Our unhealthy fixation with emulating #1

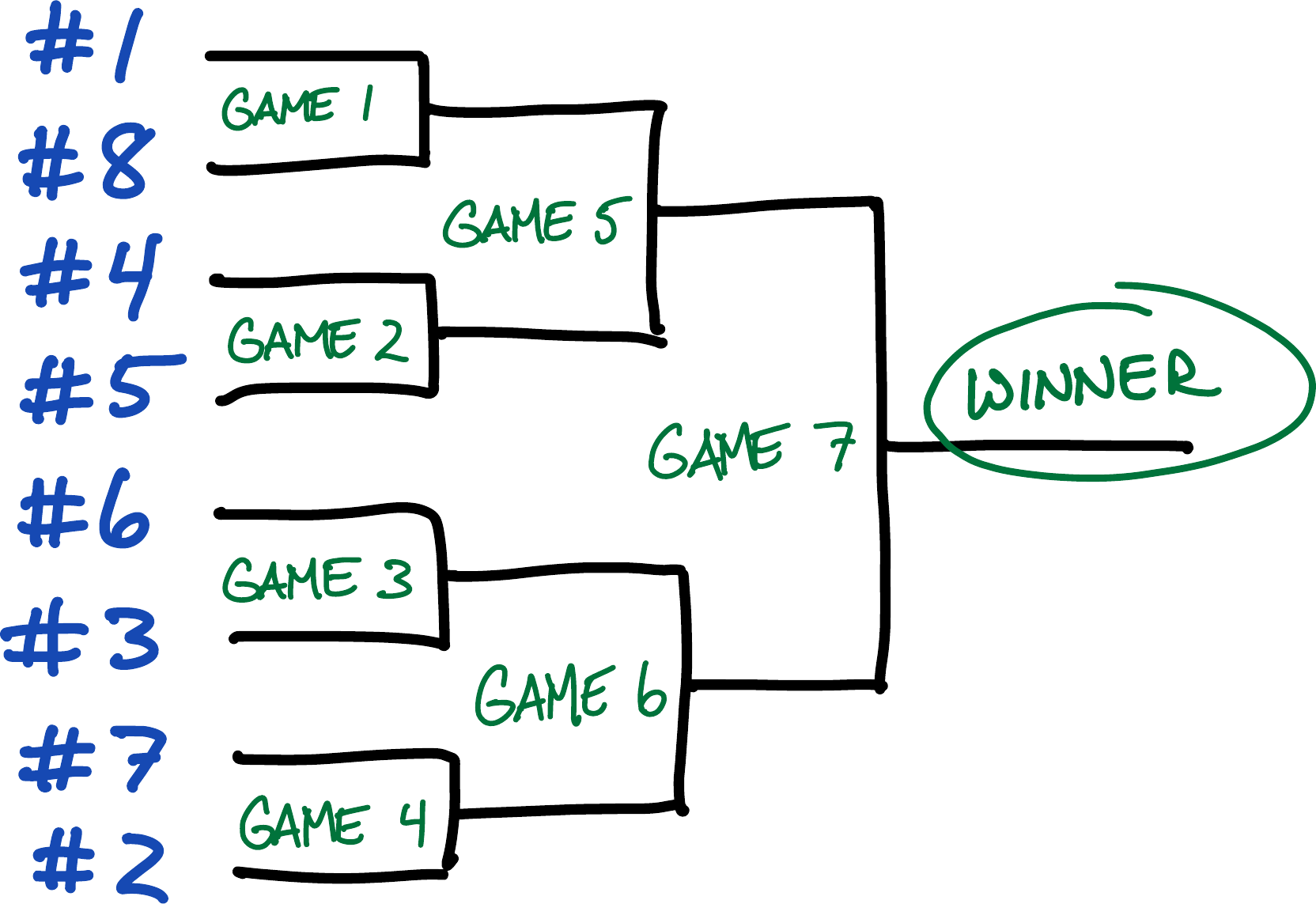

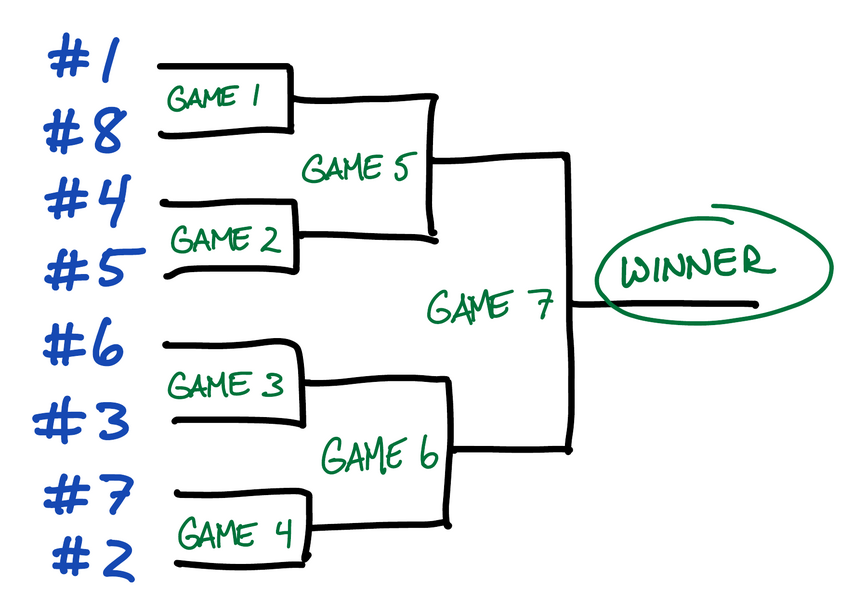

Many sporting contests culminate in a single-elimination tournament, where each match produces a winner who continues on, and a loser who goes home:

Figure 1

At the end, only one contender will be undefeated, earning them the crown of “undisputed champion”.

But this neither as clear nor as fair as it seems (as any sports fan will agree, as they start rattling off examples). Being “undefeated” is merely a result of the system itself, not necessarily proof that the winner is in fact better than other top contenders.

To see why, consider this extreme variant: The “sporting contest” is actually just a coin flip. The tournament will work the same, with half the teams losing in the first round, half of those remaining exit in the second, and so forth, until the final match where one team will be undefeated.

Of course in this example the team earning the title of “number one” is random because the contest is random, but the distribution of how many teams made it to each stage and the fact that exactly one went undefeated is dictated by the tournament system, regardless of how random each contest is.

The outcome of most sporting events are a combination of skill and luck in unknowable proportions. This is why sports are exciting and suspenseful; on any given day a lesser-skilled underdog can win (whether by might or by luck). You could mitigate the luck factor by replaying a match a number of times and declare win/

Business is also a combination of skill and luck in unknowable proportions, and it’s also clear that some tournament system of markets and economics determines the distribution of results, and that it’s an experiment we can run only once. The very fact that long tail distributions are common in many industries indicates that there are systematic effects outside the typical “luck versus skill” debate.

We tend to fixate on whoever is #1, in business as with sports, tacitly assuming that the contest is mostly skill and therefore the tournament has selected the rightful leader. But I’m not so sure we know the skill/luck proportion. I’m not sure we can assume the contest (marketing, sales, product) and tournament (the marketplace) picks #1 based on a repeatable, codify-able law. Same with #2 or anyone else.

Does the winner of a pitch contest have a better shot at their business than #7 who learned from the experience and is now redoubling his efforts?

Does McDonald’s have all the answers or does the #12 largest fast-food chain in the world also have something to teach us?

Isn’t the #4253 largest company in the world still a success story, perhaps with new lessons and perspectives?

If we reset the clock and the Google guys published their PageRank paper at MIT instead of Stanford, and didn’t get plugged into the Silicon Valley system, would Google have existed?

How do we know which decisions were important, that actually caused success?

Alright, so what? When does this matter?

When someone insists you need to be “more like Google,” consider that perhaps it’s the only thing they know to compare to.

When someone insists you need to be “more like 37signals,” consider that almost no successful companies are like 37signals.

When someone insists you need to be “more like Apple,” consider that they probably have no idea what really goes on inside Apple, or whether they’re anything like you. Also, do they mean “Apple, today” or “Apple when they were 3 years old, like you, and doing hardware with the mindset of the late 1970s”?

No. More interesting is when someone suggests that you remind them of this other little company you’ve never heard of, but when you visit their website and try their product you realize it’s resonating with you, that this feels like a finer, more mature version of yourself, that you’re getting reinvigorated about your own business not because of their top-line revenue or celebrity status but because they’re inspiring you to become a better version of what you already are.

It’s fine to muse about being #1, but let’s not all strive to become just like #1.

https://longform.asmartbear.com/copy-number-one/

© 2007-2026 Jason Cohen

@asmartbear

@asmartbear ePub (Kindle)

ePub (Kindle)

Printable PDF

Printable PDF