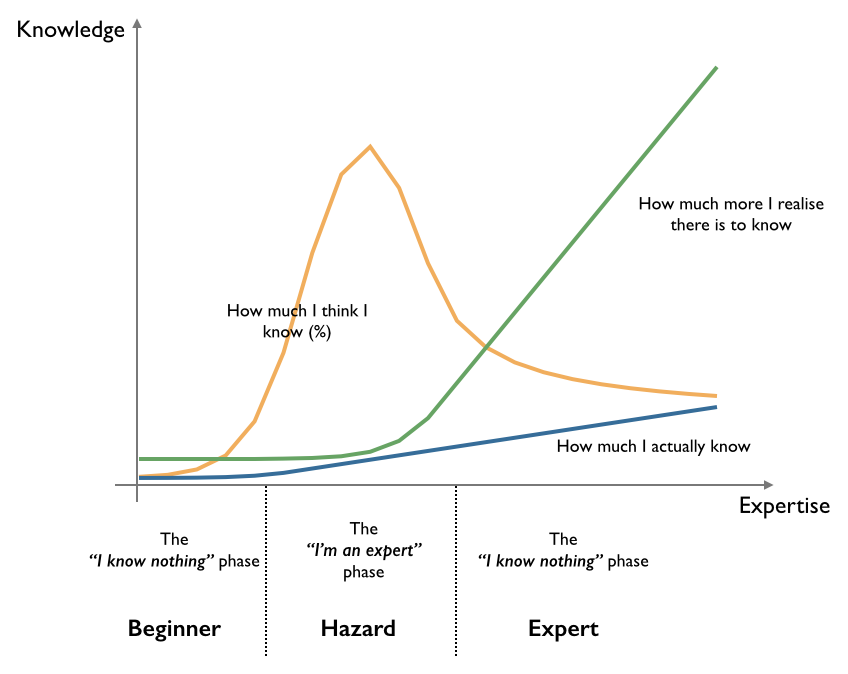

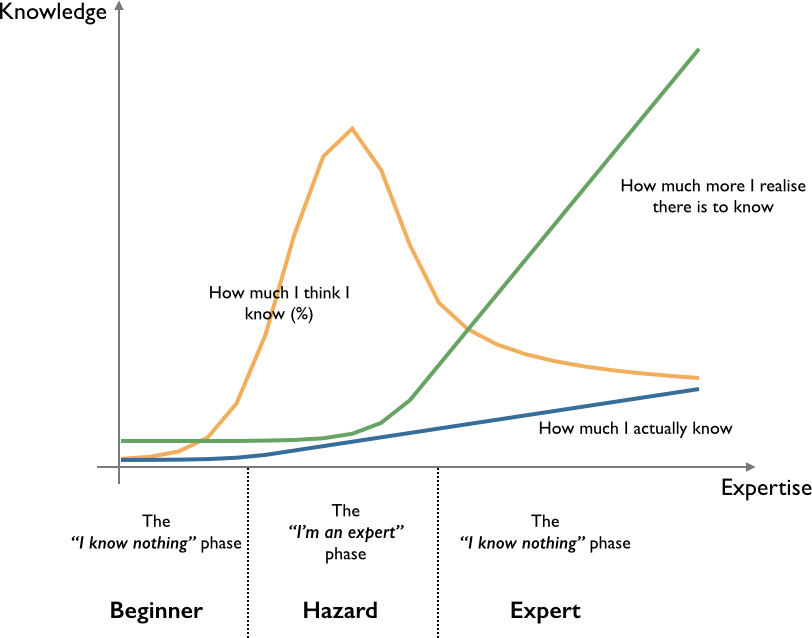

“P.S. Just in case, the above is meant to be a joke and a social commentary on the hubris of self declared experts. It’s based upon precisely nothing. Just because someone draws a graph, doesn’t make it real.” —Simon Wardley, 2008

The worst is when you’re an “expert” because then you’re even less likely to challenge your assumptions.

As an “expert” you’ve devised your own laws about what makes your market different from other markets, and what makes your company unique. Even with prior experience, this knowledge based largely on feeling, not fact.

When I say this to “experts,” their first reaction is (of course) defensive. “But I have 15 years of experience selling into the financial services sector; I know what makes them tick.” Shoot, I used this excuse myself recently: “I built a company and forged dozens of customer relationships in the software development tools sector; I know exactly how to sell into that market.”

This is wrong for a number of reasons.

First, markets change rapidly. You can’t rely on five-year-old information about your potential customers—even the stodgy big-company ones but especially the mass-market consumer ones.

Non-technical people now employ technology (iPhones, Facebook). Industries built around control of process and information are now out of control (real estate, book publishing). Methods of reaching consumers change every year (compare SEO or AdWords strategies from 2003 and 2010).2 Expectations of what software should do, or what it should integrate with, or whether it’s OK for data to live on your laptop or someone else’s server, or whether it needs to be accessible from a cellphone—it’s all changing, all the time.

2 Editor’s Note from 2024: In 2003 with Smart Bear I was often the only bidder for a keyword, and paid $0.05/click, and therefore I was able to use AdWords to bootstrap that company. By 2010, when I started WP Engine, AdWords were too expensive to start with anything but long-tail phrases, and only become a staple of marketing when we could afford it, and even then was always one of the lowest-ROI marketing activities. Today in 2024, most bootstrappers say it’s prohibitively expensive to use advertisement at all; this might partly be a reflection of their lack of sophistication in paid-advertising, but also the ROI of AdWords has continued to worsen.

Ironically your 10-15 years of experience “in the field” might be clouding your judgment. Some of that experience is invaluable—so much so that it’s an unfair advantage and something you really should leverage. But your outmoded ideas prevent you from addressing the market as it is today, allowing a competitor to beat you with innovative advances they achieve exactly because they’re not shackled by old ideas.

Another way your experience can hamper you is that selling different products into the same industry is different.

For example, I talked to an entrepreneur with years of experience selling a standard medical device to doctors. He has an idea for a new software package for managing an expensive, time-consuming aspect of practice-management. Of course his Rolodex gives him an lovely advantage—he can bounce ideas off potential customers and line up ten alpha testers before writing a line of code.

But he hadn’t done that. He told me that he’s been selling to doctors for years. I asked whether it was OK to install new software on their computer; he didn’t know because he was selling hardware before. I asked whether it was OK to depend on an internet connection inside a secured hospital; he said “probably” but he’d never asked. I wondered what they would pay for this software; he said they paid a lot for this medical device so it should be easy to get lots of money for this software. I doubted that the budget for front-office software bears any relation to the budget for devices; he hadn’t thought of that. I asked how many people had agreed they actually wanted this particular software, even for free, and he said zero, so far. But that didn’t worry him.

Your knowledge of one slice of a market doesn’t automatically set you up for other slices. You’re not starting from scratch, but you have to have an attitude of re-learning, of questioning everything.

Of course if you can fuse your special knowledge with an open mind, that could very well be an unbeatable combination.

But you have to set your ego aside and actively force yourself to explore anew with a “child-like” mind. Use that Rolodex to set up meetings and sales calls, but don’t assume you know what they’re going to say. Use that experience to come up with plausible theories, not to make decisions.

It won’t happen unless you force yourself to do it.

After all, you’re the expert.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/expert-harmful/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF