Not disruptive, and proud of it

The phrase “paradigm shift” died during the 2000s tech-bubble along with “portal” and “think outside the box,” and yet the underlying concept never died. For the past ten years it’s been called “being disruptive.”

When I get pitched—usually by someone raising money—that they “have something disruptive,” a little part of me dies. You should be worrying about making something useful and delightful, not about how “disruptive” you can be.

Disruption is occasionally a consequence of innovation, but when it becomes your primary purpose, you’ve lost sight of why you should be doing any of this in the first place.

“Disruptive” is the in-vogue word for the opposite of “incremental improvement.” A disruptive product causes such a large market shift that entire companies collapse (the “dinosaurs” who don’t “get it”) and new markets appear.

Disruptive is fascinating, disruptive changes the world, disruptive makes us think. Disruptive also sometimes generates billions of dollars, which is why venture capitalists have always loved it and always will (and they’re not wrong, given their goals).

But disruptive is rare and usually expensive. It’s hard to think of disruptive technologies or products that didn’t require hundreds millions or even billions of dollars of investment, spending ahead of revenue. Most of us don’t have access to those resources, and many of us don’t care, because we’d rather work on an idea we actually understand and can build ourselves, an idea that might make us a living, that people want and need, maybe even something people love.

There’s nothing wrong with incremental improvement. What’s wrong with doing something interesting, useful, new, but not transcendental? What’s wrong with taking a known problem in a known market and just doing it better or with a fresh, unique perspective? Do you have you create a new market and turn everyone’s assumptions upside down to be successful? Should you?

I’m not so sure. This is the argument against disruption.

It’s hard to explain the benefits of disruption

Have you tried to explain Twitter someone?1 Not the “140 characters” part—the part about why it’s a fundamental shift in how you meet and interact with people?

1 Editor’s Note: This was written in 2010, when Twitter was still relatively new. In retrospect, the point was correct—the vast majority of people who eventually got obsessed with social media, didn’t get obsessed with Twitter.

Hasn’t the listener always responded by saying, “I don’t need to know what everyone had for lunch. Who cares? What’s next, ‘I’m taking a dump?’” They don’t get it, right? But it’s hard to explain.

There are ways to elucidate the utility of Twitter, but even the good ones are lengthy and require that listeners have patience and open minds—two attributes in short supply.

“It’s hard to explain” means it’s a terrible sales pitch. “You just need to try it” and “trust me” don’t cut it. That may be OK for Twitter—today—but what about the 100 other social-networking-slash-link-sharing networks that didn’t survive? Ask them about selling intangible benefits.

People don’t want to be disrupted.

If you’re reading this you’re probably more open to new ideas and new products than most, because you’re inventing a new product, starting a company, or you’re just ruffled because I’m pissing on “disruptive” and you’re looking for nit-picky things to argue with me about. (Hi Hackernews comment section!)

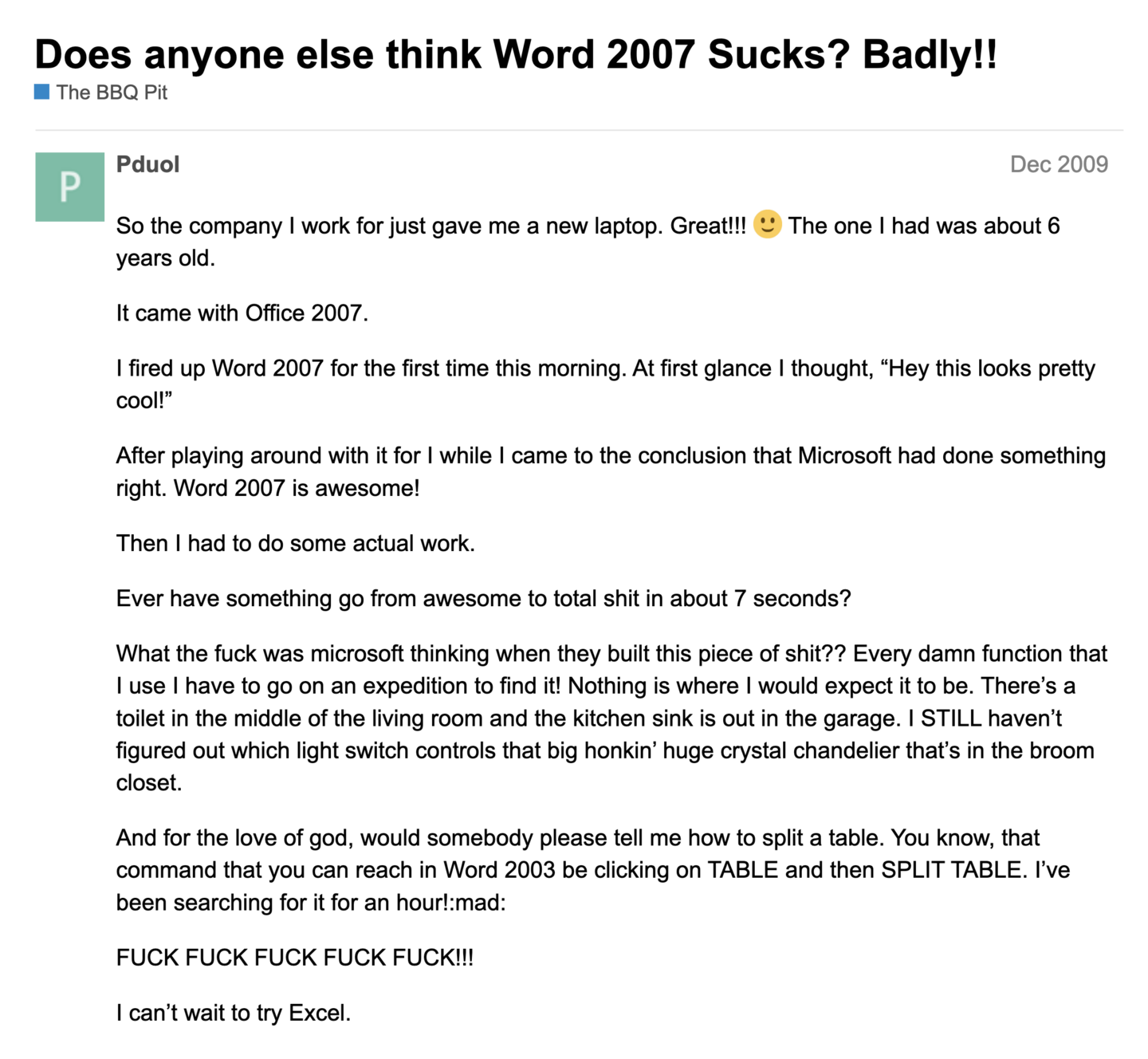

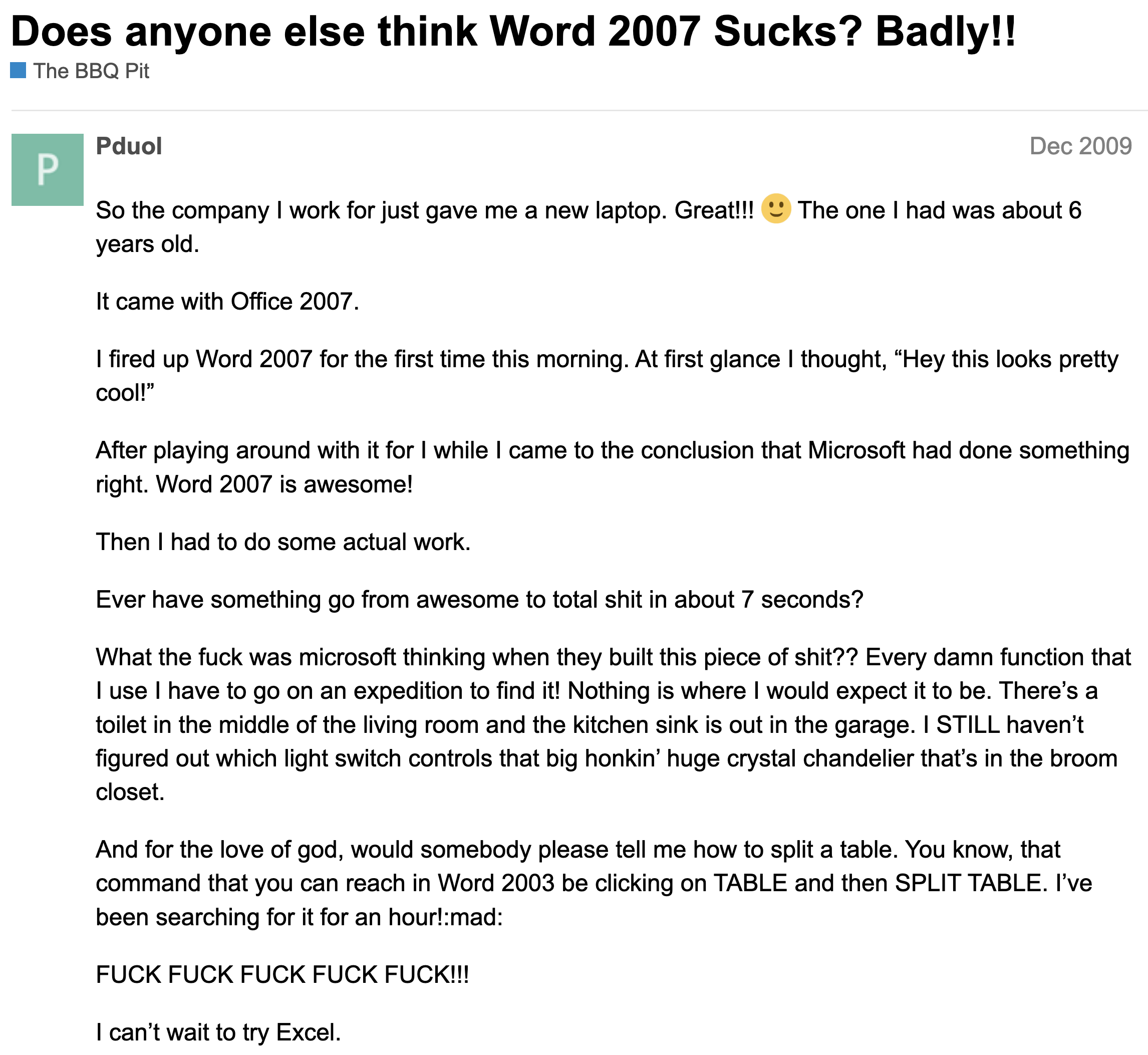

But most people are creatures of habit. They don’t want their lives turned upside down. They launch into a tirade of obscenities if you just rearrange their toolbar. When they hear about a new social media craze they cringe in agony, desperately hoping it’s a passing fad and not another new goddamn thing they’ll be aimlessly paddling around in for the next decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Change is hard, so a person has to be experiencing real pain to want to change. Selling a point-solution for a point-problem is easier than getting people to change how they live their lives. Identifying specific pain points and explaining how your software addresses those is easier than trying to tap into a general malaise and promising a better world.

Technology we now consider “disruptive” often wasn’t conceived that way.

Google was something like the 11th major search engine, not the first. Their technology proved superior, but “a better search engine” was hardly a new idea. In retrospect we say that Google transformed how people find information, and further, how advertising works on the internet.

Disruptive in hindsight, sure, but the genesis was just “better” than the 10 search engines that came before. ( Or 18.)

Scott Berkun gives several other examples in a recent BusinessWeek article.2 He highlights the iPod—an awesome device, but not the first of its kind. Rather, there were a bunch of crappy devices that sold well enough to prove there was a market, but no clear winners. Here an innovation in design alone was enough to win the market. Not inventing new markets, not innovative features, not even improving on existing features like sound quality or battery life—just a better design, unconcerned about “disrupting” everything else.

2 It has since been taken down; the perils of writing for decades on the internet.

Setting your sights on being disruptive isn’t how quality, sustainable companies are built. Disruption, like expertise, is a side-effect of great success, not a goal unto itself.

The disruptors often don’t make the money.

The construction of high-speed internet fiber backbones and extravagant data centers fundamentally changed how business is conducted world-wide both between businesses and consumers, but many of the companies who built that system went bankrupt during the 2000 tech bubble, and those who managed to survive have still not recovered the cost of that infrastructure. They were the disruptors, but they didn’t profit from the disruption.

Disruptive technology often comes from research groups commissioned to produce innovative ideas but unable to capitalize on them. Xerox PARC invented the fax machine, the mouse, Ethernet, laser printers, and the concept of a “windowing” user interface, but made no money on the inventions. AT&T Bell Labs invented Unix, the C programming language, wireless Ethernet, and the laser, but made no money on the inventions.

Is it because disruptors are “before their time,” able to create but not able to hold out long enough for others to appreciate the innovation? Is it because innovation and business sense are decoupled? Is it because “version 1” of anything is inferior to “version 3,” and by the time the innovator makes it to version 2 there are new competitors—competitors who don’t bear the expense of having invented version 1, who have silently observed the failures of version 1, and can now jump right to version 3?

“Why” is an interesting question, but the bottom line is clear: Disruption is often unprofitable.

Simple, modest goals are most likely to succeed and make us happy.

It’s not “aiming low” to attempt modest success.

It’s not failure if you “just” make a nice living for yourself. Changing the world is noble, but you’re more likely to change it if you don’t try to change everything at once.

I made millions of dollars at Smart Bear with a product that took an existing practice (peer code review) and solved five specific pain points (annoyances and time-wasters). Sure it wasn’t worth a hundred million dollars,3 and it didn’t turn anyone’s world inside-out, but it enjoys a nice place in the world and it is incredibly fulfilling to see people happier to do their jobs with our product than without it.

3 Ten years after this was written, Smart Bear continued to grow and acquired other profitable, bootstrapped companies in the software-quality space, eventually being sold for nearly $2B. None of the products were “disruptive,” but all were well-executed.

Had I tried to fundamentally change how everyone writes software, I’m sure I would have failed.

I made less money personally at ITWatchDogs, but the company was profitable and sold for millions of dollars. We took a simple problem (when server rooms get hot, the gear fails) and provided a simple solution (thermometer with a web page that emails/pages you if it’s too hot). There were many competitors, both huge (APC with $1.5 billion market cap), mid-sized (NetBotz with millions in revenue and funding), and small ($2M/year operations like us). We had something unique—an inexpensive product that still had 80% of the features of the competitors—but nothing disruptive.

Had we tried to fundamentally change how IT departments monitor server rooms, I’m sure we would have failed.

There’s nothing wrong with modesty. Modest in what you consider “success,” and modest in what you’re trying to achieve every day:

My daughter convinced me that insisting something be Deeply Meaningful With Purpose can sometimes suck the joy from it.

—Kathy Sierra

Of course it’s wonderful that disruptive products exist, improving life in quantum leaps. And it’s not wrong to pursue such things!

But neither is it wrong to have more modest goals, and modest goals are much more likely to be achieved.

Editor’s Note from 2024: In the fifteen years since this was written, I started another company WP Engine, which is still growing and profitable at hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, powering 2.5% of the largest websites in the world. It still wasn’t because we wanted to “fundamentally change how website are created,” but rather we saw how to dramatically improve something that people were already doing by the millions: Running WordPress sites. More of its origin story is here.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/disruptive/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF